Unusual among gulls, the California Gull breeds on inland lakes rather than in coastal areas. Breeding colonies can number in the tens of thousands of birds. Winter, though, finds California Gulls having moved to the West Coast for a few months.

California Gulls occasionally reuse a nest from a previous year, and often incorporate bones or feathers of bird that died the year before. If they survive their first year, California Gulls are known to have lived as long as 30 years.

On this page

Description of the California Gull

BREEDING MALE

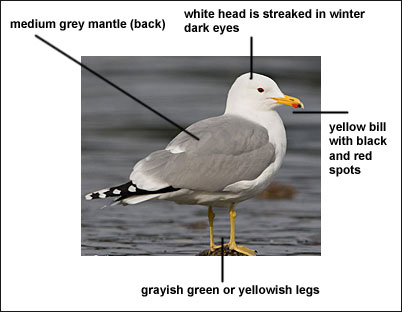

The California Gull is a medium gull with plumage that varies somewhat by age and by season. Breeding adults have white heads and a yellow bill with both black and red markings near the tip. A white foreneck neck and underparts contrast with gray upperparts. In flight, the primaries are extensively black with small white tips. Length: 21 in. Wingspan: 54 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Winter adults have brown streaking on the head and nape.

Juvenile

Immature birds are mostly brown, with a black-tipped pinkish bill. They attain adult plumage by age four.

Habitat

California Gulls inhabit coastal areas, lakes, farms, and towns.

Diet

California Gulls eat insects, fish, garbage, and eggs.

Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

Behavior

California Gulls forage by walking, wading, or swimming.

Range

California Gulls breed in western Canada and parts of the western U.S. They winter along the Pacific Coast. They can be seen in migration across much of the western U.S. The population is increasing.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the California Gull.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

The 1848 plague of grasshoppers affecting Mormons in Utah was alleviated when numerous California Gulls arrived and began consuming the insects.

California Gulls are typically found near saline lakes.

Vocalizations

The voice is often described as being high and scratchy

Similar Species

Herring Gull

Herring Gulls are larger, with paler backs.

Western Gull

Western Gulls have darker mantles (back).

The Ring-billed Gull is smaller, with a shorter bill lacking a red spot. Has paler mantle than California Gull, and the obvious black ring on the bill.

Nesting

The California Gull’s nest is a depression lined with weeds and grass. It is placed on an island or on land near water.

Number: Usually lay 2-3 eggs.

Color: brownish or olive with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 23-27 days, and leave the nest within a few days, though they cannot fly for about 45 days and they associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the California Gull

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the California Gull – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

LARUS CALIFORNICUS (Lawrence)

It has always seemed to me that the above name should have been applied to the western gull, Larus occidentalis, the characteristic gull of the California coast., for the subject of this sketch, Larus californicus, is essentially a bird of the inland plains. It is common enough on the California coast in winter, together with several other species, but it is not known to breed within that State except in the elevated regions east of the Sierras in the northern part of the State. Although we are accustomed to associate gulls with the seashore this species seems to be confined, during the breeding season, to the interior, where it is widely distributed and in many places abundant, particularly in the vicinity of the larger lakes, from northern Utah to the barren grounds on the Arctic coast. The exact limits of its distribution are none too well known, for the casual observer might easily mistake it for the herring gull, which it closely resembles. The ranges of the two species come together at the eastern edge of the Great Plains, and undoubtedly many mistaken identifications have been made where specimens have not been collected. Such was the case at Crane Lake, Saskatchewan, where the herring gull had been reported as breeding abundantly, but where all of the large gulls that we collected during two seasons’ work proved to be California gulls, which were very common.

Although there were at least 500 pairs of gulls nesting so close together, yet housekeeping was in no sense a communal matter. The nests were within 2 or 3 feet of each other, hut each pair of gulls had Its own home spot, and the Invasion of that place by any other gull was the challenge for a fight. Several times we were the excited spectators of fights that were going on just outside our tent. I watched one old hen, who was very angry because she could not find her chicks. As one of her neighbors lit near she grabbed the tail of the intruder and gave it a sharp jerk. At that both birds grasped each other by the bill and a lively set-to followed. They pulled and tugged till suddenly the old hen let go and grabbed her opponent by the neck and began shaking and hanging on with all the tenacity of a bull pup, till the intruder got enough and departed, leaving the victor with a mouthful of feathers.

