Not as numerous as some other shorebirds, and with a somewhat smaller breeding range, the Stilt Sandpiper nests in sub-arctic Alaska and Canada, but can be seen in migration across much of North America, especially in the east. The Stilt Sandpiper is a deeper water forager than most other sandpipers, and seeks invertebrates.

Male Stilt Sandpipers establish nesting territories with nests typically spaced a few hundred yards apart, though they fly up to five miles away to forage for food. If a young sandpiper survives its first year, it typically lives to be three to five years old, though the record age is nine years.

Stilt Sandpiper (Calidris himantopus) feeding in a shallow pond near Churchill, Manitoba, Canada.

On this page

Description of the Stilt Sandpiper

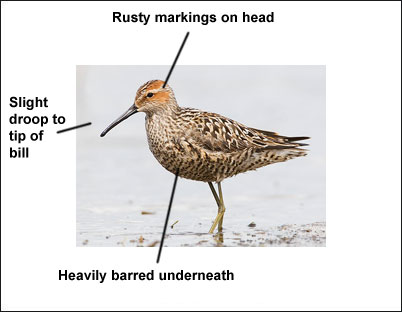

BREEDING MALE

The Stilt Sandpiper is a medium shorebird with yellowish legs and a long, somewhat down-curved bill. Breeding birds have heavily barred underparts, dark upperparts marked with white, and a strong white supercilium bordered by reddish. In flight, white wing linings are visible. Length: 8 in. Wingspan: 18 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds are plainer, with white underparts and gray upperparts.

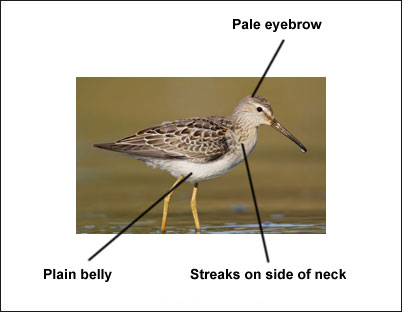

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to breeding adults, but have white feather edging producing a scaled appearance on the upperparts.

Habitat

Stilt Sandpipers inhabit mudflats, marshes, and tundra.

Diet

Stilt Sandpipers eat insects, mollusks, and seeds.

Behavior

Stilt Sandpipers forage in shallow water, probing into the water and mud.

Range

Stilt Sandpipers breed in Canada and Alaska. They winter from the southern U.S. to South America, and occur primarily across the eastern U.S. in migration. The population is stable.

Fun Facts

Stilt Sandpipers tend to feed in deeper water than other Calidris sandpipers.

Female Stilt Sandpipers often leave the young with the male a few days after they hatch.

Vocalizations

The flight song is a series of buzzy trills. A husky “qwerp” flight call is also given.

Similar Species

- Dowitchers

Dowitchers are stockier and have longer bills. - Long-billed Dowitcher

- Short-billed Dowitcher

Nesting

The Stilt Sandpiper’s nest is a depression placed on a ridge or hummock and frequently surrounded by water.

Number: Usually lay 4 eggs.

Color: Off white or olive with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at about 19-21 days.

– Young leave the nest shortly after hatching, though associating with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Stilt Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Stilt Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

MICROPALAMA HIMANTOPUS (Bonaparte)

Strangely enough I have never seen, or rather recognized, a stilt sandpiper in life. As it is often associated with the lesser yellowlegs and so easily mistaken for it, I may have overlooked it. It is a rare bird in the localities where most of my work on shorebirds has been done and it does not seem to be very common anywhere. It is more common on migrations in the Mississippi Valley than elsewhere, on its way to and from its restricted breeding range on the barren grounds and Arctic coast of Canada.

Spring: The spring migration is almost directly north from the Gulf of Mexico to Great Slave Lake and then down the Mackenzie Valley and other valleys to the Arctic coast. It is rare in spring on the Atlantic coast. R. J. Longstreet writes to me that he saw three on May 4 and 5, and four on May 8, 1925, in Volusia County, Florida. C. G. Harrold tells me that it is a common spring migrant in Manitoba, “even abundant at times, a flock of nearly 300 being seen in May, 1924, at Whitewater Lake.” A. G. Lawrence records it, at the same lake, as early as May 5 and as late as June 2; he calls it “uncommon to fairly common.” At Beaver Lake, in northern Alberta, William Rowan saw flocks of from 20 to 25 birds every day from May 20 to 28, 1924. P. IL. Hatch (1892) says that, in Minnesota, “they come in small flocks, and keep mostly about shallow ponds, and along the smaller streams flowing through the marshes,” but he has “found them on the sandy beaches of some of the larger lakes on several occasions.” He says “they are shy and exceedingly vigilant, making it no easy matter to get them.”

