Baird’s Sandpipers complete a very long migration each year. From their breeding range in northernmost North America to their wintering area as far south as southernmost South America, some Baird’s Sandpipers migrate more than 9,000 miles in just 5 weeks.

Upon arriving on her breeding grounds, a female Baird’s Sparrows lays her 4 eggs in about 4 days, and the weight of this clutch of eggs is greater than her own body weight. This amazing feat of rapid nesting and large eggs helps guarantee that a brood can be raised before the very short arctic summer ends.

On this page

Description of the Baird’s Sandpiper

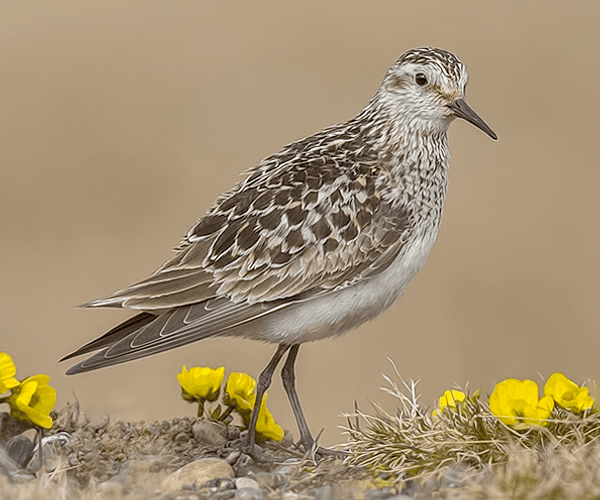

BREEDING MALE

The Baird’s Sandpiper is a small shorebird with dark legs and a dark bill. Breeding birds are grayish-brown above with large black spots. In flight, a white wing stripe is visible. The wing tips extend beyond the tail on standing birds. Length 7 in. Wingspan: 17 in.

Non-breeding plumage below.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds are plainer and mostly grayish-brown above.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to breeding adults, but have broad white feather edgings on the upperparts and a buffy breastband.

Habitat

Baird’s Sandpipers inhabit mudflats, fields, and tundra.

Diet

Baird’s Sandpipers eat insects.

Behavior

Baird’s Sandpipers forage by gleaning from the surface of the ground.

Photograph © Alan Wilson.

Range

Baird’s Sandpipers breed in arctic Canada and Alaska. They winter in South America, and occur across central portions of the U.S. in migration. The population is stable.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Baird’s Sparrow.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

- Juvenile, Washington, Aug. (missing innermost primary)

- From belo

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

Baird’s Sandpipers migrate from Canada to southern South America each year, stopping in drier habitats than most other shorebirds along the way.

Juvenile Baird’s Sandpipers migrate south more slowly and later in the season than adults.

Vocalizations

The flight song is a buzzy rattle. A “kreep” flight call is also given.

Similar Species

White-rumped Sandpiper

White-rumped Sandpipers have white rumps, and they have a more pronounced supercilium.

Western Sandpiper

Wing tips shorter than tail on Western Sandpiper, longer on Baird’s. Breeding Western has more rufous markings.

Nesting

The Baird’s Sandpiper’s nest is a depression lined with lichens and grass, and is surrounded by grass.

Number: 4.

color: Buffy in color with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 19-22 days, and leave the nest shortly after hatching, though associating with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Baird’s Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Baird’s Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

PISOBIA BAIRDI (Coues)

Spring: This sandpiper belongs to that class of birds which Abel Chapman (1924) 50 aptly terms “globe spanners,” for on its migrations its traverses the whole length of both American continents twice a year. From its wintering grounds in Patagonia it must start north even earlier than the preceding species or else it must travel faster. Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) observed it migrating past Buenos Aires on March 5 in company with whiterumped sandpipers, and it has been known to reach Texas early in March. From there its course seems to be northward between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. A. G. Lawrence tells me that it passes through Manitoba between April 28 and May 29; and J. A. Munro gives me, as his spring dates for southern British Columbia, April 30 to May 10. Prof. William Rowan (Mss.) calls it extremely abundant in Alberta about the middle of May and usually gone by the 24th. It is very rare east of the Mississippi in the spring. E. A. Preble (1908) saw large flocks foraging on floating ice at Lake Athabaska on May 25. Dr. Joseph Grinnell (1900) records it at the Kowak River, Alaska, on May 20. Joseph Dixon (1917) says:

On May 31, 1914, at Grimn Point, Arctic Alaska, the first pair of Baird sandpipers for the season were noted feeding along the rim of a frozen tundra pond. The weather had turned bitterly cold during the previous night, and as a result the newly formed ice on the ponds was thick enough to support a man. Strictly speaking, there was no night at this date, for the two months of continuous daylight had already begun; so In a short time the sandpipers were hustling about picking up the mosquito and other pupae which were being washed out by a newly-born stream that gurgled under the snow and Ice on its way down to the frozen lagoon.

