On the surface, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) and ostriches (Struthio sp.) are similar birds. Both species have a similar body plan – giant, flightless, and equipped for running.

With these features in mind, it is no wonder that emus and ostriches belong to the same group of primitive birds called ratites.

However, when you look at the taxonomy, you’ll find that they are not that closely related – not sharing the same order or family, let alone a genus.

That is because there are some stark differences between these birds, despite all the superficial similarities:

- Ostriches live in Africa, while the emu is found in Australia.

- Ostriches are larger than emus, and their eggs are the largest of all birds.

- They differ in many physical features, as well as coloration and behavior.

- There are two species of ostriches – Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus) and Somali Ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes), and only one species of emu.

Want to know more about the differences between ostriches and emus? Read on and find out!

To keep things easier to follow, the information on ostriches will relate to the common ostrich unless stated otherwise – the differences between the two species are subtle anyway.

On this page

Body & Shape

Although the basic body plan of emu and ostrich is similar, many traits make these two birds distinct. It’s important to remember that both are flightless birds.

Ostriches are easy to recognize thanks to their necks and sheer height. Photograph © Laurent de Walick

The ostrich is a large flightless bird and heavier than the emu. In fact, the ostrich is the largest living bird, up to 9 feet tall and 330 pounds heavy, while the emu is the second largest bird species in existence—5 to 6 feet tall.

Wing Differences

Although they can’t fly, ostriches have long, visible wings they use for temperature regulation, courtship displays, and shielding their chicks. There is a slight reduction in bone structure when compared with flying birds, but still – the large wings of ostriches are well-developed and have a function.

On the other hand (or should we say “wing”?), emus have wings that are stunted and almost invisible unless uncovered. Also, they don’t have any known function.

Image credit Nature Communications

Feet differences

Emus and ostriches differ regarding the number of digits on their feet. Emus have three toes on their feet. Meanwhile, ostriches have only two toes. The toes of both species are equipped with quite sharp claws.

Feather differences

Ostrich feathers have a unique structure. They lack special tiny hooks that make feather segments interlock. Consequently, the feathers are soft and extra fluffy. The airy design made them a popular ornament in the past, landing the ostrich nearly on the brink of extinction due to overhunting.

Also, ostrich feathers are not waterproof and can get soaked during the rain. Still, the fluffiness helps the bird keep cool.

Emus have a distinctive shaggy plumage, which can look like fur. Photograph © gorfor

Emus also have a specific feather structure but in another way. Unique for the emu, many of its feathers feature double shafts or rachis. A single shaft splits in two and forms “siamese twin” feathers.

Both ends of the rachis are of the same length, but the texture of the feather varies from the beginning to the end. The segment near the skin is fluffy, and the distant end is pointy, almost grass-like.

Related: Are birds mammals?

Emu’s feathers also lack hooks that would make them interlock. This feather structure allows emus to retain water after a bath, which helps them avoid dehydration in their dry native habitat.

Neck differences

Although both species have long necks, the ostrich’s neck is longer. About half of the ostrich’s impressive total length is its neck!

Emu’s neck is bluish and covered with feathers to a greater extent. The Common ostrich’s neck is pinkish-skin colored, covered only with thin, hair-like growth. However, the male Somalian ostrich has bluish neck skin.

Color and Sexual Dimorphism

In the emu world, males and females are no different regarding their looks, except that emu females are (unusually) slightly larger. Feathers of both sexes are black when they first appear and after molting. However, the sun fades them in time, giving emus their characteristic shabby, “highlighted” brown feathers.

Male and female ostriches look drastically different. Photograph © Regina Hart

With ostriches, it’s a whole other story – there is a stark difference in coloration. Males have black plumage with broad white feathers edging the wings and the tail. Females are more or less evenly dull brown.

The bills are also colored differently. In emus, both sexes have black bills. In ostriches, the male has a pinkish, while the females have a light brown beak.

Size

As mentioned in the previous section, the ostrich is the largest living bird. Male ostriches typically measure 6.9 to 9 feet in height. Female ostriches – the smaller of the two sexes – reach a height of 5.7 to 6.2 feet.

Interestingly, almost half of the ostrich’s height is its neck. As if that wasn’t enough, the ostrich is also the heaviest living bird. Male ostriches can weigh 220 to 287 pounds. Female ostriches’ weight ranges from 198 to 242 pounds.

The available data on ostrich height and weight can vary, but their 1st place is undisputed. According to some sources, males can reach the weight of 330 lb!

