Species extinction is the most unfortunate event in biology. Although extinctions occur naturally, the disappearance of many species over the last 500 years has been caused or greatly boosted by human activity.

Today, more than 1,480 bird species are threatened, and 223 are considered Critically Endangered – facing a high extinction risk.

Recently, another ten bird species have been declared extinct as of 2023, evoking a reasonable feeling of loss and grief in the bird-loving community.

On this page

Birds That Went Extinct in 2023

Toward the end of 2023, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delisted 21 animal species from the Endangered Species Act due to extinction.

The Service ultimately declared these species extinct after there was no trace of them for decades.

Here is the list of birds considered officially gone since 2023.

- Bachman’s Warbler

- Bridled White-eye

- Kauaʻi ʻōʻō

- Kauaʻi ʻakialoa

- Large Kauaʻi Thrush

- Kauaʻi Nukupuʻu

- Maui ʻakepa

- Molokaʻi Creeper

- Maui Nukupuʻu

- Poʻouli

Most of the listed birds – 8 out of 10 – were forest birds of Hawaii.

Why? The introduction of mosquitoes carrying avian pox and avian malaria to the Hawaiian Islands (via European and American ships) has gravely impacted the geographical distribution and population of highly susceptible Hawaiian honeyeaters (ʻōʻō). Habitat destruction, overgrazing, introduced predators, and hunting also played a role.

Related: Bird facts & statistics everyone should know

The extinction of Kauaʻi ʻōʻō means that the ʻōʻō family has now been wiped out entirely – the first such case in modern times.

Why Do Birds Go Extinct?

Although extinctions do occur naturally, current extinction rates are much higher than normally expected, prompting worries about a new mass extinction event.

Unfortunately, birds are at the forefront of the current extinction crisis as they face substantial population declines. Scientists estimate that 3 billion birds have been lost in the last 50 years in North America alone.

Understanding Extinction

Extinctions are a part of the planet’s evolutionary history. As the environment constantly changes, some species go extinct while new ones evolve and take over. Estimates are that 4 billion species came into existence throughout Earth’s history; today, 99% of them are extinct.

Scientists have calculated the “natural” rate of extinction frequency:

- Every million years, 10% of species go extinct

- Every 10 million years, 30% of species go extinct

- Every 100 million years, 65% of species go extinct

However, there are times when the extinction rate is abnormal, unfolding at a much faster pace and throwing the biosphere off balance for a while. And in geologic terms, “a while” may be a few million years. We call these situations mass extinction events.

Mass Extinction Events

There were five mass extinction events up to the Holocene – the epoch we live in.

The best-known one took out the dinosaurs – it was the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event around 66 million years ago. A presumed asteroid impact spelled doom for 75 percent of all plants and animal species that existed at the time.

Interestingly, all modern birds living today are descendants of the asteroid impact’s dinosaur survivors.

Today, species die out much quicker than the natural extinction rate. Scientists have gathered enough evidence to conclude that the Sixth mass extinction might be underway.

This time around, there is no asteroid or prolonged volcanic activity. The proliferation of one species – modern humans – and our transformative activities are changing the environment so rapidly that most plants and animals can’t adapt.

Overall, animal populations have declined an average 68 percent since the 1970s. According to a recent study, species are disappearing at a rate 35% higher than expected. It says, “Increasing human impacts accelerated the rate of extinction in the 20th century over that in the 19th; the predominant cause of species loss is habitat destruction.”

Modern Bird Extinctions

According to researchers, bird species have been going extinct at an alarming rate since 1500, matching the dawn of global European exploration – and colonization.

The current bird extinction rate has been approximately one species yearly – 100 times faster than the natural rate. Human activities have caused some 500 bird species worldwide to go extinct over the past 500 years.

And it might get worse. The 21st-century extinction rates are predicted to accelerate to roughly ten additional extinct species annually.

List of Notable Bird Extinctions

Dodo

Raphus cucullatus

The Dodo is the best-known extinct bird and one of the symbols of human-driven extinction.

This quirky-looking, tall, flightless pigeon relative, endemic to the island of Mauritius, was hunted to extinction quickly after the arrival of the Europeans. Its lack of fear, benevolence, and absence of defense mechanisms was misused by the Dutch explorers, who made this iconic bird an easy meal.

Besides direct hunting, destroying forest habitats and introducing non-native animals (such as pigs feeding on the Dodo eggs) also played a major role in its extinction.

