The Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is a medium-sized dabbling duck widespread throughout the wetlands of the world.

Males are recognized for their iridescent green heads and gray plumage, whereas females are known for their iconic quacks. Let’s learn more about one of the most numerous waterfowl species, shall we?

On this page

Identification

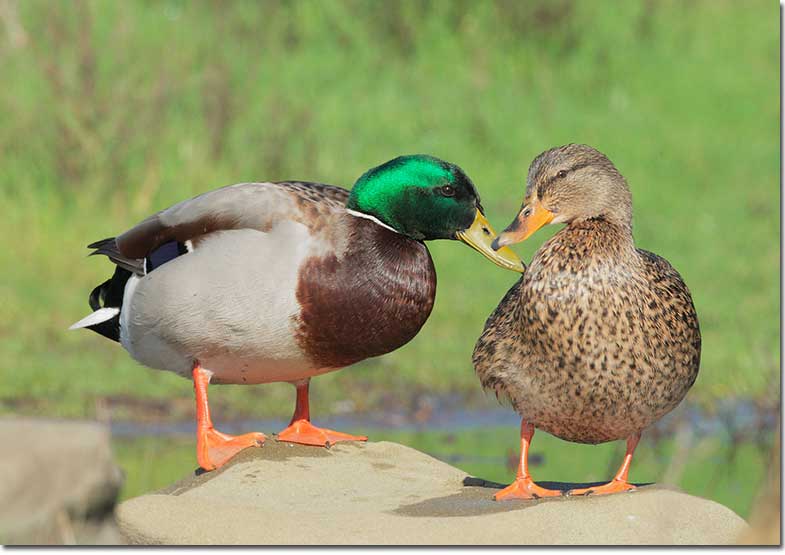

Male

Male Mallards are probably one of the easiest ducks to identify. They have a grayish body, a white neck ring, deep iridescent green heads, a yellow bill, and orange legs. Their breast is chestnut brown, and their black tail feathers are curled. They also have a beautiful blue speculum bordered by white, which is best seen when they are flying.

Identifying them becomes a bit more difficult when they’re in their non-breeding plumage, also known as eclipse plumage. Their plumage is mottled brown, but they generally still have some green patches on their head, a yellow bill, and curled tail feathers.

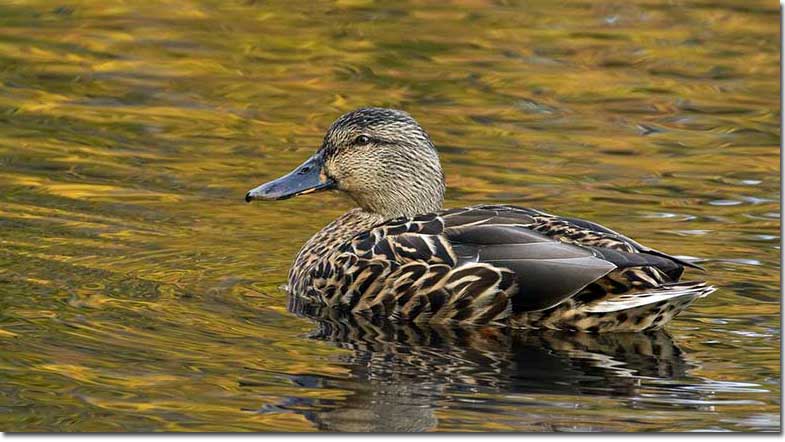

Female

Female Mallards can be quite difficult to distinguish from others, as they look similar to many other species and females of other species. They are mottled in various shades of brown, from cinnamon to dark brown, which makes their plumage look like they have scales.

Their heads are lighter and a bit grayish compared to the rest of their bodies. However, they have a darker brown cap and a line running across their eyes.

Unlike males, their bills are brown and orange, and their tail feathers are straight. Females are also a bit smaller than males. What they have in common is the blue-white-bordered speculum.

Vocalizations

Mallards’ calls sound like what you imagine when you think of a duck quacking. You can also tell whether it’s a female or a male based on the sounds they make.

Female Mallards are louder and make a wider range of sounds. They give a rapid series of quacks that get softer. There may be as many as 10 quacks in a row.

Male Mallards are quieter and give only one to two subsequent quacks. Their quacks are also raspier and softer and can be described as rhaeb. This quacking is most frequently heard during the breeding seasons.

Food

Mallards are opportunistic omnivores with their specific diet depending on the seasonal availability, the stage of the breeding cycle, and competition with other creatures.

Generally speaking, their diet primarily consists of plant matter but also includes insects and small aquatic organisms. However, during the egg-laying period, about two-thirds of the female’s diet consists of animal matter, and ducklings eat insects for the most part.

The plant side of their diet includes a variety of different things, such as seeds, roots, and stems of aquatic plants such as sedges, pondweeds, smartweeds, and grasses. They also eat acorns and waste grain. The animal part of their diet includes snails, slugs, and various insects such as beetles, dragonflies, flies, crustaceans, worms, frogs, mollusks, and small fish.

