With a relatively limited usual range in the lower 48 states of the U.S., the Barrow’s Goldeneye is a prized vagrant to find on a winter birding trip in many states. Barrow’s Goldeneye breeding territories are defended by males, and some pairs also defend winter territories, though lone birds are often seen in winter with flocks of Common Goldeneyes.

As for most ducks, weather, disease, and hunting are major mortality sources. Individual birds can live a long time, with the known record for a bird in the wild being over 18 years old. Barrow’s Goldeneyes have a fairly strong tendency to return to the same breeding area year after year.

On this page

Description of the Barrow’s Goldeneye

BREEDING MALE

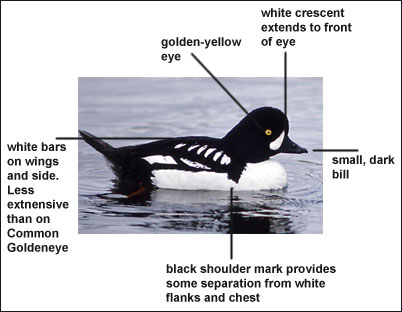

Oval-shaped head with a steep forehead. It has a short, triangular bill. White underparts. Purplish head with crescent-shaped white face patch between eye and bill. Row of white stripes or spots on the scapulars. Length: 18 in. Wingspan: 28 in.

Female

Grayish-brown body with a brown head and yellow bill.

Seasonal change in appearance

Eclipse plumage males resemble females.

Juvenile

Similar to adult female.

Photograph © Glenn Bartley.

Habitat

Lakes with nearby trees for nesting, as well as large rivers and coastal areas.

Diet

Crustaceans, mollusks, fish, marine worms, frogs, and insects.

Behavior

Forages underwater by diving.

Range

Breeds primarily in Canada, Alaska, and parts of western U.S. mountains. Winters along northern coasts and in parts of the western U.S. Population trend is stable.

Fun Facts

Because large trees are required for suitable nest cavities, nest boxes can be a useful way to increase the number of nest sites in some areas where cavities are scarce.

Females often lay eggs in each other’s nests, sometimes resulting in unusually large clutches and will use nest boxes for breeding.

Vocalizations

Females make soft “cu-cus” to broods and males may grunt during courtship.

Similar Species

Common Goldeneye

Common Goldeneyes have a subtly different head shape and less steep forehead. Males have a round rather than crescent-shaped facial spot, and a greenish head gloss. Females usually have dark bills.

Nesting

Nests in tree cavities or nest boxes.

Number: 7-10.

Color: Greenish or blue-green.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at 29-30 days.

– Young fledge (leave the nest) in 1-2 days but remain with the female for some time.

Bent Life History of the Barrow’s Goldeneye

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Barrow’s Goldeneye – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

GLAUCIONETTA ISLANDICA (Gmelin)

This species has been well named, the Rocky Mountain goldeneye, for outside of the vicinity of the Continental Divide in the northern States and in southern Canada it is nowhere in this country an abundant species at any season. It is so rare throughout most of its American range that few ornithologists have ever seen it in life.

For this reason it is not strange that it was overlooked by some of the earlier writers and that until recently its distribution was so poorly understood. Wilson makes no mention of the species, and it was entirely overlooked by Audubon, who may have regarded it as a summer plumage of the common species. Even Coues (1874) refers to it as “the most northerly species of the genus, having apparently a circumpolar distribution, breeding only (?) in high latitudes, and penetrating but a limited distance south in interior”; the question mark is his and it is interesting to note that his doubt was removed by finding it breeding in the Rocky Mountains of Montana. It is now known to breed in these mountains as far south as Colorado. east in Canada to the north shore of the St. Lawrence, in Greenland, and in Iceland; but it is far from being circumpolar, for it occurs on the Old World continent only as a stragler and it is not known to breed north of the Arctic Circle.

Courtship: J. A. Munro (1918) has given us an interesting account of this species, in British Columbia, from which I quote as follows:

The birds first begin to appear on Okanogan Lake early in March, but are not plentiful until the small mountain lakes are free of ice, early in April. The lakes selected for courtship, and later for the rearing of the young, are usually quite open and free of tules; hence the goldeneyes are always conspicuous an(l much easier to study than ducks that breed in the sloughs and hide their young in the thick vegetation. Generally by the 15th of April each little lake has its flock of courting goldeneyes, often 30 or 40 on a sheet of water of 50 acres extent or less. In these flocks adults and immatures are present in about equal numbers. The young of either sex do not breed until the second year, and do not assume their breeding dress until the second fall after they are hatched; that is, when they are over a year old.

