Blue-winged Warbler populations rise and fall within a region as habitat changes. They require overgrown field, brushy swamps, or forest clearings or edges, and as these areas become more wooded, the Blue-winged Warblers must move elsewhere.

Males arrive on the nesting grounds several days to a week ahead of females, but it is the female who actually chooses the nest site. Blue-winged Warbler nests are frequently parasitized by Brown-headed Cowbirds in parts of the country where cowbirds are common.

On this page

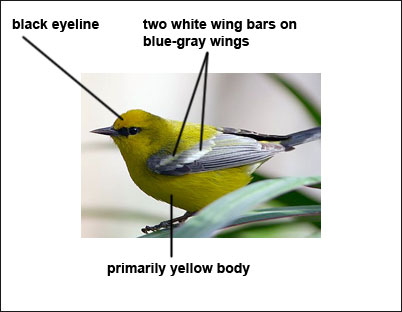

Description of the Blue-winged Warbler

BREEDING MALE

The Blue-winged Warbler is yellowish-green above, with a dark line through the eye, yellow underparts, white undertail coverts, and two white wing bars on bluish-gray wings. The sexes are similar, though the eye line and wing bars are bolder in males. Length: 5 in. Wingspan: 7 in.

Female

The sexes are similar, though females have less pronounced wing bars and eye lines.

Seasonal change in appearance

None.

Juvenile

Immatures are similar to dull adult females.

Habitat

Blue-winged Warblers inhabit brushy areas, overgrown pastures, and woodland edges.

Diet

Blue-winged Warblers eat insects and spiders.

Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Behavior

Blue-winged Warblers forage by gleaning from curled leaves and branch tips.

Range

Blue-winged Warblers breed in parts of the northeastern U.S., Midwest, and South. They winter in Mexico and Central America, and occur across much of the eastern U.S. during migration. The population appears stable, though it has expanded to the north in recent decades and declined in the northeastern U.S.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Blue-winged Warbler.

Fun Facts

Blue-winged Warblers occasionally hybridize with Golden-winged Warblers, producing what are called Brewtser’s Warblers. Subsequent backcrosses can produce the rare Lawrence’s Warbler.

Reforestation in the northeastern U.S. has reduced the amount of early successional habitat favored by Blue-winged Warblers.

Vocalizations

The song is a buzzy ‘Beeee-buzzzz.” A short, buzzy flight call is also given.

Similar Species

Prothonotary Warbler

Prothonotary Warblers lack a black eye line and wing bars.

Yellow Warbler

The Yellow Warbler is yellow overall, lacks black eyeline, does not have obvious white wing bars.

Nesting

The Blue-winged Warbler’s nest is a cup of grasses, leaves, and bark strips lined with finer materials. It is placed on or near the ground, well concealed by grass or vines.

Number: Usually 4-5.

Color: Whitish with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 11-12 days and fledge at about 8-10 days, though remaining dependent on the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Blue-winged Warbler

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Blue-winged Warbler – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

VERMIVORA PINUS (Linnaeus)

Bagg and Eliot (1937) write: “According to Wilson, this species was discovered by William Bartram, who gave it the descriptive name Parus aureus alis caeruleis (Blue-winged Golden Tit), and sent a specimen to ‘Mr. Edwards’ by whom it was drawn and etched. Edwards suspected its identity with the Pine Creeper of Catesby: hence its present inappropriate name, pinus.” As there are other warblers whose wings are more distinctly blue, those of this warbler being only bluish gray, the old familiar name, blue-winged yellow warbler, which stood for many years, seems more appropriate and more truly descriptive.

The blue-winged warbler is a bird of the so-called Carolinian Life Zone, with a rather restricted breeding range in the Central States and not quite reaching our northern borders. Its center of abundance in the breeding season seems to be in southern Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, northern Kentucky, northern Missouri, and southern Iowa. Its range extends northeastward to New Jersey, southeastern New York, and southern Connecticut. It is fairly common in the latter State, and I know of one small colony in eastern Rhode Island within a mile or two of the Massachusetts line. North of these points in New England it occurs only as a straggler or casual breeder. In southern New England I have found it in rather open situations, in neglected pastures where there is low shrubbery, brier patches, and bushy thickets around the edges; or in similar growth along the borders of woods, usually on dry uplands; and sometimes in the rank growth of tall grasses and weeds near the borders of swamps or streams.

