More than most species of songbirds, the Cassin’s Sparrow’s abundance and distribution can change dramatically from one year to the next depending on weather conditions. In dry years, Cassin’s Sparrows may breed farther east, and be scarce in an area in which they were common the previous summer.

Male Cassin’s Sparrows typically sing from an exposed perch, but they also have a flight song that makes them very conspicuous early in the nesting season. At other times of the year, they can be much harder to locate.

On this page

Description of the Cassin’s Sparrow

BREEDING MALE

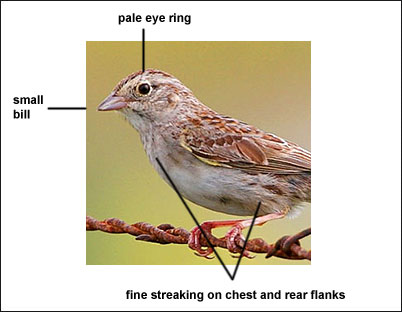

The Cassin’s Sparrow is rather nondescript, having a gray breast, pale throat, a rufous crown with fine streaking, and gray and rufous upperparts.

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

None.

Juvenile

Juveniles have streaked underparts.

Habitat

Cassin’s Sparrows inhabit brushy fields and arid grasslands.

Diet

Cassin’s Sparrows eat insects and seeds.

Behavior

Cassin’s Sparrows forage on the ground in relatively open areas.

Range

Cassin’s Sparrows breed across parts of the southwestern U.S. They winter mostly in Mexico. The population has declined in recent decades.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Cassin’s Sparrow.

Fun Facts

In wet years, Cassin’s Sparrows sometimes breed farther west, and in dry years farther east, taking advantage of just the right amount of aridity and vegetative cover.

Cassin’s Sparrows have a “skylarking” display in which they fly up giving introductory notes and then float downward giving a trill.

Vocalizations

The song consists of melancholy, trilled whistles. A high call is also given.

Similar Species

- Botteri’s Sparrows

Botteri’s Sparrows have a more noticeable supercilium and a larger bill.

Nesting

The Cassin’s Sparrow’s nest is a cup of grass, twigs, bark, and weeds and is lined with finer materials. It is placed on or near the ground, well hidden in grass or a shrub.

Number: Usually lay 3-5 eggs.

Color: White.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 11 days and fledge at about 9-10 days, though remaining dependent on the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Cassin’s Sparrow

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Cassin’s Sparrow – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

AIMOPHILA CASSINII (Woodhouse)

Contributed by FRANCES C. WILLIAMS and ANNE L. LESASSIERHABITS

Cassin’s sparrows are small, nondescript, ground-dwelling birds. Unless they are singing they are rarely seen, as their plumage blends perfectly with the dry grasses among which they spend their lives.

This species is most abundant in the short grass plains of western Texas and Oklahoma, eastern New Mexico, and Colorado. Although open, grassy areas with a few scattered shrubs are preferred habitat, in western Texas these fringillids also occur in mesquite grassland areas if the mesquites are small with open areas among them. When found near draws where trees and thick brush grow, Cassin’s sparrows remain on the open slopes, rarely going into the brushy areas at the bottom of the draw. They are almost never found in chaparral thickets.

J. Van Tyne and G. M. Sutton (1937) observe that this species shows a marked preference for open, grassy country in Brewster County, Texas, but found it occurs also in less open, more brushy sections. They state that it is abundant in the yucca-dotted grasslands north of Marathon, where the concentration of singing males gives somewhat the effect of a colony.

In New Mexico, Florence M. Bailey (1928) notes that “Although found sometimes in the tall grass and in meadowy tracts around springs, colonies of the sandy Cassin Sparrow are most numerous on dry plains with a growth of short grass interspersed with small shrubs and bushes. They are also seen on the mesquite plains in yucca patches * *

In the only record of Cassin’s sparrow occurring in a cultivated area, Margaret M. and Leonard B. Nice (1922) observed four birds in alfalfa fields about Kenton, Oklahoma,” May 30 to June 2,1922. John C. Johnson, Jr. (1956) encountered three singing males along a fence row and among abandoned oil well equipment in an area of approximately two acres in the moderately overgrazed open prairie two miles north of Norman, Okla. N. S. Goss (1891) reports that in Kansas this sparrow “frequents the barren spots and sandy lands, dotted hero and there with low, stunted bushes, bunch grass or cactus.”

