Buff-breasted Sandpipers complete a very long migration each year, from wintering grounds in Argentina to the high Arctic, a journey taking about 3-4 months. The short Arctic summer allows time for Buff-breasted Sandpipers to raise only one brood.

Adult Buff-breasted Sandpipers leave the breeding grounds several weeks before the juveniles depart on their southward migration. The southern migration takes place over a much broader area than the northward migration in spring.

On this page

Description of the Buff-breasted Sandpiper

BREEDING MALE

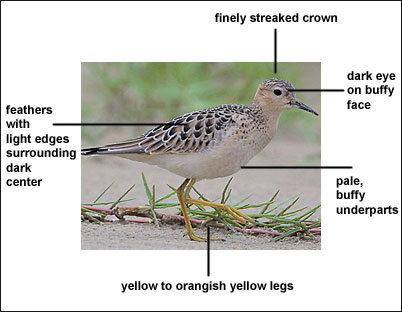

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper is a small shorebird with yellowish legs and a short, dark bill. It is slender, with an upright posture. It has a buffy face, neck, and breast, and dark upperparts feathers with pale buffy edges. Length: 8 in. Wingspan: 13 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds have buffier upperparts.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to breeding adults, but have darker upperparts.

Habitat

Buff-breasted Sandpipers inhabit pastures, prairies, and tundra.

Diet

Buff-breasted Sandpipers eat insects.

Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

Behavior

Buff-breasted Sandpipers forage by gleaning from the surface of the ground.

Range

Buff-breasted Sandpipers breed in Canada and Alaska. They winter in South America, and occur mainly across portions of the central U.S. in migration, though juveniles in particular tend to wander and can be seen, if rarely, in small numbers throughout the U.S. The population is stable.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Buff-breasted Sandpiper.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

Male Buff-breasted Sandpipers gather on leks to attract mates, performing displays involving raised wings.

Market hunting once severely diminished the Buff-breasted Sandpiper’s population, but with protection it has recovered to some extent.

Vocalizations

The flight call can be a ‘reet” or a ‘tu.”

Similar Species

Pectoral Sandpiper

The Pectoral Sandpiper has a streaked breast.

Upland Sandpiper

Upland Sandpipers are larger, with a longer yellow bill.

Nesting

The Buff-breasted Sandpiper’s nest is a depression lined with sedges, leaves, and moss, and is often placed in a clump of moss.

Number: Usually lay 4 eggs.

Color: Buffy in color with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 23-25 days, and leave the nest shortly after hatching, though associating with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Buff-breasted Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Buff-breasted Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

TRYNGITES SUBRUFICOLLIS (Vieillot)

My acquaintance with this species is limited to a few birds seen migrating in company with golden plover on the burnt-over prairies about Quill Lake, Saskatchewan. I have never seen it elsewhere. Like the upland plover, it is a sandpiper which has associated much with plover, frequents similar haunts, and has acquired some similar habits. Spring: W. H. I-Iudson (1922) gives a striking account of the spring migration of this species in Argentina during its former abundance, from which I quote, as follows:

Now, one autumn, when most of the emigrants to the Arctic breeding grounds had already gone, I witnessed a great migration of this very species: this beautiful sandpiper with the habits of a plover. The birds appeared in flocks of about one to two or three hundred, flying low and very swiftly due north, flock succeeding flock at intervals of about 10 or 12 minutes; and this migration continued for three days, or at all events three days from the first day I saw them, at a spot about 2 miles from my home. I was amazed at their numbers, and it was a puzzle to me then, and has been one ever since, that a species thinly distributed over the immense area of the Argentine pampas and Patagonia could keep to that one line of travel over that uniform green, sealike country. For outside of that line not one bird of the kind could anywhere be seen; yet they kept so strictly to it that I sat each day for hours on jay horse watching them pass, each flock first appearing as a faint buff-colored blur or cloud just above the southern horizon, rapidly approaching then passing me, about on a level with my horse’s head, to fade out of sight in a couple of minutes in the north; soon to be succeeded by another and yet other flocks In endless succession, each appearing at the same point as the one before, following the same line, as if a line invisible to all eyes except their own had been traced across the green world for their guidance. It gave one the idea that all the birds of this species, thinly distributed over tens of thousands of square miles of country, had formed the habit of assembling previous to migration at one starting point, from which they set out in successive flocks of a medium size in a disciplined order on that marvelous journey to their Arctic breeding grounds.

Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) noted migrating birds at Guamini on March 3 to 8. Prof. W. W. Cooke (1912) says that “migrants appear in the interior of Brazil and in Peru during March, but there are no spring migration data for the whole distance between Peru and Texas.” There is a heavy migration through Texas during April and then directly northward through the western part of the Mississippi Valley and the prairie Provinces of Canada to the Arctic tundra. The whole migration route in the spring seems to be very narrow. Prof. William Rowan (1927) writes:

This is a remarkable sandpiper from many viewpoints. Like .the American golden plover and the Eskimo curlew it used to exist in millions and was slaughtered in uncountable numbers. To-day there are many widely traveled collectors who have never in their lives met with it. After extensive inquiries I can discover only one spot on the continent besides our point on which migrating huff-breasted sandplpers may he relied upon to turn up in any numbers. We get it in hundreds every spring, and, roughly speaking, it frequents only one field. Odd birds or moving flocks may be noted elsewhere from time to time, but on the rough pasture that forms the main body of the point this species arrives with unfailing regularity within a day or two of the 18th of May. Like the golden plover, it seems to migrate by night, for at daybreak there may be hundreds in place of the few or none at all of the previous evening.

In his notes for 1924 he writes to me:

Two birds were seen May 19 and subsequently collected. On the 21st, five were seen shortly after sunrise with black-bellied plover, the first time that I have seen this association, but a large arrival took place during the day and there were scores in the evening. On the 24th they had reached numbers such as I have never before seen and numerous photographs were taken. On the 26th they must have been on the ground in many hundreds. The whole of their area, over a mile long, was crawling with them. There Is no doubt that this year they outnumbered every other wader we had on the place. Even so, they never formed large flocks, and I think we never saw more than 60 get up and fly together. They dropped very suddenly In numbers after this, as though they had all cleared off together, but a few were seen each day till the 30th, when a flock of 30 constituted our last record.

Pierce Brodkorb and Frank Grasett have recorded it in northeastern Illinois as early as April 27. A. G. Lawrence’s dates for Whitewater Lake, Manitoba, are from May 13 to 19. Dr. E. W. Nelson (1887) noted the first arrivals at St. Michael, Alaska, on May 31; and John Murdoch (1885) says that it arrived at Point Barrow June 6 to 8.

Courtship: Professor Rowan (1927) has given us the most elaborate account of the nuptial display of the buff-breasted sandpiper, as follows:

As we have noted It annually, there are several distinct stages to the display, but the males do not appear to be concerned In the least with the females at any time. Nor have I ever seen a female take the slightest notice of any of the displays. Nelson comments on the fact that Murdoch frequently saw solitary males displaying, yet he was observing them on the actual breeding grounds.

Probably the most frequent performance is the raising of one wing only (either one), but this has various phases. A, the wing is spread and held steadily for a few moments with the primaries horizontal and Is then closed again. B, the wing is spread with the primaries nearly perpendicular and waved round In an elipse, the bird standing still. C, the wing Is spread while the bird runs round In circles. D, the wing is held aloft while the owner runs after another bird, always, so far as I have seen, another male, which Instantly raises one wing also and starts zigzagging through the grass, the first bird giving chase. They may thus cover many yards before one suddenly collapses his wing and halts, the second immediately following suit All these single. wing performances seem to be carried out in silence.

Both wings together are used for another set of actions. E, the wings are raised similarly to a bird alighting on or arising from the ground, the body horizontal. In this attitude one bird sometimes chases another. F Is a double version of B, beth wings being raised high and waved round and round. 0, both wings are spread, undersurfaces forward, primaries horizontal, after the manner of the American eagle, the body being almost perpendicular. This may be accomplished by a rapid tick tick tick many times repeated. Two birds may do It simultaneously standing opposite to each other with the tips of the wings practically touching. H is the most characteristic of all and the most amusing to watch. Both wings are raised with the undersurfaces facing to the front as in 0, but with the primaries perpendicular, tips practically touching each other over the bird’s head. The body Is held absolutely vertical and the legs stretched to capacity (I am not sure that the birds do not stand partially on tiptoe), tail cocked out horizontally behind, while the Individual “ticks” at top speed for about a second. Each “tick” Is accompanied with a rapid jerk of the whole body. The bird then relaxes momentarily, turns through an angle of 40 to 50 degrees, repeats the performance to a fresh audience (If there Is one, for I have seen isolated birds doing this), relaxes to switch round again, and so on perhaps half a dozen times. This may also be done simultaneously by two birds, face to face, and standing so close that the wing tips appear to touch over their heads. It may then be repeated without any change of direction in the intervals. But it always seems to be done In spasms. Display is evidently Infectious, particularly in fine weather, for no sooner does one start than a dozen may be at it In a moment. But It is curious to see a bird soddenly stop In its hunt for food In order to go through one of these acts and then proceed as though it never had anything else In mind, particularly If it Is by itself. It seems so Irrational. Occasional bickering occurs, hut we have never seen serious flights or even suggestion of anything serious.