On the other hand, the emu is smaller – the biggest individuals get to be “only 5 to 6 feet tall. Still, it is the second-largest living bird, right after the ostrich – a sliver-medallist, still a good result.

Speed

Ostrich is the fastest runner in the avian world and the fastest bipedal (two-legged) animal. Scientists have witnessed ostriches achieving a continuous run of 30-37 mph and shorter sprints up to 43 mph. Also, they can cover more than 10 feet in a single stride!

Ostrich run is so powerful due to the long, muscular legs that act as springs and are superb at shock absorption.

Although it has a similar leg anatomy and is a great runner, the emu is slightly slower than the ostrich. Its top speeds are around 31 mph, with a stride of a bit below 10 feet. Although slower, this speed allows emus to outrun almost any danger. Interestingly, their legs are also helpful for swimming!

Lifespan

Ostriches are very long-lived birds. Their lifespan in the wilderness is 30 to 40 years, but in captivity, a healthy ostrich can age well into its 50s, 60s, or even more. Some sources claim that they can live to be over 70, which puts this stunning species on the list of longest-living birds.

The lifespan of an emu is significantly shorter – 5 to 10 years in their natural environment due to harsh conditions. Wild emus are frequently exposed to droughts and related dehydration and starvation. However, when spared these stressors in captivity and provided with good care, they can live up to 20 years.

Emu vs. Ostrich Behavior

Ostriches and emus live in a similar habitat – flat, dry, semi-desert areas, which explains some similar adaptations – both birds are diurnal, forage for food over great distances, and can outrun almost any threat.

Also, both birds can defend themselves with nasty, seriously dangerous kicks delivered by their powerful legs. Still, many of their behaviors are not even similar.

Ostrich behavior

Ostriches form groups, usually consisting of a dominant male with several females, one of whom is also dominant; there is a notable pecking order.

The average ostrich flock numbers about ten individuals or less but can occasionally grow to 100 or more birds. However, sometimes ostriches are seen in single pairs, and lone males can be seen during the breeding season.

The point of ostrich flocks is that many birds can spot dangers easier than one or just a few birds.

And in case you’ve been wondering – ostriches do not bury their heads in the sand. The myth probably stems from their defensive behavior when they lie low and press their necks against the ground in an attempt to be invisible (nice try for a bird 9 feet tall!).

Emu behavior

Unlike ostriches, emus are primarily solitary. However, they become social when being in numbers is an advantage. A typical example is the search for new food sources when large groups form and migrate together. Also, they gather for mating and nest sharing.

Emus are also well-adapted for swimming, propelled again by their muscular legs. They also take any opportunity to swim and soak their feathers in the water – a precious resource in the desert environment.

Although Ratities are not considered particularly intelligent due to their small brains, emus are very curious and can even seem playful. A typical example of emu play, displayed in captivity in particular, is pecking at other animals and running away just for the sake of it.

Diet

Elemental diets of ostriches and emus are reasonably similar. Both diets mostly consist of plant matter – primarily seeds, but also fruits, shoots, and roots – with an occasional insect or small vertebrates on the side. Although ostriches are technically omnivores, they do mainly eat plants but occasionally eat small animals, insects, or reptiles.

Similarly, both birds consume hard, indigestible items such as pebbles to help grind up food in their gizzards.

Naturally, the particular plant and animal species emus and ostriches consume differ significantly – remember, ostriches are from Africa, and emus from Australia.

However, the most significant diet disparity is related to food ratios.

Unlike ostriches that generally don’t suffer from food shortages, the emus’ environment is not so forgiving. Flocks sometimes travel hundreds of miles to find a new food source. They compensate for the occasional lack of food by accumulating large amounts of fat they use during fasting. During the treacherous journeys on the lookout for sustenance, they can lose up to 50 percent of that body fat.

Emus never eat grass or grown leaves – only shoots. On the contrary, ostriches seem to regularly consume grass and various foliage, usually growing on shrubby plants.

Another stark difference is that ostriches don’t require a constant source of water because they primarily get rehydrated through their diet. Still, they will drink if they come across a water hole.

Emus need a daily supply of fresh water; their movements and migrations often track recent rainfalls.

Natural Habitat

Ostriches live in Africa – their natural range consists of the savannahs of the African Sahel, as well as deserts and semi-deserts of southwest Africa.

The emu is endemic to Australia and found in most of its regions, from coasts to Snowy Mountains. Interestingly, their range spread along with modern agriculture – the water reserves enabled them to inhabit drier areas of the continent’s interior.

The emu subspecies from Tasmania, Kangaroo Island, and King Island became extinct after the arrival of the Europeans.