Courtship: Two somewhat different accounts of the courtship of this species have been published. IV. Sprague Brooks (1915), who found this bird breeding at Demarcation Point, Alaska, writes:

Only once did I note any courtship activity. On this occasion (May 24), the male would fly a few feet above the female, while she rested on the ground, with quick erratic wing strokes suggesting a nighthawk. Frequently he would alight and raise the wings high over the hack as a gull does before folding them. Then with the forearms perpendicular, the primaries would he slowly raised and lowered like a pump handle, generally lowered to right angles with the forearms, sometimes lower. Not a sound was uttered.

Alfred M. Bailey (1926), whose observations were made at Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, says:

Cutting down the opposite side of the ridge, I heard many calls which reminded me of home in the early spring, for the combined totals sounded like the singing of many little grass frogs in a meadow pond. It was the call, or rather the “spring song,” of the Baird sandpiper. I soon flushed a little female, which fluttered away uttering cries of alarm. I concealed myself, and she soon returned, the male also hoverIng about, making his little froglike peep. At times he would rise high in the air, in the way so characteristic of male sandpipers, give forth his song, and sail down to perch.

Nesting: MacFarlane’s notes mention seven nests found in the vicinity of Franklin Bay, but very few data were given; “on June 24, 1864, a nest containing four eggs was found in the Barren Grounds, in a swampy tract between two small lakes, and was composed of a few decayed leaves placed in a small cavity or depression in the ground, shaded by a tuft of grass.” John Murdoch (1885) says:

The nest was always well hidden in the grass and never placed in marshy ground or on the hare black parts of tundra, and consists merely of a slight depression in the ground, thinly lined with dried grass. All the eggs we found were obtained from the last week in June to the first week of July, a trifle later than the other waders. The sitting female when disfnrbed exhibits the greatest solicitude, running about with drooping, outspread wings, and loud outcry, and uses every possible wile to attract the intruder from the eggs. The nest is so well concealed and forms so inconspicuous an object that the only practical way to secure the eggs is to withdraw to one side and allow the sitting bird to return, carefully marking where she alights. Having done this on one occasion and failing to find the eggs, after flushing the bird two or three times I discovered that I had walked on the eggs, though I had been looking for them most carefully.

Mr. Brooks (1915) writes:

Two nests were found, each containing four eggs and about one quarter incubated on June 12 and 14, 1914. Murdoch found them nesting rather later than other waders at Point Barrow, but my experience at Demarcation Point was quite the opposite, for here they were the first to breed. A female taken June 2, bad a fully formed and colored egg about ready to lay. Both of the above nests were on dry, well-drained tundra near the bases of knolls. The nests were like the other sandplpvrs, and lined with dry willow leaves, but the cavities were less deep than those of the semipalmated sandpiper.

The female was on one nest and the male on the other. The former left the nest when I was some distance away and flying directly toward me alighted within a few feet. While I was at the nest she walked hurriedly about close by constantly uttering a plaintive weet-wect-weet always repeated three times. Occasionally she would take a short flight about me and utter a note very simliar to the rattling call of the pectoral sandpiper. The male when disturbed acted quite differently. He sat closer and on leaving the nest showed the greatest concern, dragging a “broken” wing in the most distressing manner. In neither case was the mate about as frequently occurs with the semipalmated sandpiper.

Mr. Dixon (1917) says:

At Griffin Point. less than 50 miles to the eastward of Demarcation Point, the first set of eggs (fresh) was taken on June 24. The last set was found July 11, with the four eggs nearly ready to hatch. Murdoch speaks of the nests being well concealed and always hidden in the grass. In those nests which we found, no attempt had been made at such concealment, as they were placed absolutely in the open, with nothing to cover or conceal the eggs at all, and the nests so shallow that the tops of the eggs were almost or quite level with the surroundln~ grass. Far from being conspicuously exposed thereby, however, the eggs were shielded from discovery in the most effective manner possible, for in color and markings they blended so perfectly with the brown tundra that a person could easily look directly at them from a distance of 6 feet and still not be able to see them.

