The exceptionally long migration of the White-rumped Sandpiper is something that is hard for earth-bound humans to comprehend. Single flights lasting over forty hours and covering a distance of some 2,500 miles are not unusual. Significant weight gains are needed before such flights, making food-rich stopover sites a critical part of the White-rumped Sandpiper’s ecology.

Male White-rumped Sandpipers defend a territory only long enough for courtship and egg laying, and then they abandon the territory and nest. Little is known about the frequency of returning to the same breeding territory each year, but some banded individuals have returned to the same wintering territory in subsequent years.

On this page

Description of the White-rumped Sandpiper

BREEDING MALE

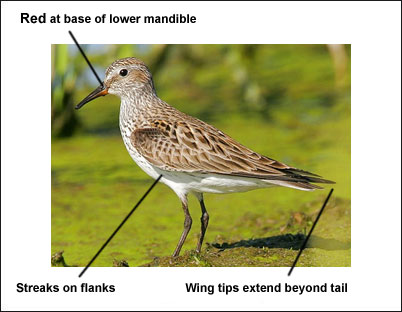

The White-rumped Sandpiper is a small shorebird with dark legs and a mostly dark, slightly drooping bill with a pale base. Breeding birds have streaked flanks and some rufous on the upperparts. In flight, a white rump and white wing stripes are visible. The wing tips extend beyond the tail on standing birds. Length: 7 in. Wingspan: 17 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds are plainer and mostly gray above.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to breeding adults, but have broad white feather edgings on the upperparts.

Habitat

White-rumped Sandpipers inhabit mudflats, flooded fields, marshes, and tundra.

Diet

White-rumped Sandpipers eat insects, mollusks, and seeds.

Behavior

White-rumped Sandpipers forage by gleaning from the surface of the ground or by probing in mud.

Range

White-rumped Sandpipers breed in arctic Canada and Alaska. They winter in South America, and occur across the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. in migration. The population is stable.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the White-rumped Sandpiper.

Fun Facts

White-rumped Sandpipers migrate from Canada to southern South America each year, and are a late spring migrant in the U.S., occurring in large flocks in the central U.S.

As with many shorebirds, White-rumped Sandpipers need high quality stopover habitat to refuel during their long migrations.

Vocalizations

The flight song is very high and insect like. A squeaky call is also given.

Similar Species

- Baird’s Sandpiper

Baird’s Sandpipers do not have white rumps, and they have a less pronounced supercilium. Other small Calidris Sandpipers have wing tips that do not reach the tail tip on standing birds.

Photograph© Greg Lavaty.

Nesting

The White-rumped Sandpiper’s nest is a depression lined with moss and leaves, and is surrounded by grass or moss.

Number: Usually lay 4 eggs.

Color: Olive with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 22 days, and leave the nest shortly after hatching, though associating with the female for some time.

Bent Life History of the White-rumped Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the White-rumped Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

PISOBIA FUSCICOLLIS (Vieillot)

The white-rumped, or Bonaparte, sandpiper is a great traveller; it breeds in a limited area on the Arctic coast of North America and winters in extreme southern South America.

Spring: From its winter home in South America, this sandpiper makes an early start; Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) writes:

At Guamini, Buenos Aires, from March 3 to 8, white-rumped sandpipers were encountered in northward migration from a winter range In Patagonia. The species was fairly common on March 3 and increased greatly in abundance on the two days that followed. The northward journey was apparently as concerted as the movement that carried the birds southward, as on March 6 there was a noticeable decrease In their numbers, and by March 8, though the birds were still common, the bulk of Individuals had passed. They arrived in flocks from the southward, often of several hundred Individuals, that whirled in and circled back and forth along the lake shore to decoy to birds feeding on the strand or to rise again and continue swiftly northward. Those that paused kept up a busy search for food along the muddy beaches In or near shallow water, or in company with little parties of buff-breasted sandpipers on the drier alkaline flats back of the shore line. In early morning they were especially active and were in continual movement. Occasionally they worked out into comparatively deep water where in feeding it Is necessary to Immerse the head over the eyes nearly to the ear openings. When disturbed flocks rose with soft notes that resembled tseet tseet or tseup to circle to new feeding grounds on the lake shore.

The spring migration route is apparently northward along the Atlantic coast of South America and through the West Indies to the United States. Only a few migrate along our Atlantic coast., as the main flight is northward through the interior, during May and the first few days of June. Many reach their breeding grounds before the end of May.