Frank L. Burns wrote to Dr. Chapman (1007) of its haunts in Pennsylvania: “This species is here an inhabitant of the rather open swampy thickets, upland clearings, neglected pastures and fence rows, where the grass and weeds have not been- choked out by a too thick growth of briers, bushes, saplings and vines.” Dr. Lawrence H. Wilkrnshaw tells me that, in southern Michigan, “this species loves deep swampy woods, where the golden-winged warbler and cerulean warbler are found.” This is quite different from the haunts iii which we find it in the east, though Dr. Chapman (1907) says: “It is not, as a rule, a deep woods warbler, though I have found it nesting in heavy forest, but prefers rather, bordering second growths, with weedy openings, from which it may follow lines or patches of trees to haunts some distance from the woods.”

Spring: From its winter home in Central America the blue-winged warbler seems to migrate from Yucatan straight across the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf States and along the eastern coast of Texas to Louisiana. It is apparently very rare anywhere in Florida or the Keys, and along the Atlantic coast, where it is comparatively rare, it is found at low elevations. It migrates northward mainly west of the Alleghenies, seeming to avoid the mountains; the main body of the species seems to travel through the Mississippi Valley to the centers of abundance in the central States. Perhaps the birds that settle in southern New York and New England travel up the Ohio River, drifting through Pennsylvania and New Jersey to their destination. According to Milton B. Trautman (1940) this warbler seems to be a rare or uncommon spring migrant in central Ohio, and “in some migrations only 2 individuals were noted” at Buckeye Lake; this adds support to the theory that the birds follow the river along the southern border of the State.

Nesting: Although Wilson (1831) gave a very good description of the nest of the blue-winged yellow warbler, very little was known of its nesting in southern New England prior to about 1880, when nests were found in southern Connecticut, where it is now known to be a fairly common breeder. I found two nests near West Haven, Conn., on June 3, 1910; both were close to the ground but not quite on it; one was in a clump of blackberry vines, weeds, and grasses, in a swampy corner of a scrubby lot; the other was in a bunch of grass and rank weeds on some sprout land among some mixed bushes. Again, on June 1, 1934, I photographed (p1. 12) a nest near Hadlyme, Conn., on the edge of an open, neglected field and close to the border of some young woods. It was built among and attached to the upright stems of a clump of tall goldenrod. These were all typical of the nests described below.

Massachusetts nests are very rare; Forbush (1929) gives but two nesting records for this State, and only one for Rhode Island, though I am confident that its breeds regularly in the latter State. Horace W. Wright (1909b) gives a very full account of a nest found near Sudhury, Mass., in some mixed woods, placed between the exposed roots of a decayed stump and partially concealed by a growth of ferns.

T. E. McMullen has sent me the data for several Pennsylvania nests, three in old fields, one under a cherry sprout, one under a small bush, and one 6 inches up in a tussock of goldenrod; another was under a birch sprout along the edge of an old woods road.

The nest of the blue-winged warbler is unique and quite distinctive, often shaped like an inverted cone, usually very narrow and very deep and supported by a firm cup of strong, dead leaves. I cannot improve on the excellent description given to Dr. Chapman (1907) by Frank L. Burns as follows:

Outwardly composed of the broad blades of a coarse grass, the dead leaves of the maple, beech, chestaut, cherry and oak trees; the leaf points curving upward and inward forming a deep cuplike nest in which the bird’s head and tail seem almost to meet over her back. Occasionally grass stems, coarse strips or wild grapevine hark, shreds of corn fodder, and fragments of beech and wild cherry bark appear in the make-up. Lined most frequently with wild grapevine bark laid across, instead of bent around in a circle, shredded finest oa top, to which is added an occasional long black horse-hair or split grass stem, with now and then a final lining of split grass stems in place of fine bark. The shape varies In accordance to situation, outwardly a short cornucopia, a round basket, and once a wall-pocket affair, would best describe the shapes I have noticed.

