Despite its being a shorebird, the Upland Sandpiper prefers the upland grasslands that its name implies. Known for its display flights and whistling calls on the breeding grounds, Upland Sandpipers undergo long, nocturnal migrations each year, with fall migration taking place exceptionally early compared to most North American breeding birds.

Relatively social birds, Upland Sandpipers do not maintain particularly well defended breeding territories, and often migrate in small groups of up to two dozen birds. While some birds have been known to return to the same breeding area in subsequent years, it appears that they often do not.

On this page

Description of the Upland Sandpiper

BREEDING MALE

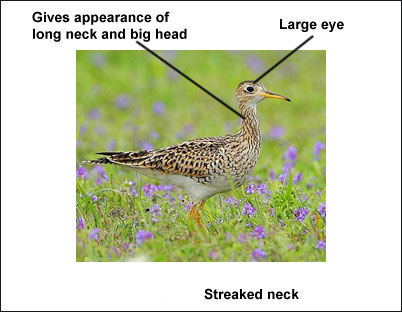

The Upland Sandpiper is a shorebird with an upright posture, a long, thin neck, and small head, and large, dark eyes. It has yellow legs and mottled brownish upperparts. Length: 12 in. Wingspan: 26 in.

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Little seasonal change in appearance.

Juvenile

Juveniles are buffier.

Habitat

Prairies and other open, grassy areas.

Diet

Insects and seeds.

Behavior

Forages by walking.

Range

Breeds in Alaska, western Canada, and parts of the northern U.S., and winters in South America.

Fun Facts

Early returning migrants form communal feeding areas, but soon break up to form pairs.

Upland Sandpipers often land on fence posts or signs.

Vocalizations

A wolf-whistle-like call is made during courtship flights on the breeding grounds.

Similar Species

Buff-breasted Sandpipers are smaller and have shorter bills.

Nesting

The nest is a grass-lined scrape placed on the ground.

Number: 4.

Color: Buff with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at 22-27 days.

– Young fledge (leave the nest) shortly after hatching but remain with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Upland Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Upland Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

BARTRAMIA LONOICAUDA (Bechstejn)

Let us be thankful that this gentle and lovely bird is no longer called Bartramian sandpiper. It is a sandpiper truly enough, but one that has adopted the haunts and many of the habits of the plovers. To those who love the rolling or hilly pasture lands of the east oi~ the broad flat prairies of the middle west, it will always be known as the upland or “field plover ~ or “prairie dove,” or, more affectionately, as “quailie.” It is a characteristic bird of the prai ries and wide open grassy fields, where it once abounded in enormous numbers. Excessive shooting for the market, where it was much in demand, reduced its numbers to an alarmingly low ebb. Dr. Thomas S. Roberts (1919) says that, in Minnesota,

Fifty years ago It was present all through the summer, everywhere In open country, in countless thousands. Now it is nearing extinction. Here and there an occasional breeding pair may yet be found, but they are lonely occupants of the places where their ancestors dwelt in vast numbers.

And with the disappearing prairies have gone these and other interesting birds that made the wide open places so attractive. When I visited the Quill Lake region in Saskatchewan in 1917, I found that practically all the prairies had been burned over or cultivated; the long-billed curlew had entirely disappeared, though recently abundant there, and I saw only one pair of chestnut-collared longspurs; but some of the upland plover were adapting themselves to the new conditions and were nesting in cultivated fields, much as the spotted sandpipers and the killdeer have learned to nest in grain fields and truck gardens. Perhaps such adaptation may be the salvation of a useful and attractive species. Some observers report it as already increasing in numbers.

Spring: W. H. Hudson (1922) describes the beginning of the spring migration from the pampas of South America, as follows.:

The north migration as a nile begins about the 15th of February and continues to the 15th of March, and It is at the beginning of the former month that the disquiet becomes noticeable. Now on one occasion the season of unrest began much earlier, in the montb of January, increased from day to day and week to week in the most extraordinary way, and continued to about the middle of March before the birds began to fly north, the migration continuing through March. On any day in February when out riding I would see from time to time a bird spring up with Its wild alarm cry and flight, and after going a little distance drop down again. Then in a minute or two another, farther away, would start up with its cry; and sitting still and watching and listening, I could see the birds rise up here and there all over the plain: rise with a cry, then settle down again; and if one tode a 100 miles to any side he would find it the. same everywhere. The birds were in a continual state of agitation, of fear; and though this state began so much sooner than usual, the actual migration did not begin till a month later than the usual time.

Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926), writing from the same general region, says:

At Tucuman, Tucuman, five were heard early in the evening of April 1 as they passed over the city traveling due north during a slow rain accompanied by heavy mist On the night of April 5 under similar conditions an extensive flight of shore birds began at a quarter of 10 and continued until half past 11. During this period 3. L. Peters, with whom I was traveling at the time, and I Identified the call of the upland plover from 38 individuals. The birds were In company with yellowlegs, solitary sandpipers, and a few golden plover. How many passed unheard in the darkness there was no way to know. The calling of these birds when in northward migration was a phenomenon of common knowledge In Tucuman during that season In the year, but all commented upon the fact that the birds seemed to have decreased greatly in abundance in recent years.

