As a mostly non-migratory species that is restricted to the boreal forest habitat, Boreal Chickadees just barely occur in a few of the northernmost portions of the U.S. outside of Alaska. Boreal Chickadees are usually quite tame and approachable.

Boreal Chickadees regularly store food, including both seeds and insects, by tucking it into bark or the areas between branches. This stored food is important to them later during the long, cold winters of Alaska and Canada.

On this page

Description of the Boreal Chickadee

BREEDING MALE

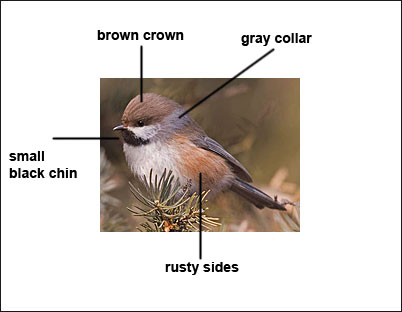

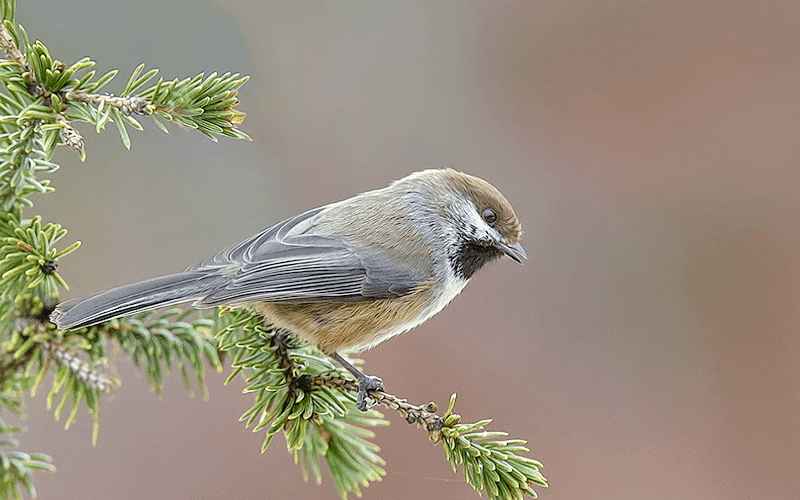

The Boreal Chickadee is small and active like most chickadees, and has a brown cap and black throat separated by white cheeks. Its upperparts and wings are brownish-gray. Brownish flanks line a white belly. Cap darker brown in worn-plumaged adults. Length: 5 in. Wingspan: 8 in.

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

None

Juvenile

Similar to adults.

Habitat

Coniferous forests.

Diet

Consumes insects in the summer, and seeds and insect pupae in the fall and winter.

Photograph © Alan Wilson.

Behavior

Forages on twigs and bark, and may occur in mixed species in flocks during the winter.

Range

Breeds in Alaska, Canada, and parts of the extreme northern U.S. Its population is not well monitored due to its far northern range.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Boreal Chickadee.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

During the nesting season, the female is fed by the male while she is incubating.

Despite its small size, this hardy chickadee can survive winters as far north as the Arctic Circle.

Vocalizations

Song is a simple trill, while calls can be a nasal “tseek-a-jay-jay” or a single “dee.”

Similar Species

All other chickadees (except gray-headed) have black or blackish caps.

Chestnut-backed Chickadee

The Chestnut-backed Chickadee has a rusty back and dark gray to black head, black bib is larger than on Boreal Chickadee.

Black-capped Chickadee

The Black-capped Chickadee has black cap and large white collar.

Nesting

Nests in a natural cavity or old woodpecker cavity. Nest is constructed of moss, lichens, and strips of bark, and is lined with feathers or hair.

Number: Usually 5-8.

Color: White with a few fine markings.

Incubation and fledging:

Young hatch at about 13-14 days and fledge at about 18 days, though continuing to associate with parents for some time.

Bent Life History of the Boreal Chickadee

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Boreal Chickadee – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

(Current AOU – Boreal Chickadee)

PARUS HUDSONICUS HUDSONICUS ForsterHABITS

The type race of these brown-capped chickadees was described and named many years ago from specimens taken on the west coast of Hudson Bay, at Severn River. For nearly 100 years it remained the only recognized form of the species. The characters by which other recognized subspecies have been separated will be mentioned under the respective races. This type race has the widest breeding range of the three races recognized in the 1931 Check-list, from northwestern Alaska to Hudson Bay and south to central Manitoba and central Ontario, whence it wanders farther south in winter.

