With a relatively small breeding range in northwestern Alaska, the Western Sandpiper is nonetheless abundant, with millions of birds making annual migrations each year. Male Western Sandpipers usually return to the same breeding territory each year.

Red foxes and jaegers are the main threats to the nests of Western Sandpipers. When the chicks hatch from successful nests, they accompany the adults for a few weeks until they can fly, at which time they are abandoned.

On this page

Description of the Western Sandpiper

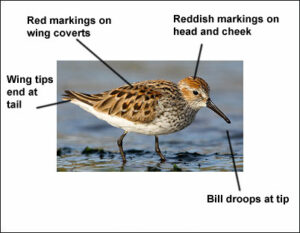

BREEDING MALE

The Western Sandpiper is a small shorebird with dark legs and a relatively long, down-curved, dark bill. Breeding birds are heavily spotted below, and have reddish scapulars and reddish above and behind the eye. In flight, a white wing stripe is visible. Length: 6 in. Wingspan: 14 in

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

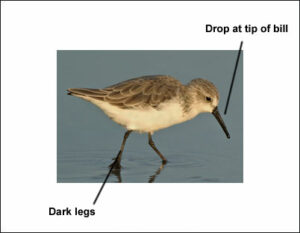

Winter birds are plainer, with white underparts and gray upperparts.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to breeding adults, but have grayish wing coverts with pale edges.

Habitat

Western Sandpipers inhabit mudflats, shorelines, beaches, and tundra.

Diet

Western Sandpipers eat insects, mollusks, and crustaceans.

Behavior

Western Sandpipers forage in shallow water or in mud.

Range

Western Sandpipers breed in northern Alaska. They winter in South America, and occur across western portions of the U.S. in migration. The population is stable.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Western Sandpiper.

Fun Facts

Western Sandpipers migrate from Alaska to southern South America each year, primarily in the west, but regularly in the east in smaller numbers.

Female Western Sandpipers often leave the young with the male a few days after they hatch.

Vocalizations

The flight song is a weak trill. A “cheet” flight call is also given.

Similar Species

- Semipalmated Sandpipers have shorter bills.

- White-rumped and Baird’s Sandpipers have wing which are longer than the tail when folded.

Least Sandpipers have yellowish legs.

Nesting

The Western Sandpiper’s nest is a depression lined with lichens and leaves, and is placed under a shrub or under grass.

Number: Usually lay 4 eggs.

Color: Whitish with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 21 days, and leave the nest shortly after hatching, though associating with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Western Sandpiper

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Western Sandpiper – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

EREUNETES MAURI Cabanis

Spring: The western sandpiper has an unique distribution and peculiar migrations. It occupies a very restricted breeding range in the coastal regions of northwestern Alaska, but is spread out over a wide winter range, entirely across the continent in southern North America, in Central America, and in northern South America. But we know very little about its migration routes between these two seasonal ranges. I have not a single spring record for it from any of my correspondents in the interior. Undoubtedly it has been generally overlooked on account of its close resemblance to the semipalmated sandpiper, an abundant species which few collectors bother to shoot. Its northward migration along the Pacific coast, in April and May, is well known; this flight is mainly coastwise and the birds are often extremely abundant. D. E. Brown, in some notes sent to me from Westport, Washington, refers to this species as easily outnumbering all other shorebirds combined; they were associated with red-backs, but outnumbered them 10 to 1. Dr. E. W. Nelson (1887) says of the arrival of these birds in Alaska:

As the snow disappears on the low ground about Norton Sound, from the 10th to the 15th of May each year, and the ponds, still ice-covered, are bordered by a ring of water, these gentle birds arrive on the shore of Bering Sea, in the vicinity of Saint Michael and the Yukon mouth. The advancing season finds their numbers continually augmented until, toward the end of May, they are extremely common and are found scattered everywhere over the mossy fiats and low hillsides. Their gentle character and trusting ways render them very attractive to the frequenter of their territory at this season.