Mr. Oliver Davie (1889) says of the nests of the California gull:

The nests of this species are made on the ground or built on rocks, and sometimes where the birds are breeding In vast colonies the nests are placed on stunted sage or greasewood bushes. They are built of sticks, grass, and a few feathers.

Eggs: As with most water birds, only one brood is raised in a season. The usual set consists of three eggs, but two are often considered sufficient; four eggs are laid occasionally, and five have been reported. The eggs are similar to other gulls’ eggs, but they are usually handsomer and often more boldly marked with striking colors. The shell is thin and lusterless. The shape varies from short ovate to elongate ovate. It is usually more pointed than in other gulls’ eggs, and is sometimes nearly ovate pyriform. The ground color shows a variety of shades from “Saccardo’s umber” or “buffy brown,” in the darker specimens, to “light drab,” “smoke gray,” or “olive buff,” in the lighter specimens, which are much commoner. The commonest types of eggs are spotted more or less evenly with rather small spots of irregular sizes and shapes, but many of them are boldly marked with large spots and blotches; often lighter and brighter shades of brown seem to be overlaid on spots of darker brown or gray, producing handsome effects. Some eggs are oddly decorated with fantastic scrawls and irregular lines, such as are seen on murres’ eggs. These markings are generally in the darker and richer shades of brown, such as “bone “olive brown,” “warm sepia,” and “Vandvke brown.” Nearly all eggs show underlying spots of “light violet gray,” or similar colors. The measurements of 50 eggs in the United States National Museum average 67.5 by 45.5 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 71.5 by 47.5. 69 by 50.5, 57.5 by 41. and 65.5 by 40.5 millimeters.

Young: I have no data on the period of incubation, which is probably about the same as with other large gulls. Probably both sexes incubate. The young are quite precocial; after a few days in the nest, they learn to run about and hide among the stones or under the vegetation near their nests. They are good swimmers and, even when very small, will take to the water readily and swim away until driven back by their parents, who keep a careful watch over them. Mr. Finley (1907) says of their behaviors at this time: I soon discovered that their greatest anxiety seemed to be to keep their children crouching low in the nest so they would not run away and get lost In the crowd. I saw one young gull start to run off through the reeds, but he hadn’t gone a yard before the mother dived at him with a blow that sent him rolling. He got up dazed and started off In a new direction, but she rapped him again on the head till he was glad to crouch down In the dry reeds.

The parents seemed to recognize their own chicks largely by location. Several times I saw old birds pounce upon youngsters that were running about and beat them unmercifully. It seemed to be as much the duty of a gull mother to beat her neighbor’s children If they didn’t stay home as to whip her own If they moved out of the nest, but often this would lead to a rough and tumble fight among the old birds. Sometimes a young gull would start to swim off In the water, but It never went far before It was pounced upon and driven back shoreward.

Plumages: The young bird, when first hatched, is covered with thick, soft down of plain, light colors to match its surroundings, “light buff” to “cartridge buff,” brightest on the head and breast; the upper parts and throat are clouded or variegated with light grayish, and the head is sparingly spotted with dull black. These colors fade out to a dirty grayish white as the bird grows older. The juvenal plumage is much like that of the herring gull; the head and underparts are dark and mottled, the dusky markings prevailing; the upper parts are boldly mottled, each feather being broadly edged with buffy white and centrally dusky. The first winter plumage, which is acquired early in the fall by a partial molt of the body feathers, is everywhere mottled with dusky, the underparts, especially the neck and breast, being tinged with cinnamon; the tail, which in the young ring-billed gull is basally gray, and the primaries are uniform brownish black and the bill is dark. This plumage is worn for nearly a year or until the first postnuptial molt, when the bird is a year old. This molt is complete, producing the second winter plumage, which is more or less mottled with dusky, except on the mantle, which now becomes more or less clear “gull gray.” The new primaries are nearly black, but with little or no white tips; the tail is white at the base, becoming dusky near the tip. The bill becomes yellow at the base, but the outer half remains dusky. A partial prenuptial molt occurs during the latter part of the winter or early spring in both old and young birds, producing whiter heads and necks.

