Even though Bell’s Vireos will aggressively chase female Brown-headed Cowbirds, Bell’s Vireo nests are heavily parasitized by cowbirds. Male vireos sing prolifically, often near or even from the nest.

Bell’s Vireos eat mostly insects during the summer. Small insects are swallowed right away, while large, harder insects are pounded several times with the bird’s beak before they are swallowed.

On this page

Description of the Bell’s Vireo

BREEDING MALE

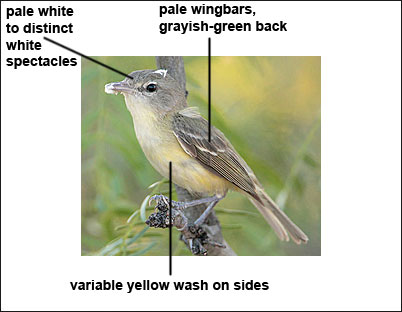

The Bell’s Vireo is a small vireo with grayish to greenish upperparts, white to pale yellow underparts, one bold wing bar, a thin, dark line through the eye, and a white supercilium. Eastern races are more colorful than the grayer western forms.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

None.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to adults.

Habitat

Bell’s Vireos inhabit brushy scrub and streamside thickets.

Diet

Bell’s Vireos eat insects.

Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

Behavior

Bell’s Vireos forage low in bushes.

Range

Bell’s Vireos breed across much of the central and southwestern U.S. They winter in Mexico. The population has declined in recent decades.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Bell’s Vireo.

Fun Facts

Bell’s Vireos are a very common host for the Brown-headed Cowbird, which lays its eggs in the nests of other birds.

Though small and nondescript, the Bell’s Vireo’s distinctive song gives away its presence.

Vocalizations

Calls include a nasal “chee,” while the song consists of a musical jumble of notes.

Similar Species

Hutton’s Vireo

The Hutton’s Vireo lacks the eye lines of the Bell’s Vireo.

Nesting

The Bell’s Vireo’s nest is a cup of grass, weeds, and other plant materials, is lined with soft materials, and is placed on a forked twig about 3 feet off the ground.

Number: usually lay 3-5.

Color: White in color with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 14 days, and begin to fly in about another 2 weeks, though continuing to associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Bell’s Vireo

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Bell’s Vireo – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

VIREO BELLI BELLI Audubon

Audubon (1844) discovered this species on his Missouri River expedition and named it in honor of his companion J. G. Bell, who procured the type specimen on the same day that Harris’s sparrow was discovered, May 4, 1843. He says of its haunts: “This species, like other Vireos of the smaller class, is usually found in the bottom lands along the shores of the Upper Missouri river, from the neighbourhood of the Black Snake Hills as far as we went up that river; finding it in many instances, whether in the bottom lands, overgrown with low shrubbery, or along the borders of ravines that discharge the water accumulating during the spring meltings of the snows that cover the upper country prairie land.”

The species, Vireo belli, is widely distributed over the western United States and northern Mexico, but the type race is found only east of the Rocky Mountains, from southern South Dakota, northern Illinois, and northeastern Indiana to eastern Texas and Tamaulipas.

Like the white-eyed vireo, Bell’s is a denizen of low dense thickets, preferably along the banks of a river or some small stream. Where the ranges of the two species overlap, they are often found in similar haunts or in the same thickets. Bell’s vireo seems to show a preference for thickets of wild plum or small, densely leaved plum trees. But it is also often found in thickets of hazel bushes, alders, haws, willows, or dogwoods, specially those that are overgrown with a tangle of wild grapevines.

In Texas, according to George F. Simmons (1925),its habitats are: “Mesquite flats and mesquite prairie forests; tangled brush and brier patches in open country; mesquite thickets bordering open prairie or cotton fields; lines of bushes and trees along country roads and fence rows between cultivated fields; brush fringing woods or roadsides; osage-orange or bois-d’arc hedges; orchards ; ‘plum thickets on prairie or on country hillside.”

Spring: Of the spring migration in Central America, Dickey and van Rossem (1938) write: “From April 5 to 9, 1927 a marked wave of this species was migrating through the beach scrub and more open parts of the woodland at Barra de Santiago. As the males were then in full song, they were naturally more conspicuous than would otherwise have been the case. Even so, it was obvious that large numbers were passing through, and in the low growth along the peninsula as many as a dozen birds were in sight or sound at one time. The evidence of a fall and spring migration in El Salvador, without the detection of a single winter visitant, argues that some individuals, at least, winter considerably to the southward.”

Nesting: Harold M. Holland, of Galesburg, Ill., writes to me: “During the past 40 years or so, upward of fi hundred nests of Bell’s vireo have been examined by me in this west-central Illinois locality. None of these has contained more than four vireo eggs, which is the normal complement. Fresh eggs have been noted from May 25 to June 15. The characteristic and unmistakable song, when heard in proper season where surroundings offer a favorable site, is indication usually of a nest near at hand.