This method of nesting seems to he the most effective way of escaping one great danger at least, namely, the notice of the countless jaegers, both parasitic and pomarine. These robbers subsist almost entirely during the breeding period on the young and eggs of other birds, and cruise continually back and forth over the sandpipers’ nesting ground, looking for the least telltale feather, bit of wind-blown down, or other object which might afford a clue to the whereabouts of a nest.

Herbert IV. Brandt found only one nest of the Baird sandpiper near looper Bay, Alaska, which he tells me: Was on a dry mossy ridge amid the dunes and was partially concealed by the surrounding curly grass. It was flimsily constructed of grass stems and filled with a scant handful of small leaves of the dwarf birch and blueberry, together with a few adjacent reindeer-moss stems. The measurements of this nest were: Inside diameter 2y2 inches, and depth perhaps 2 inches.

Eggs: The Baird sandpiper lays ordinarily four eggs, occasionally only three. These vary in shape from ovate or ovate pyriform to subovate, and they have a slight gloss. In color they often resemble certain types of western sandpipers’ eggs, as they are usually of a decidedly reddish tone; but they are considerably larger. The ground color varies from “pinkish buff” to “pale pinkish buff ” or from “olive buff” to “cartridge buff.” Three quite different types are represented in my collection. In the western sandpiper type the “pinkish buff” ground color is quite evenly covered over the whole egg with small, elongated spots, somewhat thicker at the larger end and having a spiral tendency, of “Hay’s russet” and “chestnut brown,” with a few underlying spots of “brownish drab.” Another set has a “cartridge buff ” ground color, which is unevenly covered, chiefly at the larger end, with small spots of duller browns, “bister,” “Saccardo’s umber,” and light shades of “brownish drab.” This seems to be the commonest type. An unusually beautiful set has a “pinkish buff” ground color, sparingly sprinkled with minute brown dots and boldly blotched with great, irregular splashes of deep, rich browns, “chestnut,”” chocolate,” and “liver brown,” overlying large splashes of various shades of “vinaceous gray.” The measurements of 54 eggs average 33.1 by 23.8 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 33.5 by 24.4, 34.3 by 24.6 and 30 by 22 millimeters.

Young: Incubation is shared by both sexes, but we have no data as to its duration. Mr. Dixon (1917) found the male bird covering the eggs more often than the female, and others have reported finding the male caring for the young. Mr. Dixon (1917) says of the young:

The young sandpipcrs were found feeding in the shaI1~wer pools, where the water was less than 1 inch deep. At times as many as five were noted in an area 1 yard square. They congregated along the water’s edge, picking up, as the tide slowly receded, many bits of food. The nature of this provender I could not make out, although the young birds would often come within 20 feet of me when I remained motionless for a few minutes. The old birds were much more shy, often taking flight or retreating to distant gravel bars upon my approach. Considerable time was spent by both young and old in making short flights about the harbor. These flights alternated with periods of food getting, and were seemingly in preparation for the fall migration. It was only a few days then until the bulk of the species left on their southward journey.

Plumages: The downy young Baird sandpiper is well colored to escape detection on the brown tundra moss. The crown and upper parts are varie’sated with black and “tawny” in an irregular pattern and dotted with white terminal tufts; the crown is centrally “tawny,” with a median black stripe, and is bordered with black; the forehead, back to eyes, sides of the head and all under parts are pure white; there is a black spot in the center of the forehead, a black stripe from the bill, through the eye, to the occiput and another below it and parallel to it; there is a white superciliary stripe and some white mottling on the back of the head and neck.

The juvenal plumage is equally concealing. The crown is sepia with buffy edgings; the back and scapulars are dark sepia with broad white edgings; the wing is like the adult except that the coverts and tertials are edged with “pinkish buff” and tipped with white; the under I)arts are like the adult but the breast is more pinkish buff and more faintly streaked. A partial postjuvenal molt, including most of the body plumage and some of the scapulars, wing coverts, and tertials and takes pla~:e inOctober or later. I have seen birds in full juvenal plumage as late as October 3; young birds migrate in this plumage. At the first prenuptial molt the following spring young birds become indistinguishable from adults.