The first mention of Dodo was in the journal of a Dutch naval officer in 1598. The last confirmed Dodo sighting happened in 1662, with the bird presumed to be fully extinct by 1690. After the Dutch colonization of the island, the species couldn’t last an entire century.

Carolina Parakeet

Conuropsis carolinensis

Because we associate parrots with tropical environments, many aren’t aware that there were parrots in the eastern United States just 150-200 years ago.

The Carolina Parakeet was as brightly colored as its southern cousins, with green, orange, and yellow feathering. Once a common species across the eastern U.S., they became rare by the mid-19th century and extinct at the beginning of the 20th century. The last known Carolina Parakeet died in 1918.

The only North American parrot faced various pressures. Persecution by farmers, habitat loss, decorative feather trade, and possibly an introduced poultry disease all ultimately led to its disappearance.

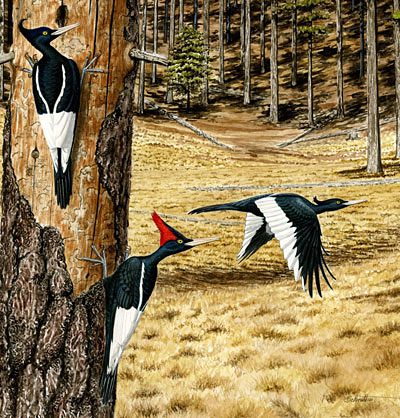

Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Campephilus principalis

The Ivory Billed Woodpecker is a legendary bird of the southeastern U.S. Also locally known as the ‘Lord God bird,’ it has evaded being listed as officially extinct for years despite the lack of clearly reliable sightings.

Sporadic but unproven records continue to instill hope that the species will continue to survive in small numbers somewhere in the depths of Louisiana. Still, most presume it to be extinct.

This showy, large woodpecker lived in bottomland hardwood forests and temperate coniferous forests in the Southeastern U.S. and Cuba. Cuba has (or has had) its distinct subspecies, Campephilus principalis bairdii.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker had an extra-strong bill with unmatched wood carving abilities. The pairs likely mated for life and often reused cavities in large old trees. Due to their size, they needed quite an extensive range to reproduce successfully.

Unfortunately, intensive logging and wetland draining after the Civil War obliterated the forests suitable for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Also, hunting for food, baiting, and collections influenced the species’ demise.

The last reliable sighting of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker happened in 1944 in Louisiana. Eighty years later, we still lack a scientific consensus on whether the bird is truly gone. True, many species whose last sightings happened much more recently were nevertheless declared extinct, so delisting seems to be a bit overdue. On the other hand, there are constant reports of Ivory-billed woodpeckers, but none of them has been unanimously confirmed to this date.

The Cuban Ivory-billed woodpecker was last observed in 1987.

Labrador Duck

Camptorhynchus labradorius

The extinction of the Labrador Duck is still shrouded in mystery. The duck with a strange bill and largely unknown biology was rare even before the arrival of Europeans. They likely bred in remote and inaccessible areas of the Canadian east coast, but no one ever found any nests. The species was last observed in 1875.

Scientists presume the Labrador Duck might have had a highly specialized diet because of the specific bill lined with comb-like lamellae. Species that depend on a limited resource are more sensitive to extinction because if the particular food becomes scarce, the entire population might crash. We might never know if hunting or egg collection contributed to the extinction of this unique waterfowl species.

Great Auk

Pinguinus impennis

© Free Public Domain Illustrations by rawpixel, originally from Birds of America.

The Great Auk was the largest species of the Auk family (Alcidae) to survive into the modern age – but only for a while. Three fishermen killed the last pair in June 1844 on the island of Eldey near Iceland, ending the species and its last known breeding attempt.

This flightless seabird lived and bred in colonies on rocky islands of the North Atlantic coast, including Iceland, Faroe Islands, St. Kilda, and Funk Island. Clumsy on land but agile on water, they were excellent fish hunters.

Fishermen, rather than scientists, mainly observed the Great Auks, so their behavior could have been recorded more objectively. Still, many accounts state they had no innate fear of humans, which likely contributed to their demise – just like in the case of the Dodo. They were easily hunted for food (fat and eggs), feathers, as specimens, and even used as fishing bait.

The gentle giant, standing at 75 to 85 cm (30 to 33 in), was also the original “penguin.” Since it had lived in the North, Europeans knew the species before the ‘true’ Penguins of the Southern Hemisphere and named the entire group after one of the Great Auk’s alternative names. Still, auks and penguins aren’t closely related.