Eggs: From 4 to 7 eggs may be found in the nest of the blue-winged warbler; S seems to be the commonest number, and sets of 6 are not very rare. The eggs are ovate, with a tendency to short ovate, and they have only a slight gloss. The white ground color is finely speckled or sparingly spotted with “chestnut brown,’~ “mummy brown,” and “sayal brown,” with under markings in shades of “drabgray.” Some sets have three or four eggs that are almost immaculate, with one egg sparingly spotted; other sets occasionally are prominently spotted with “drab-gray,” “light Quaker drab,” and “dark vinaceous-drab,” or, less often, with spots of dark “mummy brown.” Usually the majority of the markings are confined to the large end. The measurements of 50 eggs average 15.7 by 12.5 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 16.8 by 13.0 and 14.2 by 11.6 millimeters (Harris).

Young: An egg is laid each day until the set is complete, and incubation generally begins when the last egg is laid. The period of incubation is 10 or 11 days, and the young remain in the nest from 8 to 10 days. Mr. Burns gave Dr. Chapman (1907) the following full account of the nest life:

The task of Incubation falls on the female alone. It appears that an airing is taken in the early morning or a little before midday, and again in the early evening, though perhaps not regularly every day. I have not seen the male about the nest with food at this period. The female will allow a close approach, looking Into one’s eyes with that hunted look so common in wild animals, and often flushing without a protesting note. The period of incubation In the one instance was exactly ten days.

On June 13, at 6.30 p. in., five young just hatched were blind, naked and prostrate from chin to sternum. The shells were disposed of immediately, in what manner I am unable to state; the female was reluctant to vacate.

On June 15, at 2.45 p. in., the young were able to raise their heads slightly and a fluffy bit of down had appeared about the head, also a dark stripe along the back hone. The female appeared, accompanied by the male, and fed the young with small green larvae: such as may be found on the under-side of oak and chestnut leaves: and then shielded the callow young from the hot rays of the sun.

On June 16, at 6.30 p. in., when the young were three days old, a downy puff appeared between the shoulders, wing Quills being dark. The strongest bird had the eyes partly open and the mouth wide open for food.

On June 18, at 7 p. in., the heads and bodies were no longer flesh-colored but were well enough covered to appear dark. The eyes were open. At a cluck from me their mouths flew open. Both parents fed them with green-colored larvae. When the male rested a moment on a brier above the nest, the female flew down and drove him away, fed the young, re-appearIng with excrement in her beak, which was carried in an opposIte direction from the regular approach via maple bough and poplar sapling. The male fed the young from a mouthful of very minute larvae or eggs, which were gathered from the silken nests in the unfolding leaves of a nearby poplar; after this (7.30 p. in.) the female covered the young for the night.

On June 20, at from 6.50 to 7.35 p. in., the young had been seven days in the nest. They were well feathered and of a yellowish-green cast, the short tails being tipped with yellow. The parents were more suspicious. The female came to the maple bough with something in her beak and flew down to the briers and back again several times before she dropped to the edge of the nest and fed her young. The male appeared immediately but swallowed a green grub himself upon discovery of me twenty-five feet away. The female came again in five minutes with a brownish object in her bill, but appeared more timid and refused to drop to the nest until the male set her an example of courage.

On June 21, at 6.12 p. in., the young were fully fledged in green plumage above and dirty yellow beneath. They showed fear of me for the first time, eyeing me in the same manner as the parent bird when on the nest. They were evidently ready to vacate at a moment’s notice or hasty movement on my part. The parents appeared, scolding rapidly. The female fed the young as soon as I retired to my old stand under a bush, with a rather large green grub (6.20 p. in.) and flew out to the top of a blackberry bush, followed immediately by the topmost fledgling. It could do little more than run. The adults flew to within a yard of my head, making a great outcry, and in the midst of the excitement the remainder of the young vacated the nest with feeble chips. The male gave his attention to them, while the female followed me as I beat a hasty retreat to enable them to collect their little family before dark. Eight days had elapsed since incubation was completed, and it is not at all unusual for the young of this species to leave the nest while so tiny and ragged.

Plumages: Dr. Dwight (1900) calls the natal down “mouse-gray,” and describes the juvenal plumage, in which the sexes are alike, as, “entire body plumage olive-yellow darkest on the back and throat. Wings and tail slate-gray largely edged with plumbeous gray, the tertiaries and coverts with olive-yellow; the greater and median coverts tipped with white, yellow tinged. Ilectrices largely white. Lores dusky.”