“Forbush, in the ‘Birds of Massachusetts’ [vol. 3] states that the nest is ‘lined with soft substances, such as down or hair,’ and others have mentioned down and hair. Linings of the nests observed by me could not be even remotely regarded as of soft substances. While occasionally a horsehair may have been worked into the lining, neither plant down, poplar, nor willow ‘cotton’, nor similar materials, though often easily available, have been included.

“Typical nests of this locality may be described as composed exteriorly of soft, grayish plant strips and shreds, fibers, leaf fragments, and small pieces of bark, neatly lined almost invariably with fine, brownish grass stems. The exterior, especially at the rim, as well as the lining, may be supplemented by spider web and cocoons.

“Two nests before me provide fair examples of measurements: (1) exterior diameter, 2% by 3 inches; interior diameter, 11/2 by 134 inches; exterior depth, 33/s inches; interior depth, 11/2 inches. (2) exterior diameter, 3 inches; interior diameter, 134 by 17/s inches; exterior depth, 3 inches; interior depth, 11/4 to 134 inches.”

Many years ago, A. Dawes Du Bois sent me some notes on Bell’s vireo. On June 5, 1913, he watched a pair of these vireos near Lincoln, Ill., “in a raspberry patch adjoining an orchard and thus located their nest, which was fastened to a raspberry stalk about 2 feet from the ground. The little twig, which had formed one prong of the fork in which the nest was originally built, had broken loose so that the nest hung from one side only, and the four eggs were not very secure in a wind. Beneath the nest on the ground was the empty shell of a fresh cowbird’s egg, about one third of it, at the large end, broken away as if by the bill of a bird. I suspect that the vireos had thrown it out.” He took this nest and the eggs, but the birds built another nest and raised a brood in the same raspberry patch; they had fully grown young on July 21.

Some years later, Mr. Du Bois (1940) published an account of this and two other nests, which he found near Springfield, Ill., in 1922 and 1923. One of these “was two and a half feet from the ground, in a haw bush at the edge of a brier patch.” It “was composed of bark shreds, plant fibers, numerous thin, paperlike dried leaves, and some bits of newspaper; lined with fine grass stems and a very few coarse hairs.” One of the others “was three feet from the ground, exceedingly well hidden, in a bushy wild crab, in a narrow but dense thicket.” It was similar in construction.

Pitelka and Koestner (1942) made a study of five nests of Bell’s vireo in central Illinois. “These consisted of three attempts at nesting and a fourth successful nesting of one pair together with one successful nesting of a second pair. Nest building lasted 4 to 5 days. * * * Cowbird interference was probably the cause of desertion of the first two, and possibly three, nests of one pair. At each of these nests, desertion occurred after removal of one host egg. Nest building was done by the female.”

In 1926 Mrs. Nice (1929) followed the fortunes of a pair of Bell’s vireos for two months on the campus of the University of Oklahoma; they built three nests, all of which were destroyed by a cat, in one case after the young had hatched and in the other two cases while there were eggs in the nests. The first nest was in a honeysuckle bush, 15 inches from the ground; it “was largely made of birch bark (from an introduced tree near-by) ; spider webs, cocoons and bark fibres were on the outside, while fine pieces of peppergrass stems and horse hair served as lining.” This nest was destroyed on June 3 or 4, and by the 14th the birds had built a new nest and laid four eggs; this second nest was 75 yards away, three feet from the ground, in a hydrangea bush in a row of bushes. On June 25, this, nest had been torn out. The next day she “discovered that the foolish little birds had returned to their first bush and had started a nest three feet from the ground.” On July 2, the first egg had been laid, but a similar disaster befell this third attempt three days later.

In Texas, Mr. Simmons (1925) records nests as placed from “1.12 to 10, once 25, average 3, feet from ground.” He says that the nest is “nearly always in a low mesquite tree; occasionally in cedar elm, winged elm, Texas black-fruited persimmon, Mississippi hackberry; black willow, prickly ash; honey locust, or bois d’arc bush.” He adds the following to the usual materials employed: “Bits of wool; rarely, tiny bits of twigs, rootlets, Indian tobacco weed, feathers, cast-off snake-skin, string, lichens, moss, bits of cotton, rags, and pieces of wasp nest. * * * Occasionally nests have false bottoms built over eggs of the Dwarf Cowbird, the birds preferring a second story to building a new home.”

In addition to the above-mentioned situations, nests have been recorded in cottonwood, dogwood, and apple trees, in lilac, osageorange and hazel bushes; and doubtless other kinds of trees and bushes are used as nesting sites; niost of the nests have been less than 5 feet above ground, much less on the average.