The courtship display is witnessed in the flocks just prior to their splitting up into pairs. It is attended by much solemn bowing on the part of the drake, with a frequent backward kick, sufficiently strong to send a jet of water several feet into the air. His violet head is puffed out to the greatest possible extent, and altogether he is a handsome bird as, in a frenzy of sexual excitement, he swims up to the soberly attired duck. Sometimes the entire flock will commence to feed as if at a given signal, and again all the birds will simultaneously take wing and circle about the lake several times before once more splashing down to resume their courtship.

He also contributes the following note:

Two mated pairs in a small lake in the hills ~vere under observation for two hours. The males acted as if extremely jealous of each other and on several occasions left their mates and engaged in spirited encounters. They rushed together over the surface with much splashing, and when about to meet rose upright and buffeted each other ~vith their wings. A female, whose mate had been killed on an adjacent pond, flew into this lake and immediately one of the mated drakes left his mate and dropped in beside her, when he began bowing, but the strange female did not respond. The male then dove several times trying to rise beneath her, at ‘vhich she flew some distance away and the drake then rejoined his mate.

M. P. Skinner contributes the following:

Early in the winter the ducks outnumber the drakes; but as spring approaches the proportion becomes more equalized. By February 1 the tendency of the flocks to pair off becomes noticeable; courting begins about the same time and lasts until June in some cases. Almost all the flocks are broken up by April 1. While the drakes do most of the “chasing” and “dancing,” the females sometimes go through similar movements. The drake swims across the water with jerky motions, not necessarily toward the duck, occasionally an extra kick raises the breast above the surface and at the same time the bill is pointed up and opened and shut twice. Then the neck is stretched backward until the head rests on the lower back, then forward to the normal position, ending with a kick backwards that throws up a little spurt of water. The duck is frequently chased by the drake, with his head and neck stretched out horizontally in front and almost on the water surface.

Nesting: Dr. T. M. Brewer (1879) published an interesting paper on this species which added greatly to our knowledge of it at that time. Edwin Carter, “who was probably the first to actually secure the nest and eggs of this species within the limits of the United States,” sent to Doctor Brewer considerable information about the breeding habits of the Barrow goldeneye in Colorado. He says:

They nest in hollow trees, and it is surprising to see to what small cavi (1877) I have examined a great many trees, and every one that had a suitable opening either contained an occupant or indicated recent nesting by eggshells and other marks.

Maj. Allan Brooks (1903) found the Barrow goldeneye breeding quite commonly in La Hache Valley, in the Cariboo district of British Columbia. He says:

One set of eggs was taken from a hole In a dead Douglas fir, 50 feet from the ground, probably the deserted nest of a flying squirrel. The tree stood about 400 yards from the nearest water. The eggs (7) at this date (17th June) contained large embryos. I saw another nesting hole but was unable to reach it. ¶Ltle female brought 14 young ones out from this.

Mr Munro (1918) says of the nesting habits of this species:

By May 1 all breeding birds are mated and scattered over the country, seldom more than one or two pairs on a inke. The Barrow goldeneye shows a marked predilection for lakes that are strongly alkaline, even if they are poor in aquatic vegetation and in the midst of an open country with the nearest timber a half mile or more away. Such lakes are rIch in small crustaceans, the chief food of this duck, and no doubt the lakes are occupied on account of the food provided, without reference to the availability of nesting sites.

An abandoned flicker’s hole Is usually selected for the nest, frequently In a dead yellow pine, for in this tree decay is rapid, and the hole soon becomes much enlarged. One can generally tell if the hole is occupied, by the fragments of down adhering to the rough bark at the entrance. The tree Is often so much decayed that a single tug at the bark near the hole will remove the whole adjacent surface, exposing the gray-green eggs where they lie in the clinging soft down. It is rather hard to locate the nest when the tree selected by the bird is In heavy timber a half mile or more from the lake, but when the female is sitting it may be done by making an early morning trip to the lake, remaining under cover, and waiting for her to come to the lake to feed. She generally arrives between 9 and 11 and immediately joins the drake. After splashing and preening her feathers, she feeds most Industriously for perhaps an hour and then flies directly back to the nest. I include here data for three nests taken in the Okanogan region.