A partial postjuvenal molt begins early in July, involving the contour plumage and the wing coverts, but not the rest of the wings or the tail. This molt produces the first winter plumage in which the sexes are very much alike, the female being duller in color, especially the streak through the eye, and having less yellow on the crown. Dr. Dwight (1900) describes the first winter male as “above, bright olivegreen, lemon-yellow on the crown veiled by greenish tips. Below, bright lemon-yellow, the crissurn white or merely tinged with yellow. Transocular streak black. Wing coverts plumbeous gray, edged with olive-green, the greater and median tipped with white, yellow tinged, forming two broad wing-bands.”

The birds are now practically adult in plumage. The first and subsequent nuptial plumages are acquired by wear, which produces little change beyond removal of the greenish tips. Subsequent winter plumages are acquired by a complete postnuptial molt each July.

The interesting hybrids between this and the golden-winged warbler are discussed on pages 3 and 4. Kumlien and Hollister (1903) mention a probable mating of this with the Nashville warbler.

Food: Nothing seems to have been published on the food of the blue-winged warbler beyond that mentioned above as food given to the young, which is doubtless eaten by the adults as well. It is apparently wholly insectivorous, seeking its food near the ground in the weed patches and underbrush where it lives and among the lower branches of the trees in its haunts. Probably any small insects that it can find in such places, as well as their larvae and eggs, including many small caterpillars, are eaten. Small grasshoppers and spiders. are probably included. Prof. Aughey (1878) observed it catching small locusts in Nebraska. It is evidently a harmless and a very useful bird in destroying insects that are injurious to foliage.

Behavior: Dr. Chapman (1007) writes: “It is rather deliberate in movements for a Warbler, and is less of a flutterer than the average member of the genus Dendroica. Some of its motions suggest those of the tree-inhabiting Vireos, while at times, as the bird hangs downward from some cocoon it is investigating, one is reminded of a Chickadee.” And he quotes Burns as follows:

Perched lnconspicuously near the top and well out on the branchiets of a tree or sapling, preferably facing an opening, if in a thicket; it is in Itself so minute an object as to be passed unseen by many, more especially as it is much less active than most of our Warbiers. With body feathers puffed out to a delightful plumpness, except for the backward sweep of the head while in the act of singing, It remains motionless for quite a while. When it moves it Is with a combination of nervous haste and deliberation, and Its song may be heard from quite another part of the landscape with no apparent reason for the change. While It has its favorite song perches, It is quite a wanderer and not Infrequently sings beyond possible hearing of Its brooding mate, but oftener within fifty to two hundred feet of the nest.

Voice: Aretas A. Saunders contributes the following study of the songs of this warbler: “The territory song of the blue-winged warbler consists of two long, buzz-like notes, the second usually lower in pitch than the first and rougher in sound, bzzz2zzz: brrrrrr’n~. The pitch interval between the two notes varies from one tone to four and a half tones, but the smaller intervals, one tone and one and a half tones, are much commoner. The second note is lower in pitch than the first in about 75 percent of my records, and higher in most of the others. In a few songs the second buzz is a double note, and one may hear both lower and higher notes from a medium distance, only the lower from a greater distance, and only the higher when very near the bird.

“The pitch is not high as compared to other warblers, ranging from C’ ‘ ‘to D ””,one tone more than an octave. The territory song commonly begins on some note from A’ ‘ ‘ to C ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘. It varies in time from 1i/~ to 1% seconds, the first note being either equal to or shorter than the second. The second note is often twice as long as the first. In some songs the second note is broken into two notes, and in one record it is in four short notes, so that the song is essentially like that of the golden-winged warbler.

“After the birds have been on the breeding grounds for a week or two, singing of the nesting song begins. This song has the same buzzlike quality as the other, but it is exceedingly variable, considerably longer, and hardly ever twice alike. The song often begins with a series of short notes, like tsit tsit tsit, or contains such notes somewhere in the middle. There are usually long buzzes that change pitch by slurring upward or downward. On one occasion, I found a bird that sang a territory song and four different nesting songs. Often the nesting song is sung in flight. By June this song is heard about as frequently as the territory song, and in late summer, after the molt, it is the one most commonly heard.

“The song of this bird is heard from its arrival in spring until early July, when it ceases for a time. It is usually revived in late July or early August, and from then on may be heard fairly frequently until the birds depart about the last of August.”

