The Black Tern is small and much darker than other terns. It is very social, often seen migrating in groups, and it tends to nest colonially. Unlike most other terns, the Black Tern eats insects in addition to fish. It is also an inland breeder and migrant, though in the winter it occurs offshore.

Plucking a fish out of the water with your beak is difficult, and Black Terns usually require 3 or 4 tries before they are successful. Insects are easier to catch, and may be caught at a rate of 5 per minute.

On this page

Description of the Black Tern

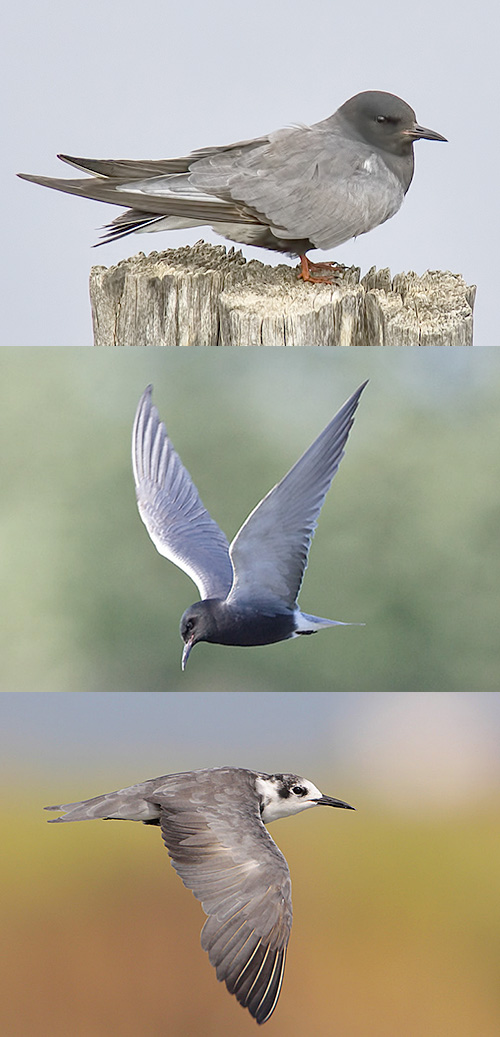

BREEDING MALE

The Black Tern is a small tern which in breeding plumage has a black head and underparts, dark gray wings and upperparts, and a white vent. Length: 10 in. Wingspan: 24 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter adults have a white forehead, nape, and underparts.

Juvenile

Immature birds resemble winter adults, but have faintly barred backs.

Habitat

Black Terns inhabit freshwater marshes and lakes.

Diet

Black Terns eat fish and insects.

Photographs © Greg Lavaty and Glenn Bartley.

Behavior

Black Terns forage by plucking prey from the water’s surface, and by capturing insects in flight.

Range

In North America, Black Terns breed across much of southern Canada and the northern U.S. They winter along the Pacific Coast of Central and South America, and can be seen in migration across most of the U.S. The population is declining.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Black Tern.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

The Black Tern’s choice of habitat changes dramatically with the changing season, from freshwater marshes in the summer to ocean during the winter.

Black Terns breed in colonies, often near Forster’s Terns.

Vocalizations

Common calls include a harsh ‘keef.’

Similar Species

No other common tern species is as dark.

Forster’s Tern

Winter-plumaged Forster’s Terns have dark eye patch and dark tip to the bill. Forster’s Tern has deeply forked tail.

Nesting

The Black Tern’s nest is a platform of vegetation floating in a marsh, or placed on top of a muskrat house.

Number: 2-4 eggs/

Color: Buffy or olive in color with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 21-22 days, and leave the nest in several days, though they associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Black Tern

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Black Tern – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

CHLIDONIAS NIGRA SURINAMENSIS (Gmelin)