Okanogan, British Columbia, May 12, 1916. A nest containing 11 fresh eggs was found in the hayloft of a deserted log barn, on the shore of a lake. The eggs were placed In a hollow scooted in the straw under a heavy beam which rested on the piled-up straw. The loft was well lighted through the spaces between the logs and hy a large opening at one end. This situation is of course, most unusual, but it had apparently been used some years before the nest was found. I had seen broods of young on this lake in previous years, when I was not able to find the nest. The birds would generally alight on top of a chimaey in an unused house close by before flying into the barn.

Farneys Lake, Okanogan, May 31, 1912. A nest with seven partly incubated eggs was placed in a large cavity in a yellow-pine stump, standing In 8 inches of water on the shore of the lake. The cavity containing the eggs was 18 inches above the water, and the eggs were in plain view of a person standing several feet away.

Rollings Lake, May 26, 1917. A nest containing seven fresh eggs was found in an old fir stub standing In 18 inches of water near the shore of the lake. The top of the stub had rotted out to a depth of 2 feet and the eggs were at the bottom of this cavity. Down could be seen protruding through a small hole in the stub, a few inches above the eggs.

John G. Millais (1913) says of the breeding habits of this species in Iceland:

Barrow’s goldeneye arrive at their breeding places about the end of March, in flocks, and at once proceed to pair. I have been unable to discover any ornithologist who has seen the courtship display of this species, but I have little doubt that when we are able to procure specimens alive from Iceland, and keep them in good health, we shall find that it is much the same as that of the common goldeneye. The nest is usually placed in a hole in the bank of a stream flowing into a lake, in a hole in the lava rocks close to the water, or on some low island under bushes of dwarf willow, dwarf birch, amongst coarse grass or low scrub, such as Empetrum nigrum or Azalea procumbens. I found two nests just tucked in under large stones, and not 2 feet above the level of the stream. They are also said to nest in the turf walls of the sheep shelters.

He also qilotes Riemschneider as saying:

The nest was always placed in more or less of a hollow, in natural hollows of the rocks, in covered-over cracks in the lava, or, as already mentioned, in the outer walls of peat shelters, erected for sheep, where a few blocks of peat have been taken out to form a nesting place, and even, and that not seldom, inside the shelter, in which case the food rack or a place like it would serve as a nesting place; as exit for flight the door of the shelter would in such a case be used. Such customs have given rise to the Iceland names for the species. In the natural hollows, holes in the rocks, fissures, etc., the nest is placed now in the foreground, now so far inside that you could not reach to it from the entrance opening, but were obliged to lift off the stones covering it for this purpose. Whilst as a rule the position of the nest is to be found approaching the level of the surface of the ground, I saw a nest in the Kalvastrond which was built in a hollow in the lava at more than twice a man’s height. In the nest trough, which was formed to begin with in the food racks of the stalls, by pulling together dry grass stalks and other remnants of food round the nest, there was a very ample, delicate lining of whitish down, which had a very small admixture of fine, dry parts of plants. The eggs, 12 to 15 in number, and only exceptionally more, are distinguished from other ducks’ eggs by their pure, blue-green color, are rather bulgy in shape, and have a smooth, not very shining shell.

From the above accounts it will be seen that the Barrow goldeneye prefers to nest in hollows; the absence of suitable trees in Iceland forces it to select other cavities: but in this country it seems to nest in situations similar to thQse chosen by the common goldeneye and, like that species, it lines the nest cavity with pure white down, scantily at first, but lnore profusely as incubation advances; probably no other material is brought into the cavity, but undoubtedly whatever material it finds there is not wholly removed. The down in the nest is indistinguishable from that of the common goldeneye.

Eggs: The set consists of anywhere from 6 to 15 eggs, but probably the usual number is in the neighborhood of 10. The eggs are practically indistinguishable from those of the common goldeneye, though they may average slightly larger. The shape varies from elliptical ovate or elliptical oval to nearly oval. The color varies from “deep lichen green” to pale olivine” or “pale glass green”; when freshly laid some of the darkest eggs may approach a pale shade of “malachite green.” The measurement of 79 eggs, in various collections, average 61.3 by 44 millimeters: the eggs showing the four extremes measure 66.6 by 42, 61 by 47.2, 57.3 by 42, and 61.9 by 41.4 millimeters.

