The American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) is among North America’s largest birds.

These striking white birds adorn inland wetlands during the breeding season and coastal habitats during winter. They breed in colonies and may often forage together as well, herding fish to the shallow waters. Let’s explore this species further!

On this page

Identification

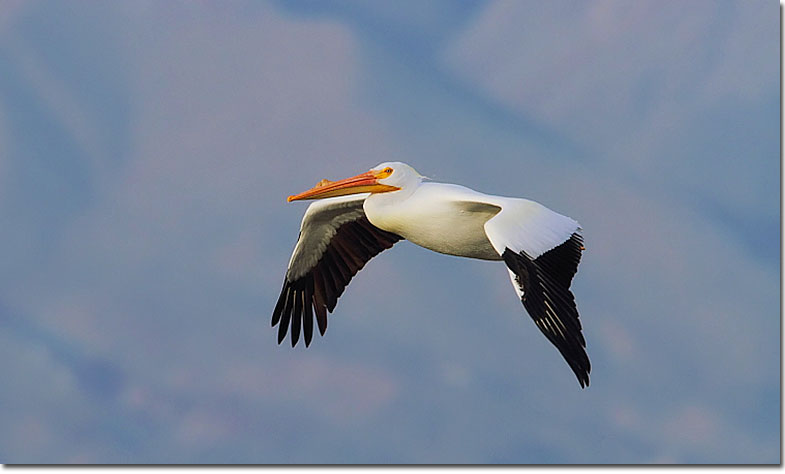

American White Pelicans measure 4-6 feet long with a wingspan of 8-10 feet. In flight, their long necks are curved into an S-shape, they have short and squared tails, and their wings are very broad. They have primarily white feathers overall, hence the name. The white plumage is accentuated by contrasting black flight feathers on their wings.

The head of the American White Pelican is distinctive with its long pale pink to yellow bill and fleshy throat pouch.

During the breeding season, the adults develop a noticeable knob on the upper mandible and have a crest of white airy feathers that slightly continue down the back of their neck.

This knob is shed after the breeding season and their upper head obtains a grayish hue, especially noticeable around the crest area.

Juvenile American White Pelicans are white overall as well. However, they have variable amounts of gray on their wings, head, neck, and back.

Vocalizations

American White Pelicans are not known for being particularly vocal. The sounds they produce are mostly done during the breeding season.

They produce low, hoarse grunts on the nesting grounds either when in an altercation or during courtship. Chicks squawk to beg for food.

Food

American White Pelicans are carnivores, specifically piscivores. Their preferred prey consists of schooling fish, typically measuring less than half the length of their impressive bills.

Among the common prey species are minnows, carp, shiners, perch, and various other shallow wetland species. Additionally, they may target tui chub, salmon, crayfish, salamanders, trout, tadpoles, and jackfish.

In shallower waters, they often forage cooperatively by lining up and skillfully herding fish toward the shallows. On the other hand, when venturing into deeper waters, they often opt for solitary hunting, although their success rate tends to increase when they work together in groups.

They catch their prey by dipping their bill into the water and capturing the fish into their throat pouch. During the day, American White Pelicans primarily rely on their keen eyesight to locate prey.

However, they are versatile hunters, and especially during the breeding season, they may hunt at night. During these nighttime forays, they rely more on their sense of touch to locate prey.

While they do not engage in plunge-diving, American White Pelicans are opportunistic feeders and have been observed stealing food from other waterbirds, including cormorants, fellow pelicans, and gulls.

Nesting and Eggs

American White Pelicans are social creatures when it comes to breeding, forming colonies of up to 5,000 breeding pairs. Pairs start forming once most of the birds have arrived on the breeding grounds.

Courtship rituals include circular flights, strutting walks, head swaying, and gracious bowing. They are monogamous with the bonds persisting throughout the breeding season, although the mystery remains as to whether the pair comes together in the subsequent years or not.

Finding and establishing a nesting site is done more or less at the same time across the colony. Choosing a suitable spot is crucial, and the pairs opt for relatively flat areas on gravel, sand, or soil, often in proximity to other pelican families at a similar stage of the breeding cycle.