Adults have a partial prenuptial molt in April and May, including only part of the body plumage. The postnuptial molt begins in July, when the body plumage is molted before the birds migrate; the wings are molted after the birds reach their winter home, front December to February, not long before they started to migrate north again. I have seen birds in full nuptial plumage as early as May 1 and as late as July 29, and in full winter plumage as late as April 5. The adult nuptial and winter plumages are somewhat different; the colors are brighter and richer in the spring and the markings are more distinct; in the fall the upper l)arts are nearly uniformly buffy brownish with dusky shaft streaks; the chest and sides of the breast are dull brownish buff and not distinctly streaked.

Food: Preble and MeAtee (1923) found in the stomachs of three Baird sandpipers. taken on the Pribilof Islands, amphipods, algae, ground beetles, and a weevil. Mr. MeAtee (1911) includes this species among those that eat mosquito larvae, crane-fly larvae, grasshoppers, and the clover-root curculio, all injurious insects. It feeds on the open mud flats with other species of sandpipers, but seems to prefer to feed about the edges of the shallow inland pools or where the muddy flats are partially overgrown with grass. William Brew-. ster (1925) watched some of them feeding, of which he says:

On first noticing me draw near they stood erect, with ui,stretched necks. regarding me intently and distrustfully, but their feeding operations were resumed soon after I ceased to advance. ny successive runs, S or 10 feet in length and often executed very swiftly, they moved about quickly in various directions over soft mud or through shallow water, frequently stooping to pick up small morsels of food, but not once using their bills for prohing under ground or water.

Yoce: Dr. Charles XV. Townsend (1905) says that the note, which he heard several times, seemed to him “exactly like that of the semipalmated sandpiper, a rather shrill, trilling whistle.” Mr. Brewster (1925) says that: 54267: 27: 14 the kreep call they utter in flight is sufficiently unlike that of any other wader of similar size and general coloring to he of service as a means of field identification when the birds are seen on wing. It is appreciably different from the call of any other sandpiper known to me, although not so very unlike that of the sanderling.

Field marks: The Baird sandpiper is one of the most difficult of all this group to recognize in the field, because it has no prominent distinguishing field marks peculiar to itself. It has characters in common with any one of several small sandpipers. In color and general appearance it is most like the least sandpiper; it is decidedly larger, but size is of little value unless the two are side by side for comparison; it is lighter colored above, more extensively huffy on the breast, and has darker legs. It is a size larger than the semipalmated and western sandpipers, more huffy on the breast than either, and has a shorter bill in proportion to its size than the latter. It is about the size of the white-rumped sandpiper, but is less distinctly streaked on the crown and back; the buff breast of the Baird will distinguish it when standing or even in flight; and the white rump of fuscicollis is a sure flight mark when visible. From the red-backed sandpiper, about the same Size, it can be distinguished by its shorter and straighter bill and by marked color differences. It might be mistaken for a female pectoral, but the latter is more conspicuously striped above, more like a snipe in this respect, the crown is darker, more contrasted, and the breast is darker, more abruptly separated from the white belly, and more sharply streaked with dusky; when flying the pectoral shows more white in the wings. The Baird is but slightly smaller than the buff-breasted sandpiper and very much like it; but Prof. William Rowan (MSS.) has pointed out some differences. The patterns of the backs are very similar, but the buff breasted has a much paler crown and lacks the white throat and eye stripe, as well as the clear-cut white sides and black center of the rump of the Baird. The buff breasted has yellow legs and the Baird has black. The Baird shows no white in the wings in flight. Young Bairds in juvenal plumage are easily recognized by the scaled appearance of the mantle produced by dark feathers with broad white edges.

Fall: Baird sandpipers leave their northern breeding grounds rather early. Mr. Murdoch (1885) reported the last one seen at Point Barrow on August 12, and Mr. Dixon (1917) saw none after August 15 in northern Alaska. E. A. Preble (1908) saw several flocks on migration at Great Slave Lake as early as July 10.

The main flight seems to be directly south through the Mackenzie Valley and between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River to Mexico and South America, where it probably migrates down the west coast to its winter home. But the route is also extended both east and west in the fall. Some birds fly southeastward, through the Great Lakes, to the coast of New England, whence they apparently migrate over the ocean to South America. Others migrate southward through the extreme western States.