Dr. Joseph Grinnell (1900a) says of its status in the Kotzebue Sound region of Alaska: “At our winter camp on the Kowak this species was common up to the middle of September. After that date and up to the first of April, but one or two at a time were seen and then only at long intervals. Early in September groups of four to seven were noted nearly every day in the spruces around our cabin. * * * Those chickadees observed during the winter were all in the dense willow thickets along Hunt River. They were there quieter and, by nature of their retreat, hard to find. It may have been that at the advent of cold weather all the chickadees left the spruces and betook themselves to the shelter of the willow-brush; but I am rather inclined to believe that there was a partial migration to the southward. By the first of May the chickadees were back again roving through the woods in pairs”

Lee R. Dice (1920) says that in the interior of Alaska “they occur in willows and alders and in white spruce and paper birch forest”

I cannot find that the Hudsonian chickadee differs materially in any of its habits from the better-known Acadian chickadee, to which the reader is referred.

Nesting: Dr. Samuel S. Dickey (MS.) tells of a nest probably of this race that he found while exploring along the Moose River, west of James Bay. It was in “a singular glade, along the moist north terrace of Moose Island. It was hedged in with black spruce trees of moderate size and a natural fence of speckled alder and mountainholly shrubs (Nemopanthus mucronata). The green moss carpet that lay beyond was seen to contain in its midst several short, weathered, barkless spruce stubs, and in the side of one of them a dark hole loomed up. It was about the size of a 25-cent piece. With a stout pocket ax I parted the hard resistant wood opposite the entrance. Thus I could view the interior. It contained a compactly woven nest, in whose cup lay a clutch of six somewhat incubated eggs. The nest was better composed than are those of the eastern chickadees. Its foundation was a mass of dead and also green cedar moss (Hypnum cristatum). Upon this was the soft bed of fur of the snowfoot hare. The eggs were nicely adjusted in the cup in the center of this mass. Further examination of this nest showed that at its base was decayed moss and hair of former nests of other years. Evidently the much worn cavity and entrance had served this pair for many seasons.

“The eggs were light creamy white in ground color and were sprinkled nearly all over the entire shell surface with light reddish brown. They resembled more closely the run of eggs of the winter wren (Nannus hiemalis) than of specimens from other eastern chickadees.’ The stub was 30 inches high, and the entrance to the nest was 18 inches above the bog surface; the cavity was 6 inches deep.

A. D. Henderson has sent me two photographs of nesting stumps of this chickadee. One was an old tamarack stump in a muskeg; the entrance hole was only 572 inches above the moss, and the nest was practically at ground level. The other was a stub in an old cutting, 13 inches high, and the bird was seen to enter through a hole in the ax cut.

Eggs: The eggs are apparently similar to those of the Acadian chickadee. The measurements of 22 eggs average 15.3 by 12.3 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 16.3 by 12.2, 15.4 by 12.7, 14.9 by 12.4, and 15.2 by 11.7 millimeters.

Fall: Frank L. Farley writes to me from Camrose, Alberta: “This species is partially migratory in this latitude. It is a common summer resident of the spruce forests along the foothills of the Rockies and in much of the territory north of the Saskatchewan River. Numbers of them, at the approach of winter, wander south and east to scattered areas of spruce, which persist on the northern exposures of the larger rivers in central Alberta. Here they remain until early in March. It has been noted that these visitors always feed in the higher branches of the spruces, while the black-capped chickadees hunt the lower parts of the trees. During very severe cold spells, when the thermometer shows 5Q0 below zero, I frequently find dead blackcaps in the woods, no doubt as a result of intense cold or inability to secure food, but I have never known the Hudsonian to succumb at such times. They are, no doubt, the hardier of the two species”

Numerous reports of periodic southward migrations of Hudsonian chickadees have been recorded. The latest one comes to me in a letter from 0. E. Devitt, of Toronto, who writes: “In October 1937 a rather remarkable influx of these northern titmice occurred in this area. They were first noted at Nancy Lake, near King, on October 29, by R. D. Ussher; several turned up at Ashbridges Bay, Toronto, on October 31, and on this date I saw several near Bradford and collected a male. This specimen was later submitted to P. A. Taverner, of Ottawa, with the view that it might be the Acadian race. However, it was identified by him as the ‘nigrescens’ type of the brown-headed chickadee (Penthestes hudsonicus hudsonicus). Individuals remained about Nancy Lake well on into the winter”

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Northern North America; not regularly migratory.