Courtship: The same gifted writer describes the courtship of this gentle little sandpiper as follows:

The warm days toward the end of May cause the brown slopes and flats to assume a shade of green, and among the pretty bird romances going on under our eyes none Is more charming than the courtship of this delicate sandpiper. They have forsaken the borders of icy pools, and, in twos and threes, are found scattered over the tundra, showing a preference for small dry knolls and the drier tussock-covered parts of the country In the vicinity of damp spots and small ponds. Here the gentle birds may be seen at all times tripping daintily over the moss or in and out among the tufts of grass, conversing with each other in low, pleasant, twittering notes, and never showing any sign of the wrangling so frequent with their kind at this season. The female modestly avoids the male as he pays his homage, running back and forth before her as though anxious to exhibit his tiny form to the best advantage. At times his heart boats high with pride and he trails his wings, elevates and partly spreads his tail, and struts In front of his lady fair In all the pompous vanity of a pigmy turkey-cock; or his blood courses in a fiery stream until, filled with ecstatic joy, the sanguine lover springs from the earth, and, rising upon vibrating wings, some 10 or 15 yards, he poises, hovering in the same position, sometimes nearly a minute, while he pours forth a rapid, uniform series of rather musical trills, which vary in strength as they gradually rise and fall, producing pleasant cadences. The wings of the songster meanwhile vibrate with such rapid motion that they appear to keep time with the rapidly trilling notes, which can only he likened to the running down of a small spring and may be represented by the syllables tzr-r-e-e-e, zr-e-c-e-, zr-e-e-e, in a- fine high-pitched tone, with an impetus at each “z.” This part of the song ended, the bird raises its wings above its back, thus forming a V, and glides slowly to the ground, uttering at the same time, in a trill, but with a deeper and richer tone, a series of notes which may be likened to the syllables tzur-r-r-r, tzar-r-r-r. The word “throaty~~ may be applied to these latter notes as distinguished from the high-pitched key of the first part of the song.

Nesting: Herbert W. Brandt, who has had extensive experience with the nesting habits of this species, says in his manuscript notes:

The gentle little western sandpiper is the most abundant and most widely distributed shore bird occurring in the Hooper Bay region. Throughout the area, wherever dry ground is found, it is plentiful, and It even occurs on the lower mountain slopes of the Askinuk Range. Before the tundra had discarded its snowy mantle the first birds of this species had responded to the lure of early spring, for they arrived on May 14, and two days later they were common, while on May 20 they were abundant, carrying on everywhere their dainty aerial butterfly courtship. The western sandpiper is usually found in large scattering colonies especially on the upland tundra where for large areas they average one or two pairs to the acre. Isolated couples, however, are occasionally encountered.

The nest of the western sandpiper is well concealed from view by the surrounding curly bunch-grass that everywhere In the dryer areas forces its way up amid the moss. Under this protection a depression is made and scantily lined with grass, and usually in addition with considerable tiny leaves of the prostrate berry-bearing vines, of the dwarf birch, and of the reindeer moss stems. In consequence, the nest is very fragile and loosely made, but before it is disturbed it is neatly cup-shaped. The range of measurements of 32 nests is: Inside diameter, 2 to 3 inches; depth of cavity, 1% to 3 inches; and total depth, 2 1/2 to 4 inches. Both male and female share in the tender duties of incubation and are often very loath to forsake their nest, so that when crossing their chosen haunts an incubating bird, by fluttering up before one’s very feet, will occasionally unwittingly betray its well-concealed abode.

Those charming little creatures are most brave, even eager in defense of their homes, often charging with puffed-out feathers and head drawn against the body to make themselves look as formidable as possible. Their tameness and familiarity are remarkable. Often after we had removed the eggs the parent would go to the empty nest, sit on it for a little while, then come out, her little body a-purr with agitation, and inquire in her thin incessant voice what had become of the eggs. It is little wonder that I shot very few specimens for identification purposes. This tiny sandpiper had won too deep a place In my affections.