A nearly adult winter plumage is acquired at the second postnuptial molt, when the bird is a little over 2 years old. At this molt, which is complete, the black primaries with limited white tips and the pure white tail, often subterminally marked with dusky, are acquired; the bill becomes wholly yellow. Winter adults have elongated dusky markings on the crown and a necklace of dusky spots on the hind neck, which are lost at the partial prenuptial molt before the next breeding season. The bright chrome yellow of the upper mandible and the vennilion of the lower mandible are characteristic of the breeding season. Subsequent seasonal molts of the adult are merely repetitions of the complete postnuptial in the summer and the partial prenuptial molt in early spring, involving only the head and neck.

Food: The feeding habits of the California gull make it one of the most useful of birds to the agriculturist of the western plains, where it makes its summer home. Rev. S. H. Goodwin (1904) says of its habits in Utah:

I have watched them for hours as they circled about the newly plowed field, or followed close behind the plowman, as blackbirds do in some localities, or sunned themselves on the ridges of the furrows after a hearty meal of worms. I have studied them as they fared up and down the river in search of dead fish and other garbage, or assembled in countless numbers in some retired, quiet slough where they rent the air with their harsh, discordant cries and demoniac laughter, or sailed on graceful wing in rising circles till lost In the deep blue of heaven.

Mr. Dutcher (1905) publishes the following interesting letter from Mr. John E. Cox, of the Utah Board of Agriculture:

Gulls go all over the State for insects, the greatest number visiting the beet fields, where they keep down the crickets, grasshoppers, cutworms, etc. They took a new diet this summer. Some alfalfa fields were so badly honeycombed with mice holes and runs that it was Impossible to irrigate them, and they were plowed up, mostly for beet culture. When the water was turned into the irrigation ditches the mice were forced out of their holes, and the gulls then caught them. They became so perfect in their work that they kept abreast of the head of the water and picked up every mouse that appeared. When gorged with victims they would vomit them up in piles on the ditch bank and recommence their feeding. Gulls are sacred in Utah, and are so tame that oftentimes they may he caught by band as they follow the plow so closely.

Dr. A. K. Fisher (1893) reports that a specimen of this species, shot at Owens Lake, California, “on December 28, had its craw full of duck meat and feathers, and from the actions of its associates when a duck was shot it was evident that they prey upon such game, since the lake affords little other food.” During the two seasons that I spent in Saskatchewan we saw the California and ring-billed gulls almost daily visiting the garbage heaps on the outskirts of Maple Creek, where they found a good supply of food to vary their natural diet of insects and other animal food picked up on the prairies and about the lakes. During their winter sojourn on the Pacific coast they follow the example of others of their kind and become largely scavengers about the harbors. They also, probably, feed on fish to some extent.

Behavior: Mr. Finley (1907) refers to their powers of flight as follows:

These gulls are masters in the air. I have watched by the hour birds similar to these following along in the wake of a steamer, but had never before bad such chances with a camera. Often they poise, resting apparently motionless on outstretched wings. It is a difficult feat. A small bird can not do it. A sparrow hawk can only poise by the rapid beating of his wings. The gull seems to hang perfectly still; yet there Is never an instant when the wings and tail are not constantly adjusted to meet the different air currents; just as is shooting the rapids in a canoe the paddle must be adjusted every moment to meet the different eddies, currents, and whirlpools, and it is never the same in two different instants. A gull by the perfect adjustment of its body, without a single flap of the wings, makes headway straight In the teeth of the wind. I saw one retain a perfect equilibrium in a stiff breeze and at the same time reach forward and scratch his ear.