The range of the Hudsonian chickadee extends north to northern Alaska (Hunt River, Tanana, White Mountains, and Bern Creek); Yukon (Robinson Camp); Mackenzie (Fort Goodhope, Lake Hardisty, and Fort Rae); northern Manitoba (Lake Du Brochet and Mosquito Point); northern Quebec (Chirno) ; and Labrador (Okkak). East to Labrador (Okkak, Davis Inlet, and Cartxvright) ; Newfoundland (Paynes Cove, St. John’s, and Makinsons Grove); Nova Scotia (Dartmouth and Seal Island); New Hampshire (Washington); and southeastern New York (Big Indian Valley). South to New York (Big Indian Valley) ; possibly Massachusetts (see text) ; possibly Pennsylvania (see text); southern Ontario (Brule Lake and Sayma Lake); northern Michigan (Blaney); northern Wisconsin (Mamie Lake); northern Minnesota (Sandy Lake and Deer River); northern Montana (south fork of Teton River); and southern British Columbia (Schoonover Mountain). West to British Columbia (Schoonover Mountain, Salmon River, and Ninemile Mountain); and Alaska (Houkan, Fort Kenai, Nushagak, Nulato, Kowak River, and Hunt River). The species has been reported in the mountains of eastern Pennsylvania (Laanna and Pocono Lake) during the summer, and it may be found to breed there.

While not regularly migratory there appears to be an occasional fall movement that extends the range in winter south to southern Michigan (Lansing) ; northern Illinois (Waukegan Flats) ; southern Minnesota (Fairmont); and northern North Dakota (Upsilon Lake); Massachusetts; and New York.

As outlined the range is for the entire species, of which four subspecies are recognized. The typical Hudsonian chickadee (P. h. hudsonicus) is found from northern Alaska and Mackenzie southwestward to Ontario; the Columbian chickadee (P. h. columbianus) is found from Montana and Alberta west through British Columbia and Alaska to the Kenai Peninsula; and the Acadian chickadee (P. h. littoralis) occupies that part of the range that, in general, is east of Michigan and Ontario.

The Cascade brown-headed chickadee (P. Jz. cascadcnsis) is apparently confined to the northern Cascade Mountains in Washington.

Egg dates: Alaska: 1 record, June 9.

Alberta: 4 records, May 17 to June 13.

Labrador: 5 records, June 8 to 12.

Manitoba: 5 records, June 2 to 15.

Nova Scotia: 26 records, May 16 to June 9; 14 records; May 29 to June 5.

COLUMBIAN CHICKADEE

PARUS HUDSONICUS COLUMBIANUS Rhoads

This extreme western race of the Hudsonian ~hickadee ranges from the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska, through the Rocky Mountain region of western Canada, southward to southern British Columbia, Alberta, and northern Montana, but the limits of its range are not accurately outlined.

According to Ridgway (1904), it is “similar to P. h. hudsonicus, but slightly darker and less brown above, especially the pileum and hind neck; chin and throat more decidedly black; bill relatively larger”

Nothing seems to have been published on any of the habits of this race, which are probably similar to those of the other races. The type specimen was taken at Field, British Columbia, in the heart of the Canadian Rockies, at an elevation of about 5,000 feet.

ACADIAN CHICKADEE

PARUS HUDSONICUS LITTORALIS Bryant

HABITS

The eastern race of the Hudsonian chickadee breeds in the spruce and balsam forests, north to the limits of these forests, east of Hudson Bay, in Ungava, Labrador, Quebec, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia. The 1931 Check-list says that it breeds south to Maine, “the mountains of northern Vermont and central New Hampshire, and the Adirondacks of New York.” But there is some evidence to indicate that it may breed, at least occasionally, in some of the mountains farther south. It has been seen in June in Plymouth County, Mass., and at least twice during that month in the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania.