Two very unusual nests are worth mentioning. George W. Morse, of Tulsa, Okla. (1927), reports a double nest, the second having been built two-thirds of the way around the first and containing two eggs while the young were still in the first nest and nearly ready to fly; the second nest later contained four eggs, when he collected it. Baird, Brewer, and Ridgway (1874) report a nest, taken by B. F. Goss, near Neosho Falls, Kans., which, “unlike others of this family, is lined with down, and the fine long hair of some animals, ihstead of with vegetable stems.” With the exception of a similar statement by Forbush (1929), probably based on the same authority, I can find no mention of such a lining in all the many references to this species in the literature.

Eggs: Bell’s vireo lays three to five eggs to a set, but four seems to be the commonest number. Those that I have seen are ovate, or somewhat pointed ovate, and lusterless white, with a few fine dots of dark brown or blackish, scattered mainly about the larger ends. Others have reported spots of lighter brown or reddish brown. Some eggs, and apparently some entire sets, are nearly or quite spotless. Rarely, an egg is more heavily spotted. The measurements of 50 eggs average 17.4 by 12.6 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 18.8 by 12.7, 17.0 by 13.2, 16.5 by 11.9, and 16.8 by 11.4 millimeters.

Young: AIl observers seem to agree that incubation normally lasts for about 14 days, and that this duty is shared by both sexes. Pitelka and Koestner (1942) found that “incubation began after laying of the first egg and lasted 14 days. Nestling life lasted 11 days. * * * Both sexes participated in incubation and care of young.” Mrs. Nice (1929) states that in one of her nests there were four eggs on May 15, there having been only one egg on May 12; “three of these hatched May 28, the last, May 29; hence, incubation must have started with the third egg and lasted 14 days.” Of the feeding of the young, she says:

The meals were brought at a rapid rate, once every 4.9 minutes during five and a half hours of watching. To be sure, some of these 75 meals, at least five and perhaps a dozen, went into the female’s crop, so that the young received food once every five minutes on an average, or three times an hour for each little bird. The male fed 54 times, the female 21. * ï ï In this fragmentary study of the home life of a pair of Bell Vireos, the enthusiasm of the male throughout the cycle was delightful to witness: Ms Intense interest in nest building, his exuberance while incubating, and his devotion to the young both in occasionally brooding them and in assuming the major part of the task of feeding them. * * * The average duration of brooding was 13 minutes on the part of the female and three for the male. Both parents ate the feces the third and fourth days and carried them away after that, the female disposing of seven in the five hours, the male of eight.

Mr. Du Bois (1940) says that during an “hour and forty-four minutes of watching, the young were fed seven (or possibly eight) times, mainly with smooth caterpillars; they were examined on four occasions without being fed, and were twice brooded. * * * Both birds stood at the fork side of the nest, on one branchlet or the other (never on the unsupported edge), to inspect or to feed.” He continues:

The newly hatched young were of a pinkish or reddish color. When one day old they remained entirely naked. Examination through a reading glass disclosed no trace of down or filament on any part of the reddish flesh-colored skin. The lining of the oral cavity was slightly yellowish, without markings. The wings were slender but relatively rather long.

At the age of five and a half days, though the nestlings had grown much larger, their eyes did not appear to have opened, and they continued to be almost naked. A narrow blackish tract bad started along the anterior portion of the median ilne of the back, adjacent to the neck; edge of wing was thickly sprouted; and there was slight indication of sprouting on crown and hind head, and in the caudal tract. Nothing on rump or posterior portion of back. Under parts showed barely an indication of broad, extensive tracts along the aides, these showing whitish rather than blackish. At this age one of the nestlings demonstrated a lusty voice for so small a creature: a squeaking noise.

Plumages: According to Ridgway (1904), the young Bell’s vireo in juvenal Plumage is much like the adult, “but pileam and hindneck soft drab, back and scapulars dark drab, under parts nearly pure white, with sides, flanks, and under tail-coverts tinged with sulphur yellow, wing-bands more distinct, and tertials edged with yellowish white or pale sulphur yellow.”

Apparently the molts are similar to those of other closely related vireos, a partial postjuvenal molt in July and August, no prenuptial molt, and a complete postnuptial molt late in summer.

