The Black-billed Cuckoo is much less frequently seen than its relative, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo. It is more secretive, and is often vocal at night. Black-billed Cuckoos have declined substantially, perhaps due to increased pesticide use and a resulting reduction in food supply.

The favorite food of the Black-billed Cuckoo is caterpillars. If a tree is covered with caterpillars, a cuckoo can eat up to 15 of them in a minute. A cuckoo’s stomach can hold hundreds of small caterpillars, or dozens of large ones.

On this page

Description of the Black-billed Cuckoo

BREEDING MALE

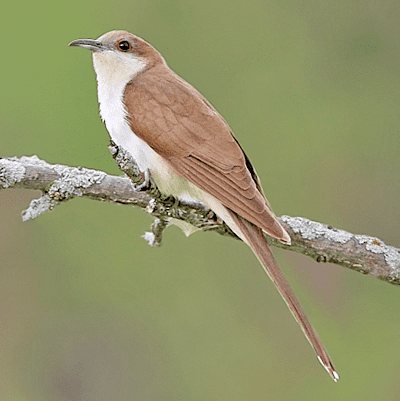

The Black-billed Cuckoo is a relative of the Mangrove and Yellow-billed Cuckoos, and has a long tail marked below with small white spots, a stout, gray to black bill, brownish upperparts with brownish to slightly rufous primaries, and white underparts. Length: 12 in. Wingspan: 17 in.

Female

The sexes are similar.

Seasonal change in appearance

None.

Juvenile

Juveniles are similar to adults, but have no or very minimal white in the tail.

Habitat

Black-billed Cuckoos inhabit woodlands and streamside thickets.

Diet

Black-billed Cuckoos eat insects, especially caterpillars.

Photograph © Nick Saunders.

Behavior

Black-billed Cuckoos forage slowly within trees and shrubs.

Range

Black-billed Cuckoos breed throughout much of the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and southern Canada. They winter in South America. The population is declining.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the Black-billed Cuckoo.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

Black-billed Cuckoos are rather secretive, and are frequently heard before they are seen.

Tent caterpillar outbreaks provide a feeding bonanza for Black-billed Cuckoos.

Black-billed Cuckoo clutch sizes increase when food is abundant.

Vocalizations

The song consists of a series of a rhythmic “ku ku ku ku ku.”

Similar Species

Yellow-billed Cuckoo

Yellow-billed Cuckoos have a mostly yellow bill and much larger white tail spots, as well as extensive rufous in the primaries.

Nesting

The Black-billed Cuckoo’s nest is a loose stick platform placed in a tree.

Number: 2-3.

Color: Bluish-green in color.

Incubation and fledging:

The young hatch at about 10-11 days, and leave the nest in about another 6-8 days, though continuing to associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Black-billed Cuckoo

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Black-billed Cuckoo – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

COCCYZUS ERYTHROPTHALMUS (Wilson)

The black-billed cuckoo is not so widely distributed as the yellow billed, being confined in the breeding season to practically the northern half of the United States and southern Canada east of the Rocky Mountains. Within this range it seems to be commoner northward and rarer southward than the other species, ranging farther north and not so far south.

In appearance and habits our two cuckoos are very much alike, and their haunts are similar; both are often found together, or in similar places, though the black-billed is rather more of a woodland bird and rather more retiring than the yellow-billed. William Brewster (1906) says that in the Cambridge region it is “more given to haunting extensive tracts of dry upland woods and to nesting in wild apple trees, Virginia junipers and barberry bushes in remote rocky pastures such as those which lie scattered along, the crest and sides of the high ridge between Arlington and Waverley.

Courtship: William Brewster (1937a) writes: “On July 15, 1908, 1 witnessed the coition of two Black-billed Cuckoos in woods near Bethel, Maine. It took place on a branch only three or four feet above the ground. Although performed listlessly and intermittently, it was singularly protracted, for the two birds remained together at least four or five minutes, and did not finally separate until disturbed by my approach, when the male flew away and presently sang once. The female stayed quietly on her perch until I got near enough to see- that she was a fully adult bird.”

Nesting: Most of the New England nests on which I have data were placed at low elevations, 2 to 4 feet above ground, in various small trees, bushes, or thickets. My first nest was the highest, 10 feet up, in the top of a leaning black birch in a strip of swampy woods and brushy thickets along a small brook. Another was 8 feet from the ground in a dense thicket of shrubbery and blackberry vines. Three nests were in small white pines, 3 to 4 feet up, in rather open spaces overgrown with various shrubs and small trees near the edges of the woods; the nests were placed on horizontal branches, against the trunk, and well concealed among the dense branches. Near Asquam Lake in New Hampshire I saw two nests in thick clumps of mountain-laurel in some dense and heavy deciduous woods, where the land sloped down to the lake; the mountain-laurel grew here in extensive patches, but not very high, seldom over 3 or 4 feet; the large and well-made nests were only 2 and 3 feet from the ground, but fairly well concealed.