A prairie slough, teeming with bird life is one of the most fascinating spots for an ornithologist, for nowhere else can he come in close touch with such a variety of species of interesting birds, with such a multitude of individuals crowded into a narrow space and under such favorable conditions for observation. I have never enjoyed anything more keenly than the long drives we used to take over the virgin prairies of North Dakota, drawn by a lively pair of unshod bronchos, unconfined by fences or roads, with nothing to guide us but the narrow wagon ruts which marked the section lines and served as the only highways. In those days the prairies were like a sea of grass, as boundless as the ocean and nearly as level, where only the distant horizon marked the limit of our view. The prairie birds were interesting but widely scattered over a vast area. In the timber belts along the streams the small land birds were swarming in the only available trees; but the real bird life of the region was to be seen in the thickly populated slough. We seemed to be driving on and on into limitless space until suddenly we came to a depression in the prairie marked by a steep embankment, and there, 10 feet below the level of the prairie, lay a great slough spread out before us. Various ducks – mallards, pintails, shovellers, and blue-winged teal – began rising from the surface as we appeared, and way out in the open water in the center of the slough we could see redheads, canvasbacks, and ruddy ducks swimming about in scattered flocks. An occasional pied-billed or horned grebe and scores of coots were scurrying in and out among the reeds, clucking and scolding or pattering away over the water. Ring-billed and Franklin’s gulls and a few Forster’s terns were floating overhead. The loud cries of marbled godwits, western willets, and killdeers betokened their anxiety as they flew about us. Dainty little Wilson’s phalaropes were flitting about the edges of the marsh, and from the recesses of the reeds came the cackling notes of soras and Virginia rails. Blackbirds, redwings, and yellowheads fairly swarmed in the reeds, and the constant din of their rhythmic notes gave volume to the grand chorus of varied voices that were ringing in our ears. And last but not least, among all this great concourse of bird life, was the subject of this sketch, the black tern, flitting hither and thither, one of the most active and the most restless of the throng.

Nesting: Among all the water birds of the middle west I suppose the black tern is the most widely distributed, the most universally common and the most characteristic summer resident of the sloughs, marshes, and wet meadows of the plains. The center of its abundance seems to be in the great, flat marsh country of Manitoba, where we found it everywhere the commonest and most conspicuous water bird in the extensive cane swamps about Lake Winnipegosis and Waterhen Lake, breeding anywhere in wet marshy situations. In the tall, thick growth of canes (Phragmites comrnunis) their nests were widely scattered and hard to find, but wherever the canes were beaten down or partially open they had placed their frail nests on the dead and fallen canes of the previous year’s growth, and about the little open marshy ponds we found them nesting in small colonies. If we did not find the nests it was not through any fault of the terns, for they did the best they could to show us by their actions where their treasures were hidden. There are few birds that are bolder, more solicitous or more aggressive than these little terns in the defense of their eggs, and even before the eggs are laid they will indicate by their actions the exact locality they have chosen. The short, sharp notes of protest come thicker and faster, as the intruder approaches, and when he is fairly among them their cries are prolonged into hard, shrill, angry screams, as the excited terns dart down upon his head, striking him again and again if he does not retreat. By making use of this telltale habit we were able to locate a number of nests in the hidden recesses of the tall canes, where they were sufficiently open for the bird to drop down upon the nest from above or to rise from it without becoming entangled in the canes. Some of these nests were quite elaborate and well made, resembling miniature nests of Forster’s terns or Franklin’s gulls, but more often they consisted of a few pieces of dead canes or reeds loosely arranged, and sometimes the eggs were laid in a mere depression in the prostrate and closely matted vegetation. In one little open slough hole we found four nests within a radius of 5 yards, but this is closer than they are usually placed. One of these was on the edge of a large muskrat house, just above the water level, and another was built on the remains of an old submerged muskrat nest.

In North Dakota in 1901 we found small colonies of black terns nesting in open situations in the sloughs, where the water was 1 or 2 feet deep and where numerous little piles of dead and partially rotted reeds and flags were floating. The nests were usually very flimsy affairs, a few loosely arranged bits of reeds and flags serving to raise the eggs an inch or so above the water. Often the eggs were laid in slight depressions in this floating rubbish, with no apparent attempt at nest building, where the eggs were wet and nearly awash. In Saskatchewan we found a small colony on June 24, 1906, breeding in a wet, grassy meadow where the water was only a few inches deep. The nests all contained fresh eggs and were merely small piles of rubbish floating among the scattered growth of short green meadow grass. I have several sets of eggs in my collection,’ taken by Mr. Gerald B. Thomas in Livermore, Iowa, during the last week in July. The nests were located in sunken muskrat houses, old grebe nests, and an old coot nest. Nests of the black tern often have substantial foundations of water mosses and other soft vegetable substances, which some writers seem to think are built by the birds. I think, however, that the black tern never gathers any such materials and that these foundations are either old grebes’ nests, or merely floating masses of muck, selected by the terns, on which only the superstructure of the nest is built by them.