Nesting: Comparatively little is known about the nesting habits of the stilt sandpiper. Roderick MacFarlane (1891) found it “fairly abundant, on the shores of Franklin Bay, where a number of nests with eggs and young were discovered. It is, however, very rare in the interior, only one nest having been taken at Rendezvous Lake on the borders of the wooded country east of Fort Anderson.” A nest with three eggs, found on June 22, 1863, is described in his notes as “near a small lake and composed of a few decayed leaves placed in a depression in the ground, partly concealed by a tuft of grass;” the female was flushed off the nest and shot. The nest found at Rendezvous Lake is not described, but one found at Franklin Bay, on July 6 or 8, 1865, containing four fresh eggs, was “a mere depression in the ground, lined with a few withered leaves and grasses.”

Eggs: Four eggs is probably the usual number laid by the stilt sandpiper. They are ovate pyriform in shape. The only eggs I have been able to locate are the three sets in the United States National Museum, collected by MacFarlane. J. H. Riley has kindly sent me descriptions and measurements of these. In the set of four eggs the ground color is “ivory yellow” with large irregular blotches and spots of two shades of “mummy brown,” and a few rather large shell markings of” hair brown,” the latter mostly towards the larger end. The spots and blotches are a little heavier towards the larger end, also, but in no sense do they form a ring. Another set of two eggs is similar, but the spots and blotches are much smaller, more numerous, and more evenly distributed over the surface; some of the “mummy brown” spots are even becoming scrawls. The third set of two eggs are like the set of four, except that the ground color is “pale olive buff” and the “mummy brown” blotches are on the average smaller. The measurements of these 7 eggs average 35.5 by 25.1 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes 36 by 25, 35 by 26, 35 by 25 and 36 by 24.5 millimeters.

Young: Mr. IvicFarlane (1891) says: “On one occasion we could not. help admiring the courage and ingenuity displayed by both parents in defense of their young, which resulted in saving two of the latter from capture.”

Plumages: In natal down the stilt sandpiper closely resembles several of the other species of tundra-nesting sandpipers. It can generally be recognized by its relatively longer legs and by its longer bill, with a broader tip. The head markings are also a little different. The forehead, cheeks, and throat are dirty white, with a broad, black, median stripe from bill to crown, another (loral) from bill to eye, and a short one (malar) below it. The crown, back, wings, thighs, and rump are variegated or marbled with black (predominating) and dull browns, “tawny” to “ochraceous tawny,” and profusely dotted with dull white terminal down tufts; these dots form a distinct circle around the crown patch, below which the whitish sides of the head are marked with “ochraceous tawny.” The lower throat is washed with pale buff, and the rest of the under parts are white.

In the juvenal plumage in August the head and neck are streaked with gray and whitish; the crown is dusky, with huffy edgings; the mantle is brownish black and dusky, with “tawny” edgings on the blackest feathers in the back and scapulars, and with pale buff or whitish edgings on the rest of the mantle and tertials; the under parts are white, suffused with pale buff on the throat, breast, and flanks; the wing coverts are edged with pale buff or whitish; the upper tail coverts are white and but little marked; the central tail feathers are dusky, edged with white, and the others are white, marc4ned with dusky. This plumage is not worn long, for the postjuvenal molt of the body plumage begins late in August and lasts through September. producing a first-winter plumage. Th,is is similar to the winter plumage of adults, but can be recognized by the juvenal wing coverts, some scapulars, and tertials.

I have been unable to trace the first prenuptial molt of young birds, which is probably accomplished in South America, nor have I been able to recognize a first nuptial plumage. Possibly young birds may not come north during their first spring.

Adults have a partial prenuptial molt in April and May, involving the body plumage, most of the scapulars, and some of the wing coverts and tertials. The complete postnuptial molt begins sometimes during the first week in July and sometimes not until the last of that month, and is completed in about two months, including the wings. A specimen taken in Argentina on September 21 had renewed the wings and practically all of the body plumage. In winter plumage the upper parts are brownish gray, with narrow, light edgings; the sides of the head and the under parts are white, with little or no barring; there is a dark streak through the eye, but no rusty on the head.