Some nests of the black-billed cuckoo are very flimsy affairs, but often they are much more substantially built than the nests of the yellow-billed cuckoo. Owen Durfee describes in his notes a well made nest that he found in a clump of chinquapin oaks near a road in Rehoboth, Mass. It was made of oak twigs and dry fern stalks, many of the twigs being fresh, with leaves attached; it was lined with dry oak leaves and a few fresh ones. It measured 8 inches in outside diameter and 3 by 31/2 inches in inside diameter, being hollowed to a depth of I inch. There is a beautiful nest in the Thayer collection, taken from a thicket in Lancaster, Mass., 7 feet from the ground; it has a well-made foundation of coarse twigs, tufts of grass, and burs; and it is profusely lined with the green leaves and the cottony catkins of the poplar. S. F. Rathbun writes to me of an interesting nest that lie found: “The nest was a saucer-shaped affair made entirely of the burs from the burdock plant, simply stuck together so as to form a shallow receptacle for the eggs. As a lining for the nest a few dry grasses were used, and the burs with the grasses represented the entire structure. The cuckoo certainly showed ingenuity when it made this nest, for it could not have been more simply or easily constructed.”

Dr. T. C. Stephens has sent me some fine photographs (pl. 8) of a black-billed cuckoo’s nest taken at the base of a willow sapling, near the shore of Lake Goodenough, in Union County, S. Dak., and says: “I have observed a rather marked tendency for the black-billed cuckoo in this region to build its nest within a very few inches of the ground or on the ground. This nest in the photograph was several inches above the ground outside the clump, but it might be regarded as a ground nest, because there was quite an accumulation of dirt and weed growth immediately below it. Of course, I have found nests of this species at heights about level with 9, man’s eyes, also.”

A. Dawes DuBois has sent me the data for eight nests of this cuckoo, as found by him in Tompkins County, N. Y., and Hennepin County, Minn. Two of them were 5 feet above ground, one in the top of a bush covered with grape vines on the steep slope of a ravine and the other in a small larch, in the midst of an extensive willow thicket, half a foot from the trunk of the tree on a branch where two branchlets were attached. One of the lowest two was not over a foot above ground, among weeds 2 feet high; the nest was supported by a small dead branch that had fallen from a tree and lay hidden in the weeds. Others were at intermediate heights in more normal situations. The nest in the small larch tree he describes as made first of some cottony seed pods (ripened willow catkins), then a main structure of woody twigs, and lined with finer twigs, a. few grasses and bits of the cottony seed pods; two tufts of dry grass, with roots attached, were at opposite sides of the rim.

Major Bendire, (1895) says:

The nests of the Black-billed Cuckoo appear to be slightly better built than those of the Yellow-billed species; the platform is usually constructed of finer twigs, the soft inner bark of cedar, fine rootlets, weed stems, etc., and there is generally more lining. This consists of the aments of oak, white and black ash, and maple, willow catkins, and the flowers of the cudweed or everlasting Wnaphalium), dried leaves, and similar materials. The majority of the nests are placed In rather low situations, mostly not over 6 feet from the ground, on horizontal limbs of bushy evergreens, pines, cedars, and hemlocks, or in deciduous trees and shrubs, such as the box elder, chestnut, thorn apple, and beech trees; also in hedges, briar and kalmia patches, occasionally on old logs, and now and then even on the ground.

A rather high nest was found by P. G. Howes (1908) near Stamford, Conn. It was about 15 feet from the ground, at the extremity of a limb of “a scrubby apple tree at the foot of a hay-covered field.” He says that, in his experience, the nest “has always been lined with maiden-hair ferns.”

H. W. Flint, of Stamford, Conn., in a letter to Major Bendire (1895), mentions a still higher nest, and says: “I know of one spot in this vicinity where the Black-billed Cuckoo might almost be said to breed in colonies-a sloping hillside near a traveled road. Here I have found seven nests of this species within an hour, none of them placed over 3 feet from the ground. I have also frequently found their nest on a fallen limb, the top of which was resting upon underbrush. As an exception to their low nesting, I once found a nest containing two well-feathered young and two fresh eggs over 18 feet from the ground, placed in the top of a cedar tree, in a dense thicket of other cedars.”

As already mentioned under the preceding species, both cuckoos often lay their eggs in each other’s nests. Thornas Mellwraith (1894) mentions three cases of parasitism on the part of the black-billed cuckoo, as observed by Dr. C. K. Clarke, of Kingston, Ontario; he says:

The first birds Dr. Clarke observed being imposed upon were a pair of chipping sparrows, who raised the young cuckoo at the expense of the family.