Murdoch (1885) has also observed that:

Two will occasionally meet and spar like fighting cocks for a few minutes and then rise together ilke towering birds, with legs hanging loose, for about 30 feet, then drifting off to leeward. A single bird will sometimes stretch himself up to his full height, spread his wings forward, and puff out his throat, making a sort of clucking noise, while one or two others stand by and apparently admire him.

Nesting: Roderick MacFarlane found the buff-breasted sandpiper breeding commonly on the barren grounds east of Horton River and on the Arctic coast. I find the records of some 25 nests in his notes, but the data given are very meager. One nest was “near a small river, made of a few dead leaves”; another was “a depression in the ground, lined with a few withered grasses and leaves, on the slope of a gentle eminence”; a third, he said, was ” precisely similar to that of the golden plover. The female made a short, low flight to a distance of about 12 yards, ~vlien the nest was approached within 9 or 10 feet.”

Murdoch (1885), at Point Barrow, “collected the eggs in considerable abundance”; he says that “they were never seen on the lower marshy portions of the tundra, but always confined themselves to the high and dry banks, or what we call the black tundra.” The eggs were deposited “in a shallow depression in the ground lined with a little moss,” where they harmonized very well with the black and white of the ground and moss.

Eggs: The buff-breasted sandpiper lays four eggs; one set of five is recorded. The shapes vary from ovate pyriform to pyriform, usually decidedly pointed. The prevailing ground colors are very light, from “cartridge buff” to dull white; in some darker colored eggs they are “olive-buff,” “chamois,” or “cream buff.” They are heavily and boldly marked, chiefly at the large end, where the markings are often confluent, with longitudinal and somewhat spiral blotches and with small spots and blotches scattered over the whole egg. An occasional egg is only sparingly marked with small spots. The markings are in dark browns, “bister,” “Sepia,” “liver brown” and “livid brown,” sometimes “Saccardo’s ~ or “chestnut brown.” There are usually underlying blotches and spots in various shadesof “brownish drab” or “drab-gray.” The measurements of 62 eggs in the United States National Museum average 37 by 26 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measures 40 by 27, 37.5 by 27.5, 34.5 by 25.5, and 35.5 by 25 millimeters.

Plumages: J have never seen a downy young buff-breasted sandpiper and I doubt if any one else has. Young birds are in juvenal plumage when they migrate southward. They are like the adults, except as foll~ws: The feathers of the mantle are sepia with an olive tinge, “dark grayish olive,” narrowly edged with cream white, giving a scaled appearance, whereas in the adult these feathers are brownish black or black, with very broad edgings of “cinnamon-buff” or “pinkish buff”; the feathers of the lower back, rump and upper tail coverts are from “hair brown” to “fuscous,” tipped with “cinnamon,” whereas in the adult these are brownish black, broadly edged with ” cinnamon-buff “; the inner webs of the primaries, on the under side, are much more finely and closely sprinkled with black than in the adult, which has larger, more widely scattered and hence more conspicuous black spots. This last character probably persists through the first year. The postjuvenal molt and the first prenuptial molt are accomplished in South America. I have seen no specimens illustrating these.

Adults have a complete molt, apparently late in the fall or in the winter, the wings being molted last. Doctor Wetmore (1926) shot a male on September 21 that was still in worn breeding plumage. Birds molting primaries have been taken in February and March. Summer and winter plumages are very similar and the sexes are alike, except that the female is much smaller than the male.

Food: Professor Rowan (1927) says:

I am indebted to the Biological Survey at Washington for kindly analyzing the contents of 17 stomachs, spring taken. Roughly, 40 per cent consisted of Coleoptera, adults anti larvae, and 50 per cent of Diptera, chiefly larvae and pupae. Seeds of Polygonurn, Potaniogetoa, and Eleocftaris were present to the extent of 1 per cent. The rest consisted of spider and insect remains. I shall be glad to send a detailed list to anyone who may be interested.

