Gadwalls (Mareca strepera) are a type of dabbling duck common in North America.

Both sexes are known for their modest plumage and the fact that they may be easily confused for other duck species when observed in the wild. If you want to learn more about them, their habits, and how to tell them apart from others, you’re in the right place!

On this page

Identification

Gadwalls are medium-sized dabbling ducks that can be rather difficult to identify in the wild and are often mistaken for other ducks. They’re about the same size as Mallards, measuring 18-23 inches long with a wingspan of 31-33 inches. Their square heads are large and have steep foreheads.

Male Gadwalls in their breeding plumage have an overall grayish-brownish appearance. Their plumage is patterned with dark gray and white on the underside, and brownish, white, and black on the upperside.

Their rear, eyes, and bills are black. In their non-breeding plumage, the male looks almost identical to the female but retains the wing pattern, has less orange on the bill, and is usually grayer above.

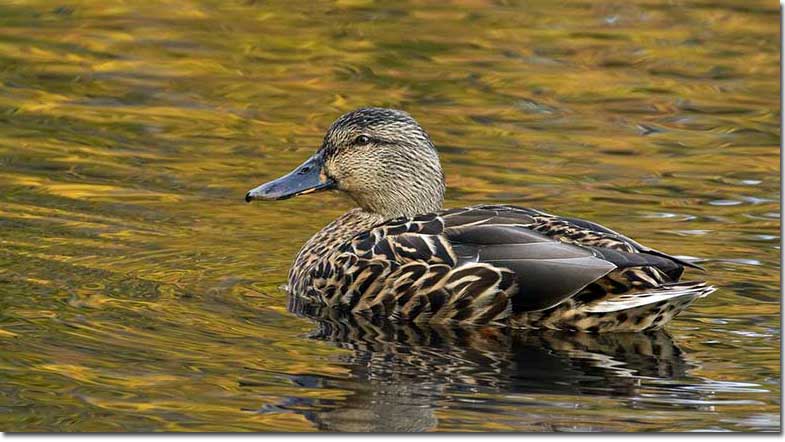

Female gadwall

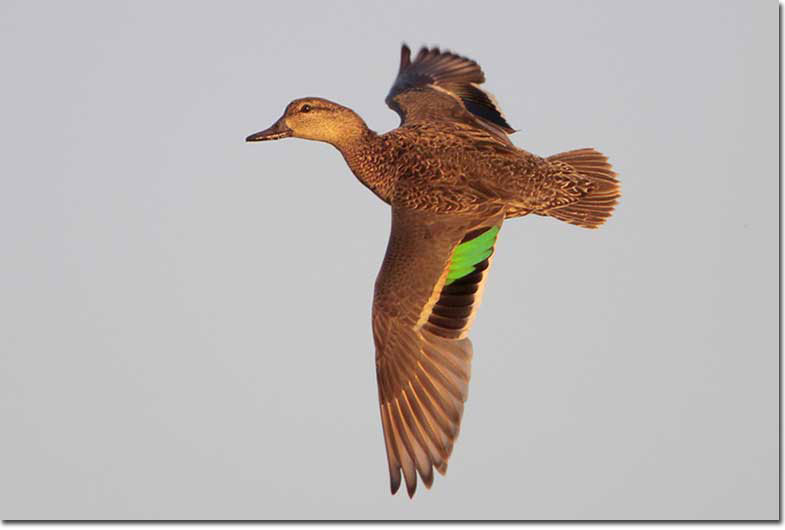

Female Gadwalls look rather similar to female Mallards. They have scaly mottled brown plumage and a uniformly colored pale grayish-brown head. Their bills are dark but have an orange edge to them. Both sexes have white speculum and black greater secondary coverts, most easily visible in flight. Juvenile Gadwalls look very similar to the females of almost every dabbling duck species.

Gadwalls call mostly during their courtship displays and are otherwise quiet. Females quack similarly to female Mallards, but theirs is a higher-pitched and more nasal gag-ag-ag-ag sound. Males whistle and produce grunts that sound like burps.

Food

Gadwalls are omnivores, but they mostly feed on plant material. Their diet includes aquatic vegetation such as pondweed, smartweed, algae, bulrush, grasses, sedges, water milfoil, and their seeds and roots.