Next carne a pair of yellow warblers, whose protege soon crowded out the legitimate occupants of the nest. They were raised from the ground and placed within reach, but the big boy required all the attention of the foster-parents, and the others died. During the whole period, the old cuckoo was always to be found flitting about in a restless manner, as if she had some doubt in regard to the ability of the warblers to take care of her child.

The third case was another pair of chipping sparrows, in whose nest the cuckoo was observed sitting, and from which she did not move till the observers almost touched her. The result was the same as in the other cases. The young cuckoo threw the sparrows out as soon as she had strength to do so.

Eggs of the black-billed cuckoo have also been found in nests of the wood pewee, cardinal, cedar waxwing, catbird, and wood thrush. Under the preceding species will be found a note, published by J. L. Davison (1887), describing the finding of a. nest occupied by a robin, a yellow-billed cuckoo, and a mourning dove. Bendire (1895) published an almost identical account of such a remarkable occurrence, on the authority of the same observer, but with the black-billed substituted for the yellow-billed cuckoo. It seems hardly likely that such an unusual happening could occur with both species in exactly the same way, and leaves us in doubt as to which species of cuckoo was involved.

Eggs: The black-billed cuckoo commonly lays 2 or 3 eggs; sets of 4 or 5 may sometimes be the product of a single pair; but the larger numbers that have been found in their nests, 6, 7, or even 8 eggs, were probably laid by two or perhaps three females, as these birds are notoriously careless about laying in each other’s nests. Bendire (1895) says: “The eggs of the Black-billed Cuckoo are more nearly oval than elliptical oval, and shorter and rounder than those of the Yellow-billed Cuckoo, and much more deeply colored. Like these, they are unspotted; the shell is thin and fine grained, with little or no gloss. Their color is difficult to describe exactly, varying from nile blue to pale beryl green, and occasionally the shell shows a decidedly marbled appearance, caused by different shades running into each other. * * * Aside from their deeper color, they are also readily distinguished from eggs of the Yellow-billed Cuckoo by their smaller size.”

Eggs that I have seen in collections I should describe as “pale glaucous green,” “dull opaline green,” or “microline green” and varying from oval to elliptical-oval. Some of these, as well as some of those included in the following measurements, may be yellow-billed cuckoos’ eggs, as the two are probably not always recognizable with certainty. The measurements of 54 eggs, presumably of this species, average 27.18 by 20.57 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 30.48 by 22.86, 22.61 by 18.80, and 25.40 by 18.29 millimeters.

Young: Incubation is shared by both sexes and lasts for about 14 days. As the eggs are often laid at infrequent intervals, it is not unusual to find young birds of different ages, or even eggs and young, in the same nest. Both sexes assist in the care of the young and are devoted parents; even when an egg is hatched by a foster parent, the mother cuckoo does not seem entirely to lose interest in her youngster, as related above. On the other hand, William H. Moore (1902a), of Scotch Lake, New Brunswick, says: “I have known this bird to desert its young when the nest was molested, and after the, young died they were covered with leaves by the adults.” Cuckoos are careless about removing the cast-off shells, which are often found in the nest after the young have hatched. The young remain in the nest 7 to 9 days after hatching and then become quite precocial. While in the nest the young are fed by their parents in a rather peculiar manner, of which Dr. Thomas S. Roberts (1932) writes:

When the old bird returns, the food, which is very likely to be live caterpillars, Is concealed in the throat. As a nestling raises its head with open mouth and rapidly vibrating wings, the parent thrusts its bill deeply into the open maw and the young bird grasps securely the smooth bill of the old bird, in which action it Is greatly aided by several soft papillae or disks in the roof of the mouth. Then, with a slow, pumping motion, the squirming caterpillars are transferred with some difficulty from one mouth to another. The process is a slow one, the birds being attached a minute or more and the transfer aided, apparently, by a sucking effort on the part of the nestling.

When a young Cuckoo opens its mouth widely there are visible, in the roof of the mouth, a number of large, flat-topped, white papillae or tubercles, arranged symmetrically, the function of which is plainly to make it possible for the nestling to maintain its hold on the parent’s bill, which is smooth and tapering. A small finger-tip Inserted well down into the open, upturned mouth of a nestling is seized tightly and a sucking motion is distinctly perceptible.

