Baird’s Sparrows migrate through the Great Plains, but as a nocturnal migrant and a somewhat secretive grassland sparrow, they are seldom seen in migration. In fact, most records of Baird’s Sparrows from Kansas are of birds killed by collisions with television towers rather than of live birds seen in grasslands.

The Baird’s Sparrow and its other close sparrow relatives are more likely to run away through the dense grass of their prairie habitat than to fly if they are disturbed. This makes them very difficult to locate if they are not singing.

On this page

Description of the Baird’s Sparrow

BREEDING MALE

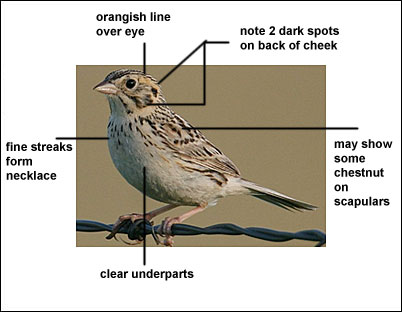

The Baird’s Sparrow has a dark back, heavily marked with buff, a pale, buffy-orange supercilium, a buffy nape with fine streaking, a breast band of dark streaks, and pale underparts.

Female

Sexes similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

Photograph © Greg Lavaty.

None.

Juvenile

Juveniles are quite similar to adults.

Habitat

Baird’s Sparrows inhabit northern prairies with native grasses.

Diet

Baird’s Sparrows eat insects and seeds.

Behavior

Baird’s Sparrows forage on the ground.

Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Range

Baird’s Sparrows breed in the north-central U.S. and south-central Canada. They winter in the southwestern U.S. and in Mexico. The population has declined in recent decades.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Baird’s Sparrow.

Fun Facts

Baird’s Sparrows are secretive and seldom seen during migration.

John James Audubon named the species in 1843, but its secretive habits meant that it would be decades before it was seen again. Today, it is declining because of continued loss of native grasslands

Vocalizations

The song consists of a series of high, jingling notes. A high “seep” call is also given.

Similar Species

Cassin’s Sparrow

Winter range of Cassin’s Sparrows overlaps with Bairds. Cassin’s has less streaking on the breast.

Clay-colored Sparrow

Clay-colored Sparrows have stronger face markings, with gray check, and pale streaks above and below the cheek mark.

Grasshopper Sparrow

Grasshopper Sparrows have buffy breast, very flat head and short tail.

Nesting

The Baird’s Sparrow’s nest is a cup of grasses, and is lined with finer materials. It is placed on the ground, well hidden in vegetation.

Number: 4-5.

Color: Whitish in color with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 11-12 days, and fledge at about 8-10 days, though remaining dependent on the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Baird’s Sparrow

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Baird’s Sparrow – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

AMMODRAMUS BAIRDlI (Audubon)

Contributed by JOHN LANE

On June 4, 1840, a 17-year-old youngster named Spencer Fullerton Baird overcame his boyish diffidence and wrote the great naturalist, John James Audubon, to inquire about a strange flycatcher he had collected. When the bird proved to be a new species (the yellow bellied flycatcher, Empidonax flazriventris), Audubon, then 60, was so impressed by the ability of his new acquaintance that a firm April: November friendship developed. This episode marked the first faint glimmering of what Coues (1903) called the “Bairdian Epoch.”

Three years later, on July 21, 1843, John G. Bell, a member of Audubon’s western exploring party, shot a male and female of a strange sparrow near the junction of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. When Audubon (1844) described it, he named the species “Baird’s bunting” (Emberiza bairdii), in honor of his young friend.

In her biography of her illustrious grandfather, Maria R. Audubon (1897) includes a footnote by Elliott Coues which states: “Special interest attaches to this case; for the bird was not only the first one ever dedicated to Baird, but the last one named, described, and figured by Audubon; and the plate of it completes the series of exactly 500 plates which the octavo edition of the ‘Birds of America’ contains.”

The strange history of Baird’s sparrow for the 30 years following its discovery is admirably traced in a monograph by three Winnipeg, Manitoba, field naturalists, Bertram W. Cartwright, Terence M. Shortt, and Robert D. Harris (1937). Their authoritative study of the species is quoted often in this history, beginning with the account of the rediscovery of Baird’s bunting:

Twenty-nine years clapsed before the species was again encountered by ornithologists and when it was re-discovered by Aiken, 11 miles east of Fontaine, El Paso Co., Col., on October 9, 1872, he thought he had a new species. Ridgway shared his views and named the bird Centronyx ochrocephalus, the type specimen being No. 162696 in tbe United States National Museum. It was later shown that the difference between Audubon’s Emberiza bairdii and Ridgeway’s Centronyx ochrorephcslus was due to seasonal plumage changes. The following year Coues found them breeding abondantly in North Dakota, collected about 75 specimens, secured young birds and made many field observations. Coucs supplied the principal museums with specimens f or the first time and in the fall of that year, 1873, Henshaw encountered them in great abundance in Arizona and also secured many specimens. We see, then, that following a hiatus of nearly thirty years, in one year: October, 1872, to October, 1873: the breeding range, migration routes, winter quarters, nest and eggs, plumage changes and juvenal plumage were all more or less established.

The above account gives no actual data on the nest and eggs of the species, and credit for the first nesting record goes to Joel Asaph Allen (1874), who found a nest with four eggs at Big Muddy Creek, N. Dak., July 1,1873.

During its 29-year hiatus, A. bairdii may have been out of sight, but it was certainly not out of mind, for at one time or other during that period, ornithologists gave the bird four different generic or subgeneric names. From Emberiza the name was changed to Cot urrnculus in 1850, to Centronyx in 1858, and to its present name, Ammodramus, in 1872. The British naturalist Sharpe referred to it as Pa,sserculus in 1888. In 1903 Coues gave the species two vernacular names: “grass sparrow” and “Baird’s savannah sparrow.”

Significant changes have occurred in the ecology of Baird’s sparrow since Elliott Coues (1878) found it in such numbers on the Dakotan prairies in 1873 that “In some particular spots it outnumbered all the other birds together.” This plenitude is now but a memory, and the Encyclopedia Americana gives the prime reason: “Few states in the Union have a larger percentage of tillable land than has North Dakota. * * * there are but small areas that are not marvelously fertile.” During the 1880’s settlers poured into the state, and with the turning of the sod, the species was doomed to severe decimation.