Cassin’s sparrow occasionally occurs in or near mountainous areas. The southern slopes of the Davis Mountains in Trans-Pecos, Texas, are treeless, grassy plains, with a few scattered yuccas of various species. A road traverses these plains for about 15 miles. Along this road 27 singing Cassin’s sparrows were counted one July day. About a mile high in the I?avis Mountains are open meadows with oaks on the surrounding slopes; this species occurs in the open meadows. It has been found as high as 4,000 feet on the mesa that surrounds the Chisos Mountains. J. Van Tyne and G. ~vl. Sutton (1937) collected it in the foothills of the Santiago Mountains, as well as in the Glass Mountains of western Texas. The vegetation in all these areas consists of widely spaced bushes interspersed with grass. Florence M. Bailey (1928) found it “in the foothills of Mount Capitan to the lower edge of the juniper belt at about 5,500 feet * * *

“A single specimen was taken in the fall of 1883 near Willis [New Mexico] at 7,800 feet (Henshaw), where it was, of course, a straggler.”

All these descriptions of the Cassin’s sparrow’s habitat have one thing other than “open grasslands” in common; each mentions the presence of small shrubs, bushes, or yuccas. The birds use these as singing perches. The species does not usually inhabit areas that are entirely grass, unless the field is surrounded by a fence where the birds may perch. Although these fringillids are noted for their flight songs, they do not rise from the ground to sing, but rather launch themselves into the air from the highest perch available.

J. Stokley Ligon (1961) and Allan R. Phillips (1944) report that in New Mexico and Arizona these sparrows are more common in wet seasons than in dry ones. The reverse is true in the Panhandle and southern plains of western Texas.

Spring and courtship: Although a few Cassin’s sparrows remain in southern and western Texas throughout the winter, they are not conspicuous until the last two weeks of March when they begin singing. It is assumed there is a movement of migrating birds into the area at this time, though possibly the birds may be present several weeks before they begin singing. The first songs are very soft, and are usually given from an inconspicuous perch. As the season progresses, the males sing loudly from the highest perch available.

Territorial defense is carried on by song duels between males. If only one male is in the area, he usually sings from the top of a bush. As soon as another male arrives, the first male begins singing in flight and the second male replies. On one occasion, as male “A” was singing, male “B” began singing about 1,500 feet away. “A” rose into the air to the height at which he usually sang, then flew steadily in the direction of “B.” As he flew, he twice rose slightly in his flight and sang. When he was about 50 feet away from “B,” he lit on the top of the tallest bush, where he sang three times. “B” flew up twice, singing, but did not approach “A.” “A” then flew back until he was again in his own territory.

On another occasion, two males were singing only twenty feet apart. Each was singing in flight: first one, then the other, flying up. Then, as male “X” was floating down to his perch, male “Y” flew rapidly toward him, calling tree, tree, tree, tree. When “Y” was about five feet away, “X” retreated to a more distant perch and “Y” turned abruptly back to his own perch. Behavior like that of “A” and “B” is more common, while active defense of territory such as that shown by “Y” is rare. To date no actual physical contact between two males has been observed.

Several authors have commented on “colonies” of Cassin’s sparrows, including Mrs. Bailey (1928) and J. Van Tyne and G. M. Sutton (1937). It is true that this species concentrates in favorable areas. But on the south plains of western Texas, cassinii is plentiful everywhere in uncultivated areas and gives no impression of colonialism.

The extent of territory one male defends varies considerably. In a census of a 50-acre tract north of Midland, Texas, three pairs were found to have territories wholly within the tract, and four additional pairs had territory partly within the area. Another 20-acre tract contained only one pair, and both members of the pair ranged over most of the territory.