Prof. Francis H. Herrick (1935) has made a thorough study of the home life of the black-billed cuckoo, and I cannot do better than to quote a few of his remarks on the behavior of the young. After describing the peculiar appearance of the newly hatched young, he says:

More remarkable than anything about its appearance, however, is the muscular vigor and endurance the cuckoo displays at this tender age, for it seems to be able to withstand heat, hunger, and general neglect that would be fatal to the young of most wild birds. I soon found by experiment that when barely three hours out of its shell this little cuckoo could hang suspended by a leg or even by a single toe for upwards of a quarter of a minute, and that it could raise itself up until Its bill was well over the twig that it grasped with both feet; and in a short time it was able to raise itself on to the twig, or even to draw itself up with the power of one leg, which implies an extraordinary muscular development. * * * Though born blind and essentially naked, the young black-bill is neither deaf nor dumb, and in proportion to its size it is probably the strongest and most enterprising altricial nestling on the North American continent. * * *

Like other nestlings, the cuckoo lies flat, with toes clenched, and holds to its fragile nest with a firm grip. Attempt to remove it, and it is likely to pull its nest to pieces rather than loose its hold; or it may even drag out a fellow nestling, reminding one of crayfishes or lobsters, in the handling of which one may also get a living chain. Should you succeed in displacing a bird, its claws will rapidly open and close in its desperate search for any object to clasp, for a contact stimulus afforded by any solid body can alone satisfy this strong reflex. * * *

At the age of about six days the nestling cuckoo has reached that peculiar transitory state which we may call the “quill” or feather-tube stage. * * *

Towards the end of this brief and unique stage the behavior of the young bird changes in marked and rapid fashion. It Indulges in new attitudes, acquires new call and alarm-notes, shows fear, and begins those preening or combing movements which are to effect a relatively sudden and altogether surprising change in Its appearance. * 0 *

In one instance the first preening action was noticed on the sixth day; thereafter this kind of activity became frequent, and the bird would comb every “quill” within reach, drawing the mandibles over it from base to apex. Then, with apparent suddenness, at the close of the seventh day the transparent horny sheaths began to give way at their base-instead of wearing off gradually from apex to base in the usual fashion-and were raked off by the mouthful. * * *

Fear may become manifest as early as the sixth day, when a frightened bird will sometimes clear the nest at a bound and, seizing a branch with both feet, hold firmly to it. Should it drop to the ground, it can make off with surprising speed. If captured and held, it will emit loud, explosive squeals, than which nothing seems to arouse its parents to quicker attack or bolder measures. Replace It in the nest, and it spreads its wings, stiffens, and lies flat with every feather-tube on end; and It will repeat these defensive measures as often as it Is touched or disturbed. 0 0 *

When from seven to nine days old, with half of its feathers unsheathed, the cuckoo suddenly leaves its nest and enters upon a climbing period, which lasts about a fortnight or until it is able to fly. At one of my observation stations I saw three young birds leave their nest In succession, and the procedure in the case of the oldest one was particularly interesting. This bird, which bad been sitting in the bright sunshine, for the day was not uncomfortably warm, of a sudden moved to one side of Its platform. After having combed off several mouthfuls of feather-sheaths, it sat upright for some minutes and gazed into Its outer world. Then, directing its attention to a small branch and ducking Its head as if contemplating flight, with a leap it cleared the nest, and, catching hold of a twig, with both feet, It swung free with acrobatic dexterity. In another moment It had pulled itself up and was comfortably perched. If such a first perch is placed in the shade and the young bird is promptly fed, it may keep to It for a long time; but It can move about, and should It drop to the ground, It can mount to safety again.

The vertical position assumed by young cuckoos, probably as a hiding pose, has been noted by several observers, but the following incident reported to me in a letter from Frederic H. Kennard, is quite unusual; he says: “I had just been investigating a big highbush blueberry bush, looking for a nest, when I discovered, to my surprise, a fledgling black-billed cuckoo, squatting on a twig about 6 feet from the ground. The little bird, which really was not able to fly, was squatting on a limb, just as little birds ordinarily do; his wing feathers were fairly well developed, but his tail was only about a quarter of an inch long. When I parted the branches a trifle, so that we could see him better, and finding out that he was discovered, he promptly assumed an almost perpendicular position, with his neck stretched out almost unbelievably and his bill almost straight in the air; and there he sat, immovable, with his bill in the air like a bittern, only oscillating a trifle when the branch on which he was sitting was disturbed a little by the breeze.

“My youngest soil, Jack, being interested in the peculiarities of cuckoos’ feet, attempted to pick him off the limb; the little bird fluttered to the ground, where he picked him tip. When we had dill , NT examined and discussed the arrangement of his toes, Jack endeavored to put the little fellow back exactly where he had been when we first, disturbed him. Then, as he endeavored to replace him oil the limb, be suddenly went limp and, apparently, passed out in his hand, frightened to death, as I supposed. He was perfectly limp and my impression is that his eyes were closed. Jack finally, in trying to get him to stay on the limb, hung him across the limb by the neck, with his head across one side and his body down the other side. Just then there came a little breeze, the body dropped, and that little bird simply scuttled in under the ferns. It was the most astonishing performance that I ever witnessed, first the stake-driver attitude, as a protective position, and then playing dead.”