During the following 40 years this decline in numbers continued until Norman A. Wood (1923) reported: “On June 4, 1921, Mr. Elmer Judd and I made a long trip by automobile north from Cando [N. Dak.I to Snyder, Rock, and other small lakes. We were in quest of this species, but it was not until passing many of their old haunts that we at last found a male singing by the roadside near St. Johns [N. Dak.]. From here we drove north to the United States boundary line, and there saw our second bird. These were the only two specimens seen by me in life.”

For more recent word, Stanley Saugstad of the Minot, N. Dak., district, writes me in 1962: “I have never known Baird’s sparrow to be common in this area. There is very little native sod in my home community. I feel the species is less common than it was 15 or 20 years ago.” A letter from Mrs. Robert Gammell of Kenmare, N. Dak., adds: “In our area the birds are confined almost entirely to native prairie and are common in that habitat in the Des Lacs and Lostwood National Wildlife Refuges.”

Curiously enough, as the population of Baird’s sparrow declined in North Dakota, no general exodus seems to have taken place, either to adjoining states or to the prairie provinces to the north. Regarding this, Gale W. Monson of Arizona writes: “There is no question in my mind that the conversion of vast prairie areas to farmland had a profound effect on the numbers of Baird’s sparrows in North Dakota. This accounts, in my opinion, for the decline in numbers of this species found wintering in Arizona after 1880.”

With the elimination of North Dakota as an important breeding area, it is necessary to go north of the international boundary to find the greatest density of summering bairciji, since, at best, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Montana are but fringe areas for this species. Both Alberta and Manitoba have fair numbers of the bird, and more than half the known nests have been found in these two provinces. Here, in southwestern Manitoba, I always know of communities close by, but distribution is very spotty, as it is in all parts of the province where Baird’s sparrow summers.

Saskatchewan has been left till last purposely, as there is now strong evidence that the huge areas of suitable habitat in this province probably support a larger population of this species today than any other territory. Three veteran field naturalists, J. Dewey Soper of Alberta, and C. Stuart Houston and Manley Calm of Saskatchewan, have between them furnished me with a list of over 150 areas in this province where they have found Baird’s sparrow.

Manley Callin writes me: “My own observations lead me to believe that Baird’s sparrow is not nearly so restricted in distribution in Saskatchewan as has been indicated. I am inclined to speculate that almost every organized municipality (there are 296 of these) contains some suitable habitat, and that in any specified year, at least half of these and possibly a much higher number are hosts to Baird’s sparrows, ranging from a few to a considerable number.”

There remains one other ecological change to discuss: Cartwright et al. (1937) thought this was one of the species that would not conform to changing conditions, that it was one of the irrecondilables, but W. Earl Godfrey (1953) gives wheat fields as the habitat of Baird’s sparrow at Swan River, Manitoba, in 1937. Angus H. Shortt of Winnipeg, a member of the field party that gathered these data, writes me: “It was a very dry summer in the Swan River valley, and the wheat fields in question were extremely poor, thin, and with growth not over a foot in height. I was quite surprised to find the sparrows in this type of habitat, but they definitely seemed established. There was an adjoining area of upland grass similar to the territory occupied by this species at Deer Lodge, Manitoba, but for some reason the birds preferred the wheat field.”

A letter from Manley Callin mentions that he noted several males singing from a wheat field near Moosomin, Saskatchewan, July 16, 1945. More recently, Margaret Belcher (1961) states that “their breeding habitat in the Regina plains is apparently not restricted to native prairie grasslands. * * * on July 31, 1960, driving through farmlands north of Rowatt [Saskatchewanj we heard Baird’s sparrows singing in weedy grainfields on either side of the road. At least six separate songs were heard, presumably from birds in separate territories.” In none of these instances were nests located, and Baird’s sparrow seldom nests in such terrain unless there is also a great tangle of growth present at ground level.

In July 1965 I found a nest in a field that had been plowed and sown to brome grass (Bromus imermus) about 10 years earlier. Because the soil was light and sandy, the annual crop of brome gradually thinned out, and the field had not been harvested for several years. This allowed a ground cover similar to native prairie growth to develop, and the hen Baird’s sparrow made an excellent job of hiding her nest in it.

Spring: When spring comes to the midwest grasslands and the warming world awakes to the joyous minstrelsy of the swarms of newly returned prairie birds, aerial displays usually form an important part of courtship activities. Male prairie horned larks, chestnutcollared longspurs, western meadowlarks, bobolinks, and Sprague’s pipits all advertise their presence with ecstatic song flights. These aerial rhapsodies begin almost as soon as the birds reach the breeding grounds, and usually last until the nestlings need feeding. But no such courting flights aid those who seek the ground-dwelling sparrows. They who set out, in early May, to learn whether or not Baird’s sparrow has returned do not look for the little bird: they listen for him. He may not be there that day, or the next day either, and if any significant change has taken place in his habitat, he will not be there that May, or that year.

This is a neat little bird, with a prim little bib of radial lines on its upper breast, buffy patches on its cheek and neck, and an ochraceous stripe running through its crown. But identification is difficult, for none of these marks is clearly definable at any distance.

Though a few winter in the grasslands of Arizona and New Mexico, and in the counties of El Paso and Midland, Tex., most of these little finches start their spring migration from the Mexican states of Sonora (northern), Durango, and Coahuila.

The northward movement begins in late February and lasts a little more than 2 months. Mrs. Harold Williams of Midland, Tex., writes me that the birds may leave El Paso and Midland counties any time from April 9 to April 28. Richard R. and J. Graber (1954) took a specimen in Oklahoma on Apr. 23, 1953. William Youngworth writes from Sioux City, Iowa, that Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota are all in the migration path, and sends me Harold Turner’s dates for Nebraska as follows: “Arrival, May 4, 1952; May 3,1953; April 15, 1958; April 12, 1959; I\’Iay 5,1960; April 14, 1962.” These dates show that the leading front of the migration wave may vary from year to year by almost a month.

Few Baird’s sparrows are detected in migration because they are so inconspicuous. As with many other species of grass-inhabiting sparrows, they seldom travel in flocks, but usually in small groups, or even as single individuals, and arrive at their summer home without fanfare, unheralded, and often unnoticed. Mrs. Robert Gaminell of Kenmare, N. Dak., writes me: “Birds just appear on the breeding grounds.”

A letter from Clifford V. Davis of Bozeinan, Mont., gives late April or early May as the average arrival time for that state. Orin Stevens writes from Fargo, N. Dak., that data Perna M. Stine kept from 1929 to 1944 show the average return date for the Minot, N. Dak., area to be May 10.