They often forage in shallow waters, marshes, ponds, lakes, and rivers, where they can easily access their preferred food sources. Their foraging method involves tipping forward, upending, or dabbling on the water’s surface to reach submerged vegetation or small organisms.

Related: Why is bread bad for ducks?

In urban and suburban environments, they may also feed on handouts from humans.

Nesting and Eggs

Mallards generally choose a mate for the breeding season in late fall and winter, but finding a mate might take some up until the beginning of the breeding season. After that, the female, with the male in tow, looks for a suitable nest site.

Females usually build the nest somewhere on the ground near water among concealing vegetation.

Mallard’s nests are shallow depressions in the ground lined with twigs, grasses, and leaves she finds nearby. After incubation, she also adds her down feathers.

The female lays a clutch of 1-15, usually around 7-10 whitish eggs. Mallard eggs measure 2.1-2.5 inches long and 1.5-1.8 inches wide. The mother duck incubates the eggs for about 28 days. After hatching, mother bird leads the fluffy yellow-brown ducklings to water within a day. She then teaches them what and how to forage and provides protection.

The mother continues to care for and protect her brood until they become independent, which typically takes around two months. At that point, they will have gone through their first molt and look a lot like females. Adults grow up to 20-26 inches long, have a wingspan of 32-39 inches, and weigh 1.5-3.5 lb.

Current Situation

Mallards are widespread across the Northern Hemisphere. In North America, they can be found year-round throughout most of the United States. Their wintering range covers the southeastern United States and slightly extends into Mexico, whereas their breeding range covers the majority of Canada, Alaska, and the southern shores of Greenland.

Mallard habitats include a wide variety of wetlands, including marshes, ponds, rivers, lakes, bays, and shallow inlets. They’re also common in city parks. They prefer bodies of water that are less than 3 feet deep and have aquatic vegetation for foraging.

Mallards are listed as of least concern on the IUCN Red List and are one of the most adaptable species out there. They’re one of the most widespread and abundant waterfowl species in the world despite various threats, such as habitat degradation, pollution, poisoning, and hunting.

Facts

- Currently, male ducks are called drakes. However, originally, any wild male duck was referred to as a ‘mallard.’ It is believed to originate from the Old French word for wild drake – malart or mallart.

- Mallards often breed with ducks from other species. They are known to breed with over 40 wild species and an additional 20 domestic breeds. These hybrids may be perfectly fertile. However, this typically requires the other parent to be from the same genus.

- Mallards can go through sex reversal if their sex organs have been damaged or don’t function. This results in males developing female plumage or females developing male plumage.

- The oldest Mallard on record lived to be at least 27 years and 7 months old.

Similar Species

There are quite a few species that are similar to the female Mallard, but only a couple that resemble the male Mallard. Those include the Northern Shoveler and the Common Merganser. Let’s take a closer look at how to tell who is who.

Northern Shoveler

Northern Shoveler is widespread across North America and loves wetlands, just like the Mallard. Male Northern Shovelers have a dark iridescent green head, yellow eyes, chestnut flanks, white chest, and a black rear.

Their most distinguishing feature is their black spatula-like bill. Female Northern Shovelers have a scaly-looking plumage mottled in shades of brown and white. Their bills are also wide but mottled with orange and brown.

Mottled Duck

Mottled Ducks are restricted to the Gulf Coast region of the United States, with their range extending from eastern Texas across the Gulf Coast states to Florida. They prefer coastal marshes, ponds, and shallow wetlands.

Both male and female Mottled Ducks look almost identical to the female Mallard. However, they are slightly larger, have a lighter face, and lack the white that borders their speculum. Males are easier to distinguish from female Mallards as they have a yellow bill.

Common Merganser

Common Mergansers prefer streams and rivers or lakes in more wooded areas across most of North America. They have thin and pointed wings and thin, narrow, reddish-orange bills, whereas Mallards have broad wings and wide bills.

In this case, you only have to distinguish between the males because females differ drastically. Male Common Mergansers have a slimmer body and head. Both have dark iridescent green heads, but the male Mallard has a yellow and wide bill, whereas the male Common Merganser has a narrow and reddish-orange one.

Both have fairly light-colored bodies, but male Common Mergansers are whitish all over and don’t have the dark breast the Mallard has.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you tell if a duck is a mallard?

Male Mallards can be identified by their dark iridescent green head, yellow bill, gray body, brown chest, and black curled tail feathers. Female Mallards have mottled brown plumage and an orange bill with dark markings. Both genders have a blue wing speculum bordered by white.

Is a mallard a duck or a bird?

Mallard is both a duck and a bird since ducks are birds.

Are mallards the only ducks that quack?

Many female ducks quack, but the iconic quacking sound comes from female Mallards.

Are mallard ducks aggressive?

Mallard ducks are aggressive towards other ducks but generally not towards humans.

What do mallards eat?

Mallards eat various aquatic plants, seeds, grasses, insects, worms, and crustaceans, and in urban environments accept handouts from humans.