The White-crowned Sparrow is a large sparrow. These birds are mostly winter birds across the United States.

However, they live year-round in the mountains of the west and the West Coast. You can start looking for White-crowned Sparrows in September.

They inhabit low foliage along trails, roadsides, fields, and your yard until early spring. Watch for flocks of these birds scurrying through overgrown fields and brushy borders. Then, as the spring months approach, listen for their sweet, thin whistle.

On this page

Identification

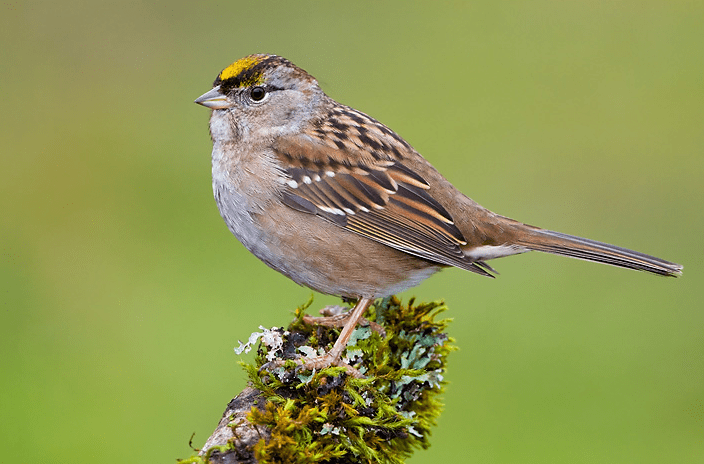

At a glance, White-crowned Sparrows can look like plain, pale-gray birds. However, when you take a closer look, you’ll be able to see their yellow or pale pink bill and very bold black-and-white stripes on the head.

These birds are 5.9 to 6.3 inches long, weigh 0.9 to 1.0 ounces, and have a wingspan of 8.3 to 9.4 inches.

Female White-crowned Sparrows look identical to male White-crowned Sparrows.

White-crowned Sparrows do have some regional differences. Birds that breed in the Rockies and east of Hudson Bay tend to have black lores that merge with black head stripes and pink bills.

Birds that breed from Hudson Bay to Alaska tend to have gray or white lores and orange bills. Lastly, birds that breed along the Pacific Coast are duller white head stripes and tend to have yellow bills.

Food

White-crowned Sparrows mainly consume the seeds of grasses and weeds. However, they also consume a good number of insects like beetles, wasps, and caterpillars, as well as other insects during the summer months.

They also eat grains such as wheat, oats, corn, barley and fruits like blackberries and elderberries.

You’ll be happy to know that White-crowned Sparrows will feed from bird feeders. They’ll eat a variety of seeds, but they prefer sunflower seeds. They will eat from bird feeders but will be most comfortable feeding on the ground.

You can either use a ground feeder or sprinkle the seeds on the ground underneath your feeders. Adding a brush pile to your yard is another way to attract these birds to your yard.

Nesting and Eggs

White-crowned Sparrows usually build their nests fairly low; they’ll place them in shrubs at heights anywhere from 1.5 to 10 feet tall in shrubs.

Copyright Glenn Bartley

Across the subarctic and arctic portions of this bird’s range, they nest in the tundra and have limited options on where to put their nests. As a result, they often put their nests on the ground. The ground nests are hidden among mats of lichens, ground-hugging shrubs, and mosses.

Female White-crowned Sparrows create their nests out of coarse grasses, twigs, dead leaves, pine needles, bark, and moss. They line the cup of the nest with hairs and fine grasses. The finished nest is around 2 inches deep and 5 inches wide. It takes the female 2 to 9 days to finish the nest.

- Clutch size is 3 to 7 eggs.

- White-crowned Sparrows have 1 to 3 broods per breeding season.

- Egg length can be anywhere from 0.8 to 0.9 inches (1.9 to 2.4 centimeters).

- Egg width can be anywhere from 0.6 to 0.7 inches (1.4 to 1.8 centimeters).

- The incubation period is 10 to 14 days.

- The nestling period is 8 to 10 days.’

- Their eggs are greenish, greenish-blue, or bluish and have reddish-brown spots.

Current Situation

White-crowned Sparrows are a common and widespread bird. Their population has continued to hold steady between the late 1960s and 2019. They have an estimated breeding population of 79 million, making them a species of low concern.

Facts

- White-crowned sparrows have an incredible alertness mechanism. This natural mechanism allows these birds to stay awake for a maximum of 2 weeks when migrating.

- White-crowned Sparrows are loyal to their wintering territories. Consequently, they often return to the same areas every year.

- Despite the White-crowned Sparrow’s small size, they’re powerful fliers! When migrating, these birds can travel 300 miles in one night!

- Through banding operations, it was discovered that the average life span of White-crowned Sparrows is around 16 months. However, the oldest White-crowned Sparrow lived to be just over 13 years.

- If a female White-crowned sparrow notices any danger, like a predator, she will use a distraction display. She’ll run away from the nest while wagging her tail feathers.

Similar Species

White-crowned Sparrows have features that are similar to other birds. Here are some similar species:

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) perched on a branch in Manitoba, Canada.

Adult White-crowned Sparrows look crisper overall than adult White-throated Sparrows. White-throated Sparrows have yellow between the eyes and the bill and a bright white throat patch.

Young White-crowned Sparrows have reddish stripes on their crown, while White-throated Sparrows have black lines on the crown.

Additionally, White-throated Sparrows have a white throat patch and a grayish bill.

Golden Crowned Sparrow

Adult Golden-crowned Sparrows don’t have white on the head as White-throated Sparrows do. Additionally, they have a yellow crown stripe.

Young Golden-crowned Sparrows tend to have some yellow on their crowns, which can help us differentiate them from young White-crowned Sparrows. They look very similar.

House Sparrow

Female White-crowned Sparrows are larger, have longer tails, and have larger bills than House Sparrows.

They also have marked faces and white patches on the wings that House Sparrows don’t have.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common are White-crowned Sparrows?

White-crowned Sparrows are a common and widespread bird. Their population has continued to hold steady between the late 1960s and 2019.

Is the White-crowned Sparrow invasive?

No, the White-crowned Sparrow is not an invasive species. It was once thought to be an invasive species, but with archeological records and fossils, it’s been found that these birds have been in North America for at least 3,000 years.

Where do White-crowned Sparrows migrate to?

White-crowned Sparrows are medium-distance migrants and residents in some areas. The birds that breed in arctic Canada and Alaska migrate to many portions of the continental U.S. and Mexico for the winter. Birds that live along the west coast of the U.S. and in parts of the West are year-round residents and don’t migrate.

What does it mean when you see a White-crowned Sparrow?

In general, Sparrows symbolize embracing a simpler life. They’re telling you to focus your energy and time on the things that add value to your life.

Susan

Saturday 5th of August 2023

When I was gardening, I disturbed a white crowned sparrow nest that was built on the ground in one of my flower beds. It had two fledglings in it. The next day the nest was gone. Would the parent birds have dismantled it and moved it somewhere else because I'd disturbed it? I saw no evidence of a cat having gotten the fledglings or destroyed the nest.

Patrick O'Donnell

Wednesday 9th of August 2023

@Susan- How nice to have White-crowned Sparrows nesting in your garden! It's hard to say what happened to it but birds won't dismantle or move their nests.