Rev. F. C. 1?. Jourdain, who has studied the Barrow goldeneye in Iceland, writes me that incubation is performed by the female alone and that it is said to last for four weeks; he says that the female sits very closely and at times has to be removed by force, if one wants to see the eggs. The male remains close at hand during incubation.

Mr. Munro. however (1918), writes:

Immature males leave the country with rue adult males iu May, soon after the females have begun to brood their eggs. I have never seen an adult male at this season. Mr. Allan Brooks is of the opinion that the males go directly to the coast at thus uiiic.

Young: He says of the young:

May 22 is the earliest date on xvhiich I have seen the young, and by August 1 they are full grown. At Ibis time they are remarkably tame, allowing an approach to within a few yards and then, if alarmed, swimming to the middle of the lake, rather than liking xviiig. This fearlessness is characteristic until the shooting season opens iii Septeniher, when they soon become wary. At this time. the birds rise froia the water as one approaches, but almost invariably circle about the lake several times and then thy to~vard anyone stand. lag on the shore, thus affording an easy shot. By the last week in October, when the common goldeneye. redhead, and seaups are returning from the north, the last of the harrow goldeneyes have left.

Plumages: Thc downy young of the Barrow goldeneye is very much like that of the common goldene~e. The upper half of the head, from heloxv the eyes, and the hind neck are deep “bone brown” or ” seal brown ” the upper parts are ” bone brown,” relieved by white on the edge of the wing and by scapular and rump spots of white; the lower half of the head and the under parts are white; there is a brownish gray band around the lower neck.

The plumage changes are similar to those of the common goldeneye. Of the development of the plumage in the young male, Mr. Millais (1913) says:

Ia November the new inner scapulars appear, and these at once give a char. acter to the identification of the species. The black portion of the inner rapulars is much extended in Barrow’s goldeneye, whereas in the common goldeneye it is confined to the margin of the feathers. At this date, too, the first white feathers come in betxveen the hill and the eye. These increase In number throughout the winter, whilst numbers of pure white feathers come on the chest until the brown of immaturity disappears. Thus the advance of plumage continues to lake place until March, when the young male has gained a considerable portion of its first spring dress, ~vhich is more or less similar to the adult male, except that the black and ~vhite scapulars are never fully attained, nor are the hind neck or flanks complete. The wings and tail still show the bird to be immature until the latter part of June or early July, when the usual complete moll takes place, the ~vhole of the bird going into a partial eclipse similar to the adult male. In September the eclipse is shed, and all traces of immaturity have disappeared, so that in the following month, or, more correctly speaking, November, the bird is adult, at about 16 months.

The same writer describes the semieclipse plumage of the male, as follows:

At the beginning of July the adult male undergoes a fairly complete change to an eclipse plumage, although the white feathers in front of the eye are never completely lost. In this month the head and neck become a somewhat dirty gray brown, very light in the throat; the flanks, hind neck, and upper mantle, also portion of the lower neck and chest are brown with gray edgings; mantle, scapulars, brown, with light brown or gray edgings or tips; the whole bird now resembles a somewhat dirty-looking female, but its sex can easily be recognized by its superior size, small white feathers on the head, and by the wings, which always remain the same, which, with the tail and part of the back and tail coverts, are only melted once in the season. The adult male has scarcely assumed its eclipse dress before it again commences to molt into winter plumage, and in the case of all these ducks the process of change at this season may be said to be practically continuous.

The female undergoes the same sequence of plumage to maturity as the female goldeneye, attaining full maturity at an age of about 15 months. The females of these two species are very difficult to distinguish at any age. Mr. Millais (1913) says:

The characters of the female Barrow’s goldeneye, apart from superior size, are the black back and tail, blackish head and longer crest, and general difference of a more intensified black and white. The yellow bill spot is also more extensive.

William Brewster (1909a) has made an exhaustive study of this subject, and I would refer the reader to his excellent paper on it. I would refer the reader also to a paper on this ‘subject by H. F. Witherby (1913) and a still more exhaustive treatise by Maj. Allan Brooks (1920).

