The Allen’s Hummingbird (Selasphorus sasin) is a colorful hummingbird species found along the West Coast of the United States.

These tiny wonders are known for their vibrant plumage and catch attention with intricate courtship displays. However, since they look quite similar to Rufous Hummingbirds, it is important to know what exactly they’re like.

On this page

Identification

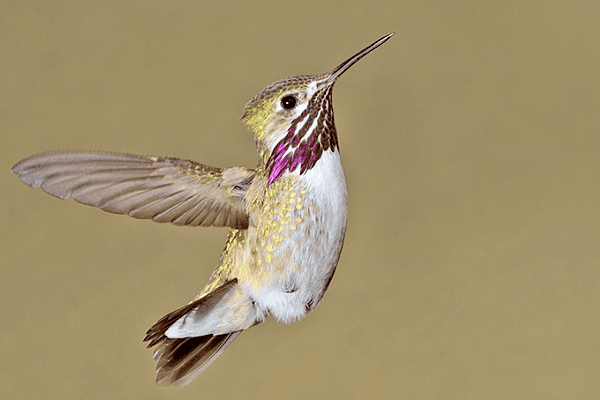

Allen’s Hummingbirds are compact and small, measuring only 3-3.5 inches in length with a wingspan of 4.3 inches. Their black bill is slender and straight, slightly longer than their head. Their wingtips do not extend past tail feathers when the bird is perching.

Male Allen’s Hummingbirds’ plumage is a striking combination of primarily iridescent green and coppery orange colors. Their back, crown, and the top of their head are a brilliant metallic green.

Related: Birds with orange chests

They have a white collar and rust-colored rump, tail feathers, and flanks. Their most distinctive feature is their radiant, fiery orange-red throat. Depending on the angle of light, this throat patch can appear black.

Females have duller plumage

Female Allen’s Hummingbirds look similar to males, but they are duller, have more green in their plumage, and lack the iridescent orange throat patch. Instead of the throat patch, they have iridescent spots.

Juvenile Allen’s Hummingbirds look similar to females.

Vocalizations

Allen’s Hummingbird call is a sharp high-pitched chip or tick. They also produce a series of rapid, high-pitched chattering sounds, buzzing calls, and soft, somewhat melancholy-sounding whistles.

Food

Allen’s Hummingbird’s diet consists of nectar and insects. They need to feed approximately every ten to fifteen minutes and prefer red flowers. Some favorite flowers include red columbine, scarlet sage, penstemon, red monkeyflower, currant, ceanothus, twinflower, gooseberry, and manzanita.

In addition to the nectar they get from flowers, they catch small insects like small beetles, tiny wasps, flies, and ants for protein.

Allen’s Hummingbirds have long, slender bills with tubular, grooved tongues that are perfectly adapted for sipping nectar from flowers.

They hover in front of flowers and insert their bills deep into the flowers to reach the nectar hidden within. Insects are caught mid-air or by gleaning them from leaves and branches. They also visit hummingbird feeders for sugar water.

Nesting and Eggs

Male and female Allen’s Hummingbirds have separate territories. As the breeding season begins, the female starts to visit the territories of different males.

Males put on J-shaped aerial displays where they fly high up, dive back down, and then fly back and forth in a pendulum-like way, making a buzzing sound. The male mates with the female and then returns to his territory. One male may mate with many females.

Allen’s Hummingbirds nest is generally 2-50 feet above the ground on a horizontal or diagonal branch in a tree or shrub. It is cup-shaped and constructed of fine plant fibers and moss, lined with plant down, and camouflaged with lichen pieces. It also contains spider silk, so it can expand as the clutch grows.

This hummingbird species may have up to 3 broods in a season with 2 white eggs per clutch. Allen’s Hummingbird eggs are only 0.5-0.6 inches long and 0.3-0.4 inches wide.

The female incubates the eggs for 17-22 days and protects and feeds the nestlings until they leave at about 22 days after hatching. They are immediately independent after leaving the nest. The male doesn’t contribute at all.

Current Situation

Allen’s Hummingbirds range along the western coast of the United States from southern California to southern Oregon. They migrate to central Mexico for the winter. One subspecies is resident year-round and can be found in California’s Channel Islands and some parts of the nearby mainland.

Allen’s Hummingbird habitats are often semi-open and brushy areas. During the breeding season, they can be found in streamside groves, city parks, well-wooded suburbs, open oak woods, scrub, and chaparral.

Females prefer more forested areas, whereas males can be found in more open areas.

In Mexico, they inhabit foothills and mountain forests. During migration, you may meet them in high mountain meadows.

Allen’s Hummingbird is listed as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List. They’re fairly common throughout their range but their numbers have been in a decline because this species is not as adaptable to urban environments.

Facts

- The ability to hover and fly backward is unique to hummingbirds and they require a lot of energy to do so. Allen’s Hummingbirds need to consume nectar or other food every 10-15 minutes to keep their energy levels up and they may visit around 1000 flowers each day!

- Allen’s Hummingbird may hybridize with other hummingbird species, including Anna’s Hummingbird and Rufous Hummingbird. The hybrid of Anna’s is called the Floresi’s Hummingbird.

- Allen’s Hummingbirds are highly territorial. Females defend their nests and offspring very fiercely, and males may even chase away aerial predators much larger than them, such as hawks and kestrels.

- At night, Allen’s Hummingbirds are in a state of torpor, which lowers their heart rate and metabolism speed. They perch on a branch in what may look like a lifeless state, but worry not! Once the sun rises, they will wake up and start moving again.

- The average lifespan of Allen’s Hummingbird is about 2 years. The oldest recorded individual, however, was at least about 6 years old.

Similar Species

Allen’s Hummingbirds are similar to some other hummingbird species. We have introduced 3 of them and how to tell them apart.

Rufous Hummingbird

Males are quite similar, but Allen’s Hummingbirds have a green back, whereas Rufous Hummingbirds do not. However, sometimes they may have some green as well.

If their tails are spread out, then you can tell them apart by their outermost tail feathers. Allen’s are narrow, whereas Rufous’ feathers are broad.

Females and immatures are very difficult to identify in the field as they look almost identical. The only way to do so is to look at their outermost tail feathers, the same way as with males.

Broad-tailed Hummingbird

Female and immature Broad-tailed Hummingbirds may be confused for female or immature Allen’s Hummingbirds.

However, Allen’s Hummingbirds have a rust-colored tail whereas Broad-tailed Hummingbirds do not. Broad-tailed Hummingbirds also have a broader tail and are generally a bit larger.

Calliope Hummingbird

Photograph © Alan Wilson.

Female and immature Calliope Hummingbirds are a bit similar to female and immature Allen’s Hummingbirds due to their green crowns and backs. However, Calliope Hummingbirds are smaller, have a green tail, and their wingtips are about the same length as their tail.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called Allen’s Hummingbird?

Allen’s Hummingbird is named after their discoverer, an American taxidermist and collector Charles Andrew Allen.

Are Allen’s Hummingbirds rare?

Allen’s Hummingbird is numerous within its range, but it is quite uncommon to actually spot them.

What is the difference between Allen and Rufous Hummingbird?

Allen’s Hummingbird’s outermost tail feathers are narrow, whereas Rufous Hummingbird’s ones are broad. Male Rufous Hummingbirds generally also have an orange back, but some may also have a green back, which confuses things. Females and immatures of the species are almost identical.

Where do Allen’s Hummingbirds live?

Allen’s Hummingbirds live in the semi-open brushy areas from coastal California to coastal Oregon.