For the Regina, Saskatchewan, district, Belcher (1961) states: “Usual spring arrival, second week in May; earliest arrival, May 10 (Lahrman).” Cartwright et al. (1937) include a table that shows an average spring arrival date in Manitoba of May 11 and for Alberta, May 10. Stuart Criddle reports the earliest arrival for Manitoba as Apr. 21, 1942. The only other April date for Canada is shown in the Cartwright et al. (1937) table: Apr. 28, 1922, at Belmont, Manitoba, as reported by J. C. Wilson.

Territory: Tbe males arrive first on the summering grounds and immediately establish their territories. I have watched these early arrivals as they disputed possession of a certain breeding area. Rival males leap up from the concealing grass like jack-in-the-boxes, face to face, wings pumping rapidly and claws raking wildly. In a moment they drop back to ground cover again, rest a few seconds, and leap into view once more. Finally one bird flees, the other pursues it a short distance and returns to his domain. Neither bird utters a sound during these contests.

Such struggles persist only for a few days, and soon each male is undisputed master of a sizeable piece of real estate, usually between 1 and 2 acres in extent. With the division of property settled, each male’s next action is to select several strategic singing perches within it. These may include a tuft of grass or weeds, a low bush, a post, a strand of fence wire, a boulder, and often he will sing from the ground. But from wherever he sings, the first time he throws hack his head and tinkles his silvery little bell-song, he discards the cloak of anonymity that has concealed his identity since he fell silent the previous fall.

Courtship: Cartwright et al. (1937) make the following observations on the courting activities of Baird’s sparrow:

One of us (T.M.S.) witnessed the real mating performance * * * on June 3, 1930. A male was observed acting strangely on a patch of matted straw. It was walking slowly along with head drawn in and tail slightly fanned; it vibrated first one and then the other wing rapidly over its back, resembling greatly the wing flutterings of a young bird about to be fed. lit never vibrated both wings at once. It bobbed its head to near the ground several times but made no sound during the performance. When it flew its wingbeats were abnormally fast and fluttering. It hardly seemed able to contain itself and had no sooner alighted on another patch before it recommenced the display.

Further examples of courtship performances xvere observed by one of us (R.H.D.) on June 27, 1931. Two singing males, whose territories adjoined, were frequently observed to invade each other’s territory. A tussle then ensued and the invader was then driven back to its own domain. They would sometimes pursue each other about erratically, often alighting, and sometimes fighting. The bird occupying the territory to the north of the other was found to be uttering a curious, soft, complaining whine, “Meeerr, meeerr, meeerr, meeerr, meeerr,” and so on. It was uttered either when the bird was on a bush, on the ground, or in low flight over the ground. The note was usually accompanied by wing flutterings when the bird was settled and by abnormally fast wing beats when in flight. Neither of these birds was seen on June 20. After three hours’ watching on June 27, a female was seen. Pursued by both males, she flew from the territory of the southern male to that of the northern male. Near the boundary of the two she dropped into the grass, followed by both males. The southern male now returned to his own territory, however, while the other one followed the female as she flew into a patch of mixed wolfberry and silver willow. The female could not be found there. She was seen sometime later, however, again near the boundary of the two territories. Both males came to her and fought for a brief time and then dispersed.

Nesting: Between 1873 and 1930 no more than 21 authenticated nests of this species were reported, 2 each from Minnesota and Montana, the rest from North Dakota and Alberta. Another nest was found in Alberta in 1931, and between 1930 and 1934 Cartwright, Shortt, and Harris (1937) found 15 nests in Manitoba. All but one of these were in two communities of Baird’s sparrows that had settled near the city of Winnipeg, perhaps in 1928. No major changes took place in these habitats during that time, and the birds returned each year to at least one of the areas.

Environmental disturbances caused by plowing, burning, brushing, or mowing and raking always result in Baird’s sparrow quietly abandoning an area. Nor can it prosper on close-cropped pastureland, and the introduction of grazing animals into a field usually causes the species to desert it. Mrs. Robert Gammell writes me from Kenmare, N. Dak.: “One of our favorite chestnut-collared longspur spots for many years was an over-grazed pasture, an area of about 160 acres west of Kenmare. In 1960 there were no cattle in the field and the grass grew up. Immediately a number of Sprague’s pipits and Baird’s sparrows joined the longspurs there.”

The impression still lingers that these sparrows prefer to nest in damp areas. Audubon (1844) found them hiding in the long grass of wetlands, and Taverner (1919) believed the absence of the species at Shoal Lake, Manitoba, in 1918: 19, was due to “the lowering of the lake level and the disappearance of the broad marshes.” The opposite view is expressed by Gale Monson, who writes me: “My impression, based on my experiences in both North Dakota and Arizona, is that the density of bairdii varies markedly from year to year on both the breeding and wintering grounds. In the damper parts of its breeding range, it is probably more plentiful in dry years, while in the drier parts of the range it is more numerous in wet years.”

Monson’s findings are supported by W. Ray Salt and A. L. Wilk (1958): “Grassy slough bottoms and alkali flats are favorite haunts in dry years but after a rainy cycle such places become too damp for Baird’s sparrow and the species may disappear from a locality which it has occupied for several years.”

My observations in Manitoba suggest that Baird’s sparrow likes to keep its feet dry and thus prefers well-drained terrain. A field of tangled grass, both old and new growth, mixed with various species of native plants, and with patches of western snowberry, wolfwillow, rose, or low willow perhaps present in the area, is a favorite habitat. This terrain may be close to wetlands, or it may be quite a long way from them. The main concentration near my own city of Brandon, Manitoba, is more than 2 miles from the river, the nearest water.

In selecting her nest site, the female Baird’s sparrow prefers longer grass than do some of her neighbors, such as the prairie horned lark, the chestnut-collared longspur, and sometimes the Sprague’s pipit. For her home she chooses a tangle of grass interspersed with prairie plants within the ample territory her mate has established. The pair may have the whole field to themselves, but more often a few pairs nest fairly close to one another, forming a small community.

Occasionally, one or more singing males will appear in an area late in July, and it appears that they and their mates are the overflow from a community where there was not enough room for all. Such a situation is described by Cartwright et al. (1937), who also furnish the following on nest types:

The situation of Baird’s sparrows’ nests varies somewhat but is limited in the one respect of being always placed upon the ground amongst the grass. For convenience of description they can be divided into three general types, although it must be borne in mind that this is an arbitrary classification and that the distinguishing characters may not be strictly adhered to from nest to nest.