Both partners use their bills to fashion a shallow depression roughly 2 feet across with a rim no higher than 8 inches. Occasionally, they may incorporate nearby vegetation.

They have only one brood in a year with one to two eggs in a clutch. American White Pelican eggs are chalky-white and measure 3.3-3.7 inches long and 2-2.2 inches wide. If an egg is lost, there’s no replacement, and if both are lost, the nest is deserted.

Incubation lasts for 63-70 days. The first part of the incubation is done by one of the parents warming the eggs under their webbed feet and the second part by regular brooding. The parents dutifully feed their offspring through regurgitation until the fledglings are ready to leave the colony, typically at 10 to 11 weeks after hatching.

Current Situation

During the breeding season, American White Pelicans range across North America. Their presence is prominent in the western and central parts of the continent, extending from the central reaches of Canada down to Mexico.

These pelicans are frequently observed in the interior portions of the United States, particularly around the prairie regions. They migrate to the southern parts of the US and Mexico for the winter. There are also some resident populations along the Gulf of Mexico.

American White Pelicans inhabit a variety of wetland environments. Their choice of habitat depends on the season and activity. They often choose to breed inland on islands in shallow water. In winter, they are primarily found along the coast in protected bays and estuaries. During migration and foraging, they can be seen on lakes and rivers, preferably shallow ones.

The American White Pelican is listed as of least concern on the IUCN Red List. Their population has been increasing in recent years thanks to conservation efforts. However, it is important to keep in mind that they are highly sensitive to human disturbance and habitat degradation and destruction.

Facts

- American White Pelicans use their bill and bill pouch to scoop up prey from the water. However, they do not use the pouch to carry their prey but rather drain the water and then swallow their catch before taking off.

- American White Pelican chick embryos emit squawks to let their parents know if they get too cold or hot.

- Although American White Pelicans lay two eggs, often only one of the chicks survives because the first (and generally strongest) chick tends to end up killing the other. Only 9.7% of clutches within a colony managed to raise two.

- American White Pelicans live for around 15 years on average in the wild. The oldest individual on record lived to be at least 23 years and 6 months old.

Similar Species

While the American White Pelican is distinctive in many aspects, there are several other bird species with similarities in certain features. Here are three of the most similar species, how they look like, and how to tell them apart.

Wood Stork

Wood Storks are primarily found in the southeastern United States, extending from the Carolinas to Florida and throughout the Gulf Coast, as well as parts of Central and South America. These large wading birds have distinctively dark bald heads and long, down-curved bills. They have white plumage, black flight feathers, and a wingspan of about 5 to 6 feet.

If you see them up close, look at their faces. Wood Storks are bald and dark with a dark downcurved bill, whereas American White Pelicans have a white feathered head with a yellowish bill. In flight, look at how they keep their legs and neck.

Wood Storks fly with necks outstretched and legs trailing far behind them, whereas American White Pelicans keep their necks tucked in an S-shape and legs tucked in.

Whooping Crane

Whooping Cranes are a very rare sight and have a very limited range. They are tall, elegant birds with white plumage, black wingtips, a red crown, and a black mustache stripe.

Up close on the ground, you can tell that they have longer legs, shorter bills, and a more elongated body. In flight, they keep their necks outstretched with their legs trailing far behind whereas American White Pelicans tuck their necks in and have short legs.

Whooping Cranes also have black only on their wingtips, whereas all of the American White Pelican’s flight feathers are black.

Brown Pelican

Brown Pelicans are found along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North and South America, ranging from the southern United States through Central America and down to the northern regions of South America. It is a distinctive species with dark brown plumage, a contrasting white head and neck, and a long bill.

Brown Pelicans are darker and smaller than American White Pelicans. They are very similar in shape, but Brown Pelicans are mostly brown and lack the white-and-black contrast on their wings the American White Pelicans have.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the bump on the American White Pelican?

The bump on the American White Pelican’s bill is a flattened bony horn that they grow for the breeding season and shed when the eggs are laid. It is believed to be used to find a partner.

How big is the American White Pelican?

American White Pelicans are among the largest birds in North America, measuring 4-6 feet long.

Do American White Pelicans migrate?

Most of American White Pelicans migrate but there are small resident populations.