Courtship: Doctor Wetmore (1926) gives an attractive account of what seems to be a beginning of courtship in Argentina; he writes:

Occasional parties of males, animated by the approaching breeding season, broke into soft songs and called and twittered, often for several minutes, in a musical chorus in low tones that had so little carrying power that they merged in the strong.wind, and it was some time before I succeeded In picking out the sweet individual songs tsep a tsep a tsep a or twee twee tee tee ty tee given as the head was bobbed rapidly up and down. Occasionally when the fall sunlight came warmly I sat in the mud and let little hands of white rumps work up around me until they were feeding and calling within a meter or so, eyeing me sharply for any cause of alarm. At such times their twittering choruses came sweetly and pleasantly, clearly audible above the lap of waves and the rush of the inevitable winds of the pampas. Between songs the search for food continued without cessation. At short Intervals, activated by the warmth of the sun, they suddenly indulged in dozens of combats with their fellows, bloodless nifrays, of bluff and retreat, where they lowered their heads and with open mouths ran Rt one another pugnaciously. The one attacked sidled qnickly away or fluttered off for a short distance, save where two of equal temperament chanced to clash when first one and then the other threatened with raised wings In alternate advance and retreat until the fray was concluded to their mutual satisfaction. At such times the movements of these otherwise plain little birds were sprightly and vivacious to a degree. Their loquacity at this season was marked as it contrasted strikingly with their silence and quiet during the resting period of southern summer. Flocks frequently rose to perform intricate evolutions and then returned with a rush to sweep along the shore and join less ambitious comrades. As they passed the white rump flashed plainly, certain advertisement of the species. At times the chattering of these active flocks reminded me of the twittering of swallows.

J. Dewey Soper found this Species quite common at various places on Baffin Island, and has sent me some very full notes on it, from which I quote as follows:

The species was encountered at Nettilling Lake, June 10. 192~, when a mated pair was flushed from a marshy upland near the Takuirbing River. The sexual organs in both were fully developed, the female being almost on the point of laying. By the 14th the species had become quite common. The moles practised their vocal performance on the wing immediately upon arrival. They rise to a height of about 61) feet above the tundra and there they hover with rapidly beating wings giving utterance to their nuptial song in notes so weak that when a wind Is blowing nothing may be heard of It even at comparatively close range. It is given in a very low tone and slow tempo; the notes are weak and Inclined to be squeaky, with a weird dripping quality like the sound of water oozing and dropping in a small cavern. The species appears to flush silently.

Nesting: Very little seems to be known and still less has been published about the nesting habits of the white-rumped sandpiper. In MacFarlane’s notes I find brief records of seven nests found by his party on the barren grounds and Arctic coast of Canada, from 1862 to 1865. One nest was found on June 21, 1862, 50 miles east of Fort Anderson; the female and three eggs were taken; the nest consisted of a few leaves in a small hole in the ground near a small lake. Another found on June 29, 1863, on the barren grounds, is described as “a mere depression in the ground lined with a few decayed leaves~~ the female and four eggs were taken. There is a set of four eggs in the Herbert Massey collection, taken with the parent bird by E. A. Mclllhenny at Point Barrow, Alaska, on June 25, 1898; the nest is described as “a hollow in the moss on top of a ridge on the tundra, lined with dry grass and partly arched over.” This is farther west than the species is supposed to breed, but there are several birds in the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences collected there in June, which are in full breeding plumage.

Mr. Soper found a number of nests near Nettilling Lake, Baflin Island, on which he has sent me the following notes:

A nest containing four eggs was found on a grassy hummock on the tundra bordering the lake on June 16. Many were subsequently found. The nest is merely a shallow depression on the crown of a tussock of grass and mosses a few inches above the surrounding mud and water of the tundra. It is sparingly lined with blades of old grass and dead leaves of the dwarf arctic willow. Some are lined exclusIvely wIth the dried, oval leaves of Salia, 1&erbacea. According to collecting data, both sexes arrive together, with the female almost, if not Quite, ready for immediate reproduction, as evidenced by the condition of the ovaries. The nest of four eggs found on June 16 was but four days after the first observed arrivals of the species.