During courtship pairs of Cassin’s sparrows spend much time flying about their territories, just above the tops of the bushes. Both the male and female give rapid “tzee-tzee-tzee” calls as they chase each other around. Occasionally after a male has flown up as if to give his flight song, he instead gives the “tzee-tzee” call for as long as it takes him to float to his perch. When the pair desists briefly from the chasing routine, the male may assume a display posture. He elevates and fans his tail, holds his head down, his wings outward, then flutters his wings and tail. The female may perch low in the same bush during the display. (The male and female are distinguished oiily by identifying the male as he sings, then keeping him steadily in view as he goes about his activities.)

The following behavior of a courting I)air was somewhat unusual: A male sang steadily in one small area for 30 minutes. He sang both perched and in flight. Suddenly a second bird flew up from the ground, sat on top of a mesquite, hung its head, held its tail erect, fluttered its ‘wings rapidly, all the while uttering “tzee-tzee-tzee-tzee.” The singing bird was at the peak of his flight, and sailed downward to light about 3 feet from the displaying bird. They immediately took off together, flying about 2 feet apart, to a height at least twice as high as the singing bird had been flying. They floated down, landed in the grass some distance away, and were lost to view. Neither sang nor called during this flight.

In many hours of watching the behavior of Cassin’s sparrows, the authors observed copulation only once. The female was not displaying or calling, but was perched on top of a mesquite bush near where the male was singing. The male flew to her from a perch, not from his song flight. Probably the birds usually copulate while on the ground where they are hidden from view in the grass.

Nesting: The nest is situated on the ground at the foot of a small shrubby plant or low bush; in a bunch of grass; among grass growing in a brush heap. Or it may be in a low bush, seldom over 12 inches from the ground. Often the nest is in the midst of a tangled patch of the slender branching cactus Opuntia leptocaulis, where the nest may be either on the ground or ‘within the branches of the cactus. Descriptions in the literature of nests of this species are about equally divided between nests on the ground and nests above ground.

L. J. Hersey and R. R. Rockwell (1907) found a nest near Barr, Cob., in a Gutierrezia, or small rabbit-brush. “The nest was built among the closely interwoven stems and branches of the plant, the bottom of the nest resting on the ground but not sunken into it.” Henry Nehrling (1896) wrote of this species in Texas, “The nests which I had an opportunity to examine, were all placed on the ground, near a tuft of grass or on the side of a low spiny cactus. A typical nest found May 3, 1882, was built under the overhanging leaves of the Yucca Jilamentosa in a mesquit prairie.” George Finlay Simmons (1925) writes of the nest sites be found near Austin, Texas: “On ground among roots at foot of small, slender-stemmed rat-tail or needle cactus (Opuntia leptocaulis P.D.C.), small evergreen shrub or bush, or in bunch of grass; rarely up to one foot in low hushes.” A nest we found near Midland, Texas was in an Opuntia leptocaulis growing in the middle of a small mesquite bush. The bottom of this nest was 6 inches from the ground, and the rim was 8~ inches from the ground.

The cup-shaped nest is composed of weedstems, dead grass, and rarely, flowers. It is lined with fine grass, rootlets, grasstops, and sometimes a little horsehair. A nest near Midland, Texas was constructed entirely of grass with the thicker stems on the outside and finer grass on the inside. The outside diameter at the rim was 4 inches, the inside diameter 2~ inches. The inside depth was 2 inches.

A nest Herbert Brandt (1940) found was “Deep in the heart of [a] * * * cactus * * * a tiny, well-concealed nest that could be found only by taking apart the protecting pad. * * * It was rather bulky, and composed of grass, with a lining of finer grasses, horsehair, and some red cattle hair.”

The nest described by L. J. Hersey and R. R. Rockwell (1907) near Barr, Cob., was a neat structure when supported by the numerous stems, but when removed proved to be rather flimsy in construction and very fragile. It was composed entirely of dry grass blades and stems, weed stems and barks, and vegetable fibers, lined with fine grass blades and a very few fine grass stems. The nest was unusually deeply cupped, with the sides built perpendicularly and slightly rimmed in. It measured as follows: outside, 3~’i inches in height, 4 inches in long diameter, and 3Y2 inches in short diameter; inside, depth of nest cavity from rim of nest 2Y2 inches, short diameter 2 inches, and long diameter 2~4 inches. The circumference of the inside of the rim was slightly less than that of the cavity where the eggs lay. The rim of the nest was not symmetrical but varied in height and thickness to conform to the branches among which it was placed, and altha built near the outer edge of the bush was supported and concealed on all sides by the spreading branches of the plant, which was about 10 inches high and 18 inches in diameter.