First comes the type where the nest is placed in a tuft of grass which is usually held up by a wolfberry or other kind of shrub. The tuft is hollowed out, a floor of grass is added, and the sides are then built up with grass woven in and out sometimes to a height of five inches. In another type, the location is chosen beneath an overhanging often horizontal tuft of dead grass, leaving only a small entrance hole at the side. Frequently there is a slight depression underneath the tuft, but if none exists, a shallow one is made by the bird. In the third type, which seems to be the most common, the nest has no overhead concealment. Nests of this type are quite often situated in cavities: generally hoof marks: that in some cases are so deep as to place the nest two or three inches below ground level. If such a cavity is not utilized, however, a shallow excavation is made so that the nest is sunken to the level of the surrounding recumbent dead grass.

Differences in structure are only slight and depend largely upon the type of situation. In the first and second types the floor is composed of short lengths of dead grass laid down to form a sort of thick mat. This is surmounted by a rim of interwoven grass which varies in height, being high in the first case and low in the second. The entrance in the first type is fairly high up in the tuft, where the side is gradually pressed down by the birds in alighting and departing. In the second type the entrance is at ground level, is small, and is usually the only position from which the interior can be viewed. In the third case, if the nest is sunken in the ground, it is then a more substantial affair, being a bulky, wellwoven, cup-like structure.

The average inside dimensions of a nest are: diameter, 2.5 inches; depth, 1.5 inches.

The variety of materials found in the nests is very limited. Dead grass is used almost exclusively, the lining often being of finer strands than the rest. P. B. Peabody in North Dakota and Minnesota, and A. Dawes DuBois in Montana have found that weed stems were sometimes used. No similar observation has been made in our studies. In one nest we have seen bits of a moss that grew sparsely in the vicinity. In the lining of two nests a few strands of horse hair were noticed. Another material often favored where it could be obtained was the red setae of moss, greatly resembling hair and possibly used for the same reason.

The life of the nest is very short, lasting only about three or four weeks. During the course of nesting it suffers greatly from the trampling of both parents and young. Moreover, when the young birds leave, it has been observed by us that the sides are broken down and the material of the nest strewn about so that traces of its existence are obliterated. This must necessarily be done by the parent birds.

The birds are exceedingly close sitters, even on fresh eggs, and will not flush until one is on top of them. One female (on fresh eggs) would even allow a light rope to be dragged over her without flushing. In consequence, the nest is extremely difficult to find. The fact that of the thirty-five nests which are recorded * * *, fifteen of them are ours, the balance being practically all the nests of this species which have been discovered in fifty-eight years, will tell the story of countless hours of searching much more graphically than any words.

There seems to be little variation in nesting habit or situation in any part of the breeding range.

I believe this species delays its nesting activities till late in June because the tough prairie sod is slower to grow the necessary cover. This late start also reduces the probability of a second brood. Normally both parents are caring for their offspring nntil the end of July, after which a second nesting would not be feasible.

Cartwright et al. (1937) give no nesting records for Saskatchewan, but at least three nests have been found there. The first is recorded by W. E. Clyde Todd (1947) from the Last Mountain Lake area: “Dr. Sutton found a nest here on June 23, [1932]; it held four eggs which closely resemble those of the grasshopper sparrow.” Fred G. Bard, of the Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History, collected the second nest with five eggs near Hatfield, Saskatchewan, June 28, 1933. The third, also with five eggs, was found by Manley Callin just east of Percival, Saskatchewan, June 24, 1934. Bearing in mind the vast areas of this province where Baird’s sparrow occurs, it probably nests more plentifully here than in all the rest of the breeding range. Once the field naturalists of Saskatchewan become more familiar with it and its habits, they should find many more nests to study.

Much has been said of the long searches necessary to the finding of nests of this species. To point up this fact, an organized search of one 350-acre field which harbored at least 30 singing males during the first three weeks of July 1962, yielded only two nests of Baird’s sparrow. Over 100 man-hours of intensive search were spent in this hunt, during which 15 active nests of other species of ground-nesting birds were found, despite the lateness of the season. One nest in 1962 had a life history of just over one month: from a nest-scrape made June 18, until the fledglings left the nest, July 21.

Eggs: Oliver Davie (1898) states: “The eggs are laid in June and July and they range from three to five in number * * ‘~.” But Cartwright et al. (1937) found the numbers varied from three to six in the 15 nests they studied, with five eggs the average. They write:

The ground Color of the eggs is white, rarely showing a faint tinge of bluish. Reddish-brown spots and blotches showing a decided tendency to form a wreath about the larger end are the commonest markings. Occasionally there are small black spots and lilac or lavender markings, the latter being probably due to the obscuring of reddish-brown pigment by shell layers. The eggs are not easily distinguished from those of the savannah sparrow, which are variable both in ground color and markings, nor from those of the vesper sparrow, which they closely resemble. They are larger than the savannah sparrow’s and smaller than the vesper sparrow’s as a rule.

Seven of the eight nests I found between 1960 and 1965 contained four eggs as a full set; the eighth held five. The eggs of the first two sets I found in 1962 were wreathed about the larger end; those in the later nests were spotted more irregularly.

W. G. F. Harris writes: “The usual set for the Baird’s sparrow consist of three to five eggs. They are ovate and have only a very slight gloss. The ground is grayish white, but this is frequently obscured by the numerous 51)ots, 1)lotches and speckles of ‘auburn,’ ‘hazel,’ ‘chestnut brown,’ or ‘russet,’ which often cover the entire egg. Underlying spots of ‘light Quaker drab’ are discernible on many eggs, especially on those which have less brown markings. Occasionally, an egg will have a few spots of black. In many of the sets I have examined, the spots and markings seem to be somewhat dull or clouded. The measurements of 50 eggs average 19.4 by 14.6 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 21.8 by 15.2, 20.3 by 16.3, 16.4 by 12.6, and 17.5 by 12.5 millimeters.”

Incubation: Cartwright et al. (1937) made the following observations on incubation:

As mentioned in Table III, the duration of incubation has been found in one instance to be eleven days. No other observations on this point are known to exist. Incubation is performed entirely by the female, which leaves the eggs only for brief periods, at nearly all times returning secretively by mousing away through the grass. She is rarely seen during incubation except at the nest.

Eggs, especially large sets, usually lie in the nest in a definite arrangement. A set of six eggs lying in two rows of three each was several times shifted out of that position, and just as frequently it was returned by the bird to its original order.

During the first incubation period, the male passes the time in the vicinity of the nest, singing and feeding. Neither his voice nor his actions give any indication of the location of the nest, and even when it is in immediate danger of discovery his manner does not change.

I made one incubation check on a nest in 1962; the period between the laying and the hatching of the last egg of the clutch was between 11 and 12 days.