The ear]iest birds reach Texas and Louisiana early in March. Illustrating the abundance of this species in Texas 40 years ago, G. B. Benners (1887) says:

At the former place we found Immense flocks on the prairie, and they were so tame that the flock would part In the middle and let us drive between them. We often shot enough birds while going through a flock In this way to last for several meals. When they thought we did not see them they would stand perfectly still, and being the same color as their surroundings they easily escaped detection.

From there the main migration route seems to be directly northward between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

Fred J. Pierce writes to me:

On my rambles over the rolling country of Buchanan County, Iowa, in the early spring, I usually hear the Bartramian sandpiper and see the small speck high in the sky that I know is his form. A damp, cloudy morning seems to be the preferred time for the bird’s sky circling, but it may be found frequently In the early morning, too. Cloudy days are the days which it enjoys most, it appears.

Edward S. Thomas tells me that he has seen it in Ohio as early as March 26, but that the average date of arrival is April 2. It is not recorded east of Cuba in the spring, but some birds migrate across from Yucatan to Cuba and Florida and then up the Atlantic coast. When this species bred more commonly in New England it used to arrive in April, but now it is very rare here.

Courtship: The courtship flight song of the upland plover is well described in some notes sent to me by Fred J. Pierce, as follows:

The bird’s song is very Interesting, but it is given little attention in hooks relating to ornithology. On still wings, these large birds circle slowly about, usually so high as to be mere specks in the sky, and give their shrill, penetrating whistle, which will carry nearly a mile, depending upon the wind and the altitude of the whistler. First there are a few notes sounding ilke water gurgling from a large bottle, then comes the loud wkip-whee-ee-you, long drawn out and weirdly thrilling. When I first heard this strange cry I at once thought of some species of hawk as being the author of it, and I have known others to think the same thing. It Is too loud and penetrating a cry to be attributed to one of the sandpipers. I have heard the bird whistling In this manner as late as July, but I do not believe that this is a common practice. On more than one occasion I have seen the bird, after circling at such height as to be almost out of sight, close its wings and shoot to earth like a falling stone. This thrilling performance is similar to that of the prairie horned lark, which takes a headfirst drop to earth when it has finished singing its contribution to the usual spring morning chorus.

Another pretty version of the courtship is given by Katharine U. Hunter (1916) thus:

It was the springtime (1916). The prolonged wail, vague and sad, of the plovers rose In our upland pasture. I watched them carry on their odd courtship; hopping toward each other, twittering, flying away, then repeating It all again, the hopping, twittering, and retreating. UngaInly, spirit-voiced birds! Once from out the black, vibrant night came the eerie, long-drawn whistle of a plover lover.

Nesting: My first upland plover’s nest was found on May 25, 1900, near the western end of Marthas Vineyard, Mass. The birds were still fairly common here in those days and there were at least three pairs of them breeding in this and adjoining pastures. The nest was on a knoll in a sheep pasture where the grass had been cropped short except for scattered tufts, where it grew from 7 to 10 inches high, offering the necessary concealment. In one of these tufts, about a foot in diameter, a hollow had been scratched, 4 or 5 inches in diameter and nearly 3 inches deep; it was lined with small bits of dried grass and held four handsome eggs. Since then I have found several nests in Saska.tchewan. These nests were all similarly located on the dry, grassy prairies, slight hollow.s in the ground, about 4 inches in diameter and 2 inches deep, generally well hidden in rather long, thick grass; they were lined with pieces of dry grass, and the growing grass was artfully arched over them for protection. The birds usually sat very closely; once we drove over a nest, flushing the bird under the wagon; and several times we were able to part the grass over the nest or even touch the bird before she left. She usually ran or fluttered away for a few feet and then ran about near us, with her long neck stretched up above the grass, watching us and uttering her quip-ip-ip-ip notes of prote~t.

Nests found by others have been similarly described, but Prof. W. B. Barrows (1912) says that: in Michigan, it frequently nests in wet grounds, although. the nest itself Is usually placed on one of the drier spots. We have seen the birds nesting In two instances in good snipe hogs where the mud was ankle deep and dry spots few and far between.

Prof. William Rowan (1926) says that in Alberta: the nests found were very variahie in make-up and situation. One had no lining whatever and consisted of a mere scrape in the gronnd. This was in a hollow right in the open on a huge sandy area with but sparse vegetation, on which long-billed curlews (Numonius ~zmerieainu.s) were nesting. Others were in clumps of rough brush, and this is probably typical f~r this locailty. Another was in long grass. The most elaborate lining noted consisted of leaves, bents, and small twigs. One clutch of five was found and one of three, the latter no doubt incomplete, as the bird was not about and the eggs were fresh.

