The Bronzed Cowbird has expanded its range northward during the past century. A slightly larger relative of the Brown-headed Cowbird, the Bronzed Cowbird typically chooses slightly larger host species to parasitize, for it too does not build a nest but instead lays its eggs in the nests of other birds.

Sometimes several female Bronzed Cowbirds will gather near the nest of a host species, and some or all of them may end up laying eggs in the same nest. A few species can recognize and reject cowbird eggs, but many don’t seem to notice and raise the young as if they were their own.

On this page

Description of the Bronzed Cowbird

BREEDING MALE

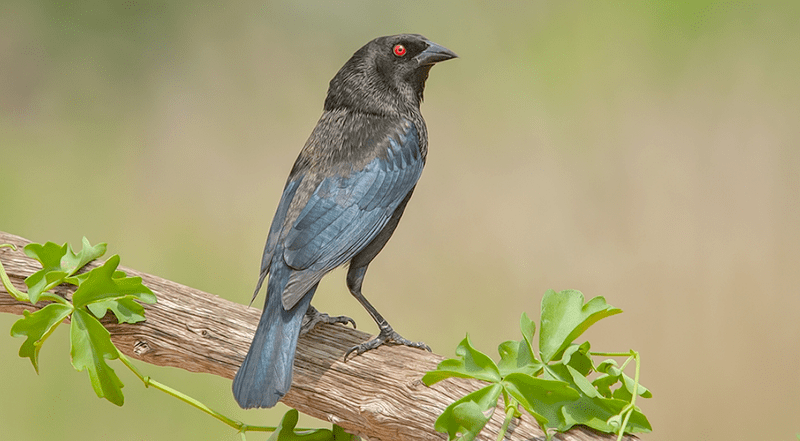

The Bronzed Cowbird is a mostly dark blackbird with a thick bill and curved upper mandible. Adults have red eyes.

Males have mostly black plumage with glossy bluish wings. A thick ruff of feathers on the neck creates a humpbacked appearance. Length: 9 in. Wingspan: 14 in.

Female

Eastern females are fairly uniform brownish-black in color. Western females are a much paler grayish-brown color.

Seasonal change in appearance

None.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to winter females, but are faintly streaked below.

Habitat

Bronzed Cowbirds inhabit open country, feedlots, and brushy areas.

Previously known as the Red-eyed Cowbird. Photograph © Alan Wilson.

Diet

Bronzed Cowbirds eat insects and seeds.

Behavior

Bronzed Cowbirds forage on the ground in open areas.

Range

Bronzed Cowbirds breed in the southwestern U.S. They winter in Mexico. The population is stable after a large expansion decades ago.

Fun Facts

Two U.S. subspecies account for the plumage differences in eastern and western birds; two additional subspecies do not occur in the U.S.

Bronzed Cowbird parasitism has impacted Hooded Oriole populations in Texas.

Vocalizations

The song consists of a soft whistle bracketed by gurgles. Whistle or rattle calls are given as well.

Similar Species

Brown-headed Cowbird

Brown-headed Cowbirds have dark eyes.

Shiny Cowbirds have thinner bills and are smaller overall. Typically found only along southern coastal Florida.

Nesting

The Bronzed Cowbird builds no nest, instead laying its eggs in the nests of other birds.

Bronzed Cowbirds can lay dozens of eggs over the course of a breeding season. They are pale blue-green in color.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 10-13 days, and fledge at about 11 days, though remaining dependent on the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Bronzed Cowbird

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Bronzed Cowbird – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

Miller’s Bronzed Cowbird

TANGAVIUS AENEUS MILLERI van RossemHABITS

This western race of the bronze-backed, red-eyed cowbirds is found in northwestern Mexico, from the Territory of Tepic on the south through Sinaloa and Sonora and into southern Arizona, breeding as far north as Tucson, Sacaton and the valley of the San Pedro River, where I collected a specimen near Fairbank.