Plumages: Professor Herrick (1935) says of the newly-hatched young cuckoo: “Although most birds emerge from the shell wet with the amniotic fluid, the cuckoo just mentioned came out quite dry. It was two and one-half inches long and weighed less than a quarter of an ounce (or 7.4 grams). Its skin was coal-black, sparsely sprinkled with sharply contrasting snow-white ‘hairs’-in reality the feather-tubes of a rudimentary down which never unfolds. These primitive feather-tubes are later pushed out by those of the juvenal contour feathers and for about a week are borne upon their tips, thus giving them a peculiar flagellate appearance.”

When about six days old, the young cuckoo “bristles like the fretful porcupine in every feather-tract”; these bristles are the feather-tubes of the juvenal plumage, referred to above. At about this age, the young bird begins the “combing” process, by which the sheaths of these feather tubes are removed, as described above, and a marvelous change begins to take -place in a remarkably short time, as the sheaths are removed and fall in a shower in and about the nest. Professor Herrick (1935) says: “Thus at one stroke one or more of the juvenal contour feathers are exposed and quickly fluff out in all their shapely proportions. * * * The change actually occupies about twelve hours, and it is really not complete, since the sheaths of the wing- and tail-quills flake off gradually, as in other birds, and those feathers of head and neck out of reach of the ‘comb’ remain sheathed for a considerable time longer.”

By the time that the young bird leaves the nest, at the age of 8 or 9 days, it is in nearly full juvenal plumage; the wings are fairly well grown, but the tail is still very short. In this plumage the soft plumage above is “buffy brown,” each feather tipped with white; the under parts are silvery white, tinged with pale gray on the belly and with pale buff on the breast and throat. During late summer and early fall, most, if not all, of this juvenal contour plumage is molted and replaced by the first winter plumage, but the flight feathers of the wings and tail are retained until spring. This first winter plumage is much like that of the adult, but it is more brownish on the bead and back and more greenish olive on the scapulars than in adults; the throat is more buffy and the upper breast more grayish buff than in the adult; the young bird’s tail is quite different, the grayish white tips are smaller and are not bordered inwardly with the dusky space, which is clearly visible in the adult tail. The molts are apparently the same as in the yellow-billed cuckoo; the adult plumage seems to be acquired before the young birds return from their first winter in the south, but we have no specimens showing a spring molt.

Food: The black-billed cuckoo is just as good a caterpillar destroyer as the yellow-billed; in fact the food habits of the two species are almost identical in all respects. An abundance of caterpillars in a locality is very likely to bring with it an invasion of cuckoos. Frank L. Farley writes to me: “As far as I am aware, the black-billed cuckoo was unknown in central Alberta until the summer of 1923. That year the central portion of the Province was infested with tent caterpillars, which, in 1924-25, assumed plague proportions. Entire bluffs of poplar trees, several acres in extent, were entirely denuded of their leaves, while houses and other buildings were overrun with the pests.” In June 1924 the cuckoos began to appear for the first time, birds entirely unknown to the residents. “Although caterpillars gradually disappeared after 1925, cuckoos were reported from widely separated parts of central Alberta, the most northerly one being about 150 miles north of Camrose, which is in latitude 530 N. The presence of cuckoos and caterpillars in the same territory during these years would tend to bear out the claims of other observers, that the insects are particularly relished by these birds, which, in some uncanny manner, are able to locate infested territory far removed from their usual place of residence.”

Forbush (1927) says:

In seasons when caterpillars of any species are abundant, cuckoos usually become common in the infested localities. They follow the caterpillars, and where such food is plentiful, the size of their broods seems to increase. During an invasion of forest tent caterpillars in Stoneham, Massachusetts, in May, 1898, Mr. Frank H. Mosher watched one of these birds that caught and ate 36 of these insects inside of five minutes. He saw another in Malden eat 29, rest a few minutes and then eat 14 more. In July, 1899, he reported a family of these birds In a locality infested with the Gypsy moth, and said that they were eating large quantities of Gypsy caterpillars. In June, 1895, Mr. Henry Shaw reported great numbers of these Cuckoos in Dorchester feeding on the same pests. The late Professor Walter B. Barrows, of Michigan, an extremely conservative ornithologist, is responsible for the statement that in several Instances remains of over 100 tent caterpillars have been taken from a single cuckoo’s stomach. The Black-billed Cuckoo, because more common than the Yellow-billed, is the species that most commonly attacks this Insect in New England orchards. During an invasion of army worms, Professor S. A. Forbes found that 95 per Cent of the food of this species consisted of that Caterpillar.