Edward R. Ford has the following observation on the selection of a nesting site:

As in the case of the larger ground-nesting birds, whose nests have little architectural pretension, the upland plover often deposits the first egg before any nest-building operations have been begun. It is probable that the physiological condition of the female urges her to seek a location generally favorable to the successful rearing of a brood; but the exact site of the nest may be In some measure accidental. it Is not often that one may be fortunate enough to come upon the kind of evidence best calculated to prove a theory of animal behavior, but it happened once that we found a single egg of the upland plover, unhetrayed by the presence of the parent and bidden deep in the grass. It might have been an egg prematurely laid and, therefore, not likely to receive further parental attention. If it had been a incado~v lark’s egg, for example, that would have been the Conclusion and the facts of experience would have borne it out. But here was the chance to test a theory and so, while not surprised, we were gratified, three days later, to flush a bird from the spot marked as the location of the single egg and to find there the full complement of four. About these the dry grass had taken hemispherical form and, with the addition of loose material and by reason of the impression made by the eggs themselves, as well as by the hotly of the parent, there now existed a well-defined if simple nest.

Eggs: The upland plover lays four eggs, rarely five, and perhaps sometimes only three. These are ovate to short ovate in shape, less pointed than most shore birds’ eggs; and they have only a slight gloss. In the commonest types the ground colors vary from “light pinkish cinnamon” to “pale pinkish buff”; in others they vary from “ca~rtridge huff” or “pale olive buff” to greenish white. They are more or less evenly spotted with small spots of various shades of dark browns or reddish browns, and usually with small underlying spots, rarely large blotches, of “ecru drab” or “pale drab gray.” The measurements of 66 eggs in the United States National Museum average 45 by 32.5 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 51 by 33, 48 by 35, 41.5 by 32.5, and 48 by 29.5 millimeters.

Young: The incubation period is said to be 17 days, but this needs confirmation. Both sexes share in the duties of incubation and care of the young. Katharine U. Hunter (1916) says:

The birds relieved each other at the nest: a true division of domestic cares: one bird would alight at a long distance, fold his wings, utter no cry, and, with head held low, walk through the grass, squatting lower and lower till finally he disappeared on the nest; then the female would retreat with the same caution, not spreading her wings till far from the eggs.

Doctor Coues (1874) describes the behavior of young birds and their parents very well, as follows:

Young birds are abroad late in June: curious little creatures, timid and weak, led about by their anxious parents, solicitous for their welfare, and ready to engage In the most unequal contests in their behalf. When half grown, but still in the down, the little creatures have a curious clumsy, top-heavy look; their legs look disproportionately large, like those of a young colt or calf; and they may be caught with little difficulty, as they do not run very well. I once happened upon a brood, perhaps two weeks old, rambling with their mother over the prairie. She sounded the alarm, to scatter her brood, but not before I had secured one of theni in my hand. I never saw a braver defense attempted than was made by this strong-hearted though powerless bird, who, after exhausting her artifices to draw me in pursuit of herself, by tumbling about as if desperately wounded, amid lying panting ~vith outstretched wings on the grass, gave up hope of saving her young in this way, and then almost attacked me, dashing close up and retreating again to renew her useless onslaught. She was evidently incited to unusual counige by the sight of her little one struggling in my hand. At this downy stage the young birds are white below, finely mottled with black, white, and rich hro~vn above ; the feet and under mandible are light colored; the upper mandible is blackish.

Although these tattlers are generally dispersed over the prairies during the summer, yet they affect particular spots by preference. Away from the river valleys, such spots are the numerous depressions of rolling prairie, often of great extent, which are moist or even watery at some seasons, and where the vegetation is most luxuriant. Here they gather almost into colonies. Riding into some such spot in July, when the young birds are being led about by their parents, some old bird more watchful than the rest, or nearest to the person approaching, gives the alarm with a loud outcry, the young scatter and hide. and all the old birds are soon on wing; hovering in the air, often at a great beight, crossing each other’s path, and ceaselessly vociferating their displeasure. I have often seen a dozen or twenty overhead at once, all from a little spot only a few acres in extent. Later in the season, when all the summer’s broods are on wing, they make up into flecks, often of great extent, and old and young together assume the ordinary routine of their lives. They leave these northeni regions early. I saw none after the forepart of September.

Plumages: In tim downy young upland plover, the crown, back, and rump are prettily variegated, marbled, or mottled, with black, “wood brown,” “pinkish buff,” and white, with no definite pattern. The sides of the bead and the entire under parts are pale buff or buffy white, whitest on the belly and throat. A narrow, median frontal stripe and a few spots on the sides of the head are black.