The female upon one’s approach plays the familiar artifice of simulating a prostrated condition, limping and dragging herself along the ground in an effort to attract one’s attention from the nest. In this they are bold and fearless; and when one sits beside the nest they will frequently run up to within a foot or less of the observer. In photographing nests from a distance of only a few feet, the female will often return to her eggs while one’s head Is under the dark cloth adjusting the focus. One was so devoted to her eggs that she would run up and peck at my fingers and run over my hnnd as I extended it toward the nest. This species, when one approaches the nest, usually leaves It when one is 20 to 25 yards distant and runs along the ground, either directly toward the Intruder or a little to one side. Because of its remarkable similarity to the covering of the tundra at this time, this first movement often escapes one, and consequently when the bird is first observed fluttering along the ground one naturally imagines himself near the nest, when, In reality, it may he 20 or 30 yards away. This ruse is a clever one, and no doubt would often save the nest from violation. The nests are easily found by retiring and watching the female with the glasses. They usually return to the nest with little artifice or delay; in fact, often within two or three minutes. The ahove procedure is not an invariable practice, as one female I knew would flush directly from the nest to begin her tactics only when there was danger of the nest being actually trodden upon.

Eggs: The four eggs usually laid by the white-rumped sandpiper are ovate pyriform in shape; all that I have seen are uniform in shape and have characteristic colors and markings. One of the two sets in the United States National Museum has a “deep olive buff” ground color, and the eggs are heavily blotched about the larger end, sparingly spotted elsewhere with “wood brown,” “warm sepia,” and “benzo brown,” and with a few underlying spots of various shades of “brownish drab”; an egg from this set is well figured by Frank Poynting (1895). The other set differs from this one in having the ground color lighter, “olive buff,” and the spots finer, more scrawly, and lighter in color; the underlying drab markings are also more numerous.

There is also a set of four eggs in the Thayer collection, taken with the parent bird by Alfred II. Anderson on Taylor Island, Victoria Land, July 7, 1919. These eggs are much like the egg figured by Mr. Poynting, except that in one or two of the eggs the ground color is more greenish.

One of the three sets taken by J. Dewey Soper on Baffin Island looks much like a miniature set of long-billed curlew’s eggs. In three of the eggs the ground color is “mignonette green,” covered with small spots, more thickly at the larger end, of “bister” and “snuff brown “; the other has a “deep lichen green” ground color and is irregularly blotched near the larger end, finely speckled elsewhere with “bistei” and “brownish drab.”

The measurements of 34 eggs average 33.7 by 24 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 36.1 by 23.6, 34.2 by 27.7, 31.5 by 23.5, and 35 by 22.8 millimeters.

Young: Mr. Soper’s notes on the young are as follows:

The first juveniles, ahout a day old, were seen and collected on July 11. They were exceedingly active, a good example of precocial young. These were ashy below, huffy above, with black markings, and the down over the lower back and rump tipped with small spots of white. This species is much more demonstrative and less artful in the concealment of young than Baird’s sandpiper. The adults come within a few feet of the intruder, and by their action advertise much more clearly the position of the young. The parent birds keep up a continual fine twittering cry of alarm, the female louder and more pronounced. The male comes on the scene only at intervals with a mouselike squeaking note. The young are adepts in the art of concealment, “freezing” fiat to the ground with warning notes from the adults. They will lie in this fashion as though daad until actually picked up in the hand. When they realize the game is up they then become wild and frantically struggle to escape. When allowed to do so they will run rapidly away and either hide again or attempt to reach tbe mother bird, whose frantic cries come from but a few yards away.

A young white rump about two-thirds grown and almost on the point of flight was captured on August 1. Others seen a fe~v days later on the shore of Kuksunlttuk Bay were capable of short flights. As an experiment, I tried several times to keep individual young alive at my base tent on the Takuirbing River, but they Invariably died within about 24 hours regardless of the best care.

Plumages: The downy young white rumped is much like the downy young of other tundra nesting species of sandpipers. From the stilt sandpiper it can be distinguished by its much shorter legs and shorter and slenderer bill, from the Baird by its more huffy face and breast, these parts being pure white in baird-i, and from the least by paler and duller browns in the upper parts and by white, instead of huffy terminal tuft spots. The crown, back, rump, wings, and thighs are variegated or marbled with “Sanford’s brown,” or “tawny,”‘ and black, dotted, except on the front half of the crown, which is mainly bright brown, with whitish terminal tufts. The forehead, a broad superciliary stripe, the sides of the head, throat, and breast are pale buff or buffy white; the remaining under parts are grayish white. A median frontal stripe of black terminates in “tawny” toward the bill; there are extensive black areas on either side of the crown and on the occiput. The nape is grizzly, buff, gray and dusky.

In juvenal plumage the crown is sepia with “tawny” edgings; the back, rump, tertials, and scapulars are sepia, with “tawny” edges, and some of the feathers of the mantle and scapulars are also white tipped; the under parts are white, but the breast is suffused with light buff and narrowly streaked with dusky; the median and lesser wing coverts are broadly edged with light buff or whitish.