As to the Massachusetts evidence, Dr. Arthur P. Chadbourne (1896) wrote many years ago “While ~valking through some dense old: growth pine woods (Pinus strobus and P. rigida) * * * I was greeted by the snarl chee-d~-e-e-s-e-ah of a Hudson Bay Titmouse. . . . The woods in which I saw the Chickadee were only a few rods from a large cedar swamp, said to be a couple of miles wide, which is seldom visited except by lumbermen in ~vinter; and in many portions the original growth of huge white cedars (Cu pressus thvoides) and hemlock (Abies canadensis) has never been cut. In this old timber one seems to be in northern Maine or New Hampshire, instead of in Massachusetts ;: the subdued half twilight of the damp cool forest, with its rocks and fallen t7ees, covered with a rich carpet of green moss and ferns might well tempt this and other northern birds to make it their summer home”

The Pennsylvania evidence is equally suggestive. J. Fletcher Street (1918) found a pair of these chickadees at Pocono Lake on June 17, 1917. “The location was at the edge of a sphagnum swamp amid a dense grove of dwarf spruces. When discovered the birds evidenced considerable excitement and came and scolded within three feet of me”

Regarding the other Pennsylvania record, Thomas D. Burleigh (1918) writes:

In company with Richard C. Harlow, Richard F. Miller and Albert D. McGrew I spent three weeks in the field in the spring of 1917 about La Anna, Pike County, Pa., and June 3, while searching a large sphagnum bog for a nest of the elusive Northern Water-Thrush, two brown-capped chickadees were seen. * * * They showed a preference for a certain part of the bog that we had been floundering through but although several suspicious looking holes were found, we could detect no signs of their nesting. I returned to the spot the next day, and had no difficulty in finding the birds again. This time I spent two hours trailing them but with no success other than leaving with the conviction that they were mated and if not as yet nesting here, would undoubtedly do so. Not satisfied, however, all of us returned the following day and made another attempt but with no more luck though we again found them at the same place. *** The situation in which they were found was typical of that much farther north, being indeed a northern muskeg in every sense of the word, with lichen covered tamarack, deep beds of sphagnum moss and scattered pools”

The localities in which these birds were found in Pennsylvania would match almost exactly the favorite haunts of the species in the north woods of Canada, coniferous forests of spruces, firs, cedars, pines, and larches, especially in the vicinity of peat bogs and muskegs, sometimes mixed with a few small paper birches and mountain-ashes, with a ground cover of sphagnum moss, Lahrador tea, and other northern plants.

The only place where I have ever found the Acadian chickadee really common was on Seal Island, Nova Scotia. This island is situated about 15 miles off the southwest coast and is about 4 miles long; it is divided in the middle by a low stretch of sandy beach and marsh, from which the land rises at both ends and is heavily wooded with a dense forest of small spruces and firs, sometimes growing so closely together as to be nearly impenetrable. These forests, nourished by the fog banks that envelop that coast almost constantly, were rich and luxuriant, thickly carpeted with soft mosses and ferns, the fallen trees, as well as the trunks and branches of the standing trees, supporting a flourishing growth of various mosses and lichens. In these dense and shady retreats, where the trees were often dripping with moisture, were the favorite haunts of Bicknell’s thrushes and Acadian chickadees, the two most conspicuous birds. It was the first week in July and the young of both species were on the wing. We saw the chickadees feeding their young, and, through the kindness of John Crowell, the owner of the island, we were allowed to collect a few specimens.

Courtship: At Averill, Vt., on May 24, 1915, Frederic H. Kennard watched a pair of these chickadees in what seemed to be courtship behavior. His notes state that “the male was very thoughtful and attentive to his little mate, whom he fed frequently. She kept up an almost continuous twittering call, and would flutter her little wings and ruffle her feathers on his near approach. We saw him give her several green cankerworms and many other small bugs; and I saw them copulate once”

Nesting: W. J. Brown writes to me that the Acadian chickadee is fairly well distributed in the County of Matane on the south shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where he has found some ten nests. The lowest nest was one foot from the ground in an old spruce stub in a bog, and the highest elevation was about 8 feet. Out of the ten nests under observation, two had the entrance hole on the top of the stub, facing all kinds of weather, while the others had the hole at the side of a dead stub. All the nests were made of rabbit hair, with some feathers, well put together.