Food: Dr. Edward A. Chapin’s (1925) report on the summer food of the Bell vireos, was based on the examination of 52 stomachs, collected from May to August, inclusive. “Nearly all (99.3 per cent) of the food taken is of animal origin, such forms as bugs, beetles, caterpillars, and grasshoppers predominating.” Hemiptera (bugs) make up 34.43 percent of the summer food. Of Orthoptera, the average percentage is 18.52. Dr. Chapin continues:

No other species of vireo of which the food habits are known takes so large a quantity of such bulky insects as grasshoppers, locusts, and the like. Though the present species is one of the smallest in size, it includes in its diet for July enough of the orthopteroids to make 34.88 per cent of that month’s food. * * * About one-fifth (20.63 per cent) of the subsistence of the Bell vireos during the summer Is made up of caterpillars, and of adult moths and butterflies, and their eggs. As the last-named items are rarely found In a stomach, the figures given refer mainly to the first two. * * * Beetles of all kinds make up 15.26 per cent of the summer food of the Bell vireos. Ladybird beetles are taken In moderate numbers and form 2.19 per cent of the total food. Weevils (6.09 per cent) and leafbeetles (3.98 per cent) account for most of the remainder of coleopterous food. * * * Hyinenopterans of all sorts (bees, wasps, etc.) amount to 6.44 per cent of the total diet. * * * The rest of the animal food of the Bell vireos is composed of a few miscellaneous Insects and spiders and a very few snails, spiders (2.71 per cent) being the most Important. * * It Is not until July that the Bell vireos feed on wild fruits. At that time 1.57 per cent of the subsistence is of vegetable matter.

In his summary, he remarks: “Grasshoppers, locusts, caterpillars, and moths are frequently injurious to man’s best interests, as also are many of the hemipterans. The percentage of these insects in the food of birds of this species is 73.58, nearly three-fourths of the total. Of the remainder about half the beetles and hymenopterans are injurious. This will add about 11 percent, leaving about 16 percent of the food of debatable import. As the small quantity of vegetable matter eaten is of no economic significance it may be disregarded. Ladybird beetles are about the only beneficial forms that the birds take, and these are not consumed in very great numbers.”

Behavior: Ordinarily Bell’s vireo is a timid, shy, retiring little bird, but when incubating, brooding, or feeding its young it shows considerable fearlessness, coming freely to the nest even in the near presence of an intruder; it has somtimes been touched by the human hand while bravely defending its eggs or young. The male is quite as devoted as the female, and generally remains near his incubating mate, singing joyously in the same bush or in one nearby. But, at other times, this vireo is active and restless, disappearing into its leafy retreats on the least alarm; it jumps and flits about in the bushes so rapidly that it is difficult to catch a glimpse of it, though it may be watching the observer from behind some sheltering foliage. Its actions remind us of that other dweller in low shrubbery, the whiteeyed vireo. It is often found in similar thickets with the white-eye, or with the black-capped vireo in Oklahoma or Texas, where the ranges of these species overlap. As Pitelka and Koestner (1942) say, “individuals are seldom seen above six or seven feet in shrubby vegetation and their flights are usually made low over openings between thicket patches.”

Voice: Mrs. Nice (1931) writes:

There is no music Ia the Bell Vireo’s refrain, but it possesses a quaint charm in its air of enthusiasm, in the rapid jumble of it all. It may be phrased whiflowhce, whillowhee, irked; sometimes there are three irkifloirkecs. Either song may end with a rising or falling inflection. When the bird is thoroughly in the mood, his rate is a song every 3 seconds, but this rapid pace is seldom kept up as long as a minute, 15, 16 and 17 songs a minute being the highest numbers I have recorded, while 8 or 12 are more commonly heard. As for hour records, a nesting bird sang the following number of times: 32, 56, 57, 61, 70, 99, 131 and 254. These birds seem to sing all day long and all summer long, although In August their zeal diminishes; the last songs are heard from the 13th to 21st of September.

Unlike most birds the male sings a great deal In the home bush; In the 9 hours of observation 388 songs were given there and 417 elsewhere. He even sings while sitting on the eggs. On June 22 during a 41 minute session of incubation, the absurd little bird gave 30 songs.

Elsewhere (1929) she noted, on September 6, 1925:

The Bell Vireo sings a little each morning. One day we saw him eating berries of black alder, in the meantime singing his regular jiggledy jiggledy ice; he also had a scolding kind of song: zip zip zip zip zip zip gee. Sometimes this was preliminary to the ordinary song, sometimes not. * * * The scold, chce ekee ekee ckce, is the most expressive utterances, given by both male and female. A sputtering spec spec, heard from the male during nest building, appeared to be a courting note. The juvenile call note is a single nasal pink. A cuckoo-like kuk kuk kuk kuk kuic was heard August 12, and a loud unk on July 10; the significance of these notes is unknown.

Mr. Du Bois (1940) writes: “The principal song of the first male was a rather long continuous sentence, usually declarative, ending quite emphatically, but sometimes ending with a rising infl~tion as though asking a question. The form was somewhat on the order of a warble, but the effect was never very musical. The same bird had an entirely different song, with loud harsh squeaks as a prominent element: a performance difficult to describe, and certainly unique in bird music.”

Mr. Skinner (1925) gives somewhat similar renderings of the song, and mentions a “call, a harsh scolding, though not so harsh as similar calls of the White-eyed Vireo; uttered as bird moves about tree and bush in search of food. In presence of intruder, a short, exceedingly quick, scolding too-weea-skee or ter-weea-wee.”

