The large sea duck known as the White-winged Scoter in North America for the large, obvious patches of white in its wings is known as the Velvet Scoter in Europe, for the satiny-black plumage of the males. White-winged Scoters migrate mostly by day over land, but may travel either at night or by day over water.

White-winged Scoters typically begin breeding at age two or three. Females often return to the same general breeding area in subsequent nesting seasons. Gulls are major predators of young chicks, but those that survive may live a long time. The oldest known White-winged Scoter lived over 18 years in the wild.

Length: 21 inches, Wing span: 33 inches

Description of the White-winged Scoter

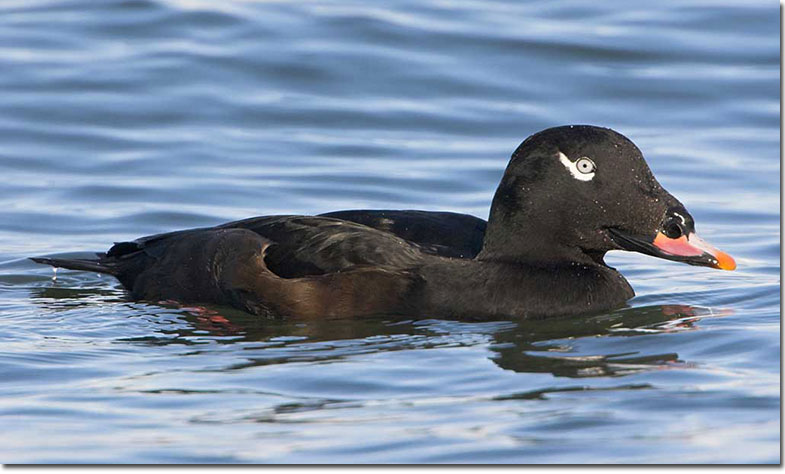

Breeding Male

Adult male. This photograph clearly shows the multi-colored bill with the knob at the base. The Nike Swoosh around the eye is diagnostic. Photograph by Glenn Bartley.

Photograph © Glenn Bartley

The White-winged Scoter is a large sea duck with a large bill and rounded forehead, and white secondaries that are visible both in flight and as a small white patch while swimming.

Male/breeding plumage:

– Black plumage with brownish flanks.

– Reddish bill with a black knob at the base.

– White patch below and behind the eye.

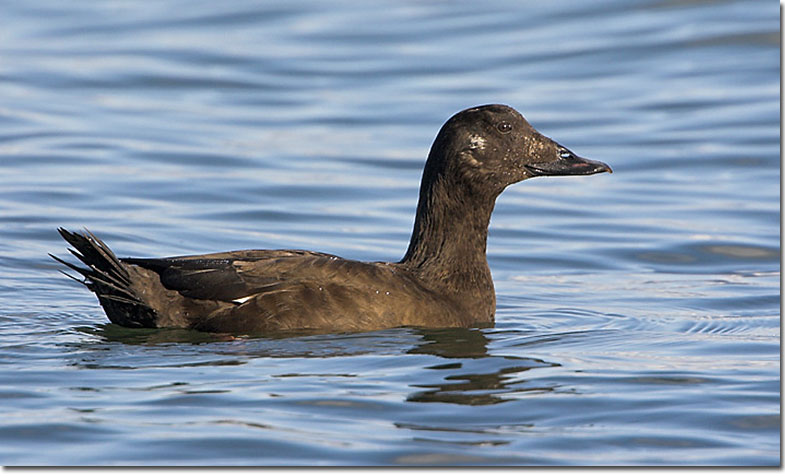

Female

Adult female. Amount of white on the face variable. The head is generally a uniform black with the white cheek patch. The females of the other two scoter species have the appearance of a dark crown contrasting with a lighter face. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

First winter female. The amount of white on the head is variable. Adult females generally show less white on the head. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

The small oval white patch on the base of the bill and the hint of white on the cheek are indicative of adult female White-winged Scoter. In winter, scoters are sometimes seen some distance off shore. The distance and bobbing in the waves can make identification very difficult. Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

-Brown plumage.