Food: Audubon (1840) watched a flock of about 30 stilt sandpipers feeding, of which he writes:

I saw a flock of about 30 long-legged saadpipers alight within 10 steps of me, near the water. They Immediately scattered, following the margin of the retiring and advancing waves, in search of food, which I could see them procure by probing the wet sand in the manner of curlews, that Is, to the full length of their bill, holding It for a short time in the sand, as if engaging In sucking up what they found. In this way they continued feeding on an extended line of shore of about 30 yards, and it was pleasing to see the alacrity with which they simultaneously advanced and retreated, according to the motions of the water. In about three-quarters of an hour, during all which time I had watched them with attention, they removed a few yards beyond the highest wash of the waves, huddled close together, and began to plume and cleanse themselves. In the stomachs of several individuals I found small worms, minute shellfish, and vegetable substances, among which were the hard seeds of plants unknown to me.

N. B. Moore watched a stilt sandpiper feeding in Florida and says in his notes:

It alighted within 20 feet of me and commenced feeding at once, in water that nearly covered the tarsi. I was surprised to see it slowly step along, carrying its bill immersed nearly up to the base, and sweeping it slowly from side to side, much In the manner of the roseate spoonbills, which were at the same moment feeding near by. I noticed no action like that of swallowing at any time, its motions being continuous: as described: until I shot it to make sure of the species.

Stuart T. Danforth (1925) says of the food of this species in Ports Rico:

Seven stomachs (five collected on August 20 and two on September 17) were available for examination. Animal matter composed 70.1 per cent of the food, and vegetable matter of 29.9 per cent. Bloodworms (Chironomid larvae) were the largest food item, formIng 72.8 per cent of the animal food. From isO to 600 bloodworins were found in all hut two of the stomachs. Dytiscid larvae formed 15.~ per cent, small Planorbis snails 7.1 per cent, and mosquito larvae 0.8 per cent of the animal matter. The vegetable matter was composed of seeds. Seeds of Persica~-ia formed 80 per cent of the vegetable matter; seeds of Ses ban em era, 7 per cent; seeds of Composltae 10.2 per cent, and rubbish 2.8 per cent.

Prof. William Rowan writes to me:

In very dirty weather, particularly if a gale is blowing, stilt sandpipers have been noted hunting for food high and dry on rough pasture. This is probably an exceptional performance correlated with this type of weather, for it has never been observed at other times.

John T. Nichols says in his notes:

Just how this species makes use of its somewhat peculiar bill is not very clear. I have seen it alighted on flooded dead marsh, wading in the puddles and picking at the projecting dead stubble about on Its own level. Again I find in my Journal reference to three birds which alighted in water to their thighs, and immediately began to feed, moving about close together, immersing the bill to the eyes for an instant or two.

Verdi Burtch (1925), referring to a bird he saw at Branchport, N. Y., says:

I saw it catch and with much effort swallow a small frog, after which it lost all interest in fishing. It walked off a few steps and stood on one foot, all humped up and with eyes closed; quite a contrast to the usual alert sandpiper pose.

Behavior: Audubon (1840) writes:

The flight of these sandpipers is rapid and regular. They move compactly, and often when about to alight, or after being disturbed, incline their bodies to either side, showing alternately the upper and lower parts. On foot they move more like curlews than tringas, they being as it were more sedate in their deportment. At times, on the approach of a person, they squat on the ground, very much in the manner of the Esquimaux curlew, Numenius borealis; and their flesh is as delicate as that of the species just named.

Dr. Arthur A. Allen (1913), after referring to the companionship and resemblance between stilt sandpipers and lesser yellowlegs, says:

In theIr habits, however, the two species were quite different The yellowlegs were always rangy birds and covered a great deal of ground while feeding. Even when resting they were conspicuous by the nervous jerking of the head and neck. In flight they usually formed fairly compact flocks but scattered upon alighting. The stilt sandpipers, on the other hand, were quiet birds and went about their search for food very systematically, gleaning everything in theIr way. They frequently fed in a space a few yards square for over an hour at a time. When at rest they showed none of the nervous traits of the yellowlegs, being much more sedate, neither jerking the head nor tilting the tall. In flight they were quite similar to the yellowlegs, but as soon as they alighted they bunched and frequently the whole flock fed with their bodies nearly touching. Like the yellowlegs, the stilt sandpipers were seldom seen upon the exposed mud but preferred wading where the water was from 1 to S inches in depth, so that the entire head and neck frequently disappeared beneath the surface of the water while feeding. The notes of the two birds, though similar in form, were wholly unlike in quality, that of the stilt sandpiper being mellower and lower in pitch.

