The Bohemian Waxwing is a very social bird that breeds in remote boreal forests from Alaska, south to British Columbia, northern Washington and Idaho, and east to Manitoba. It occasionally migrates south to California, Colorado, and the northeastern USA.

Named for the red, wax-like tips on their secondaries and their wandering ways, these birds are frequently seen in large flocks of hundreds or even thousands of birds.

On this page

Identification

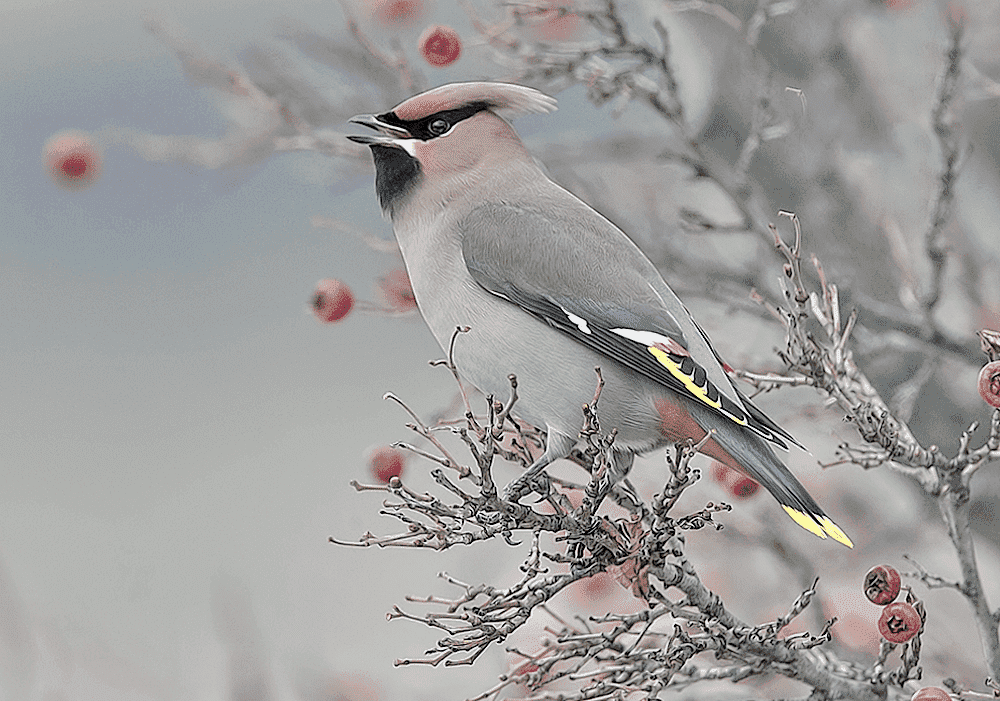

The Bohemian Waxwing is a crested, sleek, starling-sized bird with ashy-gray and brownish plumage and russet highlights on the head. It has a velvet black mask and throat, chestnut under a tail with a bright yellow tip, and a fairly short, black bill with a pale base.

As with other bird species that need to fly long distances, the wings are fairly long. The wings are also blackish, have two small white patches, and show a narrow yellow and white stripe that extends to the tip of the wing when it is closed.

In common with the two other waxwing species (Cedar Waxing and Japanese Waxwing), the Bohemian Waxwing also has tiny red, wax-like tips to some feathers in the wings.

Photograph © Alan Wilson.

Male and female birds are very similar, but females have a bit less black on the throat and have smaller and fewer wax tips on the wings. Juveniles are grayer overall, lack the black throat, have a shorter crest, no red tips on the wings, and have dusky streaking on whitish underparts.

In flight, the long, pointed wings and rather short tails of Bohemian Waxwings can give them a compact, starling-like appearance, and like that bird, they also fly in tight flocks.

However, the yellow tip on the tail of the Bohemian Waxwing is prominent, and the chestnut vent and white in the wings are usually visible.

Although this species does not have an actual song, it is very vocal and frequently makes staccato, trilling calls.

Food

The Bohemian Waxwing feeds on ripe berries and fruits, and small insects. It can also take tree sap and flower buds but mostly eats fruits like mulberries, honeysuckle, blackberries, cherries, and Mountain Ash berries.

During the winter, this species will also feed on apples, grapes, Russian Olive fruits, and Cedar berries.

This species finds fruiting trees by wandering in flocks to locate food sources and then feeding until they have eaten most or all of the available fruit. The birds then move on in search of other fruiting trees, often flying long distances in the process. This beautiful bird of cold winter scenes forages on fruits by picking them while perched or in hovering flight.

© Alan D. Wilson

Bohemian Waxwings also take a variety of small insects. Waxwings catch bugs by picking them from leaves and bark while perched and during dramatic sallies to catch insects in flight, especially over rivers, ponds, and other bodies of waters.