Behavior: The same observer writes:

The buff-breasted sandpiper, like Bartram’s, is a plover In its ways and habits rather than a sandpiper. Even in its coloration It differs radically from tho common sandpipers. It is extraordinarily tame and confiding at times. When the mood seizes it, one could without difficulty wipe out every bird of a flock, provided one killed or wounded one with the first shot. The remainder will return again and again to a wounded bird. The noise of the gun seems to have little more than momentary effect.

Owing to the muddy tone of their plumage, these birds are exceptionally difficult to see on the tyl)e of ground that they so habitually frequent. One can easily walk into a flock without knowing it till the birds get up almost under foot. This is made the easier by their habit of “freezing.” They stand immobile on being approached, not necessarily crouching, generally the very reverse, but xvlthout movement they readily enough escape observation. If they start moving as one gets nearer, it is always on the run. They then carry their necks “craned,” scatter widely, and zig-zag hither and thither rather after the manner of partridges, of which they frequently remind one.

A flock will seldom rise in unison, but the nearer birds will merely fly over and settle on the remote side of the further ones. Even when the buff-breasts are amongst sandpipers, such as Baird’s, Semi-palmateds, etc., five times out of ten they will remain on the spot if the others are scared up. A really large flock is rare. We estimated the number of buff-breasts on a few acres of grass one morning at about 2,000, and we spent several hours in trying to photograph them. They were scattered in clumps in all directions. Althougb we walked through them from one end to the other more than once, thus tending to herd them, the largest number we were able to put up together was about 150. This constitutes the largest flock we have ever seen. The typical loose association Is evi(lent in the photograph. The birds merely flew round and settled again in the vicinity.

On windy days these, like other waders, become exceedingly restless and impossible to approach. They then perform the most remarkable gyrations, always hut a few feet above the ground, and seldom rising and falling vertically, as do so many others. They attain great speed and keep In close formation, moving in absolute unison. As such a flock turns in the sunlight there can be no possible error as to identity, for the whole mass looks yellowish. A single bird, In favorable light, may also give one the Impression of being yellow.

George H. Mackay (1892a) says of their habits in Massachusetts:

Of the few which I have seen I have remarked their extreme gentleness and desire to be In company with other birds. On one occasion I had one alight among my plover decoys on the upland (which they seem very fond of frequenting), and, not wishing to shoot it, I allowed It to remain for quite a while so I could watch It. During this time It moved about with unconcern, apparently not being aware that its supposed companions were of wood. It seemed so gentle that I determined to see how near It would permit me to approach, and it was not over 5 or 6 feet from me when it flew away, but only for a short time, howArer, for it returned and alighted In the course of 10 or 15 minutes. Having no desire to shoot it, I allowed it to remain until It departed not to return. All the birds that I have seen come Immediately to the decoys on perceiving them, and alight without hesitation or fear. Their flight Is rapid, with many turns and zigzag movements, and near the ground, constantly turning up so as to show their entire under parts.

Much of the behavior of the buff-breasted sandpiper, while on the ground, reminds one of the upland plover; it seems to prefer the grassy places rather than the open flats or shores, and often runs away to hide in the grass rather than fly; in running it lifts its feet rather high, as if accustomed to walking through grass; and it often stops and stands with its neck stretched up looking at the intruder, just as the upland plover does.

Voice: It is not a noisy bird, and seems to have a limited vocabulary. Professor Rowan (1926) says:

The spring note of the buff-breast on the other hand, Is the most unusual and diagnostic wader note that I know. The only thing It reminds me of is the song of the short-billed marsh wren (Cistothorus stdllaris), which produces a very excellent Imitation of two stones being chipped together. The note of the buff-breast has the same quality about It; but, Instead of being loud and clear, It Is quiet and very short, and might be described as Uk. This species, however, Is rather silent. I call this the spring note, but perhaps It should more correctly be termed the adult note, for we have not a single good record of an adult In the autumn, wherefore I am only familiar with young at this season. Like some other waders (e. g. willet), birds of the year have a very different call or calls from spring adults. In the case of the buff-breast the note of the young is so like the pectoral’s: Harold considers It shorter and less harsh: that, although distinguishable In the field, It can hardly be described adequately by Itself.

