The Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata) is a dabbling duck recognized for its distinctive large, shovel-shaped bill. It is lined with comb-like projections that enable them to sift through water for tiny crustaceans in shallow wetlands.

The peculiarities do not stop there! Here is everything you need and might want to know about them.

On this page

Identification

Northern Shovelers are medium-sized ducks, with males being slightly larger than females. Overall, they measure 17-20 inches long with a wingspan of 14-30 inches. Their most striking feature is their distinctive bill. It is long, broad, and flattened at the end, resembling a spatula or a shovel, hence the name.

Male

Male Northern Shovelers are rather striking and distinctive looking during the breeding season, even if we do not take their bills into account. They have a white chest, warm reddish-brown flanks and belly, and a black head and neck with green iridescence. Their eyes are yellow and their bills black. In flight, they have pale blue shoulder patches and green secondaries separated by a white band.

Nonbreeding males resemble females. They are mottled brown overall. Their heads and backs are darker brown, whereas their chest and rear are paler, and their flanks have a reddish-brown tinge to them. They still have yellow eyes and black bills.

Female

Female Northern Shovelers have a more subdued appearance compared to their male counterparts, but they still have some distinctive features. They have an overall cryptic and mottled brown appearance that helps them blend into their surroundings. Their eyes are brown and their bills orange. They also have grayish-blue shoulder patches and green secondaries.

Juvenile Northern Shovelers look more similar to females. They have mottled brownish and grayish plumage.

Vocalizations

The calls Northern Shovelers give are variations of low clucks, croaks, and quacks. Overall, they are a quiet species.

During courtship, when alarmed or in flight, males give a clucking and wheezy took-took, which sounds like someone is clicking their tongue. Females give nasal quacks that sound like chuck-ka throughout courtship and the breeding season.

Food

Northern Shoveler’s diet varies depending on the season and habitat. Overall, they are omnivorous, but in the winter, they mostly feed on plant material, whereas during the summer and breeding season, they focus on animal matter.

The plant part of their diet includes seeds and parts of leaves and stems of various aquatic plants. This includes various grasses, pondweeds, and sedges.

The animal part of their diet mostly focuses on tiny crustaceans, but they also eat other aquatic invertebrates such as insects, mollusks, and sometimes even small fish like minnows.

Northern Shovelers are quite versatile when it comes to their foraging methods. Their preferred method of foraging involves them slowly swimming forward, their bill skimming the surface of the water or being partially submerged. They move it side-to-side, drawing water into their bill and then pushing it out from the sides through the comb-like lamellae structures that catch food particles.

They are social foragers and are often drawn to feeding areas with other birds, where they take advantage of food churned to the surface from the activities of other foragers.

Northern Shovelers may also swim in circles to create a whirlpool to bring up food. While they typically forage in shallow water and by dabbling, they are also known to upend and even dive on occasion.

Nesting and Eggs

Northern Shovelers are generally seasonally monogamous, meaning that they pair up for a breeding season but that is as far as it goes. Sometimes males may take a second female as well.

Pairs form on the wintering grounds and the migration preceding the breeding season. Courtship includes several males surrounding a female and then flapping their wings, turning, and bobbing their heads. The male will try to lead the female away from others and if the female accepts his advances, she follows.

Northern Shovelers nest on the ground in dry, grassy areas within 150 feet of water. The female creates a small depression using their bills, feet, and bodies.

It measures about 8 inches wide. She then lines it with dried weeds, grasses, and her down feathers.

One female has only one brood per year with 6-14, usually 8-12 eggs in a clutch. However, when the first clutch is lost, then the female may lay a second one to replace it, albeit with fewer eggs. Northern Shoveler eggs are pale olive, measuring 1.8-2.2 inches long and 1.3-1.5 inches wide. Incubation takes 21-27 days. The female incubates alone and the male leaves soon after she begins the process.

As with most ducks, the young leave the nest with their mother within hours after hatching. They have to feed themselves while the female keeps an eye on them. The young fledge 52-60 days after hatching.

Current Situation

Northern Shovelers range throughout North and Central America, parts of South America, and Eurasia. In the Americas, they mainly breed in northwestern North America, including Alaska, western Canada, the northwestern United States, and the Great Lakes region. They migrate to southern North America and Central and northernmost South America for the winter.

Northern Shovelers are birds of open shallow wetlands, such as flooded fields, wet grasslands, shallow pools, or marshes with some emergent vegetation. They prefer feeding areas with mud bottoms rich in invertebrate life, such as lakes, estuaries, coastal shorelines, marshes, and flooded fields.

Northern Shovelers are listed as of least concern on the IUCN Red List. In North America, their population seems to be increasing.

Facts

- Over 400,000 Northern Shovelers are hunted in North America every year, with the number allowed based on the size of their population. However, they are not the preferred bird the hunters go for and are called the “neighbor’s mallard.” This is because hunters sometimes mistake them for Mallards, shoot them down, and then give them away because their meat is not as tasty.