Young: Cartwright et al. (1937) describe the nestling as follows:

Newly hatched young of Baird’s sparrow are clothed with pale smoky-grey down, this being longest and densest on the head (capital tract). Down also shows along the spinal, huineral, alar (between the elbow and wrist) and femoral tracts. By way of contrast, the down of the savannah sparrow is dull mousegrey while that of the chestnut-collared longspur is whitish-grey to huffy-grey.

The skin is reddish-flesh color, translucent (paler and less orange than the young savannah sparrow of the same age). The young are blind for the first three days of their lives but the eyelids begin to Open on the third day in the case of the strongest and most vigorous of a nestful. Development is rapid, the remiges growing more quickly than any other feathers until about the time the young are ready to leave the nest, when general feather growth appears to be retarded except the scapulars which continue to develop steadily.

Iris: rich dark brown; bill: pinkish-grey suffused along the culmen with brownish which intensifies as the young become older; lower mandible pale pink; tarsi, feet and claws: pale pink, translucent.

For the first day or two they lie prone in the nest with the head turned back toward the body. They are so weak that they can raise their heads to receive food only with difficulty. For two days after hatching the female broods occasionally in the daytime, for a period of about three minutes each time. During the night she appears to cover the young every night until they leave. On the fourth day the young birds begin to utter a faint peeping noise. By the fifth day they have acquired sufficient strength to stand up in the nest when being fed. On this date they begin to use a “taepe” note as a food call.

Young Baird’s sparrows depart from the nest on their eighth to tenth day. By then they are well feathered, wide awake, and active, although incapable of flight. They usually leave together, the struggling of the first bird being a sufficient stimulus to urge them all to action. They crawl rapidly away and hide in the grass, where they are lost to view for the next few days.

By about the thirteenth day of their lives they are able to fly for a few yards. One bird at this stage was found lying in a small cup-like hollow almost like a nest. When they are about nineteen days old they have developed to the point where they begin to wander away from their parents’ territory. At this time they begin to utter a thin “secep” which appears to be a flocking note.

My observations show that the mother cares for the hatchlings alone for the first several days. She feeds them, broods them, and removes and eats all excreta. Then her mate usually comes to her aid. At a nest I found in 1965 the father had only one eye. Despite this handicap he proved a model spouse and did his full share of feeding and brooding the young and cleaning the nest. Daytime brooding ceases on the fifth day after hatching.

After the young leave the nest, both parents continue to carry food to them. Though the flightless young never travel more than a few yards from the nest area, for the first day or two the parents seem to have difficulty locating them, and hover on threshing wings until a tip! call from a youngster guides them to earth.

Plumage: Cartwright et al. (1937) give the following description of the juvenal plumage:

Loral region and forehead black sparsely tipped with buff; crown black tipped with buff, more huffy in the center, showing an indistinct median line; superciliary line buff; auriculars buff tipped with black; malar region buff, nape and hindneck black edged with buff; back black edged with pale buff, giving a scaly appearance; rump black edged with ochraceous-buff; upper tail coverts and rectrices the same; scapulars black edged with buff, paler at the tips; primary and secondary coverts greyish-black; throat and upper breast black widely edged with buff, the same pattern continuing along the sides; belly white tinged with buff, paler toward the vent; undertail coverts white; crural tracts whitish with black centers. The general coloration of the juvenal is ochraceous buff about the head, a mixture of blackish and ochreish on the back giving a scaly appearance. The colors are more intense than any plumage of the adult and the breast and side markings are heavier.

A thesis by R. R. Graber (1955) compares the juvenal plumages of Ammodramu.s as follows:

The two species of this genus, savannarum and bairdi are very much more alike as juvenals than as adults. Adult bairdi bears a striking resemblance to the savannah sparrow, Passerculus sandwichensis, and Ridgway (1901) placed the species in a montypic genus, Centronyx, between Pcssercutus and Coturniculus (= Ammodramus), stating that it was much closer to the latter. He did not mention the juvenal plumage in his discussion of the relationship of the three forms, but the characters of the juvenal support his view that bairdi and savannarum are close. Certain patterns are common not to juvenal or adult savannarum but to juvenal sevannarum and adult and juvenal bairdi. I refer particularly to markings on the chin and side of the head and the conspicuous ventral streaking. Juvenals of both species have a scaled back-pattern. This pattern appears to be an adaptive feature in prairie birds, but juvenal Passerculus does not have it, despite the fact that Pcsserculus and Ammodramus are prairie associates in the many areas throughout which their ranges overlap.

A striking feature of the juvenal plumage in Ammodramus is its firm texture. In this respect, the plumage is like that of the adult. This is particularly true of bairdi, in which the juvenal plumage appears to be long-lived. The occurrence of juvenal specimens and worn adults in Arizona has led to speculation concerning a discrete southern breeding range. Among the many bairdi records listed by Cartwright, Shortt and Harris (1937) were several southern records of juvenals. In every case these were late August or September records. I have seen three such specimens, worn birds in the early stages of the postiuvenal molt. Such specimens are not reliable evidence of breeding, though stub-tailed juvenals would be. The number of records of juvenals south of the known breeding range of bairdi indicates that this species migrates often, and probably regularly, in juvenal plumage. This is also true of Leconte’s sparrow, Ammospiza lecontei, though the two species are not particularly closely related. Ammodramu8 savannarum appears to complete its molt before migrating, but this is difficult to prove. Because of the much broader range of savannarum, migration of juvenals in this species can be proved only through banding.

In both species of Ammodramu8 there is a precocious development of winter plumage in the scapular region of the upper back, but the bulk of the juvenal plumage is retained until well after the first flight feathers are grown. Sutton (1935, 1937) discussed the development of the juvenal plumage and the early stages of the postjuvenal molt in scvannarum. Dwight (1900) described the molt of this species as complete, and mentioned a partial prenuptial molt (spring) involving mainly feathers of the head and anterior portions of the body. There is a similar spring molt in A. bcirdi, as indicated by the only adult specimen at hand, but I have found no published data on the molts of this species.

The nearest ally of Ammodramus is probably Passerherbulus henslowi. The three species are similar in habitat, and all have a scaled back pattern in juvenal plumage. Their molts are similar, so far as I know. The underparts of juvenal Passerherbulus are immaculate, of juvenal Ammodramus, streaked.