Passenger Pigeon

Ectopistes migratorius

It seems unlikely that European settlers to North America could exterminate the Earth’s most abundant bird in only a couple of centuries. Even John James Audubon didn’t believe it was possible. Yet, that’s exactly what happened to the Passenger Pigeon.

This pigeon species was endemic to North America and its deciduous forests, with main breeding grounds around the Great Lakes. It got its name for its migrating habit. The enormous flocks were regularly on the move in search for food and shelter, creating surreal noise and darkening the skies from their sheer numbers. Scientists estimate their population numbered between three and five billion individuals.

The Passenger Pigeon was hunted relentlessly for food. The protein-hungry settlers, barely surviving harsh winters, killed pigeons in various gruesome ways. The slaughtered birds were later loaded onto trains and sent to booming cities like New York.

The gregarious nature of Passenger Pigeons that protected them against many predators proved to be a weakness in their encounter with humans – so many animals could be killed in one strike.

The last known Passenger Pigeon, a female from the Cincinnati Zoo named Martha, died in 1914, putting a sad end to the existence of one of North America’s keystone animal species.

Eskimo Curlew

Numenius borealis

The Eskimo Curlew used to be among the most numerous shorebirds of the far north – Alaska and western Arctic Canada. It was an elegant bird with a distinct melodic call. However, neither its numbers nor lovely qualities could have saved it from extinction.

All until the 1870s, Eskimo Curlews massively migrated across the Americas – from Canada to New England to South America for overwintering.

In springtime, the returning flocks relied on the insects of the Great Plains – especially the Rocky Mountain locust – for sustenance.

However, this crucial food source and habitat disappeared as settlers occupied the West and converted prairies into agricultural land. To top that, they were mercilessly hunted for feathers and food – especially after the disappearance of the Passenger pigeon.

The famous Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed in 1918 but came in too late for the Eskimo Curlew – they became very rare after 1890. The last reliable sightings were in the 1960s and 1987.

Still, the Eskimo curlew continues to be listed as Critically Endangered – Possibly Extinct for the time being. If any minuscule population still exists, the oil and gas extraction in its northern range and land development in its central range remain grave threats.

Laughing Owl

Ninox albifacies

Laughing Owl was endemic to New Zealand. A sole member of its genus, it was named after its distinct calls – the repetitive shrieking cries that sounded like laughing or barking.

In the 1800s, right upon the arrival of European immigrants, it was a common species, especially abundant on the South Island. Just one century later, the last known individual was discovered dead in Canterbury in 1914.

The Laughing Owl was a ground feeder, hunting any small vertebrate or invertebrate it could catch. Although the settlers had hunted it, the invasive mammals that came along ultimately destroyed the population.

It wasn’t the infamous rats because Laughing Owl was large enough to make them a part of its diet. However, the rats did exterminate most of the owl’s original prey. Experts think the introduction of stoats, known as fierce predators of anything they can subdue, spelled doom for the ground-feeding bird. Changes to habitat also played a role.

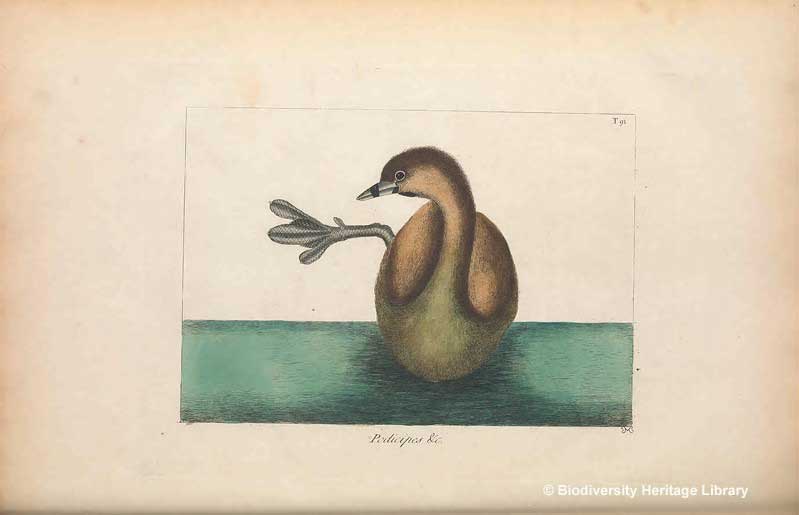

Atitlán Grebe

Podilymbus gigas

The Atitlán Grebe or Poc was a sizeable flightless water bird from the Grebe family, closely related to the surviving Pied-billed Grebe. It was first described in 1929 and declared extinct only about 60 years later, in 1990.