- The lifespan of Northern Shovelers varies but is around 8-10 years on average. The oldest wild individual on record lived to be at least 16 years and 7 months old.

- If a female Northern Shoveler is scared off her nest, she will often defecate on her eggs. There are many theories as to why. The two most common ones are that it is done in an attempt to deter predators and to make fleeing easier.

Similar Species

Northern Shovelers have quite a few similar species. Males have fairly unique plumage, but females can be quite hard to distinguish. Here are the three most similar species and how to tell them apart.

Cinnamon Teal

Female Cinnamon Teal

Cinnamon Teals breed throughout the western United States and some parts of southernmost western Canada. Males are overall rich rust-colored, have a brownish back, a black bill, and red eyes. Females are mottled brown overall with dark eyes and a black bill.

Breeding males are rather different, with Cinnamon Teal males being deep reddish brown overall with red eyes and black bills, whereas male Northern Shovelers also have white and dark green in their plumage, have yellow eyes, and larger bills. However, non-breeding males look very similar, so look at the size of their bills and the color of their eyes.

Females have a similar plumage but Cinnamon Teals have a dark bill whereas Northern Shovelers have a larger orange bill. Both sexes of both species have a similar wing pattern of pale blue shoulder and green secondaries with a white band in the middle.

Blue-winged Teal

Pair of Blue-winged Teals

Blue-winged Teals breed across most of North America. Males of the two species both have a dark face although with different undertones and male Northern Shovelers lack the white crescent and have bigger bills. Non-breeding males are more similar, but male Blue-winged Teals have dark eyes instead of yellow ones and smaller bills.

Females have similar plumage, but female Blue-winged teals have a darker cap and stripe through their eyes. Female Northern Shovelers have a larger bill that is orange instead of dark. Both sexes of both species have a similar wing coloring.

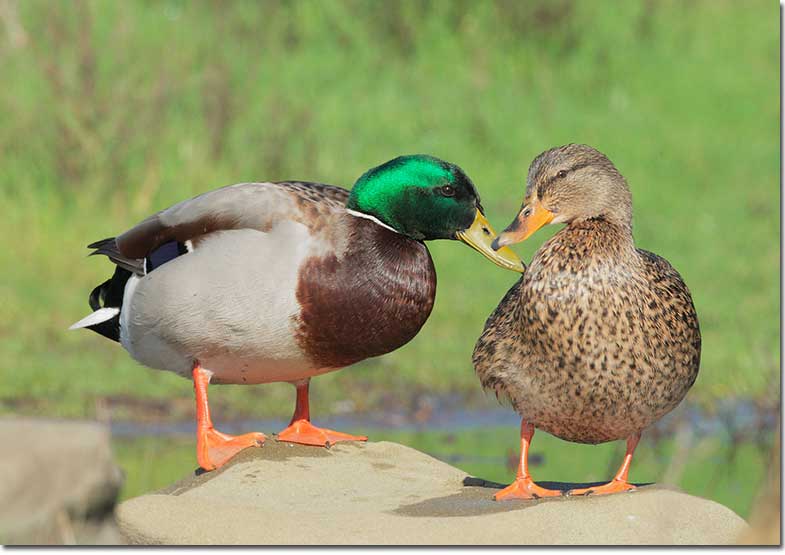

Mallard

Mallard pair

Mallards breed in Alaska and Canada and are resident throughout most of the United States. Males have gray bodies, brown breasts, a white collar around their necks, and dark iridescent green heads and yellow bills. Females are mottled brown with mottled orange-and-black bills.

You can easily tell it is a male Mallard by the fact that it has a uniformly gray body, a brown not white breast, and a smaller yellow instead of a large black bill. Female Mallards have a dark stripe through their eyes, a dark cap, and a smaller bill. Both male and female Mallards have a blue speculum instead of green secondaries.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Northern Shovelers get their names?

Northern Shovelers are named for their distinctive bill shape, resembling a shovel, which they use to filter food from the water.

Do male and female Northern Shovelers look different?

Male and female Northern Shovelers look different with males boasting more vibrant colors. However, during the non-breeding season, males look more similar to females.

What color are Northern Shovelers wings?

Northern Shovelers have pale blue shoulders and a green speculum separated by a white band.

jack foster

Saturday 13th of January 2024

I once was told it takes 7_years for a male shoveler to reach 100% full plumage??

Patrick O'Donnell

Wednesday 17th of January 2024

@Jack- It doesn't take that long for male Northern Shovelers to show their full adult breeding colors but they do change their plumage a couple of times each year. In their first year, these ducks have a "basic" flightless plumage that makes them look more like their female counterparts. They then molt into their first adult breeding or "alternate" plumage by January. This plumage differs in a few small ways from their second alternate plumage acquired the following January.

With that in mind, we can say that male Northern Shovelers attain their full adult breeding plumage when they are about one and a half years old.