T. M. Shortt (1951) compares the juvenal plumage with that of 2 other species:

A circumstance that struck me forcibly while collecting specimens of juvenile birds in the prairie region of Manitoba was the similarity in juvenal plumage of three species of birds, representing two families, that were closely associated on the nesting grounds. I refer to Sprague’s pipit, AaIhus spragueii, Baird’s sparrow, Ammodramue bairdii, and chestnut-collared longspur, Calcarins ornatus, all of which have a “scaled” pattern on the dorsal area. This was considered somewhat remarkable, especially since the “scaled” juvenal plumage is not common among the Fringillidac and since another species of Caicarius (C. lapponicus) has the dorsal surface streaked.

The implication seemed to be that there may be some survival value in a “scaled” dorsal plumage for prairie-nesting passerine birds, though why it should be more advantageous than a streaked plumage is not obvious.

T. S. Roberts (1932) gives the following description of the adult plumage:

Top of head and nape a rich, strong buff or brownish-yellow, striped with black, especially on sides of crown and nape; sides of head and neck pale buff, more or less flecked with black; a narrow line of black spots on side of throat; feathers of back dull black centrally, margined with grayish-white or pale buff, producing a streaked appearance; rump lighter, more buffy; underparts white or pale buff on throat and breast; streaked on sides, flanks, and across breast with black, the streaks on breast sharply defined and forming a necklace, those on sides more diffuse and tinged with rufous; wing feathers greyish-brown, the coverts darker centrally, all edged with pale rufous; 2 not very distinct wing-bars; tail dull brown or blackish, the outer feather on each side narrrowly edged with white outer web and pale, dull white terminally, suggesting a white outer tail-feather when seen by transmitted light; the other feathers narrowly tipped with dull white or buffy, bill light flesh color, darker at tip; legs flesh color, feet darker; iris brown.

The middle pair of tail-feathers is much narrower and more pointed than the others.

Two female adults, taken at Gardner Wash, Ariz., by 111. Johnson and P. J. Gould, Feb. 6, 1960, weighed 17.0 grams and 17.8 grams respectively. Six males taken by a field party from the University of Minnesota in Clay County, Minn., in July 1961, had an average weight of 18.6 grams, an average length of 135.6 millimeters, and an average wingspread of 236.3 millimeters.

Food: The food of this species varies with the seasons. During their winter sojourn in Mexico, weed seeds must form the main diet, as they do in Texas. Mrs. Harold L. Williams writes me from Midland, Tex.: “They are usually seen feeding on the ground in fields of maize stubble. ‘Maize,’ or ‘milo,’ in Texas refers to the several varieties of grain sorghum grown as food for cattle. Baird’s sparrows have also been seen in patches of tall ‘careless weeds,’ (Amaranthus sp.).”

When Richard and Jean Graber encountered Baird’s migrants near Norman, OkIa., in April 1953, some of the common plants in the field where the birds occurred were: red three-awn (Aristida), little bluestem (And ropogon scoparius), brome (Bromus), six weeks’ fescue (Festuca octoflora), yellow sweet clover (Melilotus ofticinalis), perennial ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya), plantain (Plardago virginica), blazing-star (Liatris), and evening primrose (Oenothera taciniata).

Stuart Criddle writes me that: “The food of our Manitoban sparrows changes sharply with the seasons. In the spring and fall a great variety of seeds are eaten. These include: “Lamb’s quarters (Cheno podium album), Russian pigweed (Ax yris amaranthoides), Russian thistle (Salsola Icali), redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), false flax (Camelina microcarpa), tumbling mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) , and green foxtail (Seraris viridis). This last-named plant probably produces more food for the sparrows, longspurs, and horned larks than any other weed.”

In summer, adult Baird’s sparrows take spiders and numerous varieties of insects and their larvae, and Cartwright et al. (1937) show that these are the only food they give the young. Part of their account follows:

Our astonishment was great when we found young birds but two days old being fed with unmodified grasshoppers. * * * Later, specimens of the grasshoppers present in the area were collected and submitted to Mr. Norman Criddle, together with a moth and a cricket which were occasionally fed to the young. We are indebted to Mr. Criddle for the following identifications: Orthoptera: Chorthip pus curtipennis Harr; Camnula pellucida Scud; Arphia pseudoneitana Thoms; Melano plus dawsoni Scud; Melonoplus bivittetus Say; Gryllus assimilis Fab; Lepidoptera: Caenurgia erechtea Cram.

Mr. Criddle points out that C. pellucida and Al. bivittatus are pests of economic importance.

It is of interest to note that, while the young are fed almost entirely on large grasshoppers, the food of adults in summer consists mainly of smaller insects. The examination of the stomachs of four adults reveals only one small grasshopper nymph, but many small items such as leaf-hoppers, spiders, moths and small seeds are present. It would seem that the adult, in searching for food for the young, consumes all the small insects it comes across which are not worthy of a trip back to the young. Thus the “by-products” of its search for food for the young are, in effect, a natural economy during the period when the demands on the adult are great.

The foregoing data were gathered during the early 1930’s, when severe drought conditions probably curtailed the varieties of food available, but in 1962, small green caterpillars formed the whole diet for the first 5 days of the fledglings’ life, and even after the parents began bringing small grasshoppers to the nest on the sixth day, caterpillars and moths still formed a large part of the daily food.

Behavior: The outstanding behavior characteristic of Baird’s bunting was noted the day the species was found. Audubon (1844) wrote: “Several times Mr. Bell nearly trod on some of them, before the birds would take to wing, and they almost instantaneously re-alighted within a few steps, and then ran like mice through the grass.~~ This reluctance to fly is typical of the bird at all seasons. Allan R. Phillips of Arizona, reporting data on four wintering specimens of Baird’s sparrows taken in Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico, writes me: “All of these were lone birds, running mouselike in open grassland.”

On the summer territory the male spends the incubation period patroling his home grounds, singing, feeding, and generally enjoying the good life. The appearance of a hunting harrier hawk or shorteared owl will cause him to lapse into silence and prudently take cover in the ground vegetation. Sometimes, when the tinkle-bells are silent, the entrance of humans into a field will immediately result in the males resuming their singing, almost as though the birds wanted to warn the intruders they were violating private property.

The Baird’s sparrow has an equable disposition and gets along well with his neighbors. Only once have I seen one act aggressively toward another species. While perched on a fence post singing to his hidden mate, a Baird’s male suddenl3~ broke off to pursue a claycolored sparrow that had alighted on a strand of fence wire close by. He returned shortly and spent five minutes preening his ruffled feathers and regaining his composure. Then he resumed the serenade, his throat pulsing and body quivering from the effort.

On rare occasions a male Baird’s sparrow will leave an elevation and coast to the ground, singing as he goes, and continue the serenade from his new position.