The postjuvenal molt of the body plumage usually occurs in September and October, mainly in the latter month, but sometimes not until November. The upper body plumage is not all molted, so that first winter birds can be distinguished by tawny or huffy edged feathers in the mantle and by the juvenal wing coverts. The next partial prenuptial molt apparently removes all traces of immaturity.

Adults have a prenuptial molt, beginning in March, of the underbody plumage, most of the tipper-body plumage, sometimes the tail, and some of the wing coverts. But this is almost immediately preceded by the delayed molt of the remniges in January and February, so that it seems to be a nearly complete prenuptial molt, which is barely finished before the birds start on their long northward migration. The postnuptial molt of adults, beginning in August and often lasting into October, involves only the body plumage, the tail, and some scapulars, tertials, and wing coverts. The gray winter plumage, so different from the brightly colored spring plumage, is seldom seen in its completeness before the birds go south.

Food: Very little seems to have been published on the food of the white-rumped sandpiper, but W. L. McAtee (1911) gives it credit for eating some injurious insects and worms, such as grassï hoppers, the clover-root curculio, which is injurious to clover, and ï marine worms (Nereis), which prey on oysters.

Stuart T. Danforth (1925) says that four collected in Porto Rico: had eaten 77.7 per cent of animal food and 22.3 per cent of vegetable matter.

Fifty per cent of the animal matter consisted of blOodworms, 25 per cent of Planorbis snails, and 5 per cent of Corira reticulata. The vegetable matter consisted entirely of seeds, of which those of Compositae formed 33.3 per cent, Seabaet emeruR 30 per cent, and Perstearia portoricensi.s 36.7 per cent. In addi tion to food, the stomachs contained mineral matter (coarse red sand) forming 32.5 per cent of the stomach contents.

Behavior: Lucien M. Turner, who has had abundant opportunity to observe this species in Ungava, writes in his notes:

The flight of these birds is remarkably firm and swift, generally in an undulatory manner nnd swerving to the right or left often with the body Inclined to one side, the wing nearly perpendicnlar, alternately presenting the upper and lower surface of the body. Just before alighting the wings are raIsed until the tips nearly tonch over the back and for a moment held outstretched and then slowly folded, The bird is quite active while searching for food and seldom remains more than a few seconds in a spot, where It constantly picks here and there for the minute organisms which form Its food. During this time all Is activity and quite in contrast to the interval while the tide Is high and the bird is on the high land resting and digesting Its food. Here It is more sleepy and less easily disturbed. The eyesight of these sandpipers is certainly very acute, as they nre able to detect the presence of a person at a long distance and give a twittering, snipey note, other wise regardless of approaching danger. In all their doings the utmost harmony seems to prevail. The only object of their lives seems to be to gather food.

No sooner does the water begin to ebb than a few of these birds will swish over some point of land with merry twittering, eagerly scanning the bank for the least appearance of mud now being exposed. By the time the tide has half ebbed myriads of these birds are sweeping back and forth along the river. As the water shallows over well known bars, and scarcely has the water shoaled enough to permit the birds to alight without swimming, than as many sanfipipers as can collect on the place eagerly alight and begin probing the ooze for food. The lowering water is followed by the thronging birds to the last Inch.

The flowing tide begins and the btrds retreat carefully seizing every object of food that the rising Water brings to the surface. Often they are so eager In their search that many birds are crowded into tile deeper water and save themselves only by flight. This or that place is quickly covered over by the water and again the birds collect into larger flocks which now sway to the right or left, alternately, exposing their silvery white underparts which gleam In the sunshine like a stream of silver. The gray or brown of their backs relieving the color as the long stream of birds pass by. They partially halt their fight and become a compact flock, whereupon they separate Into smaller flocks which, as the water gradually rises and covers their feeding grounds, now betake themselves to the higher lands of the banks above.

Here, around the pools on the highlands, or among the grassy margins of the lakes, they collect to wash themselves and digest the food they have obtained from the salt-water mud.