Food: The food of the Barrow goldeneye seems to be the same as that of the common species. Dr. F. Henry Yorke (1899) records it as feeding on minnows and small fishes, slugs, snails, and mussels, frogs, and tadpoles, in the way of animal food; he has also found in its food considerable vegetable matter, such as teal moss, blue flag, duckweed, water plantain, pouchweed, water milfoil, water starwort, bladderwort, and pickerel weed. Mr. Munro (1918) says:

The feeding habits of the two species of goldeneye are identical. Both species are greatly attracted by the small crawfish lurking under large stones in shallow water. While hunting these shellfish, the (lucks work rapidly along the shore, diving~ every few minutes, to probe under the edges of the large stones. They invariably try to submerge even if the water is not deep enough to cover their backs, and I have never seen them dipping as redheads and scaups frequently do. One can follow the goldeneye’s movement as it encircles the large stones, by the commotion on the surface and by frequent glimpses of the duck’s back. In shallow water, the birds remain below from 15 to 20 seconds, the crawfish being brought to the surface to be swallowed. By the end of winter the feathers on the forehead are generally worn off, through much rubbing against stones in this manner of foraging. When feeding in deep water, over the beds of Potamogeton, they stay in the same place until satisfied. In such places the small snails and crustacea that attach themselves to the stems of Potarnogcton form their chief food, but little vegetable matter being taken beyond what is eaten with the shells. The small shellfish are swallowed while the birds are below the surface of the water, unlike the procedure followed with the larger crawfish. Their stay under water Is of fairly uniform duration, ranging from 50 to 55 seconds. At the beginning of the dive the tail is raised and spread to its full extent.

Behavior: He writes of its habits:

As far as I have been able to observe, there is no difference in the flight of the two species of goldeneye. Both have the same clumsy way of rising, and of flying cl,se to the surface before attaining any speed; once under way they travel swiftly, and one’s attention is held by the distinctive, musical whistle of their wings. Both the Barrow goldeneye and the American goldeneye are less gregarious than others of our ducks with the exception of the mergansers. I have never seen the Barrow goldeneye in large flocks except In the mating season. When feeding, two or three birds together are the rule, and five or six the maximum number noted.

Dr. D. G. Elliott (1898) writes of its behavior:

I have found it at times quite numerous on the St. Lawrence near Ogdens: burg, and have killed a goodly number there over decoys, and some specimens, procured on these occasions, are now in the Museum of Natural History in New York. The two species were associated together on the river, and I never knew which one would come to the decoys, but I do not remember that both never came together, unless it might be the females, for, as I have said, It was difficult to distinguish them without an examination.

The birds would fly up and down the river, doubtless coming from, and going to, Lake Erie,. stopping occasionally in the coves to feed, and floating down with the current for a considerable distance, when they would rise and fly upstream again. My decoys were always placed in some-cove or bend of the stream where the current was least strong, for I noticed the birds rarely settled on the water where it was running swiftly. This ducl~ decoys readily in such situations, and will come right in, and if permitted, settle among the wooden counterfeits. They sit lightly upon the water and rise at once without effort or much splashing. The flight is very rapid, and is accompanied with the same whistling of the wings so noticeable in the common goldeneye. In stormy weather this bird keeps close to the banks, seeking shelter from the winds. It dives as expertly as its relative, and frequently remains under water for a considerable time. The flesh of those killed upon the river was tender and of good flavor, fish evidently not having figured much as an article of their diet.

Maj. Allan Brooks writes that “the note is a hoarse croak. They have also a peculiar mewing cry, made oniy by the males in the mating season.”

Mr. Millais (1913), who studied this species extensively in Iceland, writes of its behavior there as follows:

On the water the male of this species looks a larger, clumsier, and blacker bird than the commou goldeneye. It seemed to me that it sits higher on the. water, and was a bird that commanded instant attention. In summer the males, which, when the ducks have begun to sit, consort in small parties of two to six, or more, are exceptionally tame, and will permit an approach to within a few paces, if the observer moves slowly to the banks of the river where they are feeding or resting. In rising to fly they are somewhat clumsy, and run along the surface with considerable splashing, hut they did not seem to me to make nearly so much noise in flight as the common species. The “singing” or “ringing” note is heard, but it is neither so load nor so metallic. On June 27 the males were still in their breeding dress. A few seem to keep on the river near the nesting females, as if for forms sake, but the majority were resorting to the great lake of Myvatn, where the parties seemed to increase in size day by day. Females, with young, often floated past nie while I was trout fishing, and once I had to draw in my line to prevent hooking a too confiding mother. Whilst watching males on feed, it struck me that they were less expert than the common gokleneye, and had more difficulty in getting under water. There was more noise and splash to get under, but once below the surface they seemed to be skilled performers of the highest order. I saw them more than once, from the high bank where my tent was pitched, feeding in exactly the same manner as the common species, turning over all the small stones, and probing beneath all large ones, and into holes. They stay less time under water in shallows than in the deep water of the lake, the time occupied being a half to one minute. On the river they reappeared again and again at the same spot, only pausing for a moment’s rest and splash down again, whereas on the lake they would often keep moving forward in their dives, and take up a fresh position every time. They will stay and fish In very rough streams, edging into the current and out again as soon as they rise, hut do not like such wild places as the harlequin.