Members of this race are slightly larger than those of the eastern race, with a stouter bill. The adult male is hardly distinguishable, except that the rump is violet, like the upper tail coverts, rather than bronzy like the back. The adult female is paler, dark mouse gray above, rather than dull black, and paler mouse gray below, rather than dark sooty brownish, as in the eastern race.

Nesting: Friedmann (1929) lists the following seven species as hosts of the bronzed cowbird; Derby flycatcher, Audubon’s oriole, Arizona hooded oriole, Selater’s oriole, canyon towhee, yellow-throated sparrow and Guatemala mockingbird. In later papers (1931, 1933 and 1938) he adds western white-winged dove, western kingbird, Giraud’s flycatcher, Cooper’s tanager, Griscom’s tanager, Xantus’s becard, scarlet-headed oriole, and Durango wren.

M. French Gilman (1914) shows a photograph of a hooded oriole’s nest containing two eggs of the bronzed cowbird and four eggs of the dwarf cowbird, also another that held two eggs of the bronzed cowbird and two of the oriole, both found near Sacaton, Ariz.

Herbert; Brandt tells me that he examined a nest of this oriole in Sabino Canyon, Ariz., that held one egg of the oriole and six eggs of the bronzed cowbird.

George N. Lawrence (1874) quotes Col. A. J. Grayson as follows:

On the 19th of May, 1868, whilst hunting in the woods near Magatlan, I discovered a nest of the Bull-head Fly-catcher (Pitangus derbianus), which is a common species in this region, and builds a large nest, dome-shaped, the entrance being on the side. Whilst I was quietly looking at the nest (which was about forty feet from the ground), I observed a female Red-eyed Cowbird among the branches of the same tree looking very melancoly. Suddenly she darted towards the nest, upon the side of which she perched, and immediately attempted to enter, but the vigilance of the fly-catcher was too acute, and observing the intrusion upon her sacred domicile, quickly attacked the Cowbird and drove her instantly away. I soon after saw the same bird examining the nest of the Mazatlan Oriole (Icterus pustulatus), but as there had been no egg yet laid in the nest, it did not seem to suit her, and she soon disappeared in the intricacies of the forests, leaving me strongly impressed as to her intentions .

In southern Arizona, we found eggs of the bronzed cowbird in nests of Scott’s oriole and the hepatic tanager .

Eggs: The eggs of the bronzed cowbird are indistinguishable from those of the red-eyed cowbird, described under that form. The measurements given by Bendire (1895) evidently include the eggs of both forms.

Plumages: The molts and plumages of this western race are similar to those of the eastern race, but the colors are somewhat paler and grayer in the immature plumages. The young male of this race is similar to the young female of involucratus, but decidedly paler. The adult male has violet rump and upper tail coverts.

Dickey and van Rossem (1938) write:

Neither sex reaches maturity until the first postnuptial molt. One-year-old males are variously intermediate in coloration between adult males and adult females, but acquire more of the male coloration at the time of the prenuptial molt in spring. One-year-old females are duller and less metallic than mature ones and are also slightly smaller. The annual (postnuptial) molt of the adults takes place in September and October. Adults as well as one-year-old birds have a spring molt, limited in extent and consisting chiefly of the replacement of a relatively few feathers about the interscapular region, breast and head.

Colors of soft parts: Adult males in winter: iris, brownish orange to orangebrown; bill, tarsi, and feet, black. Adult males in summer: similar, but iris, scarlet to crimson. Females (adult and birds of the year alike at all seasons): iris, similar to adult males in winter, but averaging paler; bill, tarsi, and feet, brownish or plumbeous black.

Food: The same authors found mio maize or Egyptian corn in two stomachs examined, miscellaneous seeds in nine and a caterpillar in one. Gilman (1914) says that they “stay around the barnyard where they pick up corn and other grains and scraps from the table thrown to the chickens; and they also remain around the school yard, where they eat watermelon set in the shade for birds of all kinds.”