Doctor Wetmore (1926) writes: “As they rise they may give a low call that resembles ohwup, somewhat robinlike in tone; a second call note is a low trilled pr-r-r-reet. The species is to be confused in the field with no other shore bird.”

Field marks: Professor Rowan (1927) says, on this point:

The absence of white margins and black center to the rump, and hence the lack of contrast in this region, I have found to be the most useful diagnostic character in the field. The wing patch is also valuable. The extraordinarily rounded head seen in silhouette against the sun or In bad light at reasonable range has more than once proved useful. The note is always diagnostic.

Doctor Wetmore (1926) writes:

When In the air or on the ground they are distinctly buff in color, with a glimpse of the marbled underwing surface as they rise or pass, and a flash of the gray tail with its darker markings as they alight. On the ground in profile, they show a long neck and long legs, while the short bill is suggestive of that of a pigeon. The neck is drawn in during flight.

E. A. Doolittle (1923) observed that:

The greenish legs, finely streaked crown, huffy breast and sides of head, lack of streak through eyes, and long pointed wings reaching beyond tail were all good field marks while the bird was at rest; while lack of wing bars and rounded tall were striking when the bird took flight.

Fall: The fall migration is much more widely extended than the spring; the main flight is directly southward through the center of North America, but it is so spread out that some birds appear on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Professor Cooke (1912) says: “The main body of migrants follows the Barren Grounds to the shores of Hudson Bay, thence almost due south across the Mississippi Valley to the coast of Texas, and through Central America to northwestern South America, and diagonally across the interior of South America to Argentina.” A limited flight swings eastward, south of Hudson Bay, or perhaps across it, to the eastern Provinces of Canada and New England. The species is so rare on the Atlantic coast south of Long Island as to indicate the probability of an oversea flight to the West Indies and South America. On the Pacific coast it seems to be very rare, though perhaps it has been overlooked, south of Washington, where it is probably of regular occurrence. D. E. Brown has sent me several records for Washington, the dates ranging from September 3 to 20. Major Allan Brooks (1924) says that he has noted it every year that he has been on the British Columbia coast.

In the interior the adults come along during the last three weeks in August, and the young birds all through September. In New England the dates are about the same. Here they were occasionally seen in small flocks, but now they are so rare that single birds are more often seen iii company with upland or golden plover on the rolling uplands, or with other sandpipers on the meadows.

Winter: It evidently spends the winter south of Argentina, for Doctor Wetmore (1926) saw the first one on September 21 in Paraguay and the last one on November 13 near Buenos Aires; he did not see it again until the return flight in March. Mr. Hudson (1920) says:

It begins to arrive, usuafly in small bodies, early in the month of October; and during the summer is seldom met with in flocks of any size on the pampas, but is usually seen on the dry, open ground associating in small numbers with the golden plover, the whimbrel, and other northern species. I, however, think it probable that It travels farther south than its fellow-migrants from North America, and has its principal feeding-grounds somewhere in the interior of Patagonia; also that its northern journey takes place later than that of other species.

Doctor Wetmore (1027) says:

The species frequented open flats or muddy shores near lakes or channels, where it was subject to considerable hunting, as several of those see;i had been crippled by shooting. From observations at Onamini, it appeared that the species has some resting station in northern Patagonia, perhaps near the mouths of the Rio Colorado and the Rio Negro, or some of the large alkaline lakes of that region. The small numbers remaining are preserved in some such place, but apparently the species is near extinction.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: North and South America.

Breeding range: The buff-breasted sandpiper is known to breed only on the Arctic coast of northwestern North America from Alaska (Cape Smythe, Point Barrow, and probably Cape Halkett) east to Yukon (Herschell Island) ; and Mackenzie (Fort Anderson and Bernard Harbor). It has been detected in slimmer and may breed at Nulato and Fort Egbert, Alaska, and at Winter Harbor, Franklin (ilennessey), while it also has been noted at this season in eastern Siberia (Cape Wankarem and the south coast of the Okhotsk Sea).

Winter range: The winter range appears to be restricted to southern South America. They have been noted at this season in Uruguay (Montevideo) ; and Argentina (Cordoba, Missiones, Rio Parana, Buenos Aires, and Lavalle).

Spring migration: spring migration of the buff-breasted sandpiper is imperfectly known, and only a few records are available. It has been detected at Guamini, Argentina, on March 8, at Paramba, Ecuador, on April 22, and at Gatun, Panama, on March 29. On the Atlantic coast of the United States it is practically unknown at this season, old records at Frogmore, South Carolina (May 5), and Kendali (April 20), and Howard (May 8), New York, constituting the meager data at hand.