It had dark brown plumage and a pied bill and was endemic to a single lake – Lago de Atitlán in Guatemala. The common and the Latin names speak about the size of this grebe – it was up to 50 cm long.

The decline began in 1958 when non-native fish – the smallmouth and the largemouth bass – were introduced into the lake and depleted it of the Grebes’ natural prey. At the same time, they ate Grebe chicks.

The influence was so significant that in 1965 – less than a decade since the bass introduction – the Atitlán Grebe population was down to only 80 individuals.

Thanks to the efforts of American ecologist Anne LaBastille it seemed like the population could recover. Unfortunately, the 1976 earthquake fractured the lake bed, causing a drop in water level. Anne also documented other pressures – the growing pollution and real estate development at the lake. Finally, the civil war prevented scientists from continuing their conservation actions.

The remaining few Giant Grebes continued diminishing or hybridizing with the Pied-Billed Grebe. The last two birds were observed in 1989.

Dusky Seaside Sparrow

Ammospiza maritima nigrescens

Image credit: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The Dusky Seaside Sparrow was a non-migratory subspecies of the Seaside Sparrow with distinct dark plumage. It lived in the salt marshes of Meritt Island and along the St. John’s River (Florida). Its geographic isolation from other Seaside Sparrows made this subspecies unique regarding its looks and genetics.

The causes of the Dusky Seaside Sparrow’s demise were land conversion and pesticide use. Experts believe that the first wave of the decline occurred with massive DDT use when many North American birds suffered immense population losses.

In 1981, only five individuals remained – and unfortunately, all were males.

Despite the attempts to at least partially save the subspecies by hybridizing the survivors with Scott’s Seaside Sparrow females, all the attempts failed.

The Dusky Seaside Sparrow is likely the first bird that went officially extinct in Disneyland. The last known specimen died on Walt Disney World’s Discovery Island in 1987.

Imperial Woodpecker

Campephilus imperialis

Imperial Woodpecker painting by John Schmitt. Image credit: allaboutbirds.org

If it is still out there, the Imperial Woodpecker is the biggest woodpecker in the world. It depended on large dead pines found in its only habitat – Mexico’s coniferous and mixed montane forests.

The impressive bird is still listed as “Critically Endangered (possibly extinct)” by BirdLife International and IUCN. If the population still exists, it is only tiny and basically unsustainable. However, the more likely scenario is that these birds haven’t survived beyond the 1990s. There would need to be more suitable large old trees pines to keep them going.

Because it requires specific ecological conditions for survival, the Imperial Woodpecker population probably never numbered more than 8000 individuals. Still, in the 1950s, it visibly plummeted. Besides the logging itself, researchers subsequently found that logging companies orchestrated an eradication campaign on the false presumption that these birds damage valuable timber.

The last footage of the Imperial Woodpecker came from 1956. After that, there were sporadic sightings, but none were entirely reliable.

San Clemente Wren

Thryomanes bewickii leucophrys

As its name suggests, San Clemente Wren was a small bird endemic to San Clemente Island, just off the southern coast of California. It was actually a subspecies of the Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), but some ornithologists considered it a separate species.

The last report of the San Clemente Wren comes from 1941. Island ecosystems are isolated and sensitive to disturbance. In the case of this wren and a few other bird species, habitat destruction by goats drove them to an unfortunate end.

Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō

Moho nobilis

Many of the previously listed extinct species were survived by their close relatives, which offers at least some comfort. However, now we’ll get to know the best-known member of the extinct bird genus and family – the Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō.

The name of these endemic Hawaiian honeyeaters is pronounced as “Moho.” They were colorful birds notable for their appearance and melodic vocalizations. Also, they played an important role in native Hawaiian folklore.

Europeans introduced several elements lethal to Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō and its close relatives. Modern weapons made it easier to kill thousands of birds in one hunt. Deforestation increased. The introduction of grazing livestock changed the terrain. Novel non-native predators ate the birds and their eggs. Finally, mosquitoes (that didn’t naturally exist on the Hawaiian islands) brought deadly avian diseases.

Scarce since the end of the 19th century, the Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō was last seen on the slopes of Mauna Loa in 1934.

Kauaʻi ʻōʻō

Moho braccatus

The Kauaʻi ʻōʻō was a relative Hawaiʻi ʻōʻō, native to the island of Kauaʻi. It was the last member of the ʻōʻō family. There are records of the bird after 1987; now, the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō has officially been declared extinct.