Behavior: On this subject Dickey and van Rossem (1938) write:

Except during the breeding season, red-eyed cowbirds normally wander in large flocks. Occasionally they consort with the grackles, but as a rule each species is likely to keep pretty well to itself. The largest cowbird assemblages noted were a flock estimated at between 400 and 500, which was seen in some bare trees along the road near Santa Rosa on October 24, 1925, and another of about 100 which was beach-combing through the litter of the high-tide mark at Barra de Santiago on April 1, 1927. Groups of less than 50 were decidedly more numerous, and the average fall, winter, and early spring flocks contained 25 or 30 birds each.

The great disparity in the relative numbers of males and females is noticeable even in the winter flocks, but becomes still more apparent when the spring breakup occurs. About April 1 or even a little earlier, the flocks disintegrate into little bands consisting almost invariably of a single old male and his harem of four or five females. This small group retains its identity as a unit until the following fall. The male is in constant attendance, strutting with shoulder tufts raised and chest puffed out before first one and then another of his flock, who for the most part ignore him completely.

In southern Arizona, Harry S. Swarth (1929) observed: “Bands of six or eight attended individual horses or steers, often in company with Dwarf Cowbirds, trotting closely alongside the selected animal in order to take advantage of the small patch of shade it afforded, and showing a marked preference for feeding by the animal’s head.”

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Central Arizona to western Mexico .

Breeding Range: The bronzed cowbird breeds from central and southeastern Arizona (Wickenburg, Phoenix) and southwestern New Mexico (Guadalupe Canyon), south through central Sonora (Opodepe, Guaymas), western Ghihuahya (Durazno), and Sinaloa (Labrados, Presidio) to Nayarit (Tepic) and Colima.

Winter Range: Wmters throughout most of its breeding range north rarely to southern Arizona (Tucson).

Caaual records: Accidental in southeastern California (Havasu Lake).

Migration: The data deal with the species as a whole. Early dates of spring arrival are: Veracruz: southern Veracruz, April 12. Texas: Mission, April 17. Arizona: Tucson, April 11 (median of 4 years, April 23).

Late date of spring departure: Sonora: Rancho La Arizona, May 7.

Early date of fall arrival: Sonora: Rancho La Arizona, August 18.

Late date of fall departure: Arizona: Tucson, September 22.

Egg dates: Arizona: 9 records, May 30 to July 7; 4 records, June 12 to June 28. Texas: 44 records, April 1 to July 5; 22 records, May 12 to June 8.

******

Red-Eyed Bronzed Cowbird

TANGAVIUS AENEUS AENEUS (Wagler)

HABITS

The red-eyed cowbird is the best known and most widely distributed of the bronze-backed cowbirds. Its breeding range extends from eastern Texas (San Antonio) southward along the eastern coast region of Mexico and Central America as far as Panama. It differs from the type race of northwestern Mexico in having the back and rump entirely bronze color, thus lacking the violaceous rump of typical aeneus. The common names are not helpful in distinguishing our two subspecies, for both have red eyes and both have bronze backs .

Alexander F. Skutch contributes the following account of the distribution and haunts of this species in Central America:

“In northern Central America the red-eyed cowbird is found from the lowlands of both coasts far up into the mountains, breeding in the highlands of western Guatemala at least as high as 8,500 feet above sea-level. In southern Central America it is less widely distributed. In Costa Rica it appears to be absent from the heavily forested Caribbean lowlands and from the almost equally heavily forested lowlands on the Pacific side of the country, to the southward of the Gulf of Nicoya; but it is present in the drier lowlands around and to the north of the Gulf of Nicoya (Guanacaste), the central highlands, and the upper portions of the Caribbean slope. It avoids the forest, and its local (distribution is largely determined by the presence of open country. Hence it is more abundant in the highlands, where there is a dense human population, with many open fields and pastures, than in the less populous and more uniformly forested lowlands. For the same reason, it is more common in the dry and relatively open Pacific lowlands, and in arid, mountain-rimmed valleys in the Caribbean drainage, than in the heavily wooded coastal districts of the Caribbean; yet in Guatemala and Honduras it has invaded these districts where they have been extensively cleared for banana plantations and pastures. Red-eyed cowbirds often fly in compact flocks over some of the larger highland cities of Central America, and I have seen many of them in the central plaza of San Jose, Costa Rica.