Mr. Brewster (1925) says that they “visit Lake Umbagog (Maine) early in September, appearing oftenest during the first week in the month.” My Massachusetts dates run from August 7 to September 15. E. W. Hadeler records it in his Ohio notes from September 2 to October 11; and Edward S. Thomas has seen it there as early as August 12. It is an abundant migrant in Manitoba; we collected adults there on July 29; and C. G. Harrold tells me that birds passing through in August and September are practically all juveniles. Professor Rowan refers to it as probably the most plentiful wader in Alberta in the first half of September; he has taken it there as late as November 8. J. A. Munro calls it a regular fall migrant at Okanagan Landing, British Columbia; his earliest and latest dates are July 16 and September 18. J. H. Bowles (1918) observed it on the Tacoma Flats, Washington, from July 26 to Septeniber 5, and says:

They were found In singles, pairs, or trios, most often associating with the semipalmated plover (Aegiolitia semipolmata) when any were to be found. When flying with a company of the other small sandpipers they would separate as soon as the flock alighted to feed, the Baird’s going to comparatively dry ground for their food while the others waded about in the water and at the water’s edge. They could not have been called common, but from one to three or four were to be found on almost any day.

John T. Nichols has observed Baird sandpipers on the Pacific Ocean and writes to me as follows:

August 6, 1926, 520 19′ N., 1370 42′ W., three to six birds of this species came about a ship bound southeast for Seattle, flying with and parallel to her course. One, apparently misjudging her speed, was killed by striking the rigging forward. Perhaps the Baird sandpiper Is comparatively scarce on the Pacific coast due to an offshore migration route.

Winter: According to Prof. ~Vells IV. Cooke (1912) this sandpiper reaches its winter home in September. Chile seems to be its principal winter home, where it has been taken repeatedly in the high mountains at 10,000 to 12,000 feet and once at over 13,000.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Northeastern Asia and North and South America; accidental in England.

Breeding range: Northto the northeastern coast of Siberia (probably Koliutschin Island and Cape Serdze Kamen) ; northern Alaska (Wainwright, Point Barrow, Camden Bay, Barter Island, and Demarcation Point) ; Yukon (Herschel Island) ; Mackenzie (Franklin Bay, Baillie Island, and Cambridge Bay); and southern Baflin Island. East to Baffin Island and probably Greenland (Etah). South to Mackenzie (Cambridge Bay, Bernard Harbor, Fort Anderson, and Peel River); and Alaska (Cape Prince of Wales and Point Dall). West to Alaska (Cape Prince of Wales and Point Dali); and northeastern Siberia (probably Koliutschin Island).

Winter range: North to Chile (Tarapaca); and Argentina (Tucuman, Cordoba, and Buenos Aires). East to Argentina (Buenos Aires). South to Argentina (Buenos Aires); and Chile (Talcahuano). West to Chile (Talcahuano, Huasco, and Tarapaca).

Spring migration: In spring the Baird sandpiper is practically unknown on the Atlantic coast, the route being up the Mississippi Valley, the plains States, and (to a lesser degree) the Pacific coast. Early dates of arrival are: Missouri, Monteer, March 20, and near Boonville, April 16; Ohio, Painesville, April 25, Oberlin, April 28, and Cleveland, May 8; Michigan, Vicksburg, April 15; Iowa, Sioux City, April 9, Mason City, April 19, and Marshailtown, April 25; Minnesota, Waseca, May 10, and Hutchinson, May 18; Texas, Boerne, March 16, and Electra, April 9; Kansas, Emporia, March 27; Nebraska, Gibbon, March 19, Lincoln, March 23, and Callaway, April 7; South Dakota, Forestburg, April 6, and Brown County, April 18; North Dakota, Jamestown, May 1, and Charison, May 4; Saskatchewan, Indian Head, May 9, and Orestwynd, May 10; Mackenzie, Fort Resolution, May 19, Fort Simpson, May 20, and Fort Providence, May 26; Arizona, Fort Verde. May 5; Colorado, Loveland, March 29; Wyoming, Cheyenne, April 8, and Laramie, April 23; Montana, Knowlton, May 12, and Bitterroot Valley, May 18; Alberta, Flagstaff, April 16, Alliance, April 24, and Fort Chipewyan, May 24; California, Santa Barbara, April 27; Washington, Dayton, April 11; British Columbia, Chilliwack, April 29, and Okanagan Landing, April 30; and Alaska, Admiralty Island, May 12, Kowak River, May 20, Demarcation Point, May 23, Nulato, May 27, Cape Prince of Wales, May 28, and Point Barrow, May 29.

