Long-tailed Ducks (Clangula hyemalis) are distinctive sea ducks with males having long slender tail feathers extending well beyond their bodies.

They inhabit the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America and come to land only to breed. Here is some more information about those remarkable divers!

On this page

Identification

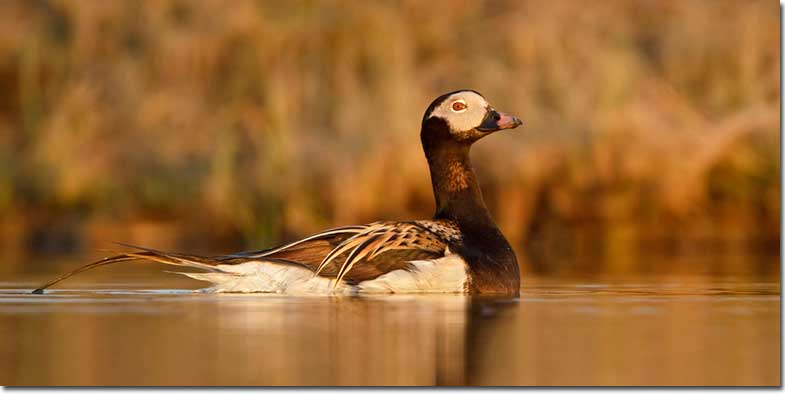

Long-tailed Ducks have a compact and streamlined body, adapted for diving and swimming in marine environments. They are medium-sized, measuring 15-23.5 inches long, with a wingspan of around 28 inches. Both males and females have breeding and non-breeding plumage.

Male

Male Long-tailed Ducks have very long, slender, and distinctive tail feathers. In their breeding plumage, they have a blackish head with a white face patch, dark backs and chests, and white undersides.

Their bills are dark with a pinkish tip. Their non-breeding plumage is almost the opposite. Long-tailed Ducks have a gray face with a white cap and dark cheek patch. Their necks are white, undersides mostly white, chests and upper bellies black, dark brown backs with white plumes, and dark wings.

Female

Female Long-tailed Ducks do not have those long tail feathers. Breeding females are brownish all over with a white collar, white patch behind and around the eye, and pale undersides.

During the non-breeding season, they have paler heads. Their undersides and head are whitish, their back, wings, and breasts are brown, and they have a dark cheek patch and cap. Unlike males, their bills are wholly black.

Vocalizations

Long-tailed Ducks have various distinctive calls from clucking and quacking to growling. During the breeding season, males call with ow-owdle-ow which has a honking and yodeling-like quality to it. Females answer with single calls or growls.

Food

The diet of Long-tailed Ducks primarily consists of aquatic invertebrates and small fish.

Long-tailed Ducks are opportunistic feeders, and their diet varies seasonally due to what’s available.

During the breeding season, their diet focuses on animal matter, including crustaceans, mollusks, insects, insect larvae, fish eggs, small fish, and aquatic invertebrates. In the winter, they also consume plant matter, such as grasses, seeds, algae, and even fruits.

Long-tailed Ducks typically forage during the day by diving underwater to search for food. They are well-adapted for diving, and they can go down to significant depths of up to 200 feet.

Most of their feeding is done 30 feet from the surface. When diving, they keep their wings partly open and use their webbed feet to propel them forward.

Nesting and Eggs

Long-tailed Ducks are monogamous, and some pairs stay together for more than one breeding season. Most pairs form in early spring, but courtship may begin as early as early winter.

Males approach available females with their tails held high and heads low and outstretched over the water. They then raise and lower their heads in a bow and emit those yodeling-like calls. If the female accepts, she will call in response and hold her head close to her body.

After mating, the female leaves the male and chooses a place to nest. Long-tailed Duck nests are on dry ground but close to the water, usually partly concealed by low vegetation or among rocks and often near the nests of other females.

The nest is built into a shallow depression in the ground, lined with leaves, other plant material, and a lot of down feathers from the female.

These ducks raise only one brood per year with 5-11, mostly 6-8 eggs in a clutch. If the first clutch fails, she may try for a second one. Long-tailed Duck eggs are olive to pale gray, measuring 1.9-2.4 inches long and 1.4-1.6 inches wide.