In his notes sent to Dr. Chapman, Burns describes the song as, “a drowsy, locust-like, .swe-e-e-e-e ze-e-e-e-e, the first apparently inhaled and the last exhaled. * * * Another song heard on the first day of arrival, on one occasion, uttered by several males in company, possibly transients here, and may be the mating song, suggests the Chickadee’s che-de-de-e, clie-dee-e, and clie-de-de-dee, uttered repeatedly in one form or other in excitement, and while running out on the branchlets. The call and alarm note is a rather weak ckip.” Dr. Chapman (1912) records a longer song, heard later in the season as “w~-cki-chi-chi-c1d, ck~Th, ch~-ckilr.”

Francis II. Allen tells me that the final note, ~e-e-e-e-e, as rendered by Burns, “is really a very rapid series of pipe, as if the bird had lips like ours and vibrated them by forcing the air through them: in other words, giving a sort of avian Bronx cheer, but high in pitch.

The individual pip notes are clear, but the effect of the rapid succession is somewhat buzzy.”

The songs of the hybrid forms may be like the song of either parent form, more often like that of the goldenwing, or a mixture of the two.

The flight song, as heard by Frank A. Pitelka, is recorded as follows:

taee tzip zee-zee-zee-zee-zee-zee- zee-z~e-zee-zee-zee-zee

The song of the blue-winged warbler is one of the high-frequency songs; Albert R. Brand (1938) gives the approximate mean as 7,675, the highest note about 8,050 and the lowest note about 7,125 vibrations per second; this compares with an approximate mean for the blackpoll warbler of 8,900 vibrations per second, the highest frequency of any of the wood warblers, and an average for all passerine birds of about 4,000 vibrations per second.

Field marks: A small warbler with a greenish olive back, yellow forehead and under parts, with a black line through the eye and two white wing bars, is a blue-winged warbler. The female is merely more dull in coloration than the male, and the young even duller. The hybrids between this and the golden-winged warbler are more puzzling, but in a general way they can be recognized; a nearly typical blue-winged warbler with a black throat is probably a Lawrence’s warbler; and a golden-winged warbler without a black throat or cheek and with a variable amount of white and yellow on the under parts and in the wing-bars, is probably a Brewster’s warbler. But there is an immense amount of individual variation between the two species, due to frequent crossing.

Fall: Most of the blue-winged warblers move southward during August and September, though a few may linger in the southern part of the breeding range into October. Professor Cooke (1904) says: “Most of the individuals of the species migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, apparently avoiding Florida on the east and Texas and Vera Cruz on the west, as there is no record of the occurrence of this warbler in fall in Texas, and but one in Florida: that of a bird taken at Key West August 30, 1887.” But this remains to be proved.

Alexander F. Skutch writes to me: “This is another very rare migrant in Central America. It has been recorded only a few times in Guatemala and apparently not at all in Costa Rica. I have seen it only once, on the Finca Mock, Guatemala, on October 30, 1934.”

Very little seems to be known about its winter distribution and still less about its winter habits.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Eastern United States to Panamd.

Breeding range: The blue-winged warbler breeds north to southeastern Minnesota (Lanesboro); southern Wisconsin (Mazomanie, Prairie du Sac, and Glarus); northeastern Illinois (Rockford, Deerfield, and La Grange); southern Michigan (possibly Hastings, and Ann Arbor); northern Ohio (Toledo, Lakeside, Cleveland, and Austinburg); southern Pennsylvania (Carlisle); southern New York (Ossining and Whaley Lake); and Massachusetts (Springfield and Sudbury). East to eastern Massachusetts (Sudbury and Lexington); Connecticut (Westfield and Saybrook); Long Island (Mastic and Oyster Bay); New Jersey (Demarest, Morristown, and Elizabeth) ; southeastern Pennsylvania (Tinicuin and Berwyn); probably occasionally in northern Maryland (Cecil County and Sabillasville); eastern and central Ohio (Canfield and Columbus) ; east-central Kentucky (Berea); central Tennessee (Nashville and Fall Creek); and central northern Georgia (Young Harris). South to northern Georgia (Young Harris, Margret, and Atlanta); northeastern Alabama (Long Island); central Tennessee (Wildersville); and northwestern Arkansas (Pettigrew and Winslow). West to northwestern Arkansas (Winslow and Fayetteville) ; west-central Iowa (Warrensburg); eastern Iowa (Lacey, Grinnell, Winthrop, and McGregor); and southeastern Minnesota (Lanesboro). The blue-winged warbler has occurred in summer west to eastern Kansas (Emporia and Leavenworth); central-southern and eastern Nebraska (Red Cloud, Plattsmouth, and Omaha) ; western Iowa (Sioux City) ; and north to Minnesota (Minneapolis); southern Ontario (Point Pelee, Strathroy, and West Lake) ; central New York (Penn Yan and Auburn) ; and southern New Hampshire (Manchester).