Philipp and Bowdish (1919) record three nests found in New Brunswick as follows: “On June 5, 1917, a nest was found, nearly or quite completed, in a natural cavity in a cedar stump about two feet from the ground. On June 16 the bird was sitting hard on five eggs, and was persuaded to come out only with great difficulty. As she laid no more, this was apparently her full laying. On June 24 a nest containing seven quite small young was found in a knot hole in a small live spruce. On June 13, 1918, another nest with young was found in a cavity in the top of a dead and rotten stub, about ten feet from the ground. This nest was very near the site of the 1917 nest with young, very possibly belonging to the same pair of birds”

Mrs. Eleanor R. Pettingill (1937), with her husband, Dr. Olin S. Pettingill, Jr., had an interesting experience with a family of Acadian chickadees on Grand Manan, New Brunswick. The nest was about 10 feet from the ground in a hole, made perhaps by a hairy woodpecker, in a tall dead spruce stump. The nest contained seven young that were “fitted compactly together on a comfortable bedding of birch-bark shreds and bits of moss. The base of the nest was about 6 inches below the entrance.~~ Aaron C. Bagg (1939) discovered a nest containing young in Somerset County, Maine. He writes:

For some moments the two chickadees flew about nearby, uttering faint scolding notes of alarm and continued to gather insects from the ends of spruce boughs. It was not until I had seated myself and remained quiet that one of the birds flew to a clump of spruce trees, a lone birch and a cedar. Presently the chickadee dropped down low behind the cedar for an instant. Suspecting it might be the nest, I approached and discovered the nesting cavity hidden in the cedar. Fifteen inches above ground the cedar, not over six inches in diameter, divided into two upright branches at an easy angle. Where they joined on the inside, a space fully ten inches in length, the secret lay: an ideal cavity with a narrow opening. Within the nest were young birds well feathered, nearly ready to leave. When I revisited the nest on July 5, they had departed. Search of the vicinity failed to discover any of the fledglings or of their parents. The nesting cavity contained finely shredded cedar peelings and bits of decayed cedar. But the bulk of the nest consisted of moss and deer hair.

Several other nests have been described by other observers, all in very similar situations and made of similar materials. The cavity is often filled with dry or green mosses, bits of lichens, fine strips of the inner bark of cedars and the down from ferns; but the main part of the nest, where the eggs are hatched, is a well-felted bag composed of deer hair and the soft fur of rabbits or other small mammals, making a warm bed for the young.

Eggs: The Acadian chickadee has been known to lay four to nine eggs to a set, but apparently the two extremes are uncommon. The eggs vary in shape from ovate to short-ovate, and some are rather pointed. They have very little or no gloss. They are white and more or less sparingly and unevenly sprinkled with fine dots or small spots of reddish brown, “hazel”; occasionally the spots are concentrated in a ring about the larger end.

The measurements of 40 eggs average 16.0 by 12.2 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 17.4 by 11.6, 15.8 by 12.9, 14.7 by 12.7, and 15.3 by 11.4 millimeters.

Young: We have no definite information on the period of incubation, which is probably about the same as that of other chickadees, or about two weeks; other young chickadees usually remain in the nest 14 to 18 days.

The Pettingills (1937) watched their family of Acadian chickadees on Grand Manan for an entire day, from sunrise to sunset, each taking turns, with the following results:

Both sexes shared equally in the feeding. Frequently they arrived together and one stood by awaiting its turn to feed while its mate entered the hole with food. On several occasions one bird passed the food to its mate returning from the nest who immediately re-entered the nest to carry it below. * * *

During the course of the day the birds fed their young 362 times. The first feeding took place not long after break of day, at 4:46 A.M. One bird was already on the nest, where it had spent the night, when its mate arrived with food. The brooding bird left the nest and permitted its mate to enter and feed. They left the vicinity of the nest together. Before 6 A.M. they fed their young 34 times. During the day the average feedings were 24 times per hour. The last feeding took place at 7 :40 P.M. when the bird, returning with food, entered and remained in the nest to brood.