“Red-eyed cowbirds perform at least short migrations, largely altitudinal, even in the tropical portions of their range. In the mountains above Tecpkn, Guatemala, I found them at between 8,000 and 9,000 feet only during the nesting season, from March until July. During this period they were a familiar sight in the pastures about the house which I occupied from early February until the end of the year. But in August they vanished, apparently having descended to lower and wanner regions, and were not seen again in this locality during the remainder of the year, although a few were found on the plateau a thousand feet lower. During the year I spent near Vara Blanca, living in a narrow clearing in the midst of the rain forest of this excessively wet region on the northern slope of the Cordillera Central of Costa Rica, at 5,500 feet above sea-level, the first red-eyed cowbird was seen on March 28, just as the nesting season was beginning for the majority of the local birds. I had been present in the same spot since the preceding July, without having seen a single individual. In this instance, I think it probable that the cowbirds had arrived from the cultivated lands of the central plateau to the south, passing over the continental divide, which here was about 6,800 feet high. To the north were scarcely broken forests leading down to the Caribbean lowlands, where the species is not known to occur.”

Courtship: A. F. Skutch (MS.) gives the following account of the courtship: “In the middle of March, I watched a flock of about 50 red-eyed cowbirds foraging in a compact group around a straw-pile beside a granary in the Guatemalan highlands, at an altitude of 7,300 feet. Apparently the birds were picking up waste grain. From time to time, from no apparent cause, they would all take wing in a body, wheel around in a close flock, then drop down again to continue their gleaning. The breeding season was approaching, and the male cowbirds were already in an amorous mood. Now and again one would rise a few feet into the air and hover prettily on beating wings above one of the females. Other males perched in the pine trees scattered about the field, where each spread and raised his cape until it surrounded his head like a black halo, and sang with low, squeaky whistles.

“One evening in July, at about sunset, I witnessed the courtship of a pair of red-eyed cowbirds beside the Ulna River in Honduras. The female was walking over a lawn, feeding, and the male followed her with his head thrown back, chest puffed out in front, and wings quivering, walking with a stiff, seemingly unnatural gait. Of a sudden he jumped into the air and remained for about a minute poised on vibrating wings, about a yard above the female. Then he dropped to the ground in front of her, and with out-fluffed plumage bobbed up and down by flexing his legs. She considered him for a moment, but apparently was not impressed by this gallant show, for she rudely flew away and left him to deflate himself all alone. Then he flew off m pursuit of her.”

Friedmann (1925) gives a slightly different account of the courtship:

On May 6, a pair of Red-eyes was found in a field and the male watched displaying to the female. Re ruffled up the feathers of his cape or mantle first and then all the feathers both on the upperparts and the underparts, brought his tail stiffly forward and under, arched his wings slightly, (not more than half as far as it was possible to arch them), and instead of bowing over forwards as does the male of the ordinary Cowbird, merely bent his head so that his bill was touching the feathers of his breast for its full extent. Then he suddenly bounced up and down four times, each bounce taking him about an inch from the ground. While bouncing up and down he gave a series of three very deep, guttural, yet bubbling sounds, and then a set of two short and one long squeaky, thin, high notes quite similar to the song of the ordinary Cowbird but wheezier, more throaty and shorter. Occasionally he did bow forward a little, but nothing like the extent to which M. eter does.