Insect prey items can include everything from mosquitoes to dragonflies, beetles, and caddisflies. These are mostly caught during the summer in the boreal forests where Bohemian Waxwings breed.

In winter, depending on the availability of fruiting trees, they can wander south of their normal range in search of food, even entering orchards and neighborhoods planted with ornamental, berry laden bushes and trees.

Nesting and Eggs

In June, the male and female Bohemian Waxwing build a cup-shaped nest located anywhere from three to 20 feet up in the fork of a conifer or other tree near a beaver pond, river, other wetland, or in an area that had been burned.

The nest is constructed with twigs taken from conifers like spruce and tamarack, and is lined with cocoons, grasses, and other soft materials.

The female arranges most of the nesting material to shape the nest to her liking and also camouflages it with moss and lichen. In doing so, she hangs bit of vegetation from the nest to help it blend in with other parts of the tree.

Building the nest takes around three to five days. The nest has a diameter of six to seven and a half inches and an inside depth of one and a half to three inches.

Bohemian Waxwing lays a clutch of four to six, pale blue eggs with some black and gray spotting, mostly at the larger end of the egg.

Eggs weigh around 3.8 grams each on average and hatch after around two weeks. Both adults feed the young a variety of regurgitated fruit, buds, and insects, and the young leave the nest after 18 days.

These fledged young continue to be fed by their parents for two weeks or more, and when they can fly, flock with their parents and other adult and juvenile Bohemian Waxwings.

Current Situation

Bohemian Waxwings breed in boreal forests from Alaska and western Canada east to Manitoba and south to northern Washington and Idaho. In winter, they move around in search of fruiting trees in southern Alaska and western Canada south to California, Colorado, southern Canada, and east to Nova Scotia and Maine.

© Alan D. Wilson

This species also breeds in northern Scandinavia and in a large area of Russia and winters south to China, Japan, Central Asia, and central and eastern Europe. Some birds also migrate to Britain, some years seeing more individuals than others.

This species is fairly common, at least in its remote breeding and wintering range and is not endangered.

It is less frequently seen south of its regular winter range, but in years when fruit crops are scarce in the north, large numbers can show up in other, more southerly parts of its distribution.

The Bohemian Waxwing doesn’t face many threats but can be affected by pesticide spraying of fruiting trees, and is also susceptible to being hit by cars when foraging in roadside shrubs and trees.

Although it still occurs in fairly large numbers, for unknown reasons, the Bohemian Waxwing is one of several common birds believed to be in decline and is therefore being closely monitored by ornithologists.

Facts

- The Bohemian Waxwing is monogamous, but unlike many bird species, it doesn’t have a set territory. This is probably because it relies on fruit food sources that can be abundant but that also occur in random places over a large area.

- The red and yellow coloration in the Bohemian Waxwing are carotenoid pigments that come from its food sources. If this bird did not eat red fruits and berries, it might not have any red or yellow highlights.

- In some parts of its range, flocks of the Bohemian Waxwing can number in the 100s and even the 1000s! Such flocks can be joined by Cedar Waxwings and thrushes that also feed on fruit. Once such flock in 1908 was so big, it was noted as being 200 to 300 feet wide and taking a full two to three minutes to pass overhead!

- In some parts of Europe in the past, the arrival of Bohemian Waxwings coincided with outbreaks of cholera and other diseases. For this reason, they were sometimes referred to as “plague birds” and in the hope of gaining protection, people ate some of the same berries as the waxwings did.

Similar Species

Bohemian Waxwing is a distinctive bird easily identified in most parts of its range. However, it does resemble another related and more familiar species, the Cedar Waxwing.

Cedar Waxwing

The Cedar Waxwing has a very similar shape but is smaller, has yellow on the belly, and has more of a warmer brown coloration than the gray of the Bohemian.

They also lack the white patches in the wings and the chestnut vent of the Bohemian Waxwing.

Both birds are known for their distinctive silky plumage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Bohemian Waxwings rare?

Bohemian Waxwings are not rare. Still, they are difficult to see south and outside of their regular distribution in Canada and the northern USA.

Where do Bohemian Waxwings live?

Bohemian Waxwings live in boreal forests from Alaska south to northern Washington and Idaho, and east across Canada to Manitoba. In winter, they can also occur in much of southern Canada, and can show up in the western and northern USA.

What is the difference between Bohemian Waxwing and Cedar Waxwing?

Bohemian Waxwings are larger than Cedar Waxwings, are grayer in coloration, have more black on the throat, more white in the wing, and have chestnut under the tail. They also lack the yellow shown on the belly of the Cedar Waxwing.

Why are Bohemian Waxwings called Bohemian?

Bohemian Waxwings are called “Bohemian” because they wander over large areas in search of food.