The main reasons for Kauaʻi ʻōʻō disappearance were introduced predators, avian diseases, and habitat loss.

Its delisting from the endangered species list marks the first time in modern times that an entire avian family has been extinct. It is a tremendous loss for the avian biodiversity, the natural world, and Hawaiian indigenous human communities.

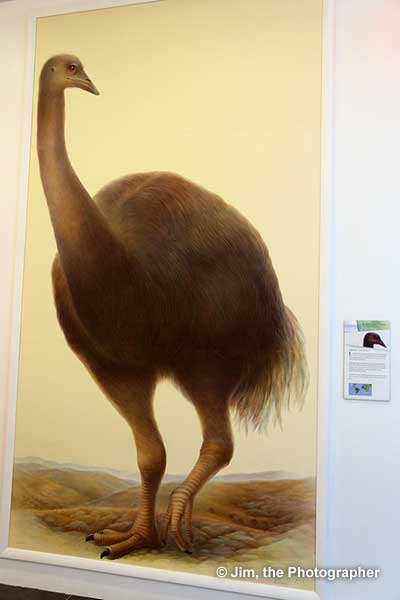

Giant Elephant Bird

Aepyornis maximus

Madagascar’s Giant Elephant Bird is considered the largest modern bird to ever walk the Earth. It was a flightless ratite, like today’s ostriches and emus, or cassowarys, but its closest genetic relative seems to be the Kiwi of New Zealand.

The adults measured up to 3 meters in height and up to an estimated 860 kg in weight. The eggs were the largest of any terrestrial vertebrate.

Despite their terrifying looks, the Elephant Bird was a herbivore. Its role in seed dispersal and vegetation distribution likely made it a keystone species that influenced the dynamic of the entire ecosystem. Also, they seemed to be shy, nocturnal and adapted to the forest lifestyle – like today’s cassowary.

The Giant Elephant Birds have been extinct at least since the 17th century, but it is more likely they died out much earlier – around 1000 years AD.

Scientists are unsure what drove them to extinction, along with other endemic Madagascar vertebrate giants. Also, the role of humans is unclear. Some of the hypotheses include climate aridification, human impact in the form of hunting, habitat change, and introduction of competing cattle or diseases.

New Caledonian Lorikeet

Charmosyna diadema

The New Caledonian lorikeet is a critically endangered and possibly extinct lorikeet parrot endemic to the island of New Caledonia. Known only from a couple of specimens, this small and inconspicuous arboreal parrot is known to live in the island’s thick forests. However, it hasn’t been reported since 1976.

The possible numbers of New Caledonian lorikeet are unknown, and so are the reasons behind its disappearance. All New Caledonian parrots faced a sharp decline and possible extinction, so they probably suffered from the same problems. Forest destruction, rat introduction, and foreign diseases such as avian malaria could all be factors.

The species’ innate elusiveness and the difficult terrain with poor visibility make it hard to prove or disprove its survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many bird species are considered to be extinct?

Newer estimates suggest that 500 bird species have been extinct in the last 500 years, but there were more extinctions in the past.

What is the most famous extinct bird?

The opinions may vary, but the most famous extinct bird was probably the Dodo. The saying “dead as a dodo” unfortunately says it all.

What bird came out of extinction?

Several well-known bird species returned from the brink of extinction through conservation efforts. These include the California Condor, the Bald Eagle, the Whooping Crane, the Bald Ibis, and the Lear’s Macaw. They are just some of the astonishingly beautiful and valuable birds to be saved from being gone forever.

Who was the biggest extinct flying bird?

Pelagornis sandersi was an albatross-like bird that lived 25 to 28 million years ago. It had a toothed bill for catching fish and the largest-known avian wingspan – its astonishing wings measured 20 to 24 feet (6.1-7.4 m).

The fossils of this impressive seabird were discovered during the renovation of the Charleston Airport in South Carolina in the 1980s. However, the species wasn’t identified until a decade ago.

Conclusion

It takes serious amounts of denial to remain unalarmed by bird extinction facts and figures. However, conservation efforts effectively fought extinction before, reversing sharp declines of species such as the Bald Eagle and California Condor. Hopefully, the conservation programs will receive more attention and appropriate funding in the future – both we and the birds need them.

Prominent bird extinctions remain as cautionary tales about human environmental impact and short-sightedness. If we want to save what’s left, we must reflect on these stories – because those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Pauline Hodkiewicz

Saturday 3rd of February 2024

Your blog is a breath of fresh air.