The sexual and territorial relations of the red-eyed cowbird are not well known. S. C. Merrill (1877), near Brownsville, Tex., found them scattered over the “surrounding country in little companies of one or two females and half a dozen males.” Friedmann (1929) states: “In this species the males outnumber the females to a somewhat greater degree than in any other Cowbird as far as I know. During my field work in southern Texas I saw remarkably few females compared to the number of males noticed.* * *

“That the males establish singing trees and territories is certain as I have noted in several instances that certain males were to be found every day in the same tree.”

Nesting: Merrill (1877) gives us our first information on the nesting of this cowbird, of which he says:

My first egg of Ae. AENEUS was taken on May 14, 1876, in a Cardinal’s nest. A few days before this a soldier brought me a similar egg, saying he found it in a Scissor-tail’s (Milvulus) nest; not recognizing it at the time, I paid little attention to him, and did not keep the egg. I soon found several others, and have taken in all twenty-two specimens the past season. All but two of these were found in nests of the Bullock’s, Hooded, and small Orchard Orioles (Icterus spurius var. affinis). It is a curious fact that although Yellow-breasted Chats and Redwinged Blackbirds breed abundantly in places most frequented by these Cowbirds, I have but once found the latter’s egg in a Chat’s nest, and never in a Red-wing’s, though I have looked in very many of them. * * * On six occasions I have found an egg of both Cowbirds in the same nest; in four of these there were eggs of the rightful owner, who was sitting; in the other two the Cowbird’s eggs were alone in the nests, which were deserted. * * * But the most remarkable instance was a nest of the small Orchard Oriole, found June 20, containing three eggs of census, while just beneath it was a whole egg of this parasite, also a broken one of this and of the Dwarf Cowbird.

Friedmann (1929) writes: “The Red-eyed Cowbird victimizes relatively few species of birds. The various species of Orioles seem to be the chief hosts of this parasite.” He says that the species, as a whole, “is definitely known to victimize eleven genera and seventeen species and subspecies, but about 75 per cent of all the eggs are laid in nests of Orioles. I have data on 76 victimized nests all in all and of these no less than 51 belong to four species of Icterus.” In addition to those mentioned above, he includes among the victims of the eastern race the western blue grosbeak, Audubon’s oriole, western mockingbird, Sennett’s thrasher, and the Texas wren.

Later (1931) he adds three more victims of the eastern race: the Mexican ground dove, the Rio Grande redwing, and Scalter’s towhee. And, in another paper (1933), he increases the list to 20 known forms and one hypothetical form, including such large birds as Couch’s kingbird, and the Costa Rican Thrush, as well as one vireo and four finches.

Eggs: Bendire (1895) describes the eggs of the red-eyed cowbird as “rather glossy; the shell is finely granulated and strong. Their shape varies from ovate to short and rounded ovate. They are pale bluish green in color and unspotted, resembling the eggs of the Blackthroated Sparrow and Blue Grosbeak in this respect, but are much larger.

“The average measurement of thirty-eight specimens in the United States National Museum collection is 23.11 by 18.29 millimetres, or 0.91 by 0.72 inch. The largest egg of the series measures 24.64 by 18.80 millimetres, or 0.97 by 0.74 inch; the smallest, 21.84 by 16.76 millimetres, or 0.86 by 0.66 inch.”

These measurements evidently include the eggs of both races of the species. Usually only one egg is laid in a nest of the host, but he mentions a nest of Audubon’s oriole that held three eggs of the oriole and three of this cowbird.

Young: Friedmann (1929) made the following observations on the growth and development of young red-eyed cowbirds:

I have not seen a newly hatched Red-eyed Cowbird but have found birds one day old. They resemble young Molothrus ater of corresponding age but are a little larger in size. The skin is orange-pink; the eye-skin greenish-blue: the bill and feet dusky yellowish, the claws light yellow; the gape of the bill swollen and white; the inside of the mouth reddish; the down mouse gray and present on the head, spinal, humeral, alar, and femoral tracts, longest on the head and shortest on the spinal tract; egg-tooth prominent and pyramidal in shape and about 1 mm. high.