Mr. J. C. Knox (1899), who has seen the nest-building process, gives the following account of it:

I had always before believed that the black tern merely hollowed out a nest on a bog and deposited her eggs there, but I was now undeceived. As I was walking along I happened to glance upward and saw .a black tern with something in her bill. She was coming directly toward me, so I dropped down out of sight in a clump of green rushes. Just In front of me was the remains of an old muskrat house, now little more than a bog – a capital place for a tern’s nest. Here she alighted and deposited her weed. stem on the edge of a little hollow near one edge of the bog; then she flew away again, but soon returned with another weed and deposited that. I watched her for half an hour, and during that time she made 14 trips to the nest, bringing material each time, and twice her mate came with her. When I left the nest was not completed, but I think she had quit nest building for that morning. Many of the eggs of this species are laid on a bare bog, with no nest at all, but In this instance a nest was made and the materials, which could have been had directly at hand, were brought from a distance.

Occasionally nests of this species are placed on pieces of driftwood or boards where they are very conspicuous, but usually they are very hard to see, as both nests and eggs match their surroundings perfectly.

Eggs: The eggs of the black tern are very handsome and are subject to considerable variation. Many of these resemble the eggs of some of the Limicolae, as they are often somewhat pointed. The average shape is ovate, with a decided tendency in some specimens toward ovate pyriform. The shell is thin and has a dull luster. The ground color shows a great variety of shades of olive and buff, from “Dresden brown” to “clay color,” and from “deep olive buff” to “ivory yellow.” The eggs are usually heavily marked with the darkest shades of brown, “blackish brown,” “seal brown.” “bister,” and “mummy brown ;” sometimes the eggs are evenly sprinkled all over with fine dots, but more often with larger spots and blotches unevenly arranged. Frequently the markings, of either type, become confluent in a ring around the larger end of the egg, and occasionally large bold markings of different shades of brown produce handsome effects. The measurements of 122 eggs, in the United States National Museum, average 34 by 24 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 37 by 25.5, 35.5 by 26.5, 31.5 by 23 and 32 by 22.5 millimeters.

In the southern portions of its range the black tern apparently raises two broods, at least occasionally, for fresh eggs are frequently found in May and again in July. As very few, if any, of the water birds raise two broods in a season, it may be that these late sets may be second or third layings of pairs previously robbed of their eggs. Some good observers, however, seem to think that two broods are regularly raised in some localities. The full set is almost always three eggs, occasionally two, and very rarely four or even five. Personally I have never seen a set of four eggs, and think it is an exceedingly rare occurrence. Smaller sets than these are probably second layings. Dr. E. W. Nelson, according to Dr. T. S. Roberts (1877), says:

I have seen the eggs of Sterna plum bee deposited on masses of floating weeds in several instances, but only for the third brood, the bird having previously built two nests and deposited the eggs in both, which had been removed by myself to ascertain how many they would lay. The result was almost invariably as follows: First nest, three eggs; second nest, two eggs; and the third, one egg.

Dr. Frank M. Chapman (1904) has learned that the period of incubation is 17 days. Audubon (1840) states that both sexes incubate – a difficult matter to determine, as a black tern is seldom seen on its nest.

Young: The young remain in the nest but a few days, and even before that time they will leave it on the approach of danger. Doctor Chapman (1904) gives an interesting illustration of this in his account of the home life of this species. He says:

Three days later we visited the nest, expecting to see a pair of downy young, but, to our surprise and disappointment, it was deserted. Evidently, however, there was something not far away in which the terns were greatly concerned. With piercing screams they darted at us, once actually hitting Mr. Seton’s hat.

Search failing to reveal any sign of the young birds, the camera was left to play detective. Focusing it on the empty nest and surrounding It with “cattails,” we attached some 70 feet of tubing and retired to the high grasses of a neighboring dry bank. But we were not hidden from the tern. She hovered over us, shrieking her disgust with scarcely a pause, turning her long beak to this side and that, as she brought each eye in turn to hear. Finally, her craik-s grew softer, and, fluttering over the nest, she uttered a soft whcent-checr twheent, which probably meant to her downings “It’s all right; come back home now.” After half a minute of this calling she fluttered lower and dropped out of sight behind the reed barriers. Apparently, there could be little doubt that with her voice she had conjured the chicks back to the nest. Acting on this belief, a dozen rapid strokes were given to the bicycle pump at the end of the tube, and the tern promptly flew up into the air, uttering her loud craik-craik in a way that plainly showed something had happened close by to alarm her, and thus plainly told us that the shutter ca the camera had been sprung. Instantly we rushed through the mud and water to the nest, but only to find it as empty as before.