Eggs: Cassin’s sparrow lays usually four, but sometimes three or five eggs. The eggs are nearly oval, but somewhat elongated. They are white, unspotted, slightly glossy. The measurements of 44 eggs average 19.0 by 14.6 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 20.9 by 15.4, 18.9 by 15.6, and 17.8 by 18.0 mullmeters.

Young: The incubation period for Cassin’s sparrow is unknown. The parent birds forsake their nest for the slightest cause. Many observers returning to a previously discovered nest have found it deserted and the eggs gone.

Both parents feed the nestlings. At a nest near Midland, Texas the young were fed small moths and caterpillars up to 2 inches in length. In one hour, the parents made five trips to the nest, making a “chittering” noise as they approached the nest. Whether or not this was an alarm reaction to the observer’s presence is not known.

J. C. Johnson, Jr., (1956) describes the behavior of a pair of Cassin’s sparrows at the nest: For an hour * * * both remained most of the time along an approximately 100-yard stretch of fence. The male sang from posts and wire, never during flight, with silent periods of up to 20 minutes; its mate spent much of her time on the ground near the feoce, occasionally flying for brief visits to a growth of small wild plums about 75 yards to the soutb. No young birds were in evidence, nor did either adult appear to be visiting a nest. Within half an hour after moving into my car, using it as a “blind,” I twice saw the male, with food in its beak, fly directly from one fence post to a particular small area of ground nearby; During the next half hour the female also visited this spot twice with food, though she arrived by a much more devious route. The nest held five nearly-fledged young * *

Plumages: The natal down is sparse, and very dark. The gape is a dull orange-yellow. Richard R. Graber (1955) describes the juvenal plumage as follows: “Feathers of forehead and crown blackish brown, edged with light buff (pattern irregular streaking). Nape cream, streaked with dark brown. Back feathers blackish, edged with cream (scaled pattern). Rump similar but lighter. Longest upper tail coverts black along shaft, edged with light reddish brown. Deck retrices vary from dull gray to light rusty brown (color phases?); suggestion of barring from black herringbone pattern along shaft. Other retrices largely black, narrowly light edged, and marked (ventrally) with dull white, terminally. Primaries edged with white, secondaries and tertials with cinnamon buff. Secondaries edged terminally with white, tertials margined with white. Coverts, like remiges, black. Lessers and greaters edged with cinnamon buff, medians and greaters tipped with white (two narrow wing bars). Lores and eyering whitish. Obscure superciliary line, white streaked with black. Side of head tinged with huffy, flecked with dark brown. Under parts light cream-colored; chin, throat, breast, sides, and flanks conspicuously streaked with black. Belly and crissum unmarked. Crissum more richly colored than other under parts. Leg feathers brown and cream.”

The postjuvenal molt occurs in late fall (Graber, 1953; A. R. Phillips, lYsib). The breast streakings sometimes persist through the first winter to as late as March.

Robert Ridgway (1901) gives the following description of the adult Cassin’s sparrow:

Adults (sexes clike).: Above light brown, broadly streaked with light gray, the pileum streaked also with black or dusky; scapulars and interseapulars marked with dusky subterminal spots or bars in a light brown field, the margins of the feathers light ash gray; upper tail-coverts with roundish, cordate, or transverse subterminal spots of blackish, and margined terminally with pale grayish; middle rectrices light brownish gray, with a narrow, pointed median stripe of dusky, this more or less irregular or serrated along edges, the points throwing off more or less distinct indications of darker bars across the gray on either side; edge of wing pale yellow; under parts with chest, sides, and flanks very pale brownish gray, the flanks sometimes distinctly (often broadly) streaked with brown or dusky; elsewhere beneath dull white (under tail-c overts sometimes pale bully); sides of throat sometimes marked with a dusky submalar streak.