The confiding nature of these birds is referred to by other writers. Doctor Nelson (1887) tells how one of his men lay on the ground with his outstretched hand close beside a nest; but the bird soon returned, crossed his arm and settled on the nest, where she was caught with turn of his hand and released. Alfred M. Bailey (1926) placed his “hat over one set of eggs, having just room for the parent bird to crawl tinder, which she immediately proceeded to do.”

Eggs: Herbert IV. Brandt has given me the following good description of his 120 eggs of this species, collected by him at Hooper Bay, Alaska:

Four eggs always constitute a complete set with the western sandpiper, but occasionally late nests with three eggs in each were observed, which were probably second layings. They are pyriform to subpyriform in shape and are placed in the nest with the small ends together and pointed downward, snuggling amid the loose interior contents of the nest. The shell is smooth, has a slight luster, and is strongly constructed. The markings on the same set of eggs always follow the same type in color, and likewise the round color is always the same shade. In the series of eggs the prevalent round color is “cream color,” but the shades vary from dull white, which is very rare, to equally rare “wood brown.” The ground color Is often almost obliterated by the profuseness of the markings, especially on the larger two-thirds of the egg. The color of the surface markings is usually “Kaiser brown,” but they show considerable variation, dependent upon the amount of pigment deposited, ranging from “brick red” to “chestnut brown.” The spots are somewhat elongated and vary from small pin points to large blotches that may completely cover the larger end of the egg. These have a decided tendency to spiral from left to fight. The underlying markings are inconspicuous and are only visible on eggs having a pale background and then they are of small size and indistinct. The eggs are generally flecked with additional markings consisting of a few intense irregular spots or fine lines of slate black to black. These blackbird like markings are almost always on the larger end, although on many eggs they are entirely wanting. In series the eggs of the western sandpiper have a decidedly bright red appearance, and are thus distinct from any eggs occurring in the Hooper Hay region.

The western sandpiper has been known to lay five eggs.

The measurements of 120 eggs, furnished by Mr. Brandt, average 30.8 by 21.9 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 32.5 by 22.3, 32 by 22.8, 28.7 by 21.6, and 30.3 by 21.1 millimeters..

Young: H. B. Conover tells me that both sexes incubate, at least both had incubation patches. He says in his notes:

On June 15 the first newly hatched young were found. The parents were very solicitous and flew about twittering anxiously. Soon other old birds joined them and seemed just as anxious as if the young were their own. This habit of these sandpipers In joining forces to help their neighbors was very noticeable both before and after the eggs had hatched. By June 30 halfgrown young that could already fly for a few yards were being seen. Western snndpipers with their chicks were everywhere, and during a walk around the tundra you had a constant attendance of anxious mothers and fathers wheeling about. Eggs were still being found on July 5. By July 18 the mud flats were covered with fully fledged young of this species.

The incubation period for this species seems to be about 21 days. A nest found on May 26 with four eggs hatched on June 15 late In the evening. Another found on May 29 with three eggs in It, had four eggs on May 30, and three young and a pipped egg on the evening of June 19. The rapidity with which these birds lay and hatch their eggs and raise their young is very remarkable. In 60 days from their arrival on the nesting rounds the young are full grown and taking care of themselves.

Mr. Brandt in his manuscript says:

It seemed to us as if every western sandpiper about Hooper Bay must have deposited its first egg on practically the same day, because the four days following May 26 more than 50 nests were recorded, and after June 15 the beautiful brown and black mottled young all of the same size were to be found everywhere. These newly born bird mites are not long abed, however, for in one case an hour after hatching their cradle was empty.