The juvenal plumage is much like that of the summer adult, but it lS much more buffy, especially about the bead and neck, which are “cinnamon-buff” or “light ochraceous buff”; the crown is nearly solid brownish black, or with only a narrow, median, huffy line; the back and scapulars are brownish black with broad “cinnamon” edgings and with little or no definite barring on the scapulars; the lesser wing coverts are sepia with “cinnamon-buff” edgings, broader than in the adult; and the median coverts are sepia, broadly tipped, and notched with “cinnamon-buff” and with a subterminal spot or bar of dark sepia. This plumage is partially molted in August and September, producing the first winter plumage, which is like the adult, except that the juvenal flight feathers and most of the wing coverts are retained. At the first prenuptial molt young birds apparently become indistinguishable from adults.

Adults have a complete postnuptial molt, beginning with the body plumage in August and ending with the wings in December and January. Their prenuptial molt in spring involves nearly everything but the wings. The winter plumage is less huffy than the spring, more grayish above and whiter below, with paler edgings, but the color pattern is about the same.

Food: The feeding habits of the upland plover are almost wholly beneficial. It is one of our most useful birds; living, as it does, in grass lands and cultivated fields, it destroys vast numbers of grasshoppers, locusts, and other injurious insects. W. L. McAtee (1912) writes:

From its habits the upland plover would naturally be expected to have a closer relation to agriculture than most sandpipers, and such proves to be the case. Almost half Its food Is made up of grasshoppers, crickets, and weevils, all of which exact heavy toll from cultivated crops. Among the weevils eaten are the cottonboll weevil; greater and lesser clover-leaf weevils; clover-root weevils; Epicaerus irnbricwtus, which is knoiva to attack almost all garden and orchard crops; cowpea curculios; Tea piaccas confertus, an enemy of sugar beets; Theccstcrnus humeraus~ which has been known to injure grapevines; and bill bugs. Thecesternus alone composes 3.65 per cent of the seasonal food of the 163 stomachs examined, and bill bugs constitute 5.83 per cent. No fewer thaa 8 species of bill bugs were identified from the stomachs. These weevils injure, often seriously, such crops as corn, wheat, harley, and rye, as well as forage plants of many kinds. The upland plover further makes itself useful to the farmer by devouring leaf beetles, including the grapevine colaspis, southern corn leaf-beetle, and other injurious species; wireworms and their adult forms, the click beetles; white grubs and their parents, the May beetles; cutworms, army worms; cotton worms; cotton cutworms; sawfly larvae; and leatherJackets or cranefly larvae. They befriend cattlTe by eating horseflies and their larvae, and cattle ticks. They eat a variety of other animal forms, such as moths, ants, and other Hymanoptera, flies, bugs, centipedes and millipeds, spIders, snails, and earth~vorms. Practically 97 per cent of the food consists of animal matter, chiefly of injurious and neutral forms. The vegetable food comprises the seeds of such weed pests as buttonweed, foxtail grass, and sand spurs, and hence Is also to the credit of the bird.

J. M. Bates (1907) says that, in Nebraska, “after the wheat is cut, and during migration, it frequents the wheat stubble and gorges itself with the waste grain.” He has also seen it in the rye stubble in Connecticut. But this does no harm, of course.

Behavior: When traveling the upland plover’s flight is swift and strong, well sustained on its long, pointed wings; and when migrating, by day or by night, it flies at a great height. In the autumn it is wary and difficult to approach, as it jumps up at long range and flies rapidly away for a long disthnce. But in the spring its flight is quite different, more leisurely; it seems to drift along so high up in the sky as to be almost invisible; it might pass unnoticed, were it not for its flute like notes. Edwin Sandys (1904) has described this very well, as follows:

This drifting flight Is characteristic of the present species, and it usually ends In a diving slant earthward, which is performed without any preceptible motion of the wings. A few feet from the ground the long, beautiful, easy descent is gently checked, and the bird alights as quietly as though it bad stooped only a yard or so instead of hundreds or thousands of feet. For a few seconds after alighting the bird is apt to keep its wings considerably elevated above its back, and the brief pose in this position is particularly attractive. Then the airy fans are sedately furled. This pretty trick of keeping the wings spread as If for a momentary study of how they should be correctly folded is not peculiar to this species. Others of its near and remote kin go through the same dainty evolution, although, perhaps, without the air of studied eare which is characteristic of Bartram’s sandpiper.

On its breeding grounds its flight is different again; it often flies along slowly and evenly, at a low elevation, 15 or 20 feet above the ground, on quickly vibrating wings, pouring out its liquid, rolling trills or flute like notes, a delightful performance; or when flushed from its nest it flies off close to the ground with short, rapid strokes of its down-curved wings, as if using only its wing tips, suggesting the flight of the spotted sandpiper. On a windy day it may occassionally be seen to soar or hover on quivering wings like a small falcon.

