The Pied-billed Grebe is a nocturnal migrant that prefers to swim or dive away from danger rather than fly. When dawn is approaching, a migrating Pied-billed Grebe suddenly lands on any body of water it can find. It moves north early in the spring, and moves south in response to forming ice.

Pied-billed Grebes usually require a running, flapping start across the water to become airborne. They can also sink slowly down under the water by releasing air from their air sacs and squeezing air out from between their body and their feathers.

The Pied-billed Grebe is a small swimming and diving bird with a compact body and a rather short, stout bill. Breeding birds have a blackish forehead and chin, a white bill with a black band, and mostly tan or brownish plumage.

Breeding birds have a blackish forehead and chin, a white bill with a black band, and mostly tan or brownish plumage.Pied-bills often look gray to black.

Description of the Pied-billed Grebe

BREEDING MALE

The Pied-billed Grebe is a small swimming and diving bird with a compact body and a rather short, stout bill. Breeding birds have a blackish forehead and chin, a white bill with a black band, and mostly tan or brownish plumage.

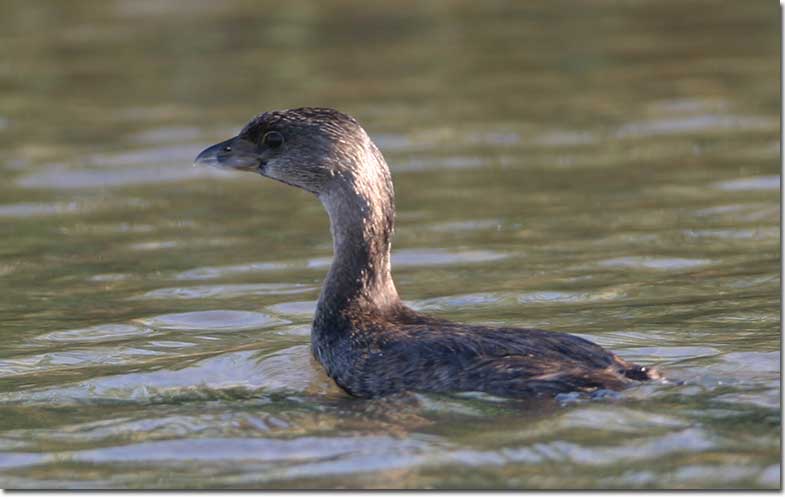

Winter plumage, © Greg Lavaty.

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds lack the black forehead and chin, and have a more uniform, brownish bill.

Juvenile

Juveniles resemble winter adults, but have a striped cheek pattern.

Habitat

Pied-billed Grebes inhabit ponds, lakes, and marshes.

Diet

Pied-billed Grebes dive to capture aquatic prey, including insects, fish, crustaceans, tadpoles, and other items.

Behavior

Pied-billed Grebes have legs set far back on their bodies, a position that is good for swimming but poor for walking on land. To take flight they must have a running start, paddling furiously through the water while flapping their wings. They are usually seen swimming on the surface, and frequently diving in search of prey. When threatened, Pied-billed Grebes sometimes slowly submerge straight down, leaving their head out of the water like a periscope.

Range

Pied-billed Grebes breed across much of the U.S. and south central Canada. They winter along the westernmost U.S. and across the southern U.S. Pied-billed Grebes have increased in recent decades.

Fun Facts

Pied-billed Grebes migrate at night, though southern populations may be resident year-round.

Pied-billed Grebes are aggressive and very territorial, even chasing other species away.

Young Pied-billed Grebes often ride on their swimming parents’ backs.

Vocalizations

The Pied-billed Grebe’s song is a series of barks. Females also make soft grunts.

Similar Species

Eared and Horned Grebes have thinner bills, significant reddish and black plumage during the breeding season, and significant white plumage during winter.

Nesting

The nest is a floating pile of plant material placed in shallow water.

Number: Usually lay 4-8 eggs.

Color: Bluish-white and often stained by nest material.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 23-27 days, and leave the nest shortly after hatching, though they continue to associate with the adults for several weeks.

Photos of Pied-billed Grebes

Winter birds lack the black forehead and chin, and have a more uniform, brownish bill. Sexes are similar. Photograph © Sam Crowe.

Note the dark mark in front of the eye. Photograph © Sam Crowe.

The tail shows a small puff of white, visible in this and the following photo. Photograph © Sam Crowe.

Photograph © Sam Crowe.

Juveniles resemble winter adults, but have a striped cheek pattern. Photograph © Sam Crowe.

Very young Pied-billed Grebes have an amazing head pattern. Photograph © Elaine Wilson.

Young Pied-billed Grebe. Photograph © Alan Wilson.