Plumages: I have seen no very young nestlings of this species, but Mrs. Pettingill (1937) says that the young, when “approximately three days of age,” were naked except for a few wisps of down on their developing tracts, and that their eyes were only partially opened.

The juvenal body plumage is acquired before the young leave the nest, but the wings and tail are not fully grown until later. The color pattern is much like that of the adult, but the colors are duller and paler, and the plumage is softer and less compact. Dr. Dwight (1900) describes it as “above, brownish mouse-gray, the pileum pinkish drabgray. Wings and tail dull slate-gray whitish edged, the coverts edged with pale wood-brown. Below, including suborbital region and auriculars dingy white and washed on the sides and crissum with pale cinnamon, the chin and throat dull black”

He says that the first winter plumage is “acquired by a partial postjuvenal moult, beginning early in August in eastern Canada, which involves the body plumage and wing coverts, but not the rest of the wings nor the tail, young and old becoming practically indistinguishable.” In the first winter plumage the pileum is “darker and the back browner, contrasting but slightly with the cap; the flanks, sides and crissum rich Mars-brown; the black on the throat deeper and the white of the sides of the head and lower parts clearer”

Adults have a complete postnuptial molt in July and August, replacing the decidedly worn, ragged, and somewhat faded plumage of the breeding season with the fresh and more richly colored autumn plumage.

Food: These and other chickadees are among the best conservators of the forest trees that we have. They are very active at all seasons, inspecting the trunks, branches, and twigs of the trees in search of the minute insects that are so injurious and are too small to he noticed by the woodpeckers and other large birds; nothing escapes the chickadees’ keen little eyes. The food of all the species is very similar in character, varying only with the latitude of the habitat of each and the kind of trees it frequents. The Acadian chickadee is essentially a bird of the northern coniferous forests and is especially useful in protecting theï spruces, firs, and pines in these woods. All summer it may be seen carefully inspecting the branches of these trees even to the outermost twigs, often hanging head-downward to search among the bases of the needles, looking for cater-pillars, moths, beetles, and other insects with which to feed its large and growing family. And in the winter it continues the good work by prying into crevices in the bark and searching the branches and twigs for hibernating insects, pupae, or egg clusters; many of the insects thus destroyed are among the worst enemies of the conifers.

Lucien M. Turner says in his Ungava notes: “It is not uncommon to find their beaks covered with gum from the spruce and larch. I accounted for it by supposing that during the summer months, when the gum exudes plentifully and is so soft, many insects adhere to it, and when winter comes the birds search for just such places to obtain the insects”

While visiting New England in fall and winter, and probably at other seasons, this chickadee apparently feeds to some extent on various seeds; it comes occasionally to feeding stations and seems to be fond of fatty foods.

Horace W. Wright (1917) received a letter from Richard M. Marble, of Woodstock, Vt., in which he states that an Acadian chickadee fed at a feeding station from November well into January. Mr. Wright saw some of these birds feeding frequently “upon stalks of golden rod and aster”; and he quotes William Brewster as having seen them “pecking at gray birch seed-cones”

He (Wright, 1914) saw them “picking seeds on the ground” and “picking at the green undeveloped berries of a red cedar”

Behavior: Judging from my limited experience with them on their breeding grounds, I should say that Acadian chickadees are just as tame and confiding as our little blackcaps; we had no trouble in watching them at short range, and they fed their nearly full-grown young within a few feet of us. They are less active than our familiar chickadees, more deliberate in their movements, and less noisy. They were traveling about in small family parties. Some observers have referred to it as shy, hut others have found it almost tame enough to be caught by hand. Oliver L. Austin, Jr. (1932), found that, in Labrador, while occupied with their nesting duties, they are very quiet and unobtrusive.” He continues:

They keep out of sight and are seldom noticed, even by one Io~king for them. I had to hunt, and hunt persistently, to get three specimens at Sandwich Bay, July 16, 1923. But the moment the young leave the nest, usually during the last two weeks in July, the Chickadees alter their demeanor, and the woods suddenly seem overrun with them. Small bands of young and old together, probably parents with their broods, meander inquisitively through the spruce and larch forests amid the clouds of mosquitoes and black flies. Their tameness, in contrast to their previous reticence, is surprising. Their buzzing statements of facts greet you on all sides. They seem to follow you about. Hunting industriously for aphids, they explore every nook and cranny of the larch branch within two feet of your face. Perched upside down, rightside up, in all manner of conceivable and inconceivable attitudes, they regard you perkily with their bright beady eyes, burst suddenly into their commonplace asser-day-day-doy, and flutter past your ear to the next promising branch. At this season you could almost catch them with a butterfly net.