The main flight is seemingly up the Mississippi Valley, but even in that region, the record is incomplete. The data available are: Louisiana, Bird Islands, May 18; Kentucky, Bowling Green, April 27; Missouri, April 15, and May 20; Illinois, Chicago, April 27; Ohio, Columbus, May 6, 1923 (only record); Iowa, Norway, April; Minnesota, Madison, May 16, and Wilder, May 21; Texas, Corpus Christi, March 17, and Gainesville, April 23; South Dakota, Sioux Falls, May 12, and Fort Sisseton, May 22; North Dakota, Jamestown, May 6, and Harrisburg, May 7; Mackenzie, Fort Chipewyan, May 24, and Fort Simpson, May 29; and Alaska, Demarcation Point, May 26.

Fall migration: The fall record is more complete and dates of arrival and departure can be given with greater consistency. Early dates of arrival are: British Columbia, Chilliwack, July 23; Keewatin, Cape Eskimo, August 10; Manitoba, Shoal Lake, August 9; North Dakota, Grafton, August 14; South Dakota, Harding County, August 15; Nebraska, Neligh, August 12, and Waverly, August 14; Texas, Tivoli, August 3; Gainesville, August 4, and Brownsville, August 4; Minnesota, Minneapolis, August 1; Iowa, Charles City, August 1, and Sioux City, August 2; Indiana, Millers, August 30; Ohio, Lake County, August 19; Illinois, Chicago, August 16; LQuisiana, Abbeville, August 4; Quebec, Godbout, August 7, and Henley Harbor, August 20; Maine, Scarboro, August 1, and Damariscane Island, August 26; New Hampshire, Rye Beach, August 25; Massachusetts, Ipswich, August 7, Cape Cod, August 16, and Nantucket, August 26; Rhode Island, Little Compton, July 22; New York, Canandaigua, July 24, Shelter Island, August 22, Syracuse, August 24, Rockaway, August 25, and Montauk Point, August 26; New Jersey, Toms River, September 8; Virginia, Wallops Island, September 5; North Carolina, Currituck, September 12; Florida, Lake Jackson, September 12; Costa Rica, San Jose, September 7; Colombia, Cienaga, August 12; Peru, Pebas, August 3, and Yquitos, September 2; and Paraguay, Puerto Pinasco, September 21.

Late dates of fall departure are: Washington, Westport, September 3, and Tacoma, September 20; California, Morro, September 14, 1923 (only record for the State); Montana, Yellowstone County, September 1; Colorado, l3arr, August 25 and September 4 (only records); Manitoba, Lake Winnipeg, September 5, and Oak Lake, September 9; North Dakota, Jamestown, September 30; Nebraska, Lincoln, October 25; Kansas, Salina, October 10; Texas, Brownsville, October 7, and Corpus Christi, October 10; Wisconsin, Pittston, September 7, and Rock Prairie, September 10; Michigan, Kalamazoo County, September 17; Ohio, Columbus, September 9, Indiana, Lafayette, September 10; Illinois, Chicago, September 28, and Beach, October 2; Missouri, Independence, September 15; Kentucky, Bowling Green, September 7; Quebec, Magdalen Islands, September 13, and Port Burwell, September 28; Maine, Cape Elizabeth, September 13; Massachusetts, Nantucket, September 8, Plum Island, September 15, Monomoy Island, September 19, and Cape Cod, September 24; Rhode Island, Middletown, September 10, Newport, September 15, and Compton, September 23; Connecticut, New Haven, September 30; New York, Orient Point, September 8, Rockaway, September 13, and Mastic, October 6; Lesser Antilles, Barbados, October 6; Costa Rica, San Jose, October 8; and Panama, Gatun, October 18.

Casual records: The buff-breasted sandpiper has been recorded as taken once at Cardenas, Cuba (Gundlach). There are fifteen or sixteen records for the British Isles, all being for the period from July to September, except one, taken in May, 1829, at Formby, Lancashire. It also has been recorded from Abbeville, Picardy, France (Dalgleish); and from the Province of Owari, Japan (Steineger). A record of this species from Heligoland, May 9, 1847, is considered by Seebohn as possibly T. subminuta.

Egg dates: Arctic coasts of Canada and Alaska: 37 records, June 1 to July 18; 19 records, June 28 to July 3.