On the second day the birds nearly double in weight; the skin becomes slightly tinged with brownish; no new neossoptiles appear and the old ones apparently do not increase in length.* * *

A four day old bird had the primaries and secondaries sprouted; the eyes were still closed; feather sheaths were present on all the tracts except the head where the greenish gray skin (formerly orange), was still covered with light mouse gray down. This bird when five days old measured 82 mm. in length, a considerable advance aver the previous day when it measured only 78 mm. The eyes opened on the fifth day and the sheaths of the rectrices began to push through the skin while those of the remiges began to open. The sixth and seventh days saw little change except growth and unfurling of the feathers from their sheaths .

The young Red-eye seems to get along with the rightful young in the nest better than do the young of M. bonariensis or M. ater and it sometimes happens that some of the rightful young survive with the parasite although in most cases the legitimate young last but a few days in face of the competition of the Red-eye. However, they do seem to survive longer with the young Red-eye than do young Sparrows or Warblers with the young of M. ater.

This may be partly due to the fact that the victims of the Red-eye are more nearly its own size than are those of the other Cowbirds.* * *

When about eleven days old the young Red-eyed Cowbird usually leaves the nest and as a rule stays nearby for several days. For about two weeks and possibly more it is cared for by its foster-parents and then shifts for itself. Usually by the time this happens the season is well advanced as the Red-eye is a fairly late breeder, and the young repair to the fields and marshes for the post-juvenal molt. In these places all the young congregate from all the surrounding countryside and when the molt is finished the birds come out in flocks.

Alexander F. Skutch has sent me these notes on the young of this species: “A nest of the green jay (Xantlzoura luazuosa) found near Matias Romero on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, on July 8, 1934, contained a single red-eyed cowbird [probably T. aeneus aesimilis], well feathered and almost ready to fly, sitting awake and alert between two young jays, larger than itself but naked and slumbering. A nest of the yellow-green vireo (Vireo flavoviridis), found near Colomba, Guatemala, on July 26, 1935, contained one cowbird nestling in addition to three young vireos. * * * In the dry country about Zacapa, Guatemala, on August 15, 1935, I saw a young cowbird being fed by a female oriole: apparently either Icterus guiana or I. pectoraiis, both of which were numerous in the neighborhood, and difficult to distinguish unless they are adult males. On June 14, 1933, I saw, on the edge of a maize field in the Guatemalan highlands at an elevation of 8,500 feet, a fledgling red-eyed cowbird attended by a pair of Guatemalan spotted towhees (Pipilo maculatus repetens). While the youngster clamored loudly for food, an adult cowbird alighted beside it, and after an interval touched its open mouth with her (?) bill, but I was too far away to see if any food was given. The adult cowbird then flew off, and the towhee came and fed the dusky fledgling.” This observation does not prove that the cowbird was feeding its own young, but is significant in connection with similar observations on the eastern cowbird by Fletcher (1925).

Plumages: The plumages and molts of the red-eyed cowbird differ from those of the eastern cowbird in that the young male does not acquire the adult plumage until after the first postnuptial molt, the second instead of the first fall; also, he has a partial spring molt.

Friedmann’s (1929) descriptions of the plumages and molts of the male are as follows: The juvenal plumage is “dull sooty black or dark sooty, the feathers of the underparts of the body with more or less distinct narrow margins of paler; mandible brownish basally.” The first winter plumage, acquired by a complete postiuvenal molt, is “dull black, the underparts, especially the throat sometimes dark sooty brownish; back and scapulars very faintly, the wings, upper tail coverts and tail strongly, glossed with bluish green; bill, legs and feet black. Young males in this plumage are similar to adult females.

“First Nuptial Plumage acquired by wear which shows very little, and to a slight extent by molt involving the head and neck and breast. Plumage similar to the first winter plumage but the head, neck, and breast dull bronzy.”