As a person approaches one of these pools, in the latter part of August, little suspecting that anything will be found near them, these birds turn their backs, which so closely resemble the lichen covered granite as to render the birds indistinguishable. A nearer approach and they present their white breasts which afford a striking contrast with the surroundings. In a moment they run together and huddle into a compact flock before they take wing. I have, by firing at the proper moment, secured every individual composing a flock of over a dozen birds. If they fly they take to their wings with a sudden impulse and fly in a zigzag movement for a few yards then swerve to right or left continuing until another locality is reached, where they sit quietly until approached. This is repeated every tide and, as the birds are crepuscular also in their habits, their opportunities for becoming fat are nearly doubled. They acquire the fat in a short time. The thickness of the layer is often one-fourth of an inch and completely envelope the body. The least abrasion of the skin or a shot hole soon fills the surrounding parts with oil which has exuded from the wound, making the preparation of skins for specimens a very difficult matter. The flesh of these birds is peculiarly tender and richly flavored. At times I have gone out to shoot these birds for the table and with five discharges (of half an ounce of No. 12 shot) I secured on one occasion 82 birds. A heavy stick thrown in among them as they wade along the water’s edge also knocks many of them over, for these birds seem so intent on procuring food that but little heed is given to the hunter.

William Brewster (1925) says:

Invariably among the tamest and most confiding of our so-called shore birds, they will usually permit one to approach, either on foot or in a boat, within 5 or 6 yards, while I have known a gun to be discharged into a flock with fatal effect, but without causing any of the birds which escaped injury to take wing. Like most obese creatures they are habitually sluggish, confining their wanderings afoot to limited areas, and exploiting these very deliberately, walking slowly and sedately in crouching attitudes, with measured steps, frequently stopping to thrust their bills listlessly a little way into the soft ground, or to pick up small morsels of food from the surface. Occasionally, however, one may see them running to and fro over the mud quite briskly and ceaselessly, perhaps incited to this comparatively unusual behavior by the example of other waders feeding close about them, for they are by no means averse to the companionship of several of the lesser kinds, such as semi. palmated plover and sandpipers, grass-birds, dunlins, etc. Although somewhat loath to take wing, even when threatened by obvious danger, they are likely to fly swiftly arid far, when once started, doubling and circling over the marshes in much the same manner as other small sandpipers.

John T. Nichols, says in his notes:

When startled, a bird has been seen to crouch down concealing the hulk of its white underparts and practically disappear against the brightly lighted mud flat on which it had been feeding. This is a habit shared by Its close relatives the pectoral and least sandpipers.

Voice: The white-rumped sandpiper is ordinarily a rather silent bird, but its short, sharp flight note is characteristic of the species and serves to distinguish it readily in the field. To me it sounds like tzeep or tzip; Mr. Nichols calls it “a squeaky mouse-like fret “; Mr. Brewster (1925) describes it as” a feeble lisping zip or trip, fringilline, rather than limicoline, in character “; and Doctor Townsend (1905) thinks that “it suggests at times the call note of the pipit.” C. .1 Maynard (1896) refers to “one cry in particular, being loudly given and greatly prolonged, resembling the scream of a rapacious bird more than the whistle of a sandpiper.”

Field marks: The best field mark for this species is the white rump, or rather upper tail-coverts; this is conspicuous in flight but is usually concealed by the wings when the bird is on the ground. I have noticed that, while the bird is standing with its side toward me, the gray of the upper parts extend down on the sides of the neck as far as the bend of the wing, whereas in the semipalmated sandpiper, with which it might be confused, there is a decided white space in front of the wing.

Mr. Nichols says in his notes:

This bird is a size larger than least or semipalmated sandpipers, and at favorable angles shows a diagnostic white patch crossing above the rather dark tall. This white patch is a good example of color which apparently functions as a recognition mark. If the same were fortuitous one would not expect the fall to he darker than in related species, as Is the case, causing the white rump to show morn prominently. Straight bill, (or with slight decurviture at the tip, like that of the pectoral sandpiper) and as a rule finely and sharply streaked head and breast prevent chance of confusion with the European curlew sandpiper, of casual occurrence on our Atlantic coast.

Fall: The beginning of the fall flight is apparently southeastward from its breeding grounds xvest of hudson Bay and perhaps southward from Baflin Island, where it breeds. Mr. Turner’s Ungava notes give a very good idea of this first step in the migration and a good impression of the great abundance of this species; he writes:

As I proceeded farther northward I did not observe a single one of these sandpipers until we came to anchor off the mouth of Georges River (July 31) where quite a number were seen on the pebbly beach, seeking their food among the rocks and shingle as the tide receded. At this date quite a number, In fact fully three-fourths, of those seen were birds of the year as was fully attested by traces of downy plumage yet among the feathers of the body and especially on the head and neck. The sizes of the flocks varied from three or four to nearly a dozen, doubtless consisting of a single brood or, in the case of the larger flocks, of two or more broods with their parents. Some of the younger members of the flocks had time wing quills not fully developed while others were considerably farther advanced. Such a variation of plumage both in age and coloration was exhibited that I presumed there must be two weeks difference In the ages of the different young.