Inserting a fresh plate in the camera, we returned to our hiding place. Again the tern scolded us vigorously, but after a while, as before, her fears seemed to decrease; she gradually drew nearer to the nest and eventually dropped lightly down into the reeds, evidently on It. After waiting a moment for her to settle herself, the bicycle pump was again used, and at the twelfth plunge of the piston the tern shot upward as though she were blown from the end of the tube. We accepted her action as an unfailing indication that the shutter was properly released and once more splashed quickly through the water to see what we might see; but only an empty nest met our gaze, and we were as ignorant of the fate of the young terns as we had been in the beginning.

The continued anxiety of the parents, however, encouraged us to continue our efforts to solve the mysterious disappearance of their chicks, and, after several more attempts similar to those just related, we reached the nest just In time to see the two little ones paddling away into the surrounding reeds, like ducklings. This caused us to believe that on each occasion they had returned to the nest only to desert it again as the old bird left them; but It was not until the plates were developed, a month later, that we could really put together the whole story.

The young birds are fed by their parents until they are able to fly. Rev. W. F. Henninger writes to me that they seem to be fed on “spiders, water scorpions, flies, and perhaps other swamp-loving insects, fragments of the first three being found in the nests with young.” Mr. Frank M. Woodruff has sent me a photograph showing a black tern alighting on its nest with a large dragon fly in its bill, presumably for its young. The young terns develop very fast and soon learn to fly, but their parents continue to feed them more or less, sitting in long rows on the fences about the marshes or on pieces of drift wood waiting to be fed. Audubon (1840) says that he has “seen the parent birds feed them on the wing in the wanner of swallows.”:

Plumages: The young of the black tern, when first hatched, is a swarthy individual, entirely different from the young of other terns. lit is thickly covered with long, soft, silky down, “cinnamon drab’ on the throat, neck, and sides, shading off to “pale drab gray ” on the belly and cheeks; the upper parts are rich “cinnamon,” heavily blotched with “fuscous black.” When very young the sides of the head, including the orbital region, the cheeks, the lores, and sometimes a narrow frontal strip, are pure white. This feature becomes less conspicuous as the bird grows older. As the bird attains its full size the down is gradually replaced with feathers, beginning on the wings, scapulars, and the sides of the breast; but much of the cinnamon down remains on the head, neck, and crissum until the juvenal plumage replaces it at the flight stage in July. By the time that the young bird has attained its full growth the juvenal plumage has been fully acquired and the flight stage reached. This plumage is worn through August and September, and perhaps later. The upper parts are decidedly brown and often the under parts are extensively washed with brownish, dusky, or drab on the sides of the neck and chest, on the flanks and sometimes on the entire belly. The feathers of the back and scapulars are broadly margined with “clove brown” and narrowly tipped with whitish. The forehead is dirty white, the crown and occiput are mainly black, and the auriculars, as well as a ring around the eye, are pure black. The browns gradually fade and the light edgings wear away during the fall, but there is probably also a partial postjuvenal molt of the contour feathers. The first winter plumage is then much like the adult, but young birds can be recognized by having smaller bills, more or less signs of light edgings in the wing-coverts and back, and tails which are much less deeply forked, the lateral rectrices being broader and more rounded at the tips. I have not been able to trace very clearly the first prenuptial molt, but apparently a majority of the young birds acquire at this molt a plumage which is exactly or nearly like the adult nuptial, with more or less white in the black areas. Many birds, however, seem to wear the first winter plumage or a new one closely resembling it, until the first postnuptial molt, which occurs in June and July. This molt produces the adult winter plumage.

Adults have two complete molts – the prenuptial early in the spring and the postnuptial in July, August, and September. The seasonal change is very striking. In the winter plumage the forehead, a nuchal collar, and the entire under parts are white; the auriculars and a narrow orbital space are black; the crown and occiput are mottled with gray and black; and the mantle, wings, and tail are much lighter gray than in the spring” light neutral gray” or paler.

Food: The black tern is credited with eating minnows or other small fry, but I believe that it rarely does so except when associated with other terns on the coast. Mr. William Brewster (1878) says of their feeding habits in Massachusetts:

They associated most commonly with the Wilson’s and roseate terns, and procured their food in the same way, hovering over the schools of bluefish and pouncing upon the small fry which these voracious creatures drove to the surface. The stomachs of all the specimens which were dissected contained the macerated remains of small fishes only. In no case were any insects detected.