The adult winter plumage is acquired by a complete postnuptial molt; in this the head, neck and body are “greenish bronze, rump like the back, the plumage soft and silky but not as smooth as in T. a. aeneus; ‘presenting the appearance of having been wet and imperfectly dried’ (Ridgway); tail coverts blue-black, the upper ones glossed with violet; wing coverts glossy dark greenish blue, brightest on greater coverts and tertials, less bright as well as more greenish on primaries, primary coverts and alula; lesser wing coverts dark metallic violet, the middle coverts violet-bluish; tail dark metallic bluish-green or greenish-blue; bill black; iris red; legs and feet black or blackish brown.”

The adult nuptial plumage is acquired by wear and is only slightly brighter.

In the female the molts are the same as in the male. The juvenal plumage is similar to that of the male but paler and grayer, “above sepia or grayish sepia; beneath paler and grayer, with indistinct narrow paler margins to the feathers.” The first winter plumage is “dull black, the underparts, especially the throat sometimes dark sooty brown; back and scapulars very faintly, the wings, upper tail converts and tail strongly, glossed with bluish-green; neck ruffs much less developed than in the male. The female of this race is much darker than that of T. a. aeneus.” Adults and young are practically alike in winter plumage.

Food: Friedmann (1929) writes:

As far as my observations go, the Red-eyed Cowbird is entirely graminivorous in its food habits but I feel that more extensive data would show it to feed upon insects as well. The gizzards of some twenty-odd specimens collected during May, 1924, near Brownsville, Texas, contained only weed seeds and a few oats. The oats were undoubtedly picked up in the cavalry stable yards at Fort Brown. As many as 1,500 small grass seeds were found in a single stomach and most of the birds examined had consumed large numbers of these seeds. From this it may be judged that the species is highly beneficial in its food habits although its activities at times in fields of ripening grain or rice might be less creditable, but of this we know nothing as yet.

The Red-eye associates considerably with cattle and in all probability does so for the insects it finds scared up by the grazing animals, but my stomach content examinations have failed to reveal even a trace of insect food.

In southern Vera Gruz these cowbirds evidently do considerable damage to grain crops, for Alexander Wetmore (1943) says:

Red-eyed cowbirds were found in small flocks, regularly at the village, and also around the lagoons. As the corn matured they spread out through the fields to feed on the grain in company with Cassidix, and at times I saw them in such localities in flocks. When the ears were ripened the natives went into the fields to bend or break the stalks at an abrupt angle below the ears, so that these instead of standing upright were turned down toward the ground and were covered by the stalks above. Whole fields treated in this way presented a curious appearance. The theory was that the ears were thus hidden so that they were protected from damage by birds. Before this, while grain was in the milky stage, men and boys went out at dawn to the fields armed with slings and slingshots, or with clods to be thrown by hand. They stood on small elevated platforms of poles that gave them clear view across the corn, where by shouting or by casting missiles they kept the birds moving and so prevented damage.

Alexander F. Skutch contributes this account of the feeding habits: “True cow-pen birds, the red-eyed cowbirds often forage close beside the heads of grazing cattle, snatching up the insects which the animals stir up from their lurking places amid the herbage. They also alight upon the backs of horned cattle and mules to vary their diet with ticks and insect pests which they pluck from the animals’ skin. Often they forage in the pastures in company with the far bigger giant cowbirds (Psomocolax oryzivorus) and groove-billed anis.

“The red-eyed cowbirds also joined the giant cowbirds and other members of the Icteridac in another and most unexpected form of hunting. Along the Rio Morj~, a small tributary of the Rio Motagua in Guatemala, was a broad, bare flood plain, covered with small, water-worn stones, where I could count upon watching the cowbirds feed almost every evening, from an hour or so before sunset until the sun had sunk behind the cane brakes. The giant cowbirds formed the nucleus of these assemblages, but their party was joined by red-eyed cowbirds, a few great-tailed grackles (especially the males), and Sumichrast’s blackbirds (Dives dives). Often a few wild Muscovy ducks would forage near these smaller birds in the shallows; at a little distance, all five species appeared sufficiently black to remind me of the truth of the old adage ‘Birds of a feather flock together’. For some reason, the male giant cowbirds resented the presence of the male redeyed cowbirds and often pursued them, although they never drove them far away.