By the 10th of August all the young are well able to fly anti make protraded flights in search of food. By this date they assemble in flocks, amount three at times, to thousands of individuals, resorting to the mud flats left bare by the receding tide. The mouth of the Koksoak and the cove to the westward of it present excellent tracts of mud deposited in the little indentations. By the middle of September these birds begin to depart to the south. Many of them ascended the Koksoak and others doubtless followed the windings of the coast down the Atlantic. I have seen numerous flocks over a hundred miles from the mouth of the river as late as October 12th, and an occasional single bird as late as the 20th of that month. I have observed, at the mouth of the Koksoak River, flocks of these birds often numbering over a hundred individuals suddenly appear from high in the air. These I suspected to be birds coming from the regions to the northward of the strait for they always came from the sea.

Thence there is an overland flight to the Atlantic coast. Mr. Brewster (1925) says:

White-rumped sandpipers visit Lake Umbagog regularly and not infrequently, if rather sparingly, in autumn, appearing oftenest during the month of October. Those arriving early in the season are mostly adult birds which occur singly or two or three together; those coming later are of various ages and sometimes in flocks containing as many as eight or nine members each, but rarely, if ever, a greater number. Bonaparte’s sandpipers are hardy birds. They may be seen at the lake when its bordering marshes are stiff with frost. Once (October 26, 1883) I found nine of them near the mouth of Cambridge River two days after the entire region had been covered with snow to a depth of 7 inches.

This bird is a regular, but never an abundant, migrant on the coast of Massachusetts in the fall. The vast numbers which Turner saw in Ungava must seek some other route; the species is never abundant in the interior in the fall and it seems to be rather rare on the Atlantic coast south of New England; the natural inference is that it migrates at sea from Maine or Nova Scotia directly to South America or the West Indies. It is abundant at times in Bermuda.

The adults begin to reach Cape Cod in August, but the main flight comes in September, consisting partially of young birds; most of the young birds come in October and some linger as late as November 10. While with us the white-rumped sandpiper frequents the wet meadows and marshes near the shore, as well as the sand flats, mud flats, and beaches, feeding at low tide singly or in small flocks and usually associated with pectoral, semipalmated, or least sandpipers. During high tides, while the flats are covered, this species may be seen on the high sandy beaches, mixed in with the vast flocks of small shorebirds, sleeping, or resting, or preening their plumage, while waiting for feeding time to come again; if the wind is blowing, all the birds are facing it; many are crouching on the sand and others are standing on one leg with the bill tucked under the scapulars. These flocks often contain hundreds and sometimes thousands of birds, mainly semipalmated sandpipers, semipalmated plover, and sanderlings. They are not all asleep, however, for if approached too closely, they all rise and whirl away in a vast shimmering cloud, flashing now white and now dark as they turn, and settle on the beach again at no great distance.

Winter: August finds the white-rumped sandpiper migrating along the coast of Brazil and it has been known to reach Cape Horn as eady as September 9. Doctor Wetmore (1926) writes:

The white-rumped sandpiper was the most abundant of the migrant shore birds in the regions visited In southern South America. The species was not recorded until September 0, 1920, when it appeared In abundance in southward migration on the lagoons at kilometer SO, west of Puerto Pinasco, Paraguay. The first flocks from which specimens were taken were adult females, and two taken on the date when they were first recorded had laid eggs a few weeks previous as was shown by the appearance of the ovaries. The southward migration came with a rush as the birds passed through the night as witnessed by their calls. The flight continued until September 21, when a dozen, the last seen here, were recorded. The birds circled about lagoons in small compact flocks or walked along on muddy shores, where they fed with head down, probing rapidly in the soft mud; anything edible encountered was seized and swallowed and the bird continued without delay in Its search for more.