He appears to be rather tardy in aiding his mate in the important chore of providing food for the nestlings, for I have heard him still singing his regular matins and vespers several days after the young appeared. However, the sangfroid with which he views the efforts of searchers to find the nest disappears after the young are several days old, and he will then join his mate in their defense. This is corroborated by Gordon Smith, of Winnipeg, Manitoba, who noted at a nest observed July 22, 1961: “Nest holding three fledged young found in grass 8: 12 inches high. Both adults present, chipping excitedly.”

While brooding the young in hot weather, the parent may start to pant and then lift the back feathers away from the body, apparently to coo1 itself, starting with the tail coverts and progressing up the back to the nape and crown. This gives the head a spectacular crested appearance, in sharp contrast to the usual low profile. After a few moments the bird settles the feathers into place again by reversing the action, the crown first resuming its normal outline.

Voice: Audubon and his companions, on first hearing the notes of this little bunting, thought they were produced by marsh wrens, and Coues (1873) compared the song to that of the Savannah sparrow. In a later volume he (1903) wrote: “Song peculiar, of two or three tinkling syllables and a trill, like ‘zip-zip-zip-zr-r-r-r’.”

Actually, of all the so-called “grass sparrows,” Baird’s sparrow has, to my ears, by far the most pleasing song: much superior to the sibilant gasp of the grasshopper sparrow, to the nearly inaudible hiss of Le Conte’s sparrow, to the broken sigh of the Savannah sparrow, or to the guttural ejaculation of Nelson’s sharp-tailed sparrow, and infinitely preferable to the hiccups Henslow’s sparrow uses for a song. Though neither loud nor impressive, the refrain is still a pleasant combination of opening notes and ending trill.

The song is in two distinct parts, each of which may vary somewhat in duration and composition between individual birds, and no two listeners hear it exactly alike. Though each male has his own idea of just how the song should be given, the “normal” presentation is three or four opening notes followed by a trill of five or six “beats,” thus: Dee-dee-dee i-i-I-I-i. The last part of the song, the trill, is a half to a full tone lower in pitch.

The first part of the melody, a repetition of the one note, has a breathless, tinkly timbre. The second part is a pulsing trill, almost a warble, and it has a clear, sweet quality that makes it thoroughly entrancing. There is no perceptible break between the two sections of the refrain, other than a connecting half-note, and the entire outpouring is one entity, despite the sudden lowering in pitch. Under favorable conditions the song can be heard 250 yards away, with the ending trill carrying even farther.

When a male has fallen into a pattern of territorial song, he gives his refrain six to eight times a minute. Morning and evening find him in best voice. At other times, his singing is spasmodic and he will of ten lapse into a silence for an hour or more, unless disturbed.

The female does not sing, but gives a high chip and sometimes a low, crooning tr-r-i-p note when danger threatens her young. The male’s similar note is much deeper. The low, murmuring, Meeerr-meeer-r sound noted by Cartwright et al. (1937) is apparently an expression of endearment. It may be uttered during copulation, though this has never been proved. Both parents utter it when approaching the nest after the young begin to call for food on their sixth day of life. The nestlings soon give voice to a stronger tip note, and when one was lifted from the nest on the eighth day of life, it gave a loud, squalling cry. Tha species has the usual chipping flock call in migration.

I have noted earlier that familiarity with the song of the Baird’s sparrow is the best means of locating the bird in the field. Two recently issued song recordings, “Finches,” by Donald J. Borror and William W. H. Gunn (1960), and “Prairie Spring,” by W. W. H. Gunn (1962), include excellent reproductions of the variable melodies of the species. Such recordings will prove of great aid to all who wish to become acquainted with this lovely little finch.

Field marks: A. bairdii strongly resembles A. savannarum and other closely allied genera. Allan R. Phillips tells me by letter that: “In Mexico I once chased a remarkably pale, huffy sparrow for a long time, in September, sure that it was a Leconte’s, Baird’s, or some other rarity. I finally got it, and it proved to be just a washed-out, freakish Savannah!” In my experience, the ocherish patches on Balrd’s sparrow’s head and neck are not apparent, even through good glasses, unless the bird is at close range. At greater distances a back view shows a slim, dark bird, and when it turns to face the observer, the shining, grey front resembles that of a pale Savannah sparrow, which as a general rule looks much darker.

Like the grasshopper sparrow, the other member of the genus, Baird’s sparrow has a flat-headed silhouette which aids in identification. The low, hurried flight across the grass and sudden pitch to earth is another good mark, though not an infallible one.

Since the sitting hen is invariably flushed from the nest at very close range, it is often possible to note the pale-yellow margin on the two outer tail feathers.

Enemies: Among the dangers confronting the prairie-dwelling species of birds, fire and the plow are the most serious, and the effects of the plow are even more profound and lasting than those of an allconsuming fire. Land eventually recovers from a scourge of flame, but that once turned by the plow is usually lost forever to groundnesting birds.

Among the mammals, the larger animals such as horses and cattle occasionally trample a nest, but losses from this are negligible. The smaller animals are the most deadly, and Stuart Criddle writes me that “The mammals known to prey on our ground-dwelling birds can be placed in the following order, the smallest first-named: Baird’s white-footed mouse (Peromyscus maniculatu.s bairdii), Drummond’s vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus drummondii), thirteen-lined ground squirrel ((‘itellus t. tridecemlineatus), short-tailed ermine (Mustela erminea ban gsi), prairie long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata ion gicauda), least weasel (Mustela r. rixosa), northern plains skunk (Mephitis mephitis hudsonica), plains coyote (Cartis 1. latrans).”

Of the above list, the three rodents are frequent raiders of grassland nests, but are often content with just one or two of a brood. However, when raiding nests in tufts of grass above ground level, both voles and white-footed mice often drill holes in the bottom of the nest that allow all the contents to tumble through to their doom. The weasels and largers predators are never satisfied with less than the entire contents of the nest.

Concerning the effect of raptors on the ground birds, Stuart CriddIe’s letter continues: “While most of our hawks in T’Ianitoba take a few prairie birds, the marsh hawk is the most persistent hunter and captures more young sparrows and other small birds than all the other hawks together. I have often watched a harrier chase a sparrow, knock it down with a sharp blow of a wing, then turn like a flash and pounce on the half-stunned bird before it could recover and fly again.”

James A Munro (1929), reporting on the nest of a marsh hawk, writes: “A beheaded juvenile Baird’s sparrow in nestling plumage was the only food at her nest.” Glen A. Fox writes from Saskatchewan that: “I checked an active nest of Richardson’s merlin, July 9, 1961. Thirteen tarsi were removed from the nest, and Donald R. Baldwin of the Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology identified one as that of an immature Baird’s sparrow.”