Coues (1878) at first mistook birds of this species for dowitchers and did not recognize them until he had them in his hands. He says:

They gathered In the same compact groups, waded about In the same sedate, preoccupied manner, fed with the same motion of the head, probing obliquely In shallow water with the head submerged, were equally oblivious of my approach, and when wounded swam with equal facility. The close structural resemblances of the two species are evidently reflected in their general economy.

Mr. Nichols says in his notes:

On alighting the stilt sandpiper sometimes lifts its wings halfway for an instant, a mannerism characteristic of the tattler group, which it would seem to have acquired from its associate, the yellowlegs.

Voice: Following are Mr. Nichols’s notes on this subject:

The common flight note of the stilt sandpiper is very like the single whistled irAn of the lesser yellowlegs, but recognizably lower pitched and hoarser, at times with a quaver, whr-r-u, and varying down to a shorter, less loud wArn p. An unlond, reedy ahcr has been heard from two birds when flushing.

Though with different feeding habits, stilt sandpiper, dowitcher, and lesser yallowlegs frequent the same grounds, asseciate very freely on the wing, and all three have a very similar flight note, though sufficiently different for identification. Perhaps the very lack of close relationship in these birds has facilitated convergence of their habits and calls, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that close association, even imitation, has played some part in bringing about the likeness of thetr voices. The greater yellowlegs differs more from the lesser, both in flight note and flight habits, than do these other two unrelated species.

Field inarks: I quote again from Mr. Nichols’s notes on field characters, as follows:

On the wing the stilt sandpiper resembles the lesser yellowlegs closely. Its smaller size Is scarcely appreciable, even In a flock of yellowlegs, the members of which will usually be at slightly varying distances from the observer. Adults have appreciably darker (barred) lower parts, and young birds, particularly, are grayer above than yellowlegs at the same season in this latitude. The somewhat shorter legs do not project so far beyond the tail, but the proportionately longer bill (with slight apparent drop at its tip) Is the stilt sandpiper’s best field mark. Its bill is proportionately longer even than that of the greater yellowlegs, with which this species is unlikely to be confused, varying as It does away from the lesser yellowlegs in an opposite direction, both as regards size and in other subtle characters. The head and neck of a yellowlegs are more ‘shapely,” differing in this respect somewhat as a black duck differs from sea ducks.

On the ground the stilt sandpiper stands lower than a yellou’legs, having decidedly shorter legs, and correspondingly higher than our other shore birds of the same size. The color of its legs, dull olive green, is usually diagnostic. The legs are sometimes yellowish, and very rarely yellow, only one such having come under the writer’s personal notice, a young bird in southward migration. The name “greenleg” Is often used for It by Long Island baymen, who also suspect It of being a cross between yallowlegs and duwitcher. At sufficiently close range the marginatlon of the feathers of the upper parts Is quite unlike the spotting of the yellowlegs’ plumage.

The broad white stripe over the eye is conspicuous in any plumage and the whitish tail shows in flight, as different from the whitish triangle on the rump and back of the dowitcher or the white rump of the yellowlegs. Most of these field marks, however, are too subtle for easy recognition, unless seen under favorable circumstances.

Prof. William Rowan has sent me the following notes:

Identification marks of the stilt are excellent and It Is quite an easy bird to spot in almost any circumstances. It has a rump pattern all to itself and is therefore readily detected in flight. The end of the tail is darker than that of a yellowlegs, but the white of the rump end, instead of forming a straight line across the back, Is horseshoe shaped. Although the turnstone and semipalmated plovers are reminiscent, they are quite distinct and not to be confused. When wading: the birds prefer to be belly deep: the carriage of the head makes the species unmistakable. The bill is always held and thrust beneath the surface perpendicularly. This necessitates a straight neck. In profile the feeding Individual can be mistaken for no other sandpiper, is quite distinct from the yallowlegs, and can really only be confused with a phalarope. The Wilson phalarope habitually wades in this part of the world, swimming only occasionally, but Its markings are distinctive. A flock of stilts is the most characteristic sight and the species can be identified at a great distance. The curious position of the head Just referred to and the crowding of the individuals into each other make a quite unmistakable combinatIon. They feed practically shoulder to shoulder, seldom scattering. The yellowlegs of a flock are always scattered, and the general aspect of the indivIduals is entirely different. Stilts never bob their heads after the manner of yellowlegs.