Pitelka and Koestner (1942) says: “On July 2, Koestner recorded an exchange of place on the nest when, as the male left, the female approached and sang twice. The occurrence of female song in this species was not ascertained further (although suggestive evidence had been recorded on June 22 and 26).”

Field marks: Bell’s vireo has no very conspicuous field marks; it is a plainly colored little bird in merging shades of gray and olive; it has a rather inconspicuous whitish eye ring and one or two whitish wing bars; and its sides and breast are faintly washed with yellowish. It is mostly to be seen in the haunts of the white-eyed vireo, which has a very conspicuous white iris, or in thickets with the black-capped vlreo, which shows a decided black cap.

It is smaller than the other vireos, and its song is distinctive.

Enemies: As it builds its nest so near th~ ground, its young are easy victims for the cat. Undoubtedly cats and cowbirds are its worst enemies. Mrs. Nice (1931) reports that of 17 nests found in Cleveland County, OkIa.., 15 were failures, 4 due to cowbirds and at least 3 to cats. Elsewhere (1929) she says that out of nine failures, seven were due to cowbirds; but in no case was a cowbird raised. The first three attempts at nesting studied by Pitelka and Koestner (1942) were failures, probably due to interference by cowbirds. Dr. Friedmann (1929) says that Bell’s virco is a common victim of two races of cowbirds; he has dozens of records in his files. Roy Quillin wrote to him that the vireo “will sometimes build another layer, or, rather, add a layer of lining, and cover up the eggs of the cowbird. They must often push the foreign eggs from the nest, as I have seen many, many eggs of the cowbird on the ground under a nest of this species. Yet the Bell’s vireo will hatch the eggs in the majority of cases.”

Other observers evidently do not quite agree with Mr. Quillin in his last statement. The evidence seems to indicate that the vireo will usually desert the nest, if imposed upon by a cowbird. George A. Moore (1928) writes from Stiliwater, Okia.:

We found ten nests, all constructed in the same manner and of much the same material. All were located within one hundred yards of the first one found. One nest had a Cowbird egg only; one had a vlreo egg and a Cowbird egg; one had a vireo egg; another had two dead vireos (young) and one vireo egg that had not hatched; the others were empty. From all appearances the nests were all built that season. One nest was so high in a slender bush that we could not see Into IL The incident suggests to me the possibility that Bell’s Vireo leaves its nest when bothered by the Cowbird, moves over to a new site and builds a new nest. There were only the two vireos In the ravine.

Harold M. Holland writes to me from Galesburg, Ill.: “Cowbirds are responsible for the abandoning of many nests, and I rather believe that the Bell’s contribution toward increasing our cowbird population may be considered relatively small.”

Pitelka and Koestner (1942) write: “Both incubating adults and young apparently suffer infestation by the northern fowl mite, Liponis~w~ aylviarum (Can. & Franz.). On July 2, the adult bird on nest No. 4 pecked and scratched its breast while on the nest. The mites were numerous on the following day when the young hatched. A heavier infestation was recorded at the nest of pair B, containing three young on July 11; on July 14, two young left the nest and a third was found dead in the nest. On July 15, the rim of this nest and adjoining twigs were covered with ‘thousands’ of mites which dropped to the ground in a continual little shower.”

Range: Western United States south to El Salvador.

DISTRIBUTION

Breeding range: Bell’s Vireo breeds north to north central and southeastern California (Red Bluff and the Mount Lassen region, Owens Valley, and Death Valley) ; southern Nevada (Ash Meadows); central Arizona (Fort Mojave, Fort Verde, Salt River Wildlife Refuge, and the Graham Mountains); specimens have been collected in April at St. George, southwestern Utah; southern New Mexico (Gila River and San Antonio); extreme eastern Colorado (Holly, Wray, and Julesburg) ; has been reported from Wyoming (Freezeout Mountains); central northern Nebraska (Thedford and Valentine) ; southeastern South Dakota (Yankton, Sioux Falls, and Dell Rapids); southern Minnesota, casually (Minneapolis and Winona); southern Wisconsin (La Crosse and Madison); and northeastern Illinois (Chicago). East to eastern Illinois (Chicago, Urbana, and Fox Prairie); western Tennessee (Memphis, one record); east-central Arkansas (Stuttgart); eastern Texas (Marshall, Houston, CorpusChristi, and Point Isabel); and central Mexico (Jacala, Hidalgo). South to central Mexico (Jacala) ; central Durango (Rio Nazas); central Sonora (Ures); and northern Lower California (San Fernando). ~Vest to western Lower California(San Fernando and San Telmo) ; and southwestern and central California (San Diego, Santa Barbara, Sargent, Sacramento, Marysville, and Red Bluff).