Farther south this species was encountered In abundance in Its winter range on the pampa. Ten were recorded at Dolores, Buenos Aires, October 21, and from October 22 to November 15 the species was found in numbers on the coastal mud flats on the Bay of Samborombom. A few were seen at pools of water in the sand dunes below Cape San Antonio. Along the Rio Ajo whiterumped sandpipers were encountered in flocks of hundreds that came upstream to search the mud flats at low tide or were concentrated on bars at the mouth when the water was high. In early morning there was a steady eight of them passing to suitable feeding grounds. The birds flew swiftly, with soft notes, from 3 to 15 feet from the earth. In feeding they scattered out In little groups that covered the bare mud systematically. It was not unusual to record as many as 2,000 In a day. About two hundred were observed in the bay at Ingenlero White, the pert of Bahia Blanca, on December 13, and at Carhue, Buenos. Aires, from December 16 to 18, whlte-rumped sandpipers were noted in fair numbers on inundated ground back of the shore of Lake Epiquen or about fresh-water ponds on the pampa inland. None were found In Uruguay during February.

Ernest Gibson (1920) says of this species, at Cape San Antonio, Buenos Aires:

This Is certainly our commonest wader, and is found everywhere in flocks, from, say, the end of October to the middle or end of March. The number In these gatherings Is only restricted by the area of the feeding ground; hence, when large mud flats are available In the vicinity of our fresh or salt water lagunas and cangrejales, or at the subsidence of a flood, the flocks are sometimes of enormous size. The observer may see many acres of ground which look to be In continuous movement, the surface being alive with the restless throng of sandpipers running about and chasing each other, feeding, or taking constant short flights.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: North and South America; casual in Europe.

Breeding range: Ahhough the white-rumped sandpiper has been noted in summer from Wainwright, Alaska, east to southern Greenland (Julianshaab), the only places where eggs have been taken are Point Barrow, Alaska; Herschel Island, Yukon; Taylor Island, Victoria Land; Fort Anderson and Rendezvous Lake, Mackenzie; and the southeast shore of Lake Nettilling, Baffin Island.

Winter range: North to Paraguay (Rio Pilcomayo and Rio Parana); and Uruguay (Montevideo). East to Uruguay (Montevideo) ; Argentina (La Plata, Cape San Antonio, Bahia Bianca, Rio Chubut, and Puerto San Julian); the Falkiand Islands; and Tierra del Fuego. South to Tierra Fuego; and southern Chile (Straits of Magellan). West to Chile (Straits of Magellan and Santiago); and Paraguay (Rio Pilcomayo).

Spring migratin: Early dates of spring arrival are: Florida, De Funiak Springs, May 12; Georgia, Savannah, May 17; South Carolina, Mount Pleasant, May 7, Frogmore, May 7, and Charleston, May 16; North Carolina, Cape Hatteras, May 2, Churchs Island May 6, and Pea and Brodie Islands, May 15; Virginia, Smith’s Island, May 14; District of Columbia, Washington, May 11; New Jersey, Long Beach, May 9, Trenton, May 12, and Bernardsville, May 14; New York, Mastic, May 11, Canandaigua, May 19, Rockaway Beach, May 21, and Freeport, May 22; Connecticut, Middletown, May 10, and New Haven, May 19; Rhode Island, Block Island, May 16; Massachusetts, Melrose, May 9, and Harvard, May 20; Vermont, Woodstock, May 14, Brattleboro, May 18, and Rutland, May 19; Maine, Scarboro, May 29; Quebec, Godhout, May 24, and Quebec City, May 27; Louisiana, Lobdell, May 14; Kentucky, Bowling Green, April 27; Missouri, Jacks Fork, May 15, and Sand Ridge, May 16; Illinois, De KaIb, May 8, and Elgin, May 11; Ohio, Canton, May 8, Berlin Center, May 11, and Youngstown, May 17; Michigan, Detroit, May 6; Ontario, Toronto, May 26; Iowa, Marshalltown, May 4, and Sioux City, May 7; Wisconsin, Whitewater, April 28; Minnesota, Wilder, May 5, Jackson, May 13, and Heron Lake, May 19; Texas, Brownsville, April 11, and Ingram, May 8; Kansas, Emporia, May 4, Lawrence, May 5, and Topeka, May 7; Nebraska, Neligh, May 1, and Peru, May 13; South Dakota, Sioux Falls, May 5, and Vermilion, May 9; Manitoba, Whitewater Lake, May 12; Saskatchewan, Ravenscrag, May 13; and Mackenzie, Fort Resolution, May 19, and Fort Simpson, May 26.