Fall: The fall migration of adults begins very early, coming along with the dowitchers and first summer yellowlegs. I have an adult female in my collection, taken on July 5, 1885, on Monomoy Island, Massachusetts. The main flight of adults comes along during the latter half of July and first half of August, in this State, and the young birds come through in August and September; but this is a rare bird here, and the flight generally lasts for only a few da.ys.

Mr. Nichols tells me that:

On Long Island the stilt sandpiper Is usually uncommon, occurring in small numbers often closely associated with lesser yellowlegs or dowitcher. Rarely it occurs in great waves or flights as on August 12, 1912. This flight was made up exclusively of adult hirds, so far as the writer’s observations went. For the remainder of that season the species was unusually common. If, in ordinary years, some 200 stilt sandpipers are present on Long Island in southward migration, there were probably 3,000 in 1912. The earliest I have seen this species south on Long Island Is July 10, 1921, two or three or more individuals associated wIth 40 or 50 lesser yellowlegs.

In the interior this species is commoner than it is on the Atlantic coast. Mr. ilarrold says that in Manitoba it is fairly common in the fall, adults being noted as early as July 5; the young birds are usually with the lesser yellowlegs in the fall. Mr. Hersey collected a series for me in Manitoba between July 18 and 29, 1913. Stilt sandpipers were formerly sold in the markets, mixed with bunches of summer yellowlegs, but their sale is now prohibited, and they are too small to be considered as game birds.

Winter: The winter home of the stilt sandpiper seems to be in southern South America, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Chile, but actual records substantiated by specimens are not numerous. Ernest Gibson (1920) shot some “out of a flock of over 100,’ which “might easily have been 200, so closely were they massed.” They “were feeding on marshy ground; and as the flock rose at” his “approach, circled and passed away, the white under surfaces were quite dazzling in the sunlight.” This was near Cape San Antonio, Buenos Aires, on December 27, 1913.

Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) writes:

The stilt sandpiper was encountered only in the Chaco, west of Puerto Pinasco, Paraguay, though It has been said that It Is common In some parts of the Province of Buenos Aires in winter. At kilometer SO, on September 20, 1920, the first arrivals, a flock of a dozen, were recorded at the border of a lagoon; as I watched they rose suddenly to whirl rapidly away to the south. ward. On the following day about 20 were seen, and an adult female was taken. At Kilometer 170, on September 24, a small flock passed down the nearly dry channel of an alkaline stream known as the Riacho Salado, while at Laguna Wall (kilometer 200) about 30 were seen September 24, and 40 on the day following. The birds were found in little flocks, often mingled with other waders that walked or waded through shallow water on muddy shores where they probed with their bills for food.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: North America, south to southern South America. The stilt sandpiper is one of the rarer shore birds and but little is known of its range and migrations.

Breeding range: North to probably northeastern Alaska (Demarcation Point); probably Yukon (Herschel Island) ; Mackenzie (Fort Anderson, Rendezvous Lake, Franklin Bay, and probably Kogaryuak River); and probably Keewatin (Cape Eskimo). East to probably Keewatin (Cape Eskimo); and probably Manitoba (Fort Churchill and York Factory). South to probably Manitoba (York Factory); and Mackenzie (Artillery Lake). West to Mackenzie (Artillery Lake); and probably Alaska (Demarcation Point). Eggs have been taken only in northern Mackenzie.

Winter range: Imperfectly known, but probably north to Tepic (Acaponeta River); Zacatecas; Tamaulipas (Matamoros); rarely Texas (Corpus Christi); rarely Louisiana (State Game Preserve); and Cuba. East probably to Cuba; and Brazil (Ilha Grande). South probably to Brazil (Ilha Grande); Uruguay (Colonia); and Chile. West to Chile; Bolivia (Falls of the Madeira) ; central Peru (Chorillos and Yquitos); Ecuador (Babahoyo); Colombia (Cienaga); Nicaragua (Mom otomb o); Guatemala (Duenas); Oaxaca (Tehuantepec); Jalisco (Manzanillo and La Barca); and Tepic (Ocaponeta River).