Plumages: The downy young western sandpiper, when first hatched, is richly colored in warm, bright browns and buffs, quite different in appearance from the young semipalmated sandpiper. Behind a broad “cinnamon buff” forehead is a large, rounded crown patch extending from above the eyes to the nape, in which the down is basally black, but deeply tipped “burnt sienna”; in the center of this a cluster of buffy down tips produces a spot, which is divided by a blackish median stripe extending down to the bill; a band of pale buff, produced by down tips, encircles the sides and rear of the crown patch; there is a loral stripe and a short malar stripe of black; the sides of the head and neck are “cinnamon buff”; and a variable pattern of “burnt sienna” decorates the auricular region, behind and above the eye. The remainder of the upper parts, back, wings, rump, and thighs are a mixture of black and dark, rich browns, “bay,” “burnt sienna,” and “amber brown,” sprinkled, in an irregular pattern, in the darker portions with tiny buff tips. The under parts vary from pale buff on the breast to buffy white on the throat and to white on the belly. The bright colors fade to dull browns and grayish as the chick grows older. The first of the juvenal plumage appears on the scapulars and then on the sides of the breast.

In fresh juvenal plumage, as seen in Alaska in June, the crown is “sepia~~ with “pinkish cinnamon” edgings; the nape is “drabgray,” streaked with dusky; the feathers of the mantle are brownish black, edged with “tawny” on the back and broadly edged with “tawny” and white on the scapulars; the rump, upper tail coverts, and central tail feathers are “sepia”; the other rectrices are “light mouse gray ~ the wing coverts are ” mouse gray,” tipped with “tawny” or lighter buff; the throat and under parts are white, washed on the breast with “light cinnamon-drab,” and streaked on the sides of the breast with dusky. This plumage fades somewhat during migration and the body plumage is mostly all molted before October. In their first winter plumage young birds can be distinguished from adults only by the wing coverts and a few retained scapulars and tertials. At the first prenuptial molt they become practically adult.

Adults have a complete postnuptial molt in the summer and fall, molting the body plumage in July and August and the wings and tail in November or later. The prenuptial molt in March and April involves only the body plumage. The fresh plumage, in April, is veiled with “drab-gray” tips, which soon wear away, revealing the bright nuptial colors.

Food: Very little has been published on the food of the western sandpiper, but it probably feeds on the same things as the others small sandpipers with which it associates. Arthur H. Howell (1924) says:

Six stomachs of this bird collected in Alabama showed its food to be minute fly larvae, aquatic beetles and bugs, marine worms, and small snails.

Stuart T. Danforth (1925) found 150 bloodworms and a Hydrophilid larva in the stomach of one taken in Porto Rico.

Behavior: S. F. Rathbun has sent me the following notes on the habits of the western sandpiper on the coast of Washington:

This is one of the small sandpipers of this region that will be found common at the time of the migration poriods along the ocean beaches and on the tide fiats. It occurs in flocks of varying sizes, soule of which contain an exceedingly large number of birds. At times if care is used one can approach a flock quite closely, often within 15 or 20 feet, and it is of interest to watch the actions of the individuals. They are active birds, being constantly on the move as they feed, and while thus engaged keep up a continual conversation, as it were, this being of the nature of a soft, roiling whistle which Is olensant to hear. These sandpipers seem to prefer to feed at or near the waters edge, partIcularly where there is an ebb and flow, being very active in following up the water as It recedes and equally so in avoiding its incoming, but always at the very edge as it were. They secure their food by a skimming like movement of the bill over the surface of the mud thnt has just been covered by the water, and as the birds advance or retreat in following the flow it is quite amusing to observe the seeming pains taken to avoid coming into contact with it. And still at times individuals may be seen in some of the very shallow spots. It Is a fine sight to see a flock of these sandpiper suddenly take alarm as they are feeding; all quickly spring into the air as if moved by the same impulse at exactly the same moment, and then form a compact body that will execute a variety of evolutions in perfect harmony. The flock will rise and fail and wheel and turn, and at times may split into several smaller ones, these to again reunite, and should one happen to stand where the light falls directly on the birds the white of their underparts as they turn is very striking. These actions may be repeated a number of times, and then without warning the flock of birds ivill alight and quickly scatter in senreb of food. Scenes like this are what give an enlightenment to the waste places and fortunately, under the protection now afforded the species, are likely to continue to be enacted in the future. But large as the numbers of the western sandpiper still appear to be, they are not comparable to thoso of fifteen or twenty years ago, and the cause of this decrease in their numbers is the same old story. It seems hardly possible that a bird so small could have boon regarded as game and its hunting come under the name of sport, but such ~vas the case and It brought about the logical result. One may be thankful, however, that this no longer can be done, and hope that the lapse of time may bring about somewhat of an increase in the number of these birds.