Late dates of spring departure are: Mexico, city of Mexico, May 19; Guerrero, Iguala, June 1; Ohio, Youngstown, June 2; Michigan, Detroit, May 24; Iowa, Sioux City, June 6; Texas, San Angelo, May 15, and Ingram, May 26; Kansas, Wichita, May 20; Nebraska, Neugh, May 26, and Valentine, May 30; South Dakota, Vermilion, May 24, and Sioux Falls, June 11; North Dakota, Charlson. May 22, and Jamestown, June 4; Saskatchewan, Indian Head, June 2, and Quill Lake, June 16; Wyoming, Yellowstone Park, June 3; Alberta, Fort Chipewyan, June 1; and British Columbia, Okanagan Landing, May 10, Vaseaux Lake, May 18. and Sumas. May 19.

Fall migration: Early dates of fall arrival are: British Columbia, Okanagan Landing, July 7; Washington, Wrights Peak, July 21, Blame, August 4, and Tacoma, August 6; California, Santa Barbara, July 25; Lower California, San Jose del Cabo, September 3; Alberta, Stratlimore, July 31; IVyoming, Toltec, July 27; Colorado, Denver, July 21, Boulder County, July 27, and El Paso County, July 29; Saskatchewan, Maple Creek, July 17; Manitoba, Oak Lake, July 12, and Red Deer River, July 23; South Dakota, Forestburg, July25; Nebraska, Callaway, August 4, and Lincoln, August 9; Texas, San Angelo, July 20; Ontario, Toronto, July 28; Michigan, Charity Island, July 9; Ohio, Bay Point, July 3; Illinois, Chicago, July 2; Massachusetts, Monomoy Island, July 14; New York, Montauk, August 14, Locust Grove, August 18, Onondaga Lake, August 27; Pennsylvania, Beaver, August 21, Erie, August 22; Mexico, Zacatecas, August 16, Colonia Garcia, September 4, and Janos River, September 5; and Patagonia, Arroyo Seco, Rio Negro, September 6, and Huanuluan, September 12.

Late dates of fall departures are: Alaska, Point Barrow, September 4; British Columbia, Comox, September 15, and Okanagan Landing, Octoher 18; Washington, Tacoma, September 27; Oregon, Netarts Bay, September 12; California, Monterey, October 24; Colorado, Boulder County, September 25, and Barr, October 5; Saskatchewan, Indian Head, September 21; Manitoba, Oak Lake, September 5, and Shoal Lake, September 14; North Dakota, Charison, September 21; Nebraska, Valentine, October 10, and Lincoln, November 3; Kansas, Lawrence, October 26; Texas, Tom Green and Concho Counties, October 20; Iowa, Burlington, October 2, and Keokuk, October 14; Ontario, St. Thomas, October 3, Toronto, October 10, and Plover Mills, October 20; Ohio, Painesville, October 11, and New Bremen, October 28; Illinois, Chicago, October 2; Missouri, Independence, October 13; Maine, Warren Island, September 20, and Bangor, November 1; Massachusetts, Cambridge, October 30; Connecticut, West Haven, October 28, and Stratford, November 3; New York, Shinnecock Bay, October 31, and Canandaigua, November 20; and Pennsylvania, Erie, October 6.

Casual records: The Baird sandpiper has several times been taken or observed in various parts of Mexico so that it seems reasonable to believe that at least a part of the birds migrate over that country. In other Central American countries and in the West Indies it is rare. Among the records are: Costa Rica (Cerro de Ia Candelaria, October 1900, Volcano Irazu, June 8, 1894, La Estrella de Cartago, November 5, 1907, and San Jose, September 18) ; and Cuba (Cocos Island). It also has been detected on the Galapagos Islands (Barrington Island, October 6, 1897) ; Lesser Antilles (Dominica, October 1, 1904); Virginia (Four-mile Run, September 3 and 25, 1894); New Jersey (Stone Harbor, September 5, 1898) ; Quebec (Montreal, September 17, 1892) ; New Brunswick (St. Andrews, September 10, 1901); and England (Rye Harbor, Sussex, November 11, 1900).

Egg dates: Alaska: 27 records, June 9 to August 24; 14. records, June 19 to July 2. Arctic Canada: 20 records, June 10 to July 21; 10 records, June 19 tp 26.