My own experience with the bird in this State is somewhat different, for I have seen large numbers of them hovering over the meadows and grassy marshes, catching insects in the air and darting down to pick them off the tall waving grasses, just as they do in the western sloughs. I have also seen them feeding with the common terns, but I believe that they prefer insect food when they can find it. In the interior the black tern is almost wholly insectivorous; its food includes crayfish, small mollusks, dragon flies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, beetles, spiders, water scorpions, flies, and a great variety of other insects, nearly all of which are caught on the wing. Dr. R. M. Anderson (1907) says:

They evince little fear of man, and large numbers will often follow a man plowing, hovering over his head and looking for grubs turned up by the plow. They are often killed with a whip at such times.

In the South it has been seen capturing the moths of the cottonboll worm in flight over the fields of young plants. Its ability to catch dragon flies, one of the swiftest of insects, is sufficient proof that the black tern is an expert flycatcher. Mr. Ernest E. Thompson (1890) says in regard to this performance:

Besides aquatic insects, the black tern feeds largely on dragon flies, which it adroitly captures on the wing. The bird may frequently be seen dashing about in a zigzag manner so swiftly the eye can offer no explanation of Its motive until, on the resumption of Its ordinary flights, a large dragon fly Is seen hanging from its bill and sufficiently accounts for the erratic movements of the bird. After having captured Its prey in this way I have frequently seen a tern apparently playing with Its victim, letting it go and catching it again, or, If it Is unable to fly, dropping it, and darting under it to seize it again and again before It touches the water.

I have watched black terns for hours beating the air over the western sloughs, dipping down frequently to pick up some small morsel of insect food from the surface of the water, but I have never seen them plunge into the water, as they would do if they were after minnows. They glean much of their food from the tall, waving grasses, reeds, flags, and bullrushes. Their eyes must be very keen to find the small insects and spiders which crawl up the stalks to hide, and they are certainly expert at swooping down and catching them. At certain times, especially when it is blowing hard or raining, countless millions of mosquitoes, flies, small dragon flies, and other small insects seek shelter on the lee sides of the reeds. which means a bountiful harvest for the terns.

Behavior: The black tern is a restless waif of the air, flitting about hither and thither with a wayward, desultory flight, light and buoyant as a butterfly. Its darting zigzag flight as it mounts into the air to chase a fluttering moth is suggestion of a flycatcher or a nighthawk; as it skims swiftly over the surface of the water it reminds me of a swallow; and its true relationship to the terns is shown as it hovers along over the billowy tops of a great sea of tall waving grass, dipping down occasionally to snatch an insect from the slender, swaying tops. When looking for food the bill is usually pointed downward, but in ordinary, flight it points forward. Mr. Thompson (1890) made some calculations as to the speed at which this tern flies and arrived at the following conclusions: A large number of observations resulted in an average of three wing beats per second, with the greatest of regularity; another series of observations, not so satisfactory, allowed a distance of 5 yards to be traversed at each beat. This gave only the disappointing rate of something over 30 miles per hour, but this was at the uncertain foraging flight. Once the mother tern has secured her load of provender a great change takes place, as already mentioned. She rises high in air, and I am sure she doubles her former rate of speed, and straight as a ray of light makes for home. It Is said that many birds can not fly with the wind; not so the tern; for now, if there be a gale blowing her way, she mounts it like a steed and adds its swiftness to her own, till she seems to glance across the sky, and vanishes in the distance with a speed that would leave far behind even the eagle, so long the symbol of all that was dashing and swift.

The ordinary call note of the black tern, given in flight when not particularly disturbed, is a short, sharp, shrill, metallic “krik.” When much excited this is prolonged into a shrill scream like “kreek” or “craik,” given with ear-piercing vehemence when attacking an intruder near its nest. Mr. Henninger, according to Doctol. Chapman (1904), contributed the following interpretation of the notes:

Call note, “kteel”; note of anger and anxiety, “kerr krr”; ordinary note heard while on the wing, “gek.”:

Doctor Chapman described the note used to call the young as a soft “wheent-wheen,t-wheent.”:

With all the varied inhabitants of the sloughs, its bird neighbors, the black tern seems to live in peace and harmony. I have never known it to molest the eggs or young of other species, or to attack the adults, nor can I find in print any evidence of its hostility. It is not as sociable as some other species, and its nests are usually somewhat apart from others. As a species it is sociable and gregarious to a limited extent, and it shares with other terns the habit of gathering in flocks to hover over a fallen companion.