Incubation lasts for 24-29 days, and the female covers the eggs with her down if she needs to leave the nest.

Shortly after hatching, the mother bird leads her offspring to the water. Younglings are responsible for feeding themselves, but the female looks over them and broods them at night. Juvenile Long-tailed Ducks fledge at around 35-40 days after hatching.

Current Situation

Long-tailed Ducks range across the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, Europe, and Asia. In North America, their breeding range includes parts of Alaska and northern Canada, with some populations extending into the northeastern United States and Greenland.

During the non-breeding season, Long-tailed Ducks migrate to more southerly latitudes, where they can be found in coastal areas, estuaries, and open waters.

Long-tailed Ducks’ breeding habitats include tundra regions, coastal areas, and freshwater environments such as ponds and lakes. In the winter, Long-tailed Ducks migrate to more temperate coastal waters, estuaries, and open sea. They can be found in both shallow and deep waters, often diving to considerable depths to forage.

The IUCN Red List lists Long-tailed Ducks as a vulnerable species. Their population is declining due to various factors.

This includes habitat degradation, oil pollution, reduction in food availability, and breeding site destruction. Although this species is not hunted directly, then they are still killed by tens of thousands due to getting stuck in fishing nets.

Facts

- Long-tailed Ducks can dive the deepest and longest out of all duck species. They may go as deep as 200 feet.

- Another name for Long-tailed Ducks was ‘oldsquaw.’

- Long-tailed ducks live for 15 years on average. The oldest individual on record lived for 22 years. However, the road to that age is rough since nesting success is only 30% and only 10% of the ducklings survive until the 30-day mark.

Similar Species

As unique and fabulous as these ducks are, you may still encounter a few fairly similar species. Here are some of the most similar ones and how to tell the difference between them.

Steller’s Eider

Steller’s Eiders have a very limited range in North America and can only be seen around the coasts of Alaska. Males have a cinnamon underside, a black upperside, a white head with a black ring around the eye, a small black patch at the back of the head, a black throat, and white-and-black wings. Females are dark brown and slightly mottled all over.

Males can be distinguished by the fact that Long-tails have long tails, but Steller’s Eiders don’t.

In addition, male Steller’s Eiders have a warm cinnamon underside and dark bills, whereas male Long-tails do not have that kind of color in their plumage, and they have a black-and-pink bill. Female Steller’s Eiders are dark brown overall, whereas female Long-tails have significantly more white on their heads and in their plumage.

Harlequin Duck

Male Harlequins are slaty blue overall with bold white, reddish, and black markings. Females are grayish-brown with paler undersides and white facial markings. Males of the two species are fairly easy to tell apart if you get a closer look.

Male Harlequins lack long tail feathers, but male Long-tailed Ducks do not have red in their plumage. Female Long-tailed Ducks have more white in their plumage than female Harlequin Ducks.

Northern Pintail

Photograph © Sam Crowe.

Northern Pintails have a far wider range which encompasses almost all of North America and extends into Central America. During the breeding season, males have a gray body, a white breast and neck stripe, a brown head, and long tail feathers.

Their non-breeding plumage is almost the same, but their head is gray instead of brown. In flight, you can see a green speculum. Females are mottled brown and white all over with paler undersides.

Males can be distinguished by the fact that male Northern Pintails have a gray body and a brown head instead of a black-and-white body and heads. Female Northern Pintails don’t have white patches on their face like female Long-tailed Ducks do, and they are more uniformly colored and paler overall.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Long-tailed Ducks endangered?

Long-tailed Ducks are listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List due to their declining population.

What is another name for a Long-tailed Duck?

Another name for Long-tailed Ducks is oldsquaw.

Where do Long-tailed Ducks live?

Long-tailed Ducks live in the arctic and subarctic regions, including tundra, coastal areas, and freshwater environments of North America, Europe, and Asia.

What do Long-tailed Ducks eat?

Long-tailed Ducks mostly eat aquatic invertebrates and small fish.