The chief occupation of both kinds of cowbirds was stone-turning, for which their strong, black bills seemed well fitted. They moved stone after stone, turning over the smaller ones, pushing aside those which were somewhat larger, and merely raising slightly one side of the biggest, to see what edible matter might lurk beneath them. The Sumicbrast’s blackbirds and the great-tailed grackles joined in this pursuit, but not so energetically as the cowbirds; for the grackles especially preferred to hunt, small creatures that lurked in the shallows, where the other stone-turners rarely ventured. All four of these blackish members of the troupial family turned their stones in exactly the same fashion: the bird’s head was lowered and the tip of its bill inserted beneath the near edge of the stone and pushed forward, in the line of advance of the bird. As the decisive push was delivered, the bird’s lower mandible was dropped somewhat and its bill held slightly open. Whatever small animals lay concealed beneath the stone were eaten, then the bird proceeded to move another.”

Behavior: Skutch (MS.) remarks on their behavior: “As evening fell, the red-eyed cowbirds and the Sumichrast’s blackbirds finished their supper gleaned from the stony flood plain and retired to roost in a dense stand of young giant canes (Gynerium sagillatum) growing behind the barren flats. Until they fell asleep, the blackbirds continued to utter a delightful variety of clear and soothing whistles, but their companions the cowbirds were rarely heard.”

Voice: Friedmann (1929) writes:

The song is confined to the male and is quite similar to that of the ordinary Cowbird (Molothrus ater) but wheezier, throatier, the individual notes shorter and the preliminary guttural notes deeper. It may he written as follows ugh gub tse ~,ss tseeee. Frequently the three first notes are omitted and sometimes the last two are run together. I have heard the song given by birds while flying and also while on the ground. Strangely enough I never heard it from a bird in a tree although Visher’s experience (see above) was just the reverse.

The call notes of the Red-eyed Cowbird are not yet well known and are worth careful study. In my experience with this species, call notes were rarely heard and the few that were noted were all of one type, a harsh, beady, almost rasping chuck. This note seemed to be a feeding note and was used by both sexes. I never saw or heard anything to indicate that the birds have any other call notes.

Field marks: The red-eyed cowbird is larger than the common cowbird, nearly the size of Brewer’s blackbird, with which it is often associated, but the cowbird’s eye is red, while that of the blackbird is yellow; and the cowbird has a stouter, more conical bill than the blackbird and its bronzy color is conspicuous, contrasting with the violaceous-green wings and tail. The blood-red eye of this cowbird is distinctive when near enough; and in the mixed flocks of blackbirds it can often be recognized by its top-heavy appearance due to the puffing out of the feathers of the head and neck, forming a sort of ruff.

Winter: The red-eyed cowbird is only partially migratory in the lower Rio Grande Valley. Merrill (1877) says; “Here they are cornmon throughout the year, a small proportion going south in winter. Those that remain gather in large flocks, with the Long-tailed Grackles, common Cowbirds, and Brewer’s, Red-winged, and Yellow-headed Blackbirds; they become very tame, and the abundance of food about the picket-lines attracts them for miles around.”

DISTRIBUTION

Range: South-central Texas to eastern and north-central Mexico.

Breeding Range: The red-eyed bronzed cowbird breeds from south-central Texas (Eagle Pass, Lee County), and the Yucat~n Peninsula (Chichen Itza, San Felipe) south through Central America to western Panama (Calobre, Chitrra); west to Nuevo Leon (Galeana, Linares) and eastern San Luis Potosi (Valles, Tamazunchale).

Winter Range: Winters throughout iiiost of breeding range except north only to southern Texas (Edinburg, Aransas Pass