Winter range: The winter range of the races of the Bell’s vireo is discontinuous, but present information is inadequate to assign the range of each race. The species occurs in winter in the Cape region of Lower California as far north as Santa Margarita Island; in the tropical region of southern Sonora as far north as Ures and probably in northern Sinaloa. It is found from southern Guerrero (Coguca and Chilpancingo) through Oaxaca (Chivela and Tehuantepec) to Guatemala (Ocos, Sacapulas, and Gualam); and in El Salvador (Barra de Santiago and Divisadero). The species has been reported to reach northern Nicaragua, but no records of specimens are at present available.

The range as outlined includes the entire species, which has been divided into four subspecies or geographic races. Bell’s vireo, the typical race (V. b. belli), breeds from Colorado to Illinois south through eastern Texas to Tamaulipas; the Texas vireo (V. b. medius) breeds from southwestern Texas to central Mexico; t.he Arizona vireo (V. b. arizonae) breeds from southeastern California to southwestern New Mexico south to Sonora and Chihauhua; the least vireo (V. b. pusillus) breeds in central and southwestern California south to about latitude 300 in Lower California.

Migrations: Early dates of spring arrival are: Texas: Austin, March 26. Oklahoma: Tulsa, April 15. Missouri: Concordia, April 13. Illinois: Quincy, April 18. Iowa: Ames, April 30. Kansas: Manhattan, April 22. Nebraska: Stapleton, April 24. South Dakota: Dell Rapids, April 24. Arizona: Tucson, March 21. California: Santa Barbara, March 7.

Late dates of fall departure are: California: Azusa, October 3. Arizona: Tombstone, October 20. Colorado: Fort Morgan, October 6. New Mexico: Chloride, September 20. South Dakota: September 5. Nebraska: Red Cloud, October 1. Kansas: Onaga, September 27. lowa: Grinnell, September 12. Missouri: Columbia, October 3. Oklahoma: Oklahoma City, October 18. Texas: Cove, October 15.

Casual records: A specimen was collected in Durham, N. II., on November 19, 1897; a specimen has been recorded as taken at Detroit, Mich., on May 26, 1885, but the original label has been lost and the correctness of the locality has been questioned; a specimen in fall migration was collected on Deer Island, Miss., September 18, 1939.

Egg dates: Arizona: 35 records, April 24 to July 1; 18 records, April29 to May 29, indicating the height of the season. California: 105 records, April 7 to June 27; 58 records, May 11 to June 10. Illinois: 18 records, May 25 to July 6; 11 records, May 25 to June 5. Kansas: 26 records, May 20 to July 1; 15 records, June 7 to 16. Texas: 47 records, April 25 to July 1; 24 records, May 13 to 29.

TEXAS VIREO

VIREO BELLI MEDIUS Oberholser

HABITS

In southwestern Texas, Presidio, Brewster, and Kinney Counties, and farther south in Mexico, we may find this subspecies.

According to Ridgway (1904) it is “similar to V. 1. beliji, but coloration paler and tail averaging longer; pileum and hindneck brownish gray instead of grayish brown; olive of back, etc., grayer; under parts whiter, with olive-yellow of sides and flanks much paler; under tail-coverts and axillars white, yellowish white, or very pale sulphur yellow.”

Referring to Brewster County, Van Tyne and Sutton (1937) write:

The vociferous Texas Vireos were common In the thick tangles of mesquIte and willow along the desert draws and about springs and cattle ponds. Occasionally a few were found at a distance from surface water, but they were always much more numerous where water was available.

Since the male usually sIngs when an intruder approaches, a fairly accurate estimate of their abundance could be made. The Texas Vireo is unquestIonably one of the most common inhabitants of the mesquite thickets of the region.

On May 4, 1935, they located two nests in willow trees along the Rio Grande, “one with two slightly incubated eggs, and one newly made and ready for eggs. On May 11 we found a nest four feet from the ground with four young about five days old in a mesquite bush.”

The nesting and other habits seem to be similar to those of the species elsewhere. The measurements of nine eggs average 17.0 by

12.7 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 17.5 by 12.2 and 16.5 by 13.2 millimeters.

ARIZONA VIREO

VIREO BELLI ARIZONAE Ridgway

HABITS

This might be called the desert race of the species, found along the Colorado River in southeastern California, in southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, and from central western Texas southward into Chihuahua and Sinaloa.

Ridgway (1904) describes it as “similar to V. b. mediu8, but still paler and grayer, the back and scapulars brownish gray, like pileum and hindneck, the sides and flanks faintly washed with more grayish olive-yellow; tail and tarsus decidedly longer. Young with under parts pure white, the sides, flanks and under tail-coverts tinged with pale sulphur or primrose yellow; pileum and hindneck light pinkish gray, approaching &ru drab; back and scapulars vinaceous-drab.”