Winter range: The principal winter home of the blue-winged warbler seems to be in Guatemala, though it has been recorded in winter from the Valley of Mexico; Puebla (Metlatoyuca); Veracruz (Tres Zapotes) ; to eastern Nicaragua (Rio Escondido and Greytown). There is one winter record each from Costa Rica (Bonilla), Panamfi (Port Antonio), and Colombia (Santa Marta Region).

On January 6, 1900, a dead blue-winged warbler (apparently dead from starvation) was picked up in Bronx Park, New York. It had only recently died and in all probability was the bird seen on December 10, in the same region.

Migration: L ate dates of spring departure are: Colombia: Santa Marta Region, March 21. Veracruz: Jalapa, April 7. Florida: Pensacola, April 25. Alabaina: Guntersville, May 2. District of Columbia: Washington, May 30. Louisiana: Monroe, April 27. Texas: San Antonio, May 12.

Early dates of spring arrival are: Florida: Pensacola, April 4. Alabama: Shelby, April 4. Georgia: Atlanta, March 20. North Carolina: Arden, April 18. District of Columbia: Washington, April 23. West Virginia: Wheeling, April 23. Pennsylvania: Germantown, April 25. New York: Yonkers, April 26. Massachusetts: Lexington, May 6. Mississippi: Bay St. Louis, March 13. Louisiana: New Orleans, March 23. Arkansas: Winslow, April 2. Tennessee: Nashville, April 7. Kentucky: Eubank, April 10. Illinois: Springfield, April 29. Ohio: Columbus, April 22. Michigan: Ann Arbor, May 1. Missouri: St. Louis, April 17. lowa: Grinnell, April 28. Wisconsin: Reedsburg, April 30. Minnesota: Lanesboro, May 7. Texas: Cove, March 27. Kansas: Onaga, April 20.

Late dates of fall departure are: Minnesota: Lanesboro, September 1. Wisconsin: Elkhorn, September 19. lowa: Giard, September 20. Missouri: Monteer, September 17. ~~rI~ans~: Winslow, September 18. Louisiana: Monroe, October 7. Michigan~ackson, September 13. Ohio: Oberlin, September 27. Indiana: Bloomington, September 28. Illinois: Chicago, September 29. Kentucky: Bowling Green, October 5. Tennessee: Memphis, September 11. Mississippi: D~er Island, October 13. Massachusetts: Belmont, September 6. New York: New York City, September 25. Pennsylvania: Jeffersonville, September 19. District of Columbia, Washington, September 14. West Virginia: French Creek, September 28. North Carolina: Reidsville, September 26. South Carolina: Huger, September 10. Georgia: Tifton, September. 27. Florida: St. Marks, October 9.

Early dates of fall arrival are: District of Columbia: Washington, August 13. Georgia: Columbus, July 28. Alabama: Leighton, August 8. Florida: Key West, August 30. Mississippi: Gulfport, August 23. Texas: Cove, July 29. Tamaulipas: Matamoros, August 25. Costa Rica: Bonilla, September 8.

Banding: Few blue-winged warblers have been banded and recovered. A bird banded at Elmhurst, Long Island, on August 17, 1935, flew into a screened porch at Westhury, Long Island, on May 7,1937. The two places are about 15 miles apart.

Egg dates: Connecticut: 30 records, May 25 to June 24; 20 records, May 29 to June 6, indicating the height of the season.

New Jersey: 40 records, May 16 to June 19; 29 records, May 22 to 30.

Pennsylvania: 27 records, May 28 to July 7; 14 records, May 28 to June 3 (Harris).