Fall: By the middle or last of August, when the young birds have acquired their first winter plumage and most of the adults have completed their molt, the fall migration begins in a leisurely way, as the birds are in no hurry to reach their winter homes. Their wanderings are more extended at this season and more erratic. Generally a few, and sometimes large numbers, of black terns, mostly in immature plumage, are seen on the Atlantic coast from New England southward, sometimes in large flocks by themselves frequenting the marshes and wet meadows, but more often in small numbers mingled with other terns and gulls along the coast. Rev. M. B. Townsend writes to me that he has seen black terns flying over the waters of the Gulf of Mexico as early as August 1, some of which were still in full spring plumage, some were molting, and some had completed the molt into winter plumage. On June 16, 1910, while cruising off the coast of Louisiana, I saw a large number of black terns in small flocks; I counted 10 of them sitting on a stick of drift timber, equally spaced about a foot apart. They evidently thought that there was no more standing room, for they would not allow another bird to alight on the log, although several tried to do so. Capt. W. M. Sprinkle told me that they breed in the West Indies in February, appear here early in May, and remain all summer. I am more inclined to think that these were nonbreeding birds which failed to migrate northward in the spring.

DISTRIBUTION

Breeding range: Interior of North America. East to eastern Ontario (Kingston and Charleston Lake) and west central New York (Cayuga Lake). South to northern Ohio (Sandusky), northern Indiana (English Lake), northern Illinois (Cook, Putnam, and Henry Counties), central Iowa (Hamilton County), northern Nebraska (Holt and Cherry Counties), north central Colorado (Barr Lake region), north central Utah (Utah Lake), western Nevada (Washoe Lake), and southern California (Elsinore Lake). West to central California (San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys), central southern Oregon (Klamath Lakes), east central Washington (Brook Lake), and central British Columbia (Chilcotin). North in the interior to central Alaska (Fort Yukon), Great Slave Lake, and central Manitoba (Lake Winnipegosis and Lake Winnipeg).

Breeding grounds protected in the following national reservations: In Oregon, Klamath Lake, and Malheur Lake.

Winter range: From the Gulf of Mexico southward to northern South America (Surinam), and along the Pacific coasts of Mexico (Mazatlan), Panama, Peru, and Chile. Nonbreeding and young birds remain in the Gulf of Mexico all summer.

Spring migration: A few birds migrate up the Atlantic coast and across the Great Lakes to the interior. Transient dates: Maryland, May 17 to 30; Pennsylvania, Erie, April 27; New York, Carmel, April 9; Massachusetts, Framingliam, June 20; New Hampshire, Lake Winnipesaukee, June 10. The main flight is northward through the interior. Early dates of arrival: Missouri, St. Louis, April 29; Iowa, Floyd County, March 28; Wisconsin, Mayville, March 22; Minnesota, Heron Lake, May 1; Manitoba, Oak Lake, May 17; Great Slave Lake, Fort Resolution, June 5.

Fall migration: Eastward, at irregular intervals, to the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia southward and then down the coast to its winter range. Transient dates: Prince Edward Island, September 13; Nova Scotia, Sable Island, September 9; Massachusetts, August 7 to September 26; New Jersey, August 4 to October 20; North Carolina, July 28 to September 23; Florida, Tarpon Springs, September 15. Transient dates for the interior: Nebraska, August 8 to October 15; Kansas, July 25 to September 14; Missouri, up to October 21. Pacific coast dates: British Columbia, Sumas, up to September 1; Washington, Bellingham Bay, up to August 26; California, Point Pinos, August 2 to September 23; Lower California, San Jos~ del Cabo, September 6 and 7, and Cape San Lucas, September 16; Mexico, Mazatlan, arrives in October.

Casual records: Accidental in Bermuda (October, 1876). The more northern Atlantic coast records might be classed as casual.

Egg dates: Minnesota and North Dakota: Thirty-six records, May 25 to August 4; eighteen records, June 5 to 13. California: Twenty-six records, May 11 to July 2; thirteen records, May 19 to June 8. Illinois and Iowa: Twenty-four records, May 11 to July 28; twelve records, June 6 to 18. Manitoba and Saskatchewan: Nineteen records, May. 28 to July 5; ten records, June 6 to 14.