A. bairdii is fortunate in one respect: nesting as it does in wide, open grasslands, it shares with several neighboring species almost complete immunity from the visits of that parasite, the brownheaded cowbird. This bird prefers to lay in nests located in brush or tree growth, and I have never found the nest of a prairie horned lark, a Sprague’s pipit, or a chestnut-collared longspur victimized by it, The western meadowlark is usually exempt also, and not until 1962 did I find a nest of this species that had been visited by A’folothrus ater, two of the six eggs being strangers. This nest was within a few feet of fairly heavy bush growth, which probably afforded the hen cowbird the opportunity she seldom misses when a nest is near such cover.

Cartwright et al. (1937) report two cases of Baird’s sparrow being victimized by the brown-headed cowbird. The first was reported by Roberts (in litt.) from North Dakota June iS, 1883. The second was a nest R. D. Harris found at Winnipeg, Manitoba, July 7,1931 with three Baird’s sparrow eggs; the following day a cowbird egg had been added to the clutch, which Harris removed. In addition to citing these two records, H. Friedmann (1963) lists two parasitized bairdii nests collected by L. B. Bishop in North Dakota, and two others without definite locality data. In writing me of these he comments: “the fact remains that Baird’s sparrow has been recorded hut seldom as a host of the cowbird.”

Fall: As summer wanes, the tinkle-bell pealings of t.he males gradually fade away and Baird’s sparrow once more assumes its will-o’-the-wisp character. This lapse into silence usually coincides with the appearance of the fledged young.

Where the hatch is late, the young may not be on the wing until mid-August. When leaving their birthplace they are usually accompanied by their parents. They wander about the countryside in little family groups while the juvenile wings strengthen for the fall migration. As dates of latest sightings on the summer range vary from mid-September to late October, the autumn leave-taking extends over a 5- to 6-week period.

In early August, while the main population of Baird’s sparrow is still in the north, some juveniles and adults in worn breeding plumage occasionally appear on the fringes of the winter range. This led to speculation at one time on a possible breeding population on the high grassy plateaus of New Mexico and Arizona. However, Richard R. Graber (1955) points out that only the presence of stub-tailed juveniles would lend credence to this suggestion, and that these have never been found in the southwest.

Winter: Baird’s sparrows spend the winter months in their usual inconspicuous manner, wandering about alone or rarely in twos or threes. Allan R. Phillips writes me from Mexico that: “The species is never found in flocks, so far as my knowledge goes. Nor have I heard any of them sing.

While most of the population continue their migration until they reach northern Sonora (south of Sasabe), Durango (Ojito), and Coahuila (Saltillo), a few remain in the southwestern United States in western Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. In Arizona their numbers vary greatly from year to year, according to Gale W. Monson (1960) who states: “Baird’s sparrows, usually very rare in Arizona, were almost common in some localities; they were collected at Gardner Canyon on the east side of the Santa Rita Mts., Feb. 6 and April 10 (U. Roy Johnson), 1960; 1 was seen along Rillito Creek near Tucson, Dec. 6, 1959 (Thornburg), and 4 were noted on the Tucson Christmas count, Jan. 2, 1960.” Despite these recent records, Monson also writes me that: “The picture of Baird’s sparrow in winter is indeed a cloudy one. Many, or even all sight records, are very unsatisfactory and must on the whole be disregarded.” A letter from Roger T. Peterson adds: “Obviously there are very few definite records for Mexico.”

DISTRIBUTION

Range: High plains from southern prairie provinces to north central Mexico.

Breeding range: Baird’s sparrow breeds from southern Alberta (Castor), southern Saskatchewan (Crane Lake, Kutawagan Lake), and southern Manitoba (Oak Lake, Grand Rapids, Lake St. Martin) south to northwestern Montana (Dutton), northwestern and central So~S Dakota (Harding County, Eureka), southeastern North Dakota (northern Sargent County), and central western Minnesota (Wheaton).

Winter range: Winters from southeastern Arizona (San Rafael Valley, Sonoita, Chiricahua Mountains) and southern New Mexico (Animas Valley) south to northern Sonora (10 miles south of Sasabe), Durango (Ojito), and Coahuila (Saltillo); in migration to western and south central Kansas (Pendennis, Udall), central Missouri (Columbia), central Oklahoma (Cleveland County), and western and central Texas.

Casual reeords.: Casual in southern California (Joshua Tree National Monument). Accidental in New York (Montauk).

Migration: Early dates of spring arrival are: Arkansas: Winslow, March 23. Missouri: St. Louis, March 17. Ohio: Ottawa County, April 22. lowa: Grinnell, March 24. Minnesota: White Earth, Becker County, May 5. Oklahoma: Inola Prairie, April 12. Nebraska: Holstein, March 28. North Dakota: Billings County, April 25; Jamestown, May 5; Cass County, May 6 (average, May 17). Manitoba: Treesbank, April 21; Whitewater Lake, average May 9. Saskatchewan: Dinamore, April 19. New Mexico: Rodeo, April 9. Arizona: Tucson, April 21. Colorado: Fort Lyon, April 1. Wyoming: Torrington, May 2. Montana: Missoula, April 20; Fallon, April 24. Alberta: Castor, May 10.

Late dates of spring departure are: Missouri: St. Joseph, May 25. Texas: ~Gainesville, April 24. Arizona: Cochise County, May 4; base of Huachuca Mountains, May 3.

Early dates of fall arrival are: Arizona: Ash Flat, August 15. New Mexico: Upper Pecos, August 11. Texas: Gainesville, September 26.

Late dates of fall departure are: California: Joshua Tree National Monument, October 3. Montana: Terry, September 10. Wyoimng: Midwest, September 19. Colorado: Colorado Springs, November 26. Arizona: Rincons, October 24. New Mexico: Gila River, October 16. Saskatchewan: Rosetown, September 7. Manitoba: Treesbank, October 5. North Dakota: Billings County, October 21; Union County, October 15. South Dakota: Faulkton, October 15. Nebraska: Holstein, November 8. Oklahoma: Edmond, November 24. Texas: Bonham, November 5. Minnesota: Hallock, September 11. lowa: Grinnell, October 16. Missouri: St. Louis, October 29.

Egg dates: Alberta: 5 records, June 9 to June 23~ Manitoba: 10 records, June 6 to August 11.

Minnesota: 2 records, June 7 and July 22.

Montana: 2 records, July 18 and July 20.

North Dakota: 9 records, June 5 to July 15.