Voice: John T Nichols contributes the following on the calls of this species:

The most common loud call of the western sandpiper has the cc sound found in the hi-cop of the least sandpiper, a plaintive quality as in the voice of the sanderling, and suggests somewhat the squawk of a young robin. It is variable and may he written chce-rp, cheep, or cftfr-cep. It seems to be the flight note of the species, corresponding to the cherk of the semipalmated sandpiper, and is also used by a bird on the ground calling to others in the air which alight with it, as such flight notes sometimes are. Its closest resemblance with a note of the senaipalmated is to the scrap sometimes heard from that bird when flushing.

Some of the calls of the western are apparently indistinguishable from those of the semipalmated sandpiper, but as studied on the northwest coast of Florida, where it greatly outnumbered the other form, more seemed different. Birds took wing with a sirp, or at another time a chir-ir-ip, which heard also in a medley of variations from a flock already on the wing, suggesting the notes of the horned lark, may be more or less analogous with the short flocking note of the semipalmated sandpiper.

Field marks: It is most difficult and often impossible to distinguish between the western and the semipalmated sandpipers in life; and I have experienced difficulty in distinguishing between them even in the hand. The western has a longer bill, and I believe that the bill measurements of corresponding sexes do not overlap, though they approach very closely; but the longest-billed female semipalmated may have a longer bill than the shortest-billed male western. In spring and summer plumages the xvestern shows much more rufous in the upper parts and is more conspicuously and more heavily streaked on the breast, but in winter plumage the two species are very much alike. Mr. Nichols has given me a few characters by which this species can be recognized even in winter; he calls it “a somewhat larger, rangier, paler, grayer bird” than the semipalmated; it also has “better developed white stripes over the eyes which meet more broadly on the forehead, the top of the head is not so dark, its dark auricular area is not so prominent, the markings on the top, and particularly on the sides, of the head and neck are finer.

As to the bills, he says:

There is a subtle difference In their bills, however, which I have frequently noticed in life and once or twice checked by taking specimens. The bill of a long-billed semipalmated sandpiper is quite straight and becomes slender townrd the end; that of a short-billed western Is not so slender toward the end and with just an appreciable do~vnward bend before its tip. In longhilled individuals of the western sandpiper the bill becomes slender toward the end and frequently has a decided drop at the tip. Such birds are unmistakably ,lifferent to anyone thoroughly familiar with the semipalniated sandpiper.

Fall: Like many other waders, these little sandpipers begin to move off their brecdina grounds at a very early date. As early as June 21, 1914, F. S. Hersey saw western sandpipers flocking at the mouth of the Yukon River, Alaska. Some of the flocks contained from 40 to 60 birds. The larger flocks were all of this species, but the smaller flocks often contained one long-billed dowitcher.

Doctor Nelson (1887) says, of its fall wanderings:

Early in July the young are on the wing and begin to gather In flocks toward the 1st of August. The last of these birds are seen on the coast of Norton Sound and the Yukon mouth the 1st of October. Although it Is not recorded from the Seal and Aleutian Islands, I have seen the bird at St. Lawrence Island, south of Bering Straits, and at several points along the northeastern coast of Siberia, and it frequents the Arctic coasts of Alaska In addition to being found throughout the interior along streams where suitable flats occur. Murcioch notes it as a fall visitor at Point Barrow. It has been found In abundance on the southeast coast of the Territory, where it occurs during the migrations.

On the coast of British Columbia and farther south it is an abundant fall migrant, but it is rare or casual inland; the first arrivals sometimes reach California before the middle of July. Migration records for the great interior are almost entirely lacking and how it reaches the Atlantic coast, where it is so abundant in fall and winter, is a mystery.