The bill is dusky, moderate in size, but somewhat broad at the base. The wings are short and rounded, the tail long and rounded. Legs and feet are flesh-colored. The iris is brown.

Food: Food of the Cassin’s sparrow consists of insects during the nesting season and seeds the remainder of the year. Joe ‘r Marshall, Jr., writes that the stomachs of two specimens taken July 27, 195k in the Santa Rita mountains of Arizona were full of green caterpillars and shiny small beetles. In Midland, Texas, Cassin’s sparrows eat caterpillars during the spring months. In the winter they eat whatever small weed and grass seeds are available. Mio (a grain sorghum) was eaten by the species at a feeding station, and a Cassin’s sparrow was caught in a trap baited with fine “chick chow” consisting of ground corn and mio. Flower buds of the blackthorn bosh (Oortdalia spatliulata) are eaten in season.

Cassin’s sparrows seem to exist very well without drinking water. In 20 years in west Texas, where the species is abundant, the authors have seen cassirtii drink water only four times. Nesting areas of these fringihids are often some distance from water, and the birds rarely leave their territories.

Behavior: George M. Sutton and Thomas D. Burleigh (1941) comment that the Cassin’s sparrow “is an exceeding inconspicuous bird when not singing.” N. S. Goss (1891) says, “It is very shy and retiring in its habits, and when approached darts from bush to bush, or runs, skulks and hides like mice, and it is no easy matter to flush it from its biding place.”

Both male and female are conspicuous during the courtship chases, but after courtship ceases, only the males are visible until late summer, when the mesquite-covered pastures are suddenly full of streaked young cassin ii. The young chase the adults, calling “tze, tze, tze” all the while. The young are not so reluctant to show themselves as the adults, and as many as a dozen may perch in plain sight in a small area.

Throughout the remainder of the year it is difficult to find a Cassin’s sparrow, even in an area where the species is plentiful, for they spend their lives on the ground, amidst tall grasses. After a cold winter night, when the sun comes up and begins warming the air Cassin’s sparrows may fly to the top of a yucca stalk or a bare mesquite shrub and sit warming themselves for half an hour or more. One cold January morning, just after sun-up, eight Cassin’s sparrows were seen sitting on yucca stalks in a 20-acre grassy field near Midland, Texas. In the afternoon, when the temperature had risen to 500, not a cassinji could be found in that same field.

Probably because of its secretive habits, the species has never been seen dust bathing. Only once was one noted in a water bath: an immature bathed briefly in a puddle left by a lawn sprinkler. It sat low in a shrub and preened briefly after its bath.

Voice: Cassin’s sparrow is known for its exquisitely sweet, haunting song. The song begins with two low, soft notes (seldom heard), followed by a long, loud, high, liquid trill and two shorter descending notes. When the male is defending his territory he gives the song in flight. He flies directly upward for about 20 feet, giving the two low notes as he rises. Then he sets his wings and sings as he floats downward, uttering the two descending notes just before he lights. As he descends, he holds his head up, his tail outspread, and his legs stretched downward. He rarely begins and ends his flight song at the same perch, usually traveling 15 to 30 feet during the downward sail.

Birds that winter in the Midland, Texas area may sing on warm days in early February. First-year birds sometimes begin singing in March before they lose the breast streakings of their first winter plumage. The species does not begin singing regularly until late March. A single male in an area does not begin to sing in flight until a second male enters the area. From April through July their songs are heard incessantly, night and day. H. W. Henshaw (1875) gives a graphic account of Cassin’s sparrow’s song. “J~ * ** possesses an indescribable sweetness and pathos, especially when heard, as is often the case, during the still hours of the night. During a night’s march from Camp Grant to Camp Boxvie, I do not think an interval of five minutes passed unbroken by the song of one of these sparrows. Ere fairly out of hearing of the notes of one performer, the same plaintive strain was taken up by another invisible musician a little farther on, and so it continued till just before dawn.”

