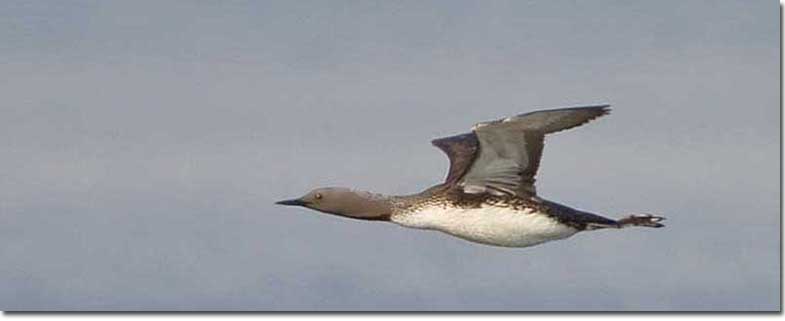

The smallest of the world’s five loon species, the Red-throated Loon is a high-arctic breeder but winters along the east and west coasts of North America. Migration usually takes place in small groups and at a low elevation above the water or land. Red-throated Loons propel themselves underwater with their feet.

One-fourth or more of Red-throated Loons may fail to breed in a given year, often due to inclement weather at their northern breeding latitudes. Once nesting, storms can cause water or ice to destroy nests. Red-throated Loons have been known to live over 23 years in the wild.

Description of the Red-throated Loon

BREEDING MALE

The Red-throated Loon is a small loon with a thin bill that is often held up at a slight angle.

Male/breeding plumage:

– Reddish throat.

– Gray head.

– Brownish upperparts.

Photograph © Glenn Bartley

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter birds have white throats and cheeks, and white markings on a dark back.

Juvenile

Juveniles resemble winter adults.

Habitat

Coastal areas and tundra lakes.

Diet

Fish.

Behavior

Forages by diving.

Range

Breeds From Alaska to Greenland and winters along the east and west coasts of North America. Also occurs in Russia and Europe.

Fun Facts

The Red-throated Loon is the smallest loon in the world, although there are only five species of loons worldwide.

Unlike other loons, Red-throated Loons are capable of taking off from land.

Vocalizations

Gooselike cackling is given in flight.

Nesting

The nest is a pile of vegetation.

Number: 2.

Color: Olive with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at 24-29 days.

– Young fledge (leave the nest) in a day after hatching but remain with the adults for some time.

The red in the throat can be difficult to see when the bird is in flight or seen at a distance. Wing beats are strong and fast. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Compare this loon in full breeding plumage with the molting loon below. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Molting adult. Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

Winter birds have white throats and cheeks, and white markings on a dark back. The back is speckled with white. Adults in non-breeding plumage have white necks. Young birds have gray on the side of the neck. Greg Lavaty.

Young Red-throated Loon. Greg Lavaty.

Long, thin lines in flight. White belly and chest. Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Loons are seldom seen on the ground. Note how far back on the body the feet are located. Photograph © Greg Lavaty.