Mr. Nichols wrote to me as follows:

The occurrence of this bird on the North Atlantic coast of the United States is Irregular. At times It Is really numerous on Long Island over periods of several years, and then It becomes rare again. In the 1912 southward migration the western was carefully looked for among the abundant semipalmated sandpiper but no evidence of its presence was found. In 1913 a single bird with a very white head and a peculiar note suggesting a young robin was, I now feel confident, a western sandpiper, at the time it passed as unidentified. The following year one of the white-headed long-billed juvenal westerns was picked out in a flock of semipalmated in August and collected. Later several others, all well-marked birds were identified in flocks of the semipalmated. In 1916 and 1917 the species was still more numerous. On October 12, 1917, at Long Beach with 11. 0. Murphy it was estlmkted that about one-half the Th-eunetes were this, one-half the common eastern form. Specimens of each were obtained from gunners present. The following year (1918) a flock on the beach In late spring (lnne 2) were predominatingly western; the specIes returned again from the north In early July (July 4). During this or the immediately succeeding southward migrations the semipalmated fell off In numbers, and furthermore, a great many birds thought to be western were Indeterminate. Mr. B. P. BIcknell met the same condition which I found at Mastic further ~vest at Long Beach. I remember a letter wherein he spoke of the semipalmated being replaced by the western, but I did not take just that view of It. For a year or two I have no real Idea how common either species ~vas. I saw numerous birds that seemed to he western, but mostly indeterminate, and took no specimens. Later the standard semipalmated reestablished Its usually large numbers and this season (1925) probably for the first time the western was again common among them, about as In 1916, some of this latter form easily identifiable birds (in life).

Winter: Arthur T. Wayne (1910) says:

The western sandpiper is the most abundant of all the waders that winter on this coast. It is not unusual to see thousands of these birds any day during the winter months. It can almost be considered a permanent resident, as it is only absent from May 20 until July 8. The adults arrive in worn breeding plumage and Immediately begin to moult the feathers of the head and throat. By the first week In August they have acquired their autumn plumage.

Among the big flocks of small sandpipers that we saw’ all winter frequenting the extensive mud fiats in the vicinity of Tampa Bay, Florida, I am satisfied that this species was well represented, if not the predominating species. I confess that I can not identify in life more than a very small percentage of these little “peep,” and then only when seen under most favorable circumstances. One dislikes to shoot any number of the gentle little birds for identification. But what few we shot proved to be western sandpipers, and I am inclined to think that. most of them were. Mr. Nichols writes to me:

In my limited experience ma~uri is commoner than ljusiflus on the west coast of Florida. In Wakulla County In March and September, 1919, most all the Ereunetes were western, only one or two among them definitely identified as pueUlus; and in April, 1917. two or three western were identified with least -sandplpers south of Sanibel Light.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: North America, Central America, the West Indies, and northern South America.

Breeding range: So far as known, the western sandpiper breeds only in Alaska. North to Cape Prince of Wales, Cape Blossom, Point Barrow, and Camden Bay. East to Camden Bay and St. Michael. South to St. Michael, Pastolik, and looper Bay. ‘West to Hooper Bay, Nome, and Cape Prince of Wales. It has been taken in summer in northeastern Siberia at two points, East Cape on July 14, 1913, and Cape Serdze, on July 16, 1913.

Winter range: The Pacific, Gulf, and South Atlantic coasts of the United States, the lATest Indies, Central America, and northern South America. North to Washington (Dungeness Spit, and Smith Island); Texas (Brownsville and Corpus Christi); Louisiana (Cameron and Vermilion Parishes) ; Alabama (Dauphin Island); and rarely, North Carolina (Pea Island). East to rarely, North Carolina (Pea Island and Fort Macon) ; South Carolina (Charleston) ; Georgia (Blackbeard Island) ; Florida (Amelia Island, and Fort Myers); Cuba (Guantanamo); and Trinidad. South to Trinidad; Venezuela (Margarita Island) ; probably northern Colombia (Sabanilla); probably Costa Rica (Barranca Puntarenas); Tehuantepec (Tehuantepec City); and Lower California (La Paz). West to Lower California (La Paz) ; California (San Diego County, Alameda, Oakland, and Berkeley); and Washington (Point Chehalis, Seattle, and Dungeness Spit). It. also has been detected in winter on San Clemente Island, off the coast of southern California.