Dr. Joseph Grinnell (1914) met with the Arizona virco at all stations all t.he way down the Colorado River, it “being one of the most characteristic avifaunal elements in the riparian strip”. He says further:

The bird foraged in all of the component associations, but was perhaps best represented in the willow association, especially where there was an undergrowth of guaternote (Bacchari.s glutinoso).

On the Arizona side above Bill Williams River, March 14, I was able to make some observations on local distribution. Here the willow association was narrow but well defined, and the vireos were closely confined to it. A singing male occupied each segment of about 200 yards in this belt, just about the same spacing as the Lucy warbler in the adjacent mesquite belt. Each pair of vireos was closely delimited In the forage beat by that of its neighbor.

Each pair In Its own area actively resented encroachment by others of its own species. The vireos worked a rather low zone of foliage, from the ground up to a height of six or eight feet.

In Arizona, in 1922, we found this vireo only at the lower levels, in the valley of the San Pedro River, where it frequented the narrow strips of willows, small cottonwoods, and underbrush along the irrigation ditches, and in the extensive mesquite forest near Tucson. In the former locality the willow association was full of birds, roadrunners, Abert’s towhees, Sonora yellow warbiers, desert song sparrows, and Sonora redwings.

W. E. D. Scott (1888), however, found them “breeding throughout the region up to an altitude of 4000 feet. In the Catalinas they arrive about the 25th of March and by April are common. They are apparently mated on arrival, and at once proceed to build nests and lay eggs. Two broods are generally raised and three eggs are commonly found to form the brood. They leave the Catalinas early, by September 5, but are to be found on the plains about Tucson much later.”

Nesting: The only nest of the Arizona vireo that I collected was taken on May 27, 1922, near Fairbank, in the San Pedro Valley. It was suspended 8 feet from the ground between two twigs and close to the stem of a slender willow near one of the irrigation ditches. The nest, now before me, is a typical vireo basket, none too firmly attached to the two twigs and made of various vegetable fibers, conspicuous among them being split shreds of sacaton and Johnson grasses, which grew in profusion in the surrounding fields; mixed with these are strips of soft inner bark, finer grasses, bits of willow cotton, plant down, pappus, spider nests, etc., and considerable cattle hair, all firmly bound together; the lining consists of the very finest grass tops with a little cattle hair. It measures about 3 by 2½ inches in outside diameter and at least 2 inches in outside depth; internally it measures about 21/4 by 13/4 in diameter and about 1Y2 inches in depth. It contained four fresh eggs, two of the vireo and two of the dwarf cowbird.

A nest taken by Frank Stephens and sent to William Brewster (1882) was “pensile between the forks of a small mesquite branch about five feet from the ground, in a thicket of weeds and brush.” A nest found by Dr. Grinnell (1914) in the Colorado Valley “was attached to the forking stalk of a guatemote five feet above the ground. It would appear that many nests meet with disaster from their being built, as they so often are, in openings between thickets. These openings serve as passage ways for browsing cattle, which as they crowd through, force the supporting branches aside and demolish the nests. Evidence of a number of instances of this type of catastrophe came to notice. * * * A nest found April 24 on the Arizona side, five miles above Laguna, was located three and one-half feet above the ground on a horizontal willow branch, beneath and darkly shaded by several small willow trees growing close together at the margin of an overflow slough.”

Eggs: The set of eggs for the Arizona vireo seems to consist of either three or four, perhaps most commonly three. These numbers often include one or two eggs of the dwarf cowbird. The eggs of this subspecies are apparently indistinguishable from those of Bell’s vireos elsewhere. The four eggs taken by Dr. Grinnell (1914) were “dotted very sparsely about the large ends with bay and hazel.” The measurements of 30 eggs average 17.0 by 12.6 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 18.5 by 12.9, 17.2 by 13.2, 16.0 by 12.4, and 16.1 by 12.2 millimeters.

Enemies: This, like other races of Bell’s vireo, is a common victim of cowbirds.

LEAST VIREO

VIREO BELLI PUSILLUS Coues

HABITS

The name least vireo was appropriate when applied to all the vireos of this species in the far West and Southwest, as it formerly was; but it seems to be a misnomer for the California race, as its measurements indicate that it is slightly larger than either the Arizona or the Texas race.

Ridgway (1904) describes it as “similar to V. 6. arizoiwe, but still grayer above and whiter beneath; the upper parts between olive-gray and mouse gray without distinct tinge of greenish olive except on rump and uper tail-coverts (and there obviously only in fresh plumage); under parts nearly pure white, including under tail-coverts, the sides and flanks washed with pale olive-gray or grayish olive, but with only the merest trace of yellow tinge; wing and tail averaging longer. Young with upper parts decidedly paler and grayer, and under parts of body, with under tail-coverts, pure white throughout.”