Spring migration: Early dates of arrival in the spring are: Florida, Banana Creek, March 10, Smyrna, March 26, and Pensacola, April 5; North Carolina, Cape Hatteias, May 19; New York, Long Island, May 18; Connecticut, Westport, May 28, and West Haven, May 30; Rhode Island, Sakonnet, May 9; Maine, Saco, May 5; Missouri, Kansas City, April 30; Illinois, Chicago, May 26; Iowa, Sioux City, May 7, Emmetsburg, May 10, and Wall Lake, May 23; Wisconsin, Racine, April 10; Minnesota, Wilder, May 1, and Waseca, May 14; Texas, Bonham, March 29; Kansas, McPherson, May 7; Nebraska, Kearney, May 6, and Neligh, May 10; South Dakota, Harrison, May 5, Vermilion, May 9, and Sioux Falls, May 14; North Dakota, Harrisburg, May 1, and Sweetwater, May 5; Manitoba, ïWhitewater Lake, May 12; Colorado, Barr, April 27, Fort Lyon, May 2, Colorado Springs, May 14, and Loveland, May 20; Wyoming, Cheyenne, May 25; Alberta, Fort Chipewyan, June 6; Mackenzie, Fort Resolution, May 19, and Athabaska delta, June 4; and Alaska, Demarcation Point, May 23.

Stilt sandpipers also have been detected as late as April in Cuba and Jamaica while a late date for their departure from Lake Palomas, Mexico, is April 7, from Dummetts, Florida, April 14 and Port Orange, Florida, May 5.

Fall migration: Early dates of arrival for the species on its return from the North are: Colorado, Barr, July 5; North Dakota, Benson County, July 1, and Nelson’s Lake, July 14; South Dakota, Forestburg, July 7; Nebraska, Lincoln, July 19; Iowa, Sioux City, July 12; Texas Corpus Christi, July 3; Ontario, Toronto, July 18; Maine, Chebeague Island, July 19, and Scarboro, July 30; New Hampshire, Rye, July 31; Massachusetts, Cape Cod, July 4, and Needham, July 24; Rhode Island, Newport, July 6, and Block Island, July 15; New .York, East Hampton, July 11; North Carolina, Churches Island, July 29; Bahama Islands, fortune Island, August 5; Barbados, July; St. Batholomew, September; and Paraguay, Kilometer 80, September 20.

Late dates of fall departure are: British Columbia, Sumas Lake, September19; Colorado, Fort Lyon, September 8, Larimer County, September 9, and Barr, October 5; Mackenzie, Fort Simpson, August 19, and Lower Slave River, August 27; Manitoba, Carberry, August 29, and Qu’Appelle, September 16; Nebraska, Lincoln, November 11; Kansas, Lawrence, September 19; Wisconsin, Kelley Brook, September 13; Iowa, Burlington, September 28; Ontario, Toronto, September 26; Ohio, Columbus, October 4; Illinois, Chicago, September 1, Grand Crossing, September 23, and Cantine Lake, September 28; Missouri, St. Louis, September 12, and Kansas City, September 28; Maine, Scarboro, September 16; Massachusetts, Chatham, September 20, and Cape Cod, September 29; Rhode Island, Newport, September 9; New York, Buffalo, September 16, Bronx, September 19, Cayuga, October 10, and Jamaica, November 28; New Jersey, Morristown, October 16; Maryland, Paw tuxent River, September 8; District of Columbia, Anacostia River, October 26; North Carolina, Churches Island, September 23; and Florida, Fernandina, October 10, and Key West, November 1.

Casual records: The rarity of the stilt sandpiper makes it difficult to determine whether some occurrences should be listed as regular migrants or as accidentals. Some of the following cases may be on the regular migration route of the species: Bermuda, two early in August, 1848 and one in early September, 1875; Newfoundland, Cow Head, September, 1867; Nova Scotia, Sable Island, August 18, 1902; New Brunswick, Courtenay Bay, September 8, 1881; and Montana, Chief Mountain, August, 1874.