-Whitish area between eye and bill.

Seasonal change in appearance

White area at eye of male can be less obvious in spring and early summer.

Juvenile

Juveniles resemble adult females but have two prominent white patches on the head.

Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

The center bird has the uniformly dark head of an adult White-winged Scoter. But what about the other two birds? The bill shape and color say scoter but which one? First winter females of both Surf and White-winged Scoters have 2 white face patches that vary in size and shape and are very similar in appearance.

And all three scoter species can be found in mixed flocks. There are subtle differences in head and bill shape but it takes a lot of experience to tell them apart when the birds are far away and moving up and down with the waves.

Habitat

Lakes, oceans, and bays.

Diet

Mollusks, crustaceans, and aquatic insects.

Behavior

Forages by diving.

Range

Breeds in Alaska and northwestern Canada, as well as parts of eastern Canada. Winters along the east and west coasts of the U.S. and Canada.

Fun Facts

While White-winged Scoters have a few displays that are performed during the breeding season, other scoter species are more display oriented.

White-winged Scoters reach their breeding grounds and begin nesting later than most ducks.

Vocalizations

Generally silent. Will make soft squeeks.

Similar Species

Adult Surf Scoters of either gender have more white in the head and larger bills. Black Scoters are smaller with a more rounded head shape.

Surf Scoter

Nesting

The nest is a down-lined depression.

Number: 9-10.

Color: Buff.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at 25-30 days.

– Young fledge (leave the nest) shortly after hatching but remain with the female for some time.

Quess:

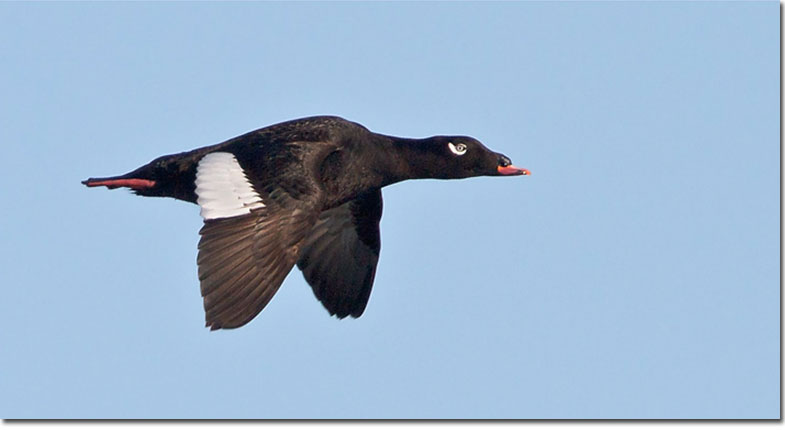

Adult female. Wing linings pale. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

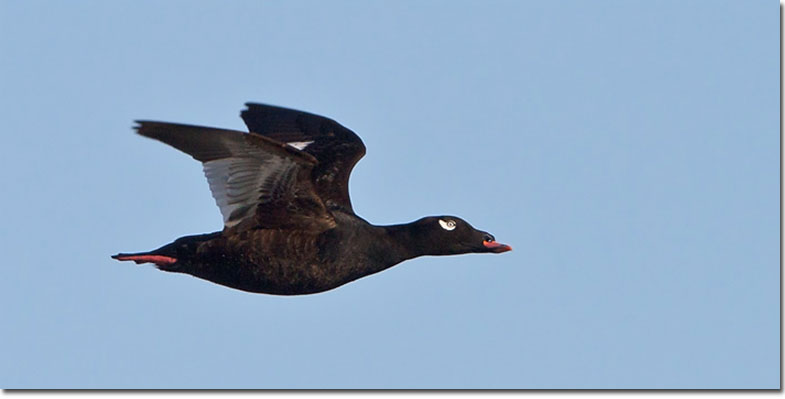

The white wing patch is distinctive and present on all ages on both males and females. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

In poor lighting conditions the white secondaries may appear dark. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

The white wing patch and overall shape of this bird identifies it as a White-winged Scoter. Photograph © Greg Lavaty.