W. J. Brown tells me of an usually tame Acadian chickadee that he saw. An old trapper had a nest of this bird about 15 feet from his back door in a natural cavity in a balsam fir. He had tacked a small branch directly under the entrance hole for a perch. When he tapped the side of the hole the chickadee caine out and alighted on his hand to be fed. The man said that he had fed the bird in this way several times a day for the past ten days and that it would perch on any finger held out to it.

Acadian chickadees may usually flock by themselves, especially in their summer haunts, but they are often seen to join the merry little winter parties of black-capped chickadees, kinglets, nuthatches, and small woodpeckers that roam through the woods at that season. William Brewster (1938) watched such a gathering at Lake Umbagog in January. He says of the behavior of the Acadians: “For a time they kept high up in the tops of some tall balsams working among the cones, apparently extracting and eating the seeds. The Nuthatch was with them here for several minutes, but the Black-cap chickadees remained lower down. The Hudsonians differed from the Black-caps as follows: : they were much less noisy (often passing minutes at a time in absolute silence); they seldom hung head downward; they hopped and flitted among the branches more actively and ceaselessly, spending less time in one place; their shorter tails were less in evidence; they flirted their wings much more with a more nervous, tremulous motion very like that of Kinglets”

Mr. Wright (1917) noted that “Golden-crowned Kinglets have proved to be the closest companions of these Northern Chickadees on many occasions. Indeed, they seem to be their natural associates. Black-capped Chickadees are rather their incidental companions, with whom they occasionally come in touch, but do not habitually move”

Voice: Mv impression of the ordinary note of the Acadian chickadee was that it resembled the corresponding note of the black-capped chickadee, but it was easily recognizable as not so sharp, clear, or lively as that of our more familiar bird; it was fainter, more lisping, hoarser, and more nasal; I wrote it in my notes as chkka-deer-deer, or chicka-~ deer. But I like Mr. Austin’s rendering, asser-day-day-day, as quoted above.

William Brewster (1938) describes it as “a sharp die-day, day, very different from any note of the common Chickadee. * * * The ordinary chirp is much louder and more petulant. Another note frequently heard is a sharp chip, chee-chee, ciiee sometimes preluded by a sharp che-chit or chee-chit-chit.” Again (1906) he writes it “a nasal, drawling tchick, chee-day, day”

A number of observers have heard this chickadee give a sweet, warbling song of three or four notes, and considerable has appeared in print about it. Other equally keen observers have failed to hear it. Aretas A. Saunders writes to me: “I am inclined to think that the brown-capped chickadees have no notes that correspond to the ‘phoebe’ note of the black-capped chickadee. I have seen quite a bit of the Acadian chickadees in the Adirondack Mountains, and Hudsonian chickadees in Montana. but have never heard a song of any kind from them”

Mr. Brewster (1906), after mentioning some published accounts of the song, writes: “I have never heard anything of the kind from the Hudsonian Chickadee, although I am reasonably familiar with that species, having had abundant opportunities for studying its notes and habits in the forests of northern New England where I have met with it on many different occasions and during every month of the year excepting April”

If two such experienced and keen observers have failed to hear the song, it must be of rather rare occurrence.