In Iceland their enemies seem to be Richardson’s skua, Stercorarius paresiticus L., which regularly attacks the females of all diving ducks and seizes their young, and the Iceland falcon, Felco rasticolus islandicus, which kills a few of the adults. There was hardly a morning or evening when I stayed at Myvatn, in June-July, 1889, that we did not see one or other of these two species harrying the ducks. Sitting in the tent to escape the awful plague of flies, a sudden roar of startled ducks ~vould he heard, and on my going to investigate there was the falcon, with perhaps two young birds in attendance. bearing off some victims of its prowess. None of the ducks seemed to be unusually scared when the falcons passed by, as they often did, by day and night. They crouched on the water or rushed with their broods under the banks and hid as well as possible. It was only after the stoop and kill, ~vhen the bird of prey came on to their own level, that there was a general stampede of these ducks in the Immediate vicInity of the murder.

Mr. Lucien M. Turner, in his unpublished notes, says:

These goldeneyes are common along the entire coast of Labrador and occur in scattered flocks of two or three to rarely more than a dozen in number. I have never found the nest or eggs of this species and am not positive that it breeds on the coast; although it occurs during the summer season, arriving by the 1st of June, and remains until early November. During the latter part of its stay it frequents the places of swift tide currents xvhere it dives with wondrous celerity to procure its food from the bottom of soundings. Numbers of these birds were seen in a pocket some 2 miles from the mouth of the Koksoak River and on the left band. This place is locally known as Partridge’s fishing place. I was camped there while delayed by stormy weather, and early each morning great numbers of these birds frequented the inner portion of the cove. Strange to say, these birds never made the same noise with their wings when they flew into the cove that they did when they flew out. The tempestuous weather and great distance prevented me from securing any specimens in that locality. This was late in September, and these birds congregated in large numbers, for some of the flocks certainly contained 200 individuals and were doubtless preparing to journey to the southward. None were seen after the last of September. I observe that these ducks are nocturnal in their habits and especially noisy toward the approach of day. They search for fresh feeding grounds from daylight to sunrise and appear to be very quiet, unless disturbed, during the midday hours.

Mr. Skinner says, in his notes:

I usually find these ducks by ones and twos and small groups, but once I found a flock of 85 swimming in a compact group off the shore of Yellowstone Lake. When in pairs, it Is the female that takes alarm and flushes first. They take great delight in “shooting the rapids ‘; nothing in the Gardiner River, at least, being too rough for them. They drop down over a fall 3 feet high, and at the bottom go out of sight in the foam and spray, but nevertheless keep right on swimming along. Should they tire of this boisterous sport, they are quick to take advantage of any eddy, or rest behind a bowider. As a rule these are the tamest of our ducks; on the reservoir and other roadside waters they are unalarmed even while the big autos go thundering past. If I approach a flock too closely, the Barro~vs s;vim away, or go coasting down the rapids, Instead of flushing as the mallards do. But if they do flush, they go only a little way, come back, and drop down again into the water without hesitation. or fear.

I do not believe the Barrows seek the society of other ducks, but common tastes bring them to many other ducks, mostly deep-water ducks, such as mallards, mergansers, butlieheads, ruddy ducks, bluebilis, and American goldeneyes. Sometimes the last named and the Barrows are together, but more often the t~vo species keep apart, possibly due to the rivalry of the males.