On the ground its movements are ploverlike, running swiftly and stopping suddenly. lit runs gracefully through the grads with its long neck stretched up to watch the pursuer; or, crouching down, it runs rapidly away and disappears in the grass. It alights frequently on fences, telegraph poles, stumps, or rocks to watch the intruder and scold at him. It is seldom seen near water, and I doubt if anyone has ever seen it swimming. It is a gentle bird at all times and lives harmoniously with its neighbors on its breeding grounds, but it does not seem to associate with other species elsewhere.

Yoice: The voice of the upland plover is one of its greatest charms; once heard in its perfection it will never be forgotten; and it often serves to identify the species when the bird can not be seen. W. H. Hudson (1922) has referred to it very attractively, as follows:

Lying awake in bed, I would listen by the hour to that sound coming to me from the sky, mellowed and made beautiful by distance and the profound silence of the moonlit world, until it acquired a fascination for me above all sounds on earth, so that it lived ever after in me; and the Image of it is as vivid in my mind at this moment as that of any bird call or cry, or any other striking sound heard yesterday or but an hour ago. It was the sense of mystery it conveyed which so attracted and impressed me: the mystery of that delicate, frail, beautiful being, traveling in the sky, alone, day and night, crying aloud at Intervals as if moved by some powerful emotion, heating the air with its wings, its beak pointing like the needle of the compass to the north, flying, speeding on its 7,000-mile flight to its nesting home in another hemisphere.

The most beautiful and striking note heard on its breeding pounds is a sweet, mellow, rolling trill, uttered as the bird flies along at a low elevation or while perched on a fence post or even on the pound; it is evidently a love note. Prof. Lynds Jones (1903) has described it very well, as follows:

The rolling cry is not unlike the rolling call of a tree toad, but of a different quality and caliber, which makes it unmistakable. The whistle is partly double, the first part pa~ing upward nearly half an octave, terminating abruptly there, the second part beginning where the first began and rapidly swelling through nearly or quite an octave, then gradually falling again and decreasing in volume to the close, several tones above the beginning. The first part of the whistle is usually rattling or trilled, and sometimes the trill is carried to the end, but oftener it becomes a clear whistle before the culmination and continues clear to the end. Tre-e-e-ee-e-e-e-e, We e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-p; or tr-r-r-r-o.o-e-e-e-e-e-p. Often the whistled part is never reached, but the call stopa as if interrupted by some threatened danger.

The alarm note, as the bird flies away from its nest or as it runs about scolding at the intruder, is an emphatic and rapidly uttered quipip-ip-ip. It also has a rich, musical note, which sounds like qua-a-ily, from which one of its local names is taken. This and a modified form of its rolling trill are often heard on migration, a prolonged, mournful, mellow whistle, drifting down out of the sky, more like the whistling of the wind than a bird’s voice.

Field marks: The upland plover should be easily recognized by its size and shape; its slender, graceful form, its delicate head and neck, and its long tail are characteristic. In flight its long, pointed wings, its dark rump, and its barred, whitish, outer tail feathers are good field marks. Its manner of flight and its notes are distinctive. FalL: About the middle of July, or even earlier, old and young birds begin to gather into flocks, move off their breeding grounds, and start on their fall migrations. The migratory flights are made mainly during the night or early evening. At this season the birds are much wilder, the leisurely behavior of spring and summer has gone, their flight is much swifter and stronger, and it is difficult to approach the loose, detached flocks which stop to feed during the day on the hoards of grasshoppers and locusts which are then to be found in the upland pastures and dry meadows., During wet spells they do not stop, but in hot, dry weather they linger to feast on the abundant insect life and become very fat. We used to expect them in Massachusetts about the last of July, but they were most abundant in August and early September. The general movement is southward, through the interior and the Atlantic Coast States and through the West Indies to South America. The earliest birds reach Louisiana and Texas early in July and arrive in Peru and Argentina in September. The last birds leave their breeding range before the end of September.

Game: The upland plover is, or was, a fine game bird. Over 40 years ago, in my younger shooting days, these birds were still fairly common in Massachusetts, but it was no easy job to make a fair day’s bag; it meant tramping many miles over rolling, or hilly pasture lands, where the wary birds rose at long range and flew swiftly away for a long distance. One had to shoot quickly and accurately to kill his bird, and perhaps chase one for several miles before getting even a long shot at him. It was a real sporting proposition with the chances much in the bird’s favor. The birds would not come to decoys, nor to the gunner’s whistle and a dog was utterly useless except to retrieve birds. A thorough knowledge of the ground and of the birds’ fly-ways sometimes brought results, when we could hide behind some fence or stone wall and wait for the birds to fly over. Even meager results were well worth while, for we had plenty of good exercise and the birds made delicious morsels for the table.

