Northern Pintails (Anas acuta) are large dabbling ducks known for their appearance, namely by the pin-like tails in males. They are found across North America, Europe, and Asia and they are highly migratory, able to cover long distances in a surprisingly short time. Here is all you need to know about them!

On this page

Identification

Northern Pintails are large, relatively long and slender ducks, measuring 20-30 inches long with a wingspan of 31-37 inches. They have long and slender necks and pointed wings, making them even more elegant.

Male

Male Northern Pintails are larger than females. Their breeding plumage is an elegant combination of gray, black, white, and brown. They have an overall gray body and wings with a white breast and underside and black rump.

Their head and neck are chestnut-brown and they have a white stripe running along their head and neck to their chest. They have very long black tails and bluish-gray bills. In flight, keep an eye out for their green speculums.

Males, in their non-breeding plumage, look more similar to females. They are pale overall and mottled in dull browns, gray, and white.

Female

Female Northern Pintails are similar to females from other duck species. They are mottled in various shades of brown from pale gray to tan to dark brown. The feathers have a scaly look to them.

Females are paler on the underside and their head is uniformly grayish tan. Their bills are dark gray. Unlike males, females have a dark brown speculum.

Juvenile Northern Pintails resemble the female but are duller, buffier, and don’t look as scaly.

Vocalizations

One of the most recognizable vocalizations of Northern Pintails is a soft, trembling, and high-pitched whistle.

This whistle is often described as proop-proop or like a wheezy train whistle. In addition to the more melodious sounds, Northern Pintails can produce grunt-like calls, most often when they are startled. Females emit quacks similar to that of female Mallards.

Food

Northern Pintails are omnivorous, although the contents of their diet vary from season to season. In fall and winter, they consume mostly plant material, such as seeds, rhizomes, roots, and other parts of grasses, aquatic plants, grains (including rice, barley, wheat, and corn), bulrushes, and pondweeds.

In addition to plant matter, Northern Pintails consume a significant amount of invertebrates, especially during the breeding season. They feed on insects, mollusks, crustaceans, and other small invertebrates found in and around water bodies.

Northern Pintails are dabbling ducks, meaning they feed by tipping forward in the water, reaching for food with their bills, or upending themselves to reach submerged items in shallow water.

They may also forage on land in fields and mudflats, searching for seeds and invertebrates.

Nesting and Eggs

Northern Pintails are monogamous for the breeding season. They are one of the earliest to breed in the spring and start forming pairs even on the wintering grounds.

Males approach a female with their heads down and tails up. Sometimes multiple males follow one female. This may end up as a chase where only one male is left in the end. If the female is interested, they follow the male while clucking, head bobbing, and preening.

Males and females look for a nesting spot together by flying over suitable areas. Northern Pintail nests are built on dry ground in croplands, wet meadows, grasslands, and other similar places among short vegetation. The female builds the nest by scraping a depression into the ground and then lining it with twigs, leaves, grasses, and down feathers.

They only have one brood per year with 3-12, mostly 7-10 eggs in a clutch. Northern Pintail eggs are pale olive and measure 1.9-2.3 inches long and 1.3-1.6 inches wide. Incubation takes 21-25 days.

The young leave the nest within a few hours of hatching with the mother bird leading them to water. Ducklings are responsible for feeding themselves, but the female watches over them and broods them at night. They fledge at around 38-52 days of age.

Current Situation

Northern Pintails are widespread across various regions in the Americas and Palearctic. In North America, their breeding range extends across the northern parts of the United States and Canada. During the non-breeding season, Northern Pintails can be found in more southern areas of the United States, Mexico, and parts of Central America.

Northern Pintails inhabit a variety of open habitats that are near water. They prefer a variety of open wetlands for breeding, including tundra, farmlands, and prairies. During the non-breeding season, they can be found near any areas with shallow water and exposed mudflats, including marshes, lakes, and flooded fields.

Northern Pintails are listed as of least concern on the IUCN Red List. They are common ducks but their population is declining due to loss of habitat and destructive agricultural practices.

Facts

- Northern Pintails are endurable migrants that can fly for 1,800 miles in one go. One individual that was banded in Canada was found in England just nine days later!

- Northern Pintails are also referred to as the northern nomads or the greyhound of the skies.

- The oldest Northern Pintail on record lived to be 22 years and 3 months old. However, their average lifespan is lower since 75% of the hatchlings fledge and only half of them manage to produce offspring of their own.

Similar Species

Male Northern Pintails are fairly unique-looking so identification shouldn’t prove much of a challenge. However, females are a different story. Here is a quick overview of the three most similar species and how to tell the difference.

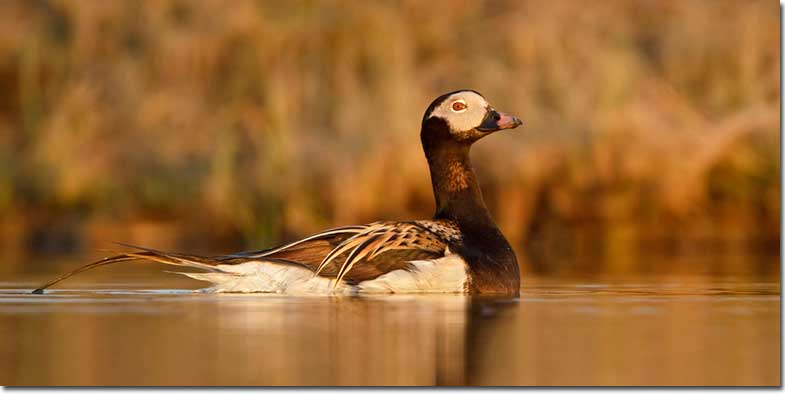

Long-tailed Duck

Long-tailed Ducks range throughout northern North America and aren’t commonly seen in the United States. Breeding males have an overall dark plumage with a white face patch and rump and long black tail feathers. Females are brown overall with variable amounts of white.

Compared to Northern Pintails, Long-tailed Ducks are rather small and have short and triangular-looking bills. Males appear similarly dark at a distance and have long tail feathers. However, male Northern Pintails do not have white face patches and their bodies are gray, not black. Female Northern Pintails are scaly-looking and paler overall whereas female Long-tails are darker and have white patches in their plumage.

Cinnamon Teal

Cinnamon Teals range throughout the western North America. Males are deep brownish-red, and have a brown back, a dark rear, and black bills. Females are mottled in various shades of brown and have a faint dark line through their eyes, a dark cap, and a long black bill.

Males are different but females are fairly similar. However, female Cinnamon Teals are smaller, have a shorter neck, and a longer and flatter bill. They also have a dark cap and line through their eyes whereas female Northern Pintails don’t have that. Female Northern Pintails are paler whereas the female Cinnamon Teal has warmer browns.

Blue-winged Teal

Blue-winged Teals range throughout most of North America. Males have a buff body with dark speckles, a black rear, and a dark bluish-gray head with a white crescent behind their black bills. Females are mottled brown overall, have a dark cap and stripe through their eye, and a black bill.

Again, the identification proves challenging when it comes to females. However, Northern Pintail females are bigger and have longer necks and tails. Female Blue-winged Teals have a dark stripe though their eyes and a dark cap while the Pintail female lacks these features.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where do Northern Pintails live?

Northern Pintails live in a wide range of wetland habitats and open areas near water across North America.

Why are they called pintails?

Northern Pintails are called pintails because of the distinctive elongated central tail feathers of the males, which taper off to a slender pinpoint.

How big are Northern Pintails?

Northern Pintails are large ducks measuring 20-30 inches long.