Spring migration: The spring movement of birds that have wintered on the South Atlantic coast is imperfectly known, there being available no interior records that indicate the route by which they reach the breeding grounds. The species has been detected at Long Beach, New York, as early as April 25, and at Mastic, New York, on May 12, while late spring departures from South Carolina have been noted at Charleston on May 8, and from Mastic, New York, on June 2.

Early dates of arrival in the West are: Arizona, Fort Verde, April 11, and San Pedro River, April 17; Colorado, Denver, May 2, and Loveland, May 9; Nevada, Smoky Creek, May 6; Idaho, Meridian, May 6; British Columbia, Sumas, April 20, and Chilliwack, April 26; and Alaska, Kuiu Island, April 28, Craig, May 2, Patterson’s Bay, May 7, Admiralty Island, May 8, Fort Kenai, May 12, Hooper Bay, May 14, and Prince of Wales Island, May 15.

Late dates of spring departure at western points are: Texas, Somerest, May 5, San Angelo, May 6, Seadrift, May 8, and Tom Green and Concho Counties, May 12; Kansas, Lawrence, May 26; South Dakota, Vermilion, May 24, and Forestburg, May 26; lower California, San Quentin Bay,, May 10; California, Fresno, May 12, Santa Barbara, May 16, Los Angeles, May 19, Alameda, May 21, and Owens Lake, June 1; Oregon, Mercer, May 14; Washington, llwaco, May 18, Neah Bay, May 24, Clallam Bay, May 25, and Quillayute Needles, May 30.

Fall migration: Early dates of arrival in the fall are: British Columbia, Courtenay, July 7, Nootka Sound, July 23, and Okanagan Landing, July 28; Washington, Cape Flattery, July 2, Destruction Island, July 3, and Granville, July 4; Oregon, Cow Creek Lake, July 4; California, Santa Barbara, July 3, Fresno, July 5, and Tulare Lake, July 7; Lower California, San Quentin, August 24; Mexico, San Mateo, August 7; Idaho, Meridian, July 23, and Big Lost River, July 25; Wyoming, Fort Bridger, July 13; Oklahoma, Old Greer County, July 19; Arizona, Tucson, August 16, and San Bernardino Ranch, August 24; Texas, Mobeetie, July 27, Beaumont, August 5, Rockport, August 12, Hereford, August 18, and Padre Island, August 21; Massachusetts, Monomoy Island, July 19, and Nahant, August 4; New York, Mastic, July 4, and Freeport, July 16; South Carolina, Charleston, July 8; and Florida, James Island, July 20.

Late dates of fall departure are: Alaska, Craig, September 24, and St. Lazaria Island, September 29; British Columbia, Chilliwack, September 11, and Comox, September 26; Montana, Great Falls, September 4; New Mexico, Albuquerque, October 5; Massachusetts, North Truro, September 2, and Harvard, September 8; New York, Chateaugay, September 13, Amityville, September 17, and Long Beach, October 12; New Jersey, Cape May County, September 14; District of Columbia, Anacostia River, September 25; and Virginia, Four-mile Run, September 11.

Casual records: Casual occurrences of the western sandpiper must, of course, be based upon specimen evidence, as this species is easily confused with the semipalmated sandpiper. For this reason several records are considered doubtful, while in other regions it may be more numerous than is now known. One was taken August 21. 1907, at Beaver, Pennsylvania, while two were collected at Burlington, Iowa, on October 15, 1895, and one at Columbus, Ohio, on September 12, 1925.

Egg dates: Alaska: 159 records, May 23 to July 7: 80 records, May 29 to June 15.