F. H. King (1883), writing of the food of the black-billed cuckoo in Wisconsin, says: “Of thirteen specimens examined, nine had eaten caterpillars-among them were eight of the fall web-worms (Hyphantria textor), thirty-three of the oak caterpillars (Dryocampa senatoria), one of the lo caterpillars (Saturnia io), six of the antiopa caterpillars (Vanessa anfiopa), and one of the caterpillars of the archippus butterfly (Danair archippm). One contained five larvae of the large saw-fly (Cyinbex americana) ; six, twenty-five grass hoppers; one, a cricket; two, ten beetles; and two harvest-men.”

Other authors have charged this cuckoo with eating minute mollusks and other small animals, fishes and aquatic larvae, fruits and berries, and even the eggs and young of small birds. On the latter point, Henry D. Minot (1877) says that “they do great mischief in destroying the eggs of other useful birds. Like arrant cowards, as they are, they take opportunities to approach stealthily the nests of many birds, whom they would be afraid to encounter, and then feast on the eggs of the absent parents, after which they hurry away. They are scarcely less destructive in this way than the black snakes, though I have never known them to kill young birds.”

Behavior: The two cuckoos are so much alike in haunts, habits, and behavior that most of what I have said about the yellow-billed would apply equally well to this species. The black-billed is rather more swift on the wing than the other, but it flies in the same graceful manner. It is the same shy recluse of the shady retreats, among the dense foliage of the woods and shade trees, unafraid to frequent the orchards and gardens in search for its food, but shunning any intimacy with human beings; we hear its wandering voice but seldom see more than a fleeting glimpse of its graceful form as it fades away into the shadows.

In defense of its eggs or young the black-billed cuckoo is often quite courageous. Olive Thorne Miller (1892) writes charmingly of her experiences with an incubating pair of these cuckoos; she watched them change places on the nest, and found the female quite confiding, but the male never became reconciled to her presence:

It happened that I arrived when the mother was away, and the head of the household in charge. No sooner did I appear on the path than he flew off the nest with great bustle, thus betraying himself at once; but he did not desert his post of protector. He perched on a branch somewhat higher than my head, and five or six feet away, and began calling, a low “coo-oo.” With every cry he opened his mouth very wide, as though to shriek at the top of his voice, and the low cry that came out was so ludicrously inadequate to his apparent effort that it was very droll. In this performance he made fine display of the inside of his mouth and throat, which looked, from where I stood, like black satin. * * *

Finding that his voice did not drive me away, the bird resorted to another method; he tried intimidation. First he threw himself into a most curious attitude, humping his shoulders and opening his tail like a fan, then spreading his wings and resting the upper end of them on his tail, which made at the back a sort of scoop effect. Every time he uttered the cry he lifted wings and tail together, and let them fall slowly back to their natural position. It was the queerest bird performance I ever saw.

On another day, she says: “We had not waited long when the head of the cuckoo family appeared. He saw us instantly, and, I regret to say, was no more reconciled to our presence than lie had been on the previous occasion; but he showed his displeasure in a different way. He rushed about in the trees, crying, ‘cuck-a-ruck, cuck-a-ruck,’ running out even to the tip of slender branches that seemed too slight to bear his weight. When his feelings entirely overcame him lie flew away, and though we remained fifteen minutes, no one came to the nest.”

E. A. Samuels (1883) writes:

Like the other, the Black-billed Cuckoo Is very cowardly, and is quickly driven from the neighborhood of the nest of almost any of the other birds. If a robin, or other bird of equal size, discover one of these, to him pirates, in the vicinity of his nest, he immediately assaults the intruder, with loud outcries, pouncing upon him, and pecking with great ferocity. Others of his neighbors, who are near, join in the attack; the Cuckoo, in retreating, dives into the recesses of a stone. wall, or the first secure retreat available; very seldom taking to his wings, as another bird would do. I have known of a cuckoo being driven into a barn by a Blue-bird (S. siahs). who sat perching oil a fence outside for several minutes, keeping his enemy prisoner; and the latter, when pursued and captured by myself, preferred being my prisoner to facing his enemy outside.

Voice: One cannot always distinguish with certainty all the notes of the black-billed cuckoo from all those of the yellow-billed. Many of the notes are much alike in both species. The notes of the black billed are, as a rule,-softer and more liquid than those of the yellow billed and not so deep-toned.

The ordinary “song” of the black-billed is preceded by a gurgling note, and the rest of the long song is uttered in regularly measured time, not retarded at the end, as is that of the yellow-billed, and the notes are given in couplets or triplets, one syllable in each set being accented. Dr. Charles W. Townsend (1920a) describes it very well as follows: “The full song may be described as a preliminary harsh clearing of the throat followed by from six to twelve short coughs which in turn are succeeded by the more pleasing doublets and triplets of cows. The Yellow-billed Cuckoo repeats his cows or cowks in regular order without dividing them into sets and they sound as woodeny as if he were striking a plank with a mallet.”