A more common and more successful, though less sportsmanlike, method of shooting them is thus described by Edwin Sandys (1904)

A popular method in many parts of the West is to drive to the birds in a buckboard, or other convenient rig. For a man who can shoot well in the sitting posture this is an excellent plant, as the birds almost invariably will permit a wheeled conveyance to approach within comparatively easy range. A clever driver Is a valuable assistance. Such a man never heads his team directly at the birds, but drives as though he merely intended to pass them by. A good Judge of distance In the open can in this way edge within comfortable range of plover which, if the driver steered straight for them, or with the gun attempted to dismount and stalk, would at once make off. I have varied the shooting from the seat by walking at the horse’s shoulders. The plover do not appear to notice the extra pair of legs. This sometimes gives the prettiest kind of shooting. All one has to do Is to Judge when sufficiently close, then stand still with ihe gun at the ready, while the team moves steadily ahead. Usually the plover xvill take wing the moment the foot-man is uncovered; but should they not, the man can gain a few yards by briskly walking toward them. I have occasionally stalked them by keeping close to the shoulder of a steady old horse that was Indifferent in the matters of smoke and loud reports.

Edward H. Forbush (1912) writes:

About 1880, when the supply of passenger pigeons began to fail, and the marketmen, looking about for some other game for thc table of the epicure in spring and summer, called for plover, the destruction of the upland plover began in earnest. The price increased. In the spring migration the birds wore met by a horde of market gunners, shot, packed in barrels and shipped to the cities. There are tales of special refrigerator cars sent out to the prairie regions, and parties of gunners regularly employed to follow the birds and ship plover and curlews by the carload to the Chicago market. These may not be based on facts, but we know that the birds came to market in great quantities.

Winter: The upland plover spends our winter months on the pampas of Argentina and Patagonia, where unfortunately it is more sought for by market hunters than it is here. Mr. Hudson (1920) writes:

This species differs from its fellow-migrants of the same family from the north to Argentina in its wide and even distribution over all that portion of the pampas where the native coarse grasses which once covered the country have disappeared, an area comprising net less than 50,000 square miles. It begins to arrive as early as September, coming singly or In small parties of three or four; and, extraordinary as the fact may seem when we consider the long distance the bird travels, and the monotonous nature of the level country it uses as a “feeding area,” It is probable that every bird returns to the same spot year after year; for in no other way could such a diAribution be maintained, and the birds appear every summer evenly sprinkled over so immense a surface.

Doctor Wetmore (1926) says:

Formerly abundant, the upland plover is now rare In the region where It spends the period of northern winter. Its winter range on the open pampa is a region so vast that it Is difficult to form a proper estimate of the actual number of Individuals of the species that remain. Among epicures the species has Inherited In part the name and reputation of the Eskimo curlew and is sought constantly by gunners to supply that demand. The few that survive frequent remote regions on some of the large estancias where they are secure until they leave their seclusion and begin their return flight northward. The majority of those that I noted were identified by their liquid calls, heard, as is the case in Washington, as they passed at night.

He says again (1927):

In the season of 1019: 20 the upland plover was reported to have Increased somewhat in abundance at Rosas in the Province of Buenos Aires, a circumstance due perhaps to protection in the United Stales and Canada. It can hardly be expected to regain anywhere near its former abundance, however, with increasing encroachment on its winter and summer ranges. Unfortunately, in Argentina it has replaced the Eskimo curlew as a table delicacy, and is so eagerly sought by gunners that its preservation in settled regions is doubtful. Those that remain must seek the pastures of remote estancias in order to survive. DISThIBUTION

Range: North and South America; accidental in Europe.

Breeding range: The breeding range of the upland plover extends north to Alaska (Kobuk River and Gens de Large Mountains); southern Mackenzie (probably Fort Smith) ; Saskatchewan (Prince Albert, Quill Lake, and Crescent Lake) ; Manitoba (Shoal Lake and Winnipeg) ; Minnesota (Clarissa, St. Cloud, Minneapolis, and Lake City) ; Wisconsin (Kingston and Kelley Brook) ; Michigan (Lovells and Zion City) ; Ontario (probably Plover Mills, Dunnville, and Kingston) ; northern New York (Canton and Potsdarn) ; southern Quebec (Hatley) ; and Maine (Farniington, Plymouth, Orono, and Calais). East to Maine (Calais) ; Massachusetts (Salem, Marthas Vineyard, and Nantucket) ; probably Connecticut (South Windsor) New York (Montauk Point) ; New Jersey (Princeton, Lawrenceville, and probably Tuckerton); Virginia (Wallops Island); and rarely South Carolina (Oakland). South to rarely South Carolina (Oakland); southern Indiana (Bicknell); Illinois (Olney and Odin); Missouri (Appleton and probably Stotesbury); Oklahoma (Copan and Fort Reno); probably Texas (Gainesville); Colorado (Barr and Denver) ; Utah (Kamas Prairies); and Oregon (Fort Kiamath). West to Oregon (Fort Klamath); northern Idaho (Lapwai and Fort Sherman); British Columbia (Newgate and Osoyoos Lake); probably Alberta (Edmonton and Athabaska Landing); and Alaska (Mount McKinley and Kobuk River).