Still, both emus and ostriches are fairly popular in farms, so they can be found outside their natural habitats.

Breeding and Nesting

Both ostriches and emus nest on the ground. Like with other ratites, males also incubate the eggs and protect the young. Also, both birds engage in at least partially communal nesting.

However, the nests and eggs of the two species are distinct.

Emu nests and nesting behavior

Emu nests are made in a shallow depression in the ground with the addition of grass, leaves, and bark. Since emus live in a harem, several females lay eggs in a single nest, and it can hold 15-25 of them.

Emu eggs are dark in color. Photograph © gomagoti

However, only the males incubate the eggs, not eating, drinking, or pooping for around 56 days.

“Dad emu” is a fierce defender of both eggs and the chicks, driving away even the momma-hens. Once he starts sitting, most hens will leave his territory and likely look for other males to lay more clutches.

The speckled emu eggs have a fascinating, deep dark green coloration and are reminiscent of an avocado or a starry sky (depending on how romantic you are).

- Although it can vary, the average emu egg size is 5.1 in x 3.5 in (13 x 9 cm).

- The average weight of an emu egg is 0.88 to 1.5 pounds (400 to 700 pounds).

- The blue or green coloration is caused by the pigment oocyanin, which deposits onto the eggshells in the hen’s oviduct; the hues can vary.

Ostrich nests and nesting behavior

Nesting is initiated by the dominant male and hen. The male scratches out a nest in the form of a wide and shallow depression in the dirt; the pair mates, and the hen lays the eggs in the middle of the nest.

Ostrich eggs are white or yellowish-white and even bigger in size. Photograph © Tracy

Both share the duty of egg incubation. Soon, other females that mate with the dominant or wandering males join in and lay their eggs in the same nest; the communal nest can number as many as 20 eggs.

The dominant hen’s eggs retain the middle position – the best one for incubation.

Fun fact: due to the ostrich nesting style, the ostrich nest is commonly referred to as a “scrape” or a “dump.”

Ostrich eggs are the largest eggs of any living animal. When you look at the measures, they are imposing.

- The average size of an ostrich egg is 6×5 inches (15×13 centimeters).

- The average ostrich egg weight is 3 pounds (1500 grams).

- Unlike the dark emu egg, the ostrich egg color is yellowish-white.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between an emu and an ostrich?

Emu and ostrich are similar birds, but they differ in terms of size, color, eggs, and nests, as well as the continents they inhabit.

Which is stronger, emu or ostrich?

Although emus and ostriches never have a chance at proving who’s stronger since the natural populations live across the world, the ostrich is physically superior to emu – it is taller, heavier, and faster. Thus, it can probably be declared “stronger” of the two.

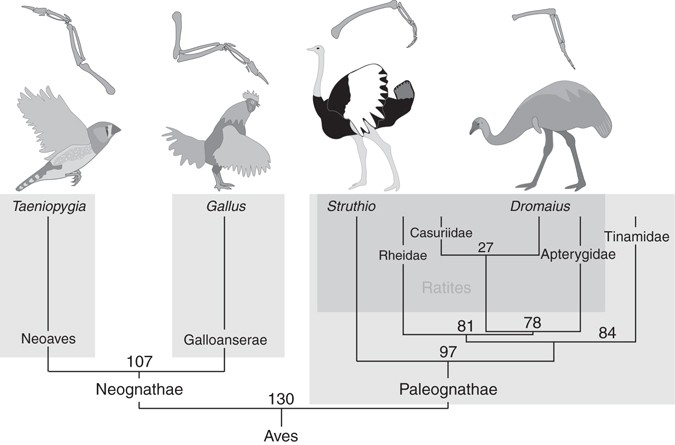

Are ostriches and emus related?

Ostriches and emus are indeed related – according to the official taxonomy, they both belong to an infraclass of birds called paleognaths (Palaeognathae) and share the same defining feature – an almost-reptilian palate (mouth roof), more primitive than in other birds.

Still, the emu has closer living relatives – cassowary, for example, is a more immediate evolutionary kin to the emu than any of the two ostrich species.

In Conclusion

Emus and ostriches are so similar, yet so distinct. The two birds share many traits, such as bipedal, super-fast running, the lack of flying abilities, similar diets, and interesting nesting behaviors.

On the other hand, what sets them apart may be even more interesting to analyze – the differences in sizes, looks, and lifestyles tell a story about their adaptations to the specifics and threats of their respective environments.

But the most important shared feature of emus and ostriches is that they’re such incredible birds – unique avian evolutionary offspring of the dinosaurs!