Aretas A. Saunders (1929) says: “The bird has a variety of calls. One consists of a gurgling note followed by single notes in even time, Ikrak-ika kuh kuh kuh kuh kuh kuh kuh kuh’. Another is a series of groups consisting of two to six notes repeated many times, with one of the notes strongly accented, such as Ikuka kuka kuka or ‘kakukaka kakukaka kakukaka.’ I have known a bird to repeat such phrases over a hundred times without stopping.”

The notes of the black-billed cuckoo are often given on the nest or while the bird is in flight, and they may be heard at all hours of the day or night. Both cuckoos are said to be more noisy just before a rain, hence the name “rain crow.”

Mr. Brewster (1937a) says that “both species coo in the same subdued, mournful, dovelike tones, but when so engaged, the Yellowbill always utters only a single note at a time, and then waits at least a second or two before following it with another precisely similar; whereas the cooing notes of the Black-bill are invariably doubled or trebled or quadrupled, or perhaps even quintupled, yet separated from one another within Such grouping by scarcely appreciable pauses.”

Gerald H. Thayer (1903) has given an interesting account of what he calls “the mid-summer, mid-night, mid-sky gyrations of the Blackbilled Cuckoo, as noted by my father and me for three consecutive seasons in the southwestern corner of New Hampshire”:

Several years before we discovered the nocturnal-fligiit phenomenon, we began to be puzzled by the extreme frequency of Cuckoo calls on summer nights. * * * They uttered both the cow-row notes and the rolling guttural call; but the guttural was much the commoner of the two, except on dark, foggy nights, when the case was usually reversed. * * * The birds were often so far up as to be only faintly audible when directly overhead, with no obstructions interposed; and this on a still night would seem to mean an elevation of at least a hundred and fifty yards. They sometimes flew lower, however, and on cloudy nights often moved about barely above the tree-tops.

* * * On the evening of July 11-a pitch-dark evening with a thundershower lowering,-they were remarkably noisy, both sitting in trees and flying high in air. The seated ones, of which I heard only two, made the Cowcow Dotes, while all the flying ones made the liquid gurgle. I heard this note overhead between thirty and forty times in the course of about three hours, during half of which time I was afoot on the road.

Field marks: This bird may be recognized as a cuckoo by its size, shape, and general coloration. It can be distinguished from the yellow-billed cuckoo by the absence of the distinguishing marks of the latter, the cinnamon-rufous in the wings, and the conspicuously black-and-white lateral tail feathers.

The wings of the black-billed cuckoo are practically uniform in color with its back; and the lateral tail feathers are dark gray, with inconspicuous, gravish-white, smaller tips, bordered inwardly with a dusky spot. The wholly black bill and the red eyelids earl be seen only at short range.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: Southern Canada and the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, south in winter to northwestern South America. Accidental in Italy, the Azores, and Ireland.

Breeding range: The breeding range of the black-billed cuckoo extends north to southern Saskatchewan (Johnstone Lake, Muscow, and Indian Iead) ; southern Manitoba (Carberry, Pottage la Prairie, and Shoal Lake); northern Minnesota (Crooked Lake); southern Ontario (probably Goulais Bay, Toronto, and Stirling); Quebec (Hull, Montreal, probably Quebec, and probably Kamouraska); New Brunswick (Scotch Lake); probably Prince Edward Island (North River); and Nova’Scotia (Wolfville and Pictou). From this point the range extends south along the seaboard to North Carolina (Raleigh and Winston-Salem); Tennessee (Beersheba Springs and Nashville); northwestern Arkansas (Rogers); eastern Kansas (Lawrence and Clearwater) ; Nebraska (Red Cloud, Kearney, and Antioch) ; and southeastern Wyoming (Wheatland). West to eastern Wyoming (Wheatland and Dayton); eastern Montana (Terry); and Saskatchewan (Johnstone Lake).

The species has been detected in summer on several occasions west of its breeding range. Among these are: Colorado (Fort Morgan, Clear Creek, Fort Collins, and Wray); Wyoming (Laramie); Montana (Fort Keogh, Knowlton, and B~illings) ; and western Saskatchewan (Eastend, Skull Creek, Medicine Hat, and Big Stick Lake). On June 23, 1924, a partially completed nest was found near Camrose, Alberta, a range extension that for the time being must be considered unusual (see remarks under “Food”). The species also was recorded at Godbout, Quebec, on August 11, 1885.

Winter range: Available information indicates that in winter this species is concentrated in northwestern South America: Colombia (Antroquia, Medellin, and Bogota) ; Ecuador (Guapulo, La Carolina, Daule, Puna Lake, and Lechugal); and northern Peru (Huamachuco).