In the summer, up to 50% of their diet may consist of animal matter, such as snails, water beetles, mollusks, insects, crustaceans, and rarely small fish. However, during the winter, they feed almost exclusively on plant matter.

Gadwalls often forage with other dabbling ducks, mostly swimming and taking items from the water’s surface. They occasionally dabble with their heads submerged or up-end, rarely diving. However, they can also be spotted in fields eating grain or in woodlands where they consume acorns.

Nesting and Eggs

Gadwalls are monogamous and renew their pair bonds each year. Their courtship displays are rather elaborate and interesting to watch. The male may throw his head back and erect his tail feathers or raise out of the water and let out a loud whistle while descending. When the female accepts the male, she will respond to the display.

Gadwalls typically nest near the water, choosing a place on dry land that has dense vegetation for cover and plenty of material for nest construction.

The pair scouts potential sites by flying low over suitable areas, with the female usually choosing a place near her natal nesting grounds. The male stands guard while the female builds the nest.

She will scrape a depression into the soil, creating the bowl, and lining it with leaves, twigs, grasses, and finally with down feathers plucked from her own body.

These dabbling ducks have one brood a year with 5-13, on average 8-11 eggs in a clutch. Gadwall eggs are white, 1.9-2.4 inches long, and 1.3-1.7 inches wide. The male will usually abandon the female after the eggs are laid to go molt in a safe area, whereas the mother bird is left alone to incubate the eggs for 24-27 days.

As with most other duck species, the ducklings leave the nest shortly after hatching. The mother bird leads them to the water, where they will search for their own food. They can fly at about 48-59 days after hatching and will stay with their mother for up to 10 weeks.

Current Situation

Gadwalls range throughout North and Central America. They’re migratory birds, breeding in the central plains of Canada and the United States and wintering in Mexico and the central and southern United States.

Gadwalls generally inhabit marshes, ponds with nearby grasslands, and sloughs but avoid wetlands bordered by woodlands or other thick vegetation. In the summer, aka during the breeding season, they’re mainly found throughout the ponds scattered throughout the Canadian prairies and the Great Plains.

During migration and in the winter, they’re generally not found near saltwater habitats, but rather near brackish water marshes with abundant vegetation.

Gadwalls are listed as of least concern on the IUCN Red List since their populations have been steady and even in an increase.

Facts

- Gadwalls have an increasing population despite being the third most hunted duck species in North America.

- Gadwall’s migration is triggered by some weather event. Although they’re usually active during the daytime, they migrate at night, presumably to avoid predators and to conserve energy.

- The oldest known Gadwall was at least 19 years and 6 months old.

Similar Species

Gadwalls can be mistaken for various other dabbling ducks across North America. We have brought out four of them and described how to tell the difference.

Female Mallard

Female Gadwalls and Mallards look quite similar. However, Gadwalls lack the blue speculum Mallards have.

American Wigeon

Male American Wigeons, both breeding and nonbreeding, are darker and have more warm brown color in their plumage.

Breeding males also have a white or buffy crown and a green stripe behind their eyes. Nonbreeding males have a white patch on their wings that the Gadwalls don’t have.

Female American Wigeons have a rounder head and dark rings around their eyes.

Their bills are light bluish-gray with a black tip instead of dark gray or dark with orange accents.

Blue-winged Teal

Breeding males have a dark bluish head with a white crescent on their faces and a spotted body.

Female Blue-winged Teals and nonbreeding males have rounder heads and don’t have a white patch on their inner primaries.

Female Green-winged Teal

Breeding males can be easily separated since male Green-winged Teals have a chestnut-colored head and a green stripe behind their eye in their breeding plumage.

Females are harder to distinguish, but female Green-winged Teals are smaller and have a pale, almost white streak at their rear.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Gadwall a rare duck?

Gadwalls are fairly common throughout North America, even across Eurasia and parts of Africa (during migration). Gadwalls are one of the most hunted duck species, but thankfully, their numbers remain stable.

Is a Gadwall a Mallard?

Gadwalls and Mallards are not the same species, even though they share some similarities both in behavior and appearance.

What type of duck is a Gadwall?

Gadwalls are dabbling ducks.

Do Gadwalls quack?

Female Gadwalls quack, males produce other sounds, such as whistles and grunts.