Late dates of spring departure from the wintering grounds are: Argentina, French Bay, March 7, and Guamini, March 8. In North America, late dates are: South Carolina, Mount Pleasant, May 30, and Frogmore, May 31; North Carolina, Raleigh, May 24, and Lake Ellis, June 15; Virginia, Smith’s Island, June 7; Delaware, Lewes, June 8; Pennsylvania, Erie, June 4; New Jersey, Bernardsville, May 24, and Camden, May 24; New York, Castlcton, June 2, and Long Beach, June 20; Massachusetts, Harvard, June 4; Illinois, Waukegan, June 9; Ohio, Painesville, June 14, and Lakeside, June 25; Ontario, Toronto, June 21; Iowa, Sioux City, May 30, and Keokuk, June 5; Wisconsin, Madison, May 30; Minnesota, Hallock, June 8; Texas, Lomita. May 22., and Gainesville, May 24; Kansas, Fort Riley, May 22 and Stafford County, June 6; Nebraska, Lincoln, May 20, Republican Fork, May 25, and Valentine, May 25; South Dakota, Forestburg, May 27, and Vermilion, June 5; North Dakota, Charlson, June 1; Manitoba, Reaburn, June 6, Duck Mountain, June 8, and Shoal Lake, June 20; and Saskatchewan, Kutanajan Lake, June 9, and Quill Lake, June 10.

Fall migration: Early fall arrivals are: Saskatchewan, Indian Head, July 1; Texas, Tivoli, August 17; Minnesota, St. Vincent, August 4; Wisconsin, Lake Koshkonong, August 1; Iowa, 1~4a rshalltown, August 19, and Keokuk, August 21; Ontario, Toronto, August 23; Michigan, Lansing, July 29; Massachusetts, Marthas Vineyard, July 16, and Ipswich, July 24; Rhode Island, Providence, July 18, and Block Island, July 27; New York, Orient, July 24; New Jersey, Long Beach, July 7; Pennsylvania, Erie, August 29; Florida, Palma Sola, August 2?~; Paraguay, hear Puerto Pinasco, September 6; and Patagonia, Orange Bay, September 9.

Late departures in the fall are: Mackenzie, Slave River, October 1; Saskatchewan, Eastend, September 12; Manitoba, Shoal Lake, September 21; Minnesota, Hallock, October 16; Iowa, Marshalltown, November 7; Ontario, Toronto, November 2, and Ottawa, November 5; Ohio, Columbus, October 28, and North Lima, October 29; Ungava, Koksoak River, October 20; Baffin Island, Pangnirtung Fiord, September 25; Labrador, Battle Harbor, October 29; and Quebec, Montreal, October 31; Maine, Lake Umbagog, October 14, and Bangor, October 23; Massachusetts, Lynn, October 12, Boston, October 22, Harvard, October 24, and Cape Cod, November 10; Connecticut, Branford, October 23, and East Hartford, October 30; New York, Ithaca, October 16, Quogue, October 30, Shinnecock Bay, October 30, Oneida Lake, November 3, and Canandaigua, November 4; Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, October 10, and Erie, October 29; District of Columbia, Anacostia, October 24; Virginia, Lake Drummond, November 5; Ohio, Columbus, November 15; North Carolina, Church’s Island, October 7, and Raleigh, December 7; South Carolina, Mount Pleasant, October 17, and Frog. more, October 24; Georgia, Savannah, October 9; and Florida, St. Augustine, December 2.

Casual records: Although probably on the migrational highway, records of the white-rumped sandpiper in Central America, the West Indies, and Lesser Antilles are so few that in these places it can only be considered as a casual visitor. Specimens are in the British Museum from Lion Hill, Panama; Momotombo, Nicaragua; and Tizimin and Cozumel Island, Mexico. It also has been observed or taken on the islands of Barbados (September 20 and 22, year i); Dominica (November 5, 1904); St. Lucia; Guadeloupe; Martinique; Trinidad; Porto Rico (Mayaguez, October 2, 1900, andï Culebrita, April 15, 1912); Cuba; the Bahamas (Inagua, May 27, 1879, and. Fortune Island, August 5, 1876); and the B’~rmuda Islands. Examples were reported from the Yellowstone River, Montana, August 8 to 13, 1878; it has been taken at Laramie, Wyo.; in New Mexico (Fort Fillmore, October, 1852, and Zuni Mountains, September 16, 1851); and there are several records for eastern Colorado. The specimen reported from Oakland. Calif., was probably the Pectoral sandpiper, P. maculata. One was taken at Hopedale, Labrador.

White-ruinped sandpipers have been reported in the British Isles fourteen or fifteen times and a specimen was taken in Franz Josef Land on June 28 (year unknown, but prior to 1898).

Egg dates: Arctic Canada: 14 records, June 15 to July 24; 7 reccords, June 30 to July 12. Alaska: 2 records, June 25.