Flight is low and labored at first, as they rise against the wind, and they are often compelled to kick the water for the first 20 or more wing strokes. I have seen them start and later strike the xvater again where the average pitch of the rapids was 6 per cent or less. Rising against a strong head wind, they do much better, and then they may fly at a greater height titan in calm weather, say of 30 or 40 feet. Once I was passing up a narrow stream with the wind behind me when I found a half dozen Barroxvs before me. They could not fly up into my face and the canyon xvas too high and narrow to fly out sideways, so the ducks were obliged to swim down past me and rise behind my back. Apparently they can not jump up as the mallard does so frequently. But once under way. flight is s~vift and powerful. giving rise to a distinct whistling sound.

These ducks bathe by standing almost erect on the water and rapidly flapping their wings so as to thro~v the water forward and over them ; later by plunging under and shaking themselves at the same time. They usually dress their feathers while on the water, turning far over, first on one side, then on the other, to get at places ordinarily under the surface. Once I found a Barrow preening on a half submerged bowider.

Winter: The winter home of the Barrow goldeneye is not far south of its summer range, and its migration is not much more than a movement off its nesting grounds to more satisfactory feeding grounds. It seems to be fairly common on the Gulf of St. Lawrence in winter, where it frequents about the same resorts as the common goldeneye, but farther south on the Atlantic coast it is rare. It winters on some of the large lakes and rivers of the interior, as well as on the Pacific coast.

J. A. Munro (1918) says that “throughout the winter months it is found on the seacoast, in the many sheltered estuaries from Puget Sound to Hecate Strait and Dixon Inlet.” He also writes to me “that a few birds winter on the Okanogan River below Okanogan Falls in a rapid stretch of water with strong bottom, where crawfish are very abundant. They are usually in company with the common goldeneye.”

Mr. Skinner writes to me:

While the majority migrate on the freezing of the waters, a few remain along the Gardiner and Yellowstone Rivers all winter, and become even tamer than usual, entitling them to be rated as resident (in Montana) at all seasons. Barrows that had wintered along the Gardiner in 1920: 21 began leaving about February 25, or about the time that waters elsewhere were beginning to open. First to go were the males, then the females and immatures; until only one was left on March 1, and that one went next day. But cold, freezing temperature brought them back, a female on the 7th and six drakes and five females on the 12th; then they decreased again. By the 24th they were abundant at the outlet of Yellowstone Lake at 1,000 feet higher altitude or just over 7,700 feet above sea level.

DISTRIBUTION

Breeding range: In North America, a few breed on the Labrador Peninsula from the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Point des Monts) to northern Labrador (Davis Inlet). But the main breeding range is in the vicinity of the Rocky Mountains. East to western Alberta (Banif), northwestern Montana (Glacier National Park) and central northern Colorado (Boulder County). South to southwestern Colorado (Dolores County). West to southwestern Oregon (Crook County and Douglas County), central British Columbia (Okanogan and La Hache Valleys), to the coast of southern Alaska (Chilkat and Sitka), and south central Alaska (Lake Clark). North to northern Mackenzie (Fort Anderson rarely) and Great Slave Lake (Fort Rae and Providence). Breeds abundantly in Iceland and in Greenland up to 69~ or 70~ N.

Winter range: From the Gulf of St. Lawrence southward along the coast regularly to eastern Maine (Washington County), rarely to southern New England and as a straggler beyond. On the Pacific coast from southern Alaska (‘Wrangell and Portage Bay) to central California (San Francisco Bay). Rarely and irregularly in the interior, south to southern Colorado (La Plata River), and north to southern British Columbia (Okanogan Lake) and northern Montana (Great Falls).

Spring migration: Dates of arrival: Quebec City. April 14 to 16; Mackenzie, Fort Anderson, June 14. Late dates: Ontario, Toronto, April 18, 1885; North Carolina, near Asheville, May 6, 1893.

Fall migration: Dates of arrival: Quebec, Montreal, October 23; Connecticut, East Haven. November 14; Massachusetts, Wareham, November 27; District of Columbia, November 22, 1889; Wisconsin, Lake Koshkonong, November 14, 1896.

Casual records: All records east of the Rocky Mountain region and south of New England must be regarded as casual. Most of these records are based on females, incorrectly identified. The records given above, under migrations, are believed to be authentic, as are also the following: Michigan, Ottawa County, 1907, and Detroit River, April 1, 1905.

Egg dates: Iceland: Fourteen records, May 19 to June 30; seven records, June 2 to 17. British Columbia: Five records, May 12 to 31. Alberta: Two records, May 28 and 30.