Territorial songs are usually not sung from the middle of July to the middle of September. September songs are not always typical, and are delivered more quietly and less frequently than earlier in the summer. During the late summer, a “whisper” song may be heard. It is very soft, and consists of a few preliminary notes and an assortment of trills. The song may continue several minutes, but each phrase is slightly different. The bird seems to be singing to itself, and the song seems to come from a great distance. Several birds in the same locality may sing this song, none of them paying any attention to any other one.

The call note is a loud “tsip.” Another common call is a rapid “tzee, tzee, tzee.” The latter call is used by both male and female during courtship chases, by the young when chasing the parents, and by any wintering bird when it flushes unexpectedly and darts rapidly away from the observer.

Field marks: Cassin’s sparrow is one of the most nondescript of all sparrows. It has no wing bars, eye rings, or tail markings, and the head streakings are so fine as to be almost invisible. Its back is dull gray, and the lighter under parts are unmarked in adults. The long, rounded tail and flat-headed appearance are good field marks. The flat head, combined with the thick bill, gives the bird a sloping profile unusual in the Fringillidae.

Enemies: Herbert Friedmann (1934) lists six records of Cassin’s sparrow victimized by the dwarf cowbird. Margaret M. and Leonard B. Nice (1924) reported “one bird killed accidently by prairie dog poison.” J. Van Tyne and G. M. Sutton (1937) found the remains of a Cassin’s sparrow a shrike had killed and impaled on a yucca leaf. As with most ground nesters, snakes probably are responsible for some loss of eggs and young. The young in a nest near Midland, Texas were found dead and almost completely eaten by large red ants from an ant hill under the nest bush. Whether the ants killed them or started eating them after they were dead from some other cause we could not determine.

Fall and Winter: Cassin’s sparrows withdraw from the northern parts of their range in late October and November. A few winter from southwestern Texas to southeastern Arizona.

Allan R. Phillips (1944) describes the unusual behavior of this species in Arizona in the fall: “The Cassin’s Sparrow appears in Arizona in mid-July as an abundant fall transient, having migrated west from the southern Great Plains. Most of the birds are adults. They are in full song, with testes greatly enlarged, and may go so far as to build nests, but so far as is known they do not complete their nests nor lay any eggs. They decrease sharply in numbers at the beginning of September, but some remain through the winter and leave in early May.”

A. W. Anthony (1892) described this same post-breeding wandering in southwestern New Mexico. He reported that the species appeared in the extreme southwestern portion of Grant County after the August rains and then remained common there until late fall.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Arizona, Colorado and Kansas to central Mexico.

Breeding Range: The Cassin’s sparrow breeds from southeastern Arizona (Santa Catalina Mountains), southwestern New Mexico (Apache, Deming), central Colorado (Barr Lake), central western Kansas (Wallace, Hays), central Oklahoma (Norman), and central and western Texas (Gainesville) south to northern Chihuahua (45 miles south of Villa Ahumada), southern Coahuila (10 miles east of Saltillo), and northern Tamaulipas (Matamoros).

Winter range: Winters from southeastern Arizona (Tucson, Chiricahua Mountains) and western and south central Texas (Frijole, San Antonio) south to southern Sinaloa (Rosario), Guanajuato (Irapuato), and central Nuevo Le6n (Linares).

Casual records: Casu al in southwestern Arizona (Cabeza Prieta Game Range), southern Nevada (Timpahute Valley) and northeastern Texas (Dallas).

Accidental in New Jersey (Island Beach).

Migration: Early dates of spring arrival are: Texas: Rockport, February 24; Midland, April 5. New Mexico: Clayton, May 27. Nevada: Lincoln County, May 26.

Late date of spring departure is: Texas: Lower Rio Grande Valley, April 20.

Early date of fall arrival is: Arizona: Camp Verde, July 21.

Late dates of fall departure are: Oklahoma: -Kenton, September 2. Texas: Rockport, October 4.

Egg dates: Colorado: 1 record, July 14.

New Mexico: 1 record, July 3. Texas: 85 records, April 12 to July 23; 44 records, May 2 to May 29.