Winter Range: The main winter range of the species is confined to the southern part of South America, north to northern Argentina (Tucuman); and southern Brazil (Irisanga and probably Mattodentro). East to southern Brazil (probably ~’Iattodentro); Uruguay (Concepcion, Sta. Elena, and Colonia); and eastern Argentina (Buenos Aires and Rio Negro). South to Argentina (Rio Negro). West to Argentina (Rio Negro, Mendoza, and Tucuman). A specimen was taken at San Angelo, Tex., January 1, 1883, but this must be considered as an acciden(al occurrence as the species at this season is usually found only in southern South America.

Spring migration: Early dates of spring arrival are: Ecuador, Chaupicuz, March 30; Chiapas, Comitan, March 29; Florida, Indian Key, March 17, St. Marks, March 23, Deer Park, March 24, and Leon County, March 25; Alabama, Barachias, March 7, Coosada, March 22, and Sand Mountain, March 29; Georgia, Macon, March 18, and Savannah, March 23; South Carolina, Mount Pleasant, March 11, and Frogmore, March 24; North Carolina, Raleigh, March 28; Virginia, Alexandria, March 22; Dist.rict of Columbia, Washington, March 21; Pennsylvania, Marietta, March 27, Plymouth, April 10, and Erie, April 11; New Jersey, Haddonfidd, April 7, and Cape May, April 12; New York, Long Island, April 1, Watertown, April 6, and Amagansett, April 11; Connecticut, Jewett City, April 16, and Saybrook, April 22; Rhode Island, Newport, April 29; Massachusetts, Woods Hole, April 10, Salem, April 12, and Cape Cod, April 12; Vermont, Woodstock, April 17, Bennington, April 22, and Rutland, April 26; Maine, Pittsfield, April 14, Plymouth, April 25, and Portland, April 30; Louisiana, New Orleans, March 9, Hester, March 16. and Lobdell, March 19; Mississippi, Biloxi, March 10, and Rodney, March 27; Tennessee, Nashville, March 31; Kentucky, Guthrie, March 20; Missouri, St. Louis, March 17, Appleton City, March 19, and Kahoka, March 20; Illinois, Rockford, March 19, Lebanon, March 20, and Canton, March 27; Indiana, Bicknell, March 13, Vigo County, March 19, and Vincennes, April 1; Ohio, Oberlin, March 20, Berlin Center, March 23, and Columbus, March 29; Michigan, Ann Arbor, March 15, Plymouth, April 8, and Livonia, April 12; Ontario, Forest, April 16, London, April 17 and Preston, April 18; Iowa, Storm Lake, March 25 Wall Lake, March 30, and Hilisboro, March 31; Wisconsin, Dela Van, March 24, Milford, April 10, and Stoughton, April 11; Minnesota, Lanesboro, April 8, North Star, April 9, and St. Cloud, April 16; Texas, Bonham, March 5, Mont Belvieu, March 8, Dallas, March 10, and Corpus Christi, March 13; Oklahoma, Copan, March 31; Kansas, Girard, March 16, Richmond, March 28, Topeka, April 1, and Onaga, April 7; Nebraska, Falls City, April 6, Badger, April 7 and Syracuse, April 9; South Dakota, Vermilion, April 9, Grand View, April 14, and Rapid City, April 15; North Dakota, Argusville, April 26, Larimore, April 26, and Marstonmoor, April 30; Manitoba, Aweme, April 26, Reaburn, April 30, Winnipeg, May 2, and Two RiVers, May 3; Saskatchewan, South qu’Appelle, April 16, Wiseton, April 25, and Indian Head, May 2; Colorado, Denver, April 18, and Colorado Springs, April 28; Wyoming, Lake Como, May 5; Montana, Billings, April 23, Columbia Falls, April 27, and Terry, May 10; Alberta, Flagstaff, May 2, Alliance, May 7, and Red Deer, May 11; and British Columbia, Osoyoos Lake, May 25.

Late dates of spring departure are: Argentina, Buenos Aires, April 3, Tucuman, April 5, and Baradero, April 13; Bolivia, Piedra Blanca, April 23; Brazil, Tonantino, May 7; Guatemala, Duenas, April 12; Mexico, Chiapas, Teopisca, May 7; Yucatan, Cancun Island, April 19; Vera Cruz, Lake Catemaco, May 5; Florida, Garden Key, May 2, Loggerhead Key, May 7, and Pensacola, May 9; Georgia, Savannah, April 28; Louisiana, Lobdell, May 15, and New Orleans, May 19; Mississippi, Biloxi, May 16; and Texas, Brownsville, April 15, Boftham, May 12, and Huntsville, May 18.