The haunts of the least vireo in California are similar in a general way to those of Bell’s vireo in the Central States, mainly dense thickets of willows, and low bushes along streams or damp places, or in alder thickets in wet bottom lands. In the Lassen Peak region, according to Grinnell, Dixon, and Linsdale (1930), “it lived for the most part near the ground in the stream-side willow thickets. Individual birds were seen also to forage into grapevine tangles, valley oaks, and live oaks. * * * The closest avian associate of the least vireo was the yellow warbler. For example, a mid-river island in the Sacramento two miles or so above Red Bluff, and comprising about ten acres, harbored on May 7 three singing male vireos and eight singing male warbiers. But in foraging, the vireos kept near the ground, below about the 3-foot level, while the warblers kept mostly above that level.”

Nesting: Grinnell and Storer (1924) record a completed nest that they found in the Yosemite region on May 8, 1919:

It was in deep shade under a thicket of willows and white alders which grew on the lower slope of a pile of gravel left by a gold dredger. The nest was 19 Inches above the gravel, and Instead of being placed in one of the stout crotches of the adjacent alder It had been lashed to a slender fork on the brittle stem of a weed of the previous season’s growth. This was only 7 feet from the margin of a pool of quiet water. In form the nest was a well rounded, deep and rather thin-walled cup with slightly inrolled rim. It was composed of dry shreds of plants felted compactly with down from cottonwoods and willows. Outside, it measured 2 inches In height and 2’A inches in greatest diameter, while the interior was 1~ Inches deep at the center and about 1% inches across the opening.

In what was once called Nigger Slough, near Los Angeles, on May 30, 1914, we found a least vireo’s nest containing two eggs; it was hung in a fork of a slender willow sapling in a thicket of these trees, 7 feet above the damp ground; in construction, it was similar to the one mentioned above.

The nests often contain cowbirds’ eggs, as do all other races of this common host.

Eggs: The eggs are like those of the species elsewhere. The measurements of 40 eggs in the United States National Museum average 17.4 by 12.7 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 19.1 by 12.2, 18.0 by 13.2, and 15.8 by 11.2 millimeters.

Behavior: Grinnell, Dixon, and Linsdale (1930) watched a pair of these vireos on April 23, 1928, in what may or may not have been part of a courtship performance: “The birds were in willows and sparse brush along a small stream in the hills. One, probably the male, was singing and keeping within one meter of the other, both moving through the low branches, feeding. The singing bird kept its tail spread and frequently gave it a twitch, spreading the feathers still more. Also at intervals the tail was pushed downward to a nearly vertical position.”

James Murdock, of Glendale, Calif., writes to me: “An experience with a least vireo, concerning the stealth with which it sometimes approaches its nest, may interest you. A friend and I watched a pair of birds moving in and out of the willows in a stream bed near Santa Ana, Calif., and we soon felt that we had located the area in which the nest was placed. Time after time we would search this area and find nothing. Finally, in desperation, we decided to stand on the outskirts of this area, absolutely still (as nearly as we could manage it) and more or less hidden in the thick branches of the willoxvs. My friend did not succeed in standing very still, but regardless of his movements, we soon saw the bird enter the branches at the usual place. What was our surprise to see the bird turn sharply in flight just after it had entered the tree area and fly directly to a branch that was hanging down just over the head of my friend. Then the bird seemed to disappear. The mystery was solved only when we began to search every inch of this branch. Concealed from our view, directly above the spot on which my friend had been standing, was the tiny nest with the bird in it. We were able to touch the bird in the nest and she did not fly. We must have looked at it directly more than 15 times before it could be seen.”

Voice: Grinnell and Storer (1924) give two descriptions of the song of the least vireo, somewhat different from those given for the eastern Bell’s vireo: “To one observer the song sounded like this: we-cher, eke we, eke we-ekey? we eker, eke we, eke we, cheey. Each set of syllables was uttered rapidly, with a distinct rest between the two.” The other song was uttered by the male while he was following the feeding female. “This song was transcribed on the spot as wreteky, wreteky, wreteky, wreteky, wree? wreteky, wretchy wreteky, wretekeur, wreer. The r’s here indicate a burred or rolling quality; and the whole song was, as usual, hurried in its delivery. The questionand-answer inflection was striking.”

Field marks: The least vireo is decidedly smaller than the other California vireos, except Hutton’s, and slightly smaller than the latter. Hutton’s vireo is more stockily built, its plumage more fluffy, its movements more deliberate, and its white eye ring and two white wing bars are more conspicuous. The least vireo is slimmer in outline, it is very active in all its movements and its general coloring is grayish, rather than greenish; it lives in the low thicket, rather than in the trees, and its song is quite distinctive. One of its two whitish wing bars is often inconspicuous or worn away to obsolescence, so that it shows only one.