Spring migration-Early dates of spring arrival are: FloridaHastings, April 13; Eau Gallie, April 27, Pensacola, May 2. Alaba.ma-Scottsboro, April 18; Barachias, April 22. Georgia-Atlanta, April 24; Athens, April 27. South Carolina-Frogmore, April 24; Spartanburg, April 29. North Carolina-Raleigh, April 15; Piney Creek. May 4. ViroiDia-Blacksburg, April 26: Lynchburg, May 8. District of Columbia-Washington, April 30. Maryland-Baltimore, April 20. Pennsylvaiiia-Jeffersonville, April 30; Ridgway, May 6; Doylestown, May 9. New Jersey-Milltown, May 2; Passaic, May 7. Now York-Medina, May 3; New York City, May 9: Rochester, May 15. Connecticut-Fairdeld, May 1; Hadlyme, ~Iay’ 4; New Haven, May 7. Rhode Island-Block Island, May 6. Massachusetts-Belmont, May 4; Marlboro, May 6; North Amherst, May 12; Danvers, May 12. Vermont-Clarendon, May 12; St. Johnsbury, May 13; Wells River, May 18. New Hampshire-East Westmoreland, N1ay 16; South Hooksett, May 16, Concord, May 21. Maine-South Portland, May 11; Winthrop, May 15; Waterville, May 20. QuebecMontreal, May 10, Hatlev, May 28. New Brunswick-Scotch Lake, May 27. Nova Scotia-Halifax. May 12; Wolfville, May 18. Louisiana-Avery Island, April 12. Mississippi-Bay St. Louis, April 14. Arkansas-Fayetteville, April 30; Broma Towns, May 2. Tennessee-Knoxville, April 12; Tate, April 26. Kentucky-Lexington, May 1, Bowling Green, May 6. Missouri-Jonesburg, May 3; Montgomery City, May 4; Columbia, May 7. Illinois-Rantoul, April 17; Elgin, May 5; 6len Ellyn., May 7. Indiana-Bloomington, April 26; Richmond, April 27; Vincennes, May 7. Ohio-Oberlin, May 1; Columbia, May 2; Upper Sandusky, May 3. MichiganDetroit, May 1; Brant, May 3; Sault,Ste. Marie, May 11. OntarioGuelph, April 19; Ottawa, May 7; London, May 9. Iowa-McGregor, April 24; Mason City, April 30; Wall Lake, May 3. Wisconsin-Racine, May 8; Beloit, May 10; Whitewater, May 11. Minnesota-Montevideo, April 13; Anoka County, May 5; Excelsior, May 13. Oklahoma-Tulsa, May 3: Norman, May 5. Kansas-Fort Leavenworth, May 6; Bendena, May 8; Clearwater, May 9. Nebraska-Valentine, May 1; Red Cloud, May 11; Omaha, May 13. South Dakota-Yankton, May 1; Huron, May 13; Forestburg, May 15. North Dakota–Grafton, April 25; Antler, May 3; Jamestown, May 23. Manitoba-Aweme, May 20; Pilot Mound, May 24; Reaburn, May 26. Saskatchewan-Muscow, May 12; Indian Head, May 20, Fall migration: Late dates of fall departure are: Manitoba-Margaret, September 3; Aweme, September 14. North Dakota-Fargo, September 13; Cando, September 18; Argusville, September 22. South Dakota-Forestburg, September 6; Sioux Falls, September 22; Lennox, October 14. Kansas-Cimarron, September 2; Osawatomie, September 22. Minnesota-Elk River, September 27; Red Wing, October 2. Wisconsin-New London, September 24; Racine, September 24; Madison, September 26. lowa-Wall Lake, September 28; Osage, October 10; McGregor, October 20. Ontario-Ottawa, September 16; Point Pelee, October 18. Michigan-Charity Island, September 20; Grand Rapids, September 26, Detroit, October 9. Ohio-Saybrook, October 1; Berlin Center,.October 12; Columbus, October 15. Indiana-Indianapolis, October 2; Fort Wayne, October 12; Bicknell, October 18. Illinois–Rantoul, October ~; La Grange, October 7; Glen Ellyn, October 21. Missouri-Columbia, October 4; St. Louis, October 16. Kentucky-Danville, October 5; Bowling Green, October 18. Mississippi-Bay St. Louis, October 11. Nova Scotia–Sable Island, September 25. Quebec-Montreal, September 5. Maine-Orono, September 21; Winthrop, October 20. New Hampshire-Jefferson, October 3; Durham, October 5. Vermont-Wells River, September 14; Woodstock, September 18. Massachusetts-West Groton, September 30; North Truro, October 13; Harvard, October 16. Rhode Island-Providence, October 23. Connecticut-New Haven, September 28; East Portland, October