Fall Migration: Early dates of fall arrival are: New Mexico, Glenrio, July 25; Texas, San Angelo, July 4, and Lipscomb, July 10; Louisiana, New Orleans, July 5, and Abbeville, July 25; Alabama, Montgomery, July 28, and Barachias, August 22; Florida, Pensacola, August 9, and Arcadia, August 22; the Bahama Islands, Mariguana, August 5; the Lesser Antilles, Barbados, August 12, and Granada, August 24; Mexico, Jalisco, Chapata, August 27; Costa Rica, September 5; Panama, Gatun, September 1; Colombia, Cienaga, September 12; Ecuador, Carapungo, August 10, and Cerro Campania, September 24; Brazil, Matto Grosso, September 26; Paraguay, Puerto Pinasco, September 29, and Concepcion, October 3.

Late dates of fall departure are: Alberta, Red Deer River, September 22; Montana, Big Sandy, September 6; Wyoming, Little Medicine, August 15; Colorado, Fort Lyon, September 2; New Mexico, Glenrio, September 11; Manitoba, Treesbank, September 7, Margaret, September 18, and Aweme, September 28; North Dakota, Marstonmoor, September 15, and Westhope, September 24; South Dakota, Huron, September 2, Sioux Falls, September 6, and Forestburg, September 30; Nebraska, Dewitt, September 21, Badger, September 28, and Valentine, October 5; Kansas, near Wichita, Octobeir 3, Topeka, October 13, and Onaga, October 15; Texas, Grapevine, September 25, Gainesville, September 28, and Corpus Christi, October 2; Minnesota, Lanesboro, August 22, and St. Vincent, August 31; Iowa, Emmetsburg, October 14, Newton, October 22, and Grinnell, November 2; Michigan, Livonia, September 18, and Detroit, October 20; Ohio, Lakeside, October 13, Scio, October 17, and Waverly, October 23; Illinois, La Grange, October 5, Belvidere, October 24, and Rantoul, November 29; Missouri, Monteer, September 17, and Jasper City, September 27; Kentucky, Lexington, October 11; Louisiana, New Orleans, October 7; Maine, Pittsfield, September 22; Vermont, St. Johnsbury, September 25; Massachusetts, Harvard, September 14, Taunton, September 19, and Woods Hole, September 29; Rhode Island, Block Island, September 6; Connecticut, Hartford, September 3, and Litchfield, September 6; New York, Phelps, September 14, Montauk, September 17, Orient Point, September 23, and Floral Park, October 20; New Jersey, Absalom Light, September 15; Pennsylvania, Erie, September 22, Germantown, October 2, and Bridesburg, October 18; Virginia, Alexandria, November 5; North Carolina, Weaverville, November 10; South Carolina, Mt. Pleasant, October 28; Georgia, Savannah, September 20; Alabama, Barachias, October 26; Florida, Key West, October 3; Costa Rica, San Jose, November 15; Nicaragua, Escondido River, November 26; Panama, Culebra, October 22, and Davila, November 30 and Gatun, December 8; Guiana, Cayenne, October 27; Peru, Cosnipata, October 3; and Brazil, Allianca, November 9.

Casual records: A specimen of the upland plover taken February 8, 1923 at Deception Island, South Shetlands, must be considered accidental, as this is far south of its normal winter range (Bennett, 1926). The species has been reported as occasional in spring in Newfoundland (Macoun) and one was obtained on Sable Island in 1868 (Gilpin). There are several records for Quebec (Montreal and Godbout) from May 7 to October. Two have been taken in Bermuda (September 20, 1874, and September 18, 1875). In Porto Rico one was obtained by Stahl between 1878 and 1881 (Gundlach); F. A. Potts reports that he saw one September 10, 1921 near Central Aguirre, collected one from a flock of 15 on September 13, 1921, near Santa Isabel, and saw still another August 26, 1926 near Fortuna. On the Pacific coast south of 1~ritish Columbia, it is known from a specimen taken August 8, 1896, at Tule Lake, California, and one taken at Sulphur Springs, Arizona, August 18, 1874.

There are six records for England, Warwick, October 31, 1851, Cambridge, December 12, 1854, Bigswear, January 19, 1855, Falmouth November 13, 1865, Boulmer, November 21, 1879 and the Parret River in Somersetshire (date ?) ; one for Denmark Tim, November 3, 1920; one for Malta, November 17, 1865; one for Holland (Meyer) ; one for Germany, Ilessen (Naumann) ; and one for Italy, Liguria, October, 1859. It also was taken near Sydney, Australia, in 1865 (Gould).

Egg dates: New England and New York: 10 records, April 28 to June 13. Pennsylvania and New Jersey: 15 records, May 6 to June 11; 8 records, May 15 to 27. Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Dakotas, and Minnesota: 86 records, May 4 to July 1; 43 records, June 1 to 15. Ohio to Iowa and Kansas: 22 records, April 30 to June 17; 11 records, May 14 to 20.