Townsend and Allen (1907) add to the discussion and quote Dr. Townsend’s description of a song, heard at Cape Breton Island in August 1905: “It was a low, bubbling, warbling song, which I vainly attempted to describe in my notes. It began with a pset or tsee; followed by a sweet but short warble”

Francis H. Allen (1910) gives a number of references to published accounts of the song, and then adds his own observation, made on Mount Moosilauke, N. H., September 29, 1909: “I observed it for some time at close range atid heard it sing again and again. The song was a short one but took two or more forms, one of which I set down at the time as hearing some slight resemblance to the syllables ivissipawiddlee, though this rendering conveys no clear impression of its warbling quality. The final syllable was sometimes trilled and sometimes pure. It seemed to me that the song corresponded exactly to the phoebe song of the Black-capped Chickadee (P. atricapillu.r), hut it was also strangely suggestive of the song of Bicknell’s Thrush ~’ Field ntarks: The Acadian chickadee hears a general resemblance to our common chickadee, but it can be easily recognized by its brown instead oi black cap and by the rich chestnut-brown of the sides and flanks; the black throat patch seems somewhat duller or less conspicuous. Its behavior and its voice are different, especially the latter, which is easily recognized.

Enemies: Chickadees have to be on the watch for all the mammals and birds that prey on small birds, such as small hawks and squirrels, but their eggs and young are usually safe from many nest robbers in their snug retreats. Mrs. Pettingill (1937) writes: “Once during the day a red squirrel appeared in a near-by birch sapling. The Chickadees, on discovering him, were beside themselves with fright. * * * Both birds began to call noisily and to jump from one branch to another, keeping at a safe distance from the animal, but threatening him by making fake darts in his direction. The fact that one of them feigned injury came as a surprise. Perching at first upright on a branch, it suddenly but slowly toppled over backward until it clung upside down on the branch, wings fluttering helplessly. It did not drop to the ground but let go and alighted near-by. This time, on another branch, it seemed to fall over sidewise, nevertheless holding its legs stiff and not letting go.

In the nest examined by Mr. Bagg (1939) were found an adult Protocalliphora, a blood-sucking fly, and several pupae probably of this species, as well as the larvae of some less harmful species of insects. These fly maggots may be, at times, sufficiently numerous to kill not only the very young birds but those nearly fully fledged.

Fall: Most of these northern chickadees remain on or near their breeding grounds all winter, but on certain seasons, at very irregular intervals, there has been a well-marked southward migration into New England and perhaps farther south. Two of the largest incursions were in 1913 and 1916, of which Horace W. Wright (1914 and 1917) has written full accounts. In November 1904 he saw only four birds, but in four different localities. But in the 1913 flight he had the records of over 40 birds, seen by himself and others, in 15 different towns or distinct localities. The 1916 flight seems to have been even heavier and more widely extended, reaching as far south as Staten Island, N. Y. The birds began to appear in October and some remained almost through January. the crest of the wave coming between November 9 and December 10. He referred the birds of the 1916 flight to the supposed Labrador race, nigricans. which is now regarded as the first winter plumage of the species; as all the birds taken seemed to be of this race, it suggests that these southward flights may he made up mainlv of immature birds.

Some of these hirds evidently spent the winter of 1916 and 1917 in New England, or not much farther south. Mr. Wright (1918) gives another full account of the return flight in the spring of 1917; the latest record seems to be of a bird seen at West Roxbury, Mass., on May 18.

CASCADE BROWN-HEADED CHICKADEE

PARUS HUDSONICUS CASCADENSIS A. H. Miller

Dr. Alden H. Miller (1943b), who is responsible for the above names, says that this race “differs from Parus hudsonicu-s columbianus by darker, much sootier pileum (near Chaetura Drab in fresh plumage rather than Bister or Sepia) ; interscapular area somewhat darker and gray of sides of neck darker and more extensive proximally in auricular area; chestnut of sides darker (Prout’s Brown rather than Cinnamon Brown). Size much as in columbianus, although measurements of the small sample available suggest somewhat greater average dimensions for the Cascade population * *

“The race cascadensis is even darker and duller on the pileum than is P. h. littoralis of the eastern seaboard and it is larger and notably longer-billed as are P. h. hudsonicus and P. h. columbianus. The contrast in coloration between ca.scadensis and columbianus is almost as great as that between P. Jr. hudsonius and Parus cinctus ala.~censis, which, although evidently closely related, breed side by side in the Kowak Valley of Alaska.

“Range. Cascadensis is known at present only from the northern Cascade Mountains in the vicinity of Monument 83 on the United States-Canadian boundary in northwestern Okanogan County, Washington”