Mr. Dawson (1909) pays the following tribute to their prowess on the wing:

Graceful, effortless, untiring, but above all mysterious, is that power of propulsion by which the bird moves forward into the teeth of the gale; indeed, is advanced all the more certainly and freely when the wind is strong. From the deck of a steamer making 15 miles an hour against a 15-knot breeze, I once stretched my hand toward a soaring gull. He lay suspended in mid-air without the flutter of a feather, while the air rushed past him at the rate of 30 miles an hour; and he maintained the same relative position to my hand, at 5 or 6 feet, for about a minute. when he tired of the game, he shot forward. And again, there was not in the motion the slightest perceptible effort of propulsion, hut only a slightly sharper inclination of the body and wings downward. We see clearly how it must be, yet we can not understand it. The gull is a kite and gravity the string. The bird is a continually falling body, and the wind is continually preventing the catastrophe. Yes, we see it – but then, gravity isn’t a string, you know; and so why doesn’t the wind take the kite along with it? Well, there you are; and not even Hamilton, who discovered quaternions, could have given the mathematics of it.

My knowledge of the vocal powers of the California gull is confined to what I heard and noted on its breeding grounds, where its vocabulary was limited. The ordinary cry was a soft, low “kow, kow, kow,” or “kuk, kuk, kuk,” much like the notes of other gulls. When the birds became much excited or alarmed they indulged in shrill, sharp, piercing cries. Gulls are usually silent birds, but while feeding, quarreling, or showing active emotions, they have a variety of notes to express their feelings or to communicate their ideas to their fellows, all of which seem to be understood.

California gulls seems to be quiet, gentle, harmless birds, and I have no evidence to show that they do any appreciable damage to the various species with which they are associated on their breeding grounds, though they do occasionally steal a few eggs from unprotected nests. They have been found nesting in colonies with ring-billed gulls, Caspian terns, white pelicans, double-crested cormorants, and great blue herons. So far as I know they have no formidable enemies among birds and are not much molested by man. They select for their breeding grounds islands in remote lakes far from the haunts of man, where they are probably safe until the encroachments of civilization drive them out. They are not suspicious or wild; in fact, they are much tamer than most gulls, but they do not seem to be fond of human society.

Winter: The fall migration is westward to the Pacific coast or southwestward to the large inland lakes of the Southwestern States and Mexico, where they spend the winter, associating on the coast with various other species of gulls.

DISTRIBUTION

Breeding range: Western North America. East to Great Slave Lake and northeastern North Dakota (Stump and Devils Lake). South to northwestern Wyoming (Yellowstone Lake), northern Utah (Great Salt Lake), western Nevada (Pyramid Lake), and northeastern California (Eagle Lake). West to central southern Oregon (Klamath Lakes) and central British Columbia. North to northern Mackenzie (Anderson River region). Occurs in summer from Washington (Bellingham Bay) to southeastern Alaska (Ketchikan), but not known to breed there.

Breeding grounds protected in the following national reservations: In California, Clear Lake; in Nevada, Anaho Island (Pyramid Lake); in Oregon, Klamath and Malheur Lakes; in Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park.

Winter range: Pacific coast, from southern British Columbia southward to southwestern Mexico (San Mateo), and from northern Utah (Great Salt Lake) southward to the Gulf of California; rarely east to the coast of Texas.

Spring migration: Northeastward to the interior. Early dates of arrival: North Dakota, Devils Lake, April 24; British Columbia, Okanagan Lake, April 11. Late dates of departure: Lower California, San J05~ del Cabo, May 17; California, Monterey, May 19.

Fall migration: Southwestward toward the coast. Early dates of arrival: British Columbia, Chilliwack, August 26; Washington, Seattle, August 31; Oregon, Netarts Bay, September 8; California, Monterey, August 21 to October 9; Lower California, Magdalena Bay, November 24. Late dates of departure: Mackenzie, Hay River, November 5; Kansas, Reno County, October 20.

Casual records: It has been recorded in the Hawaiian Islands (Bryan) and in Japan (Seebohm):

Egg dates: Utah and Nevada: Fifty-six records, May 8 to June 26; twenty-eight records, May 13 to 20. North Dakota and Saskatchewan: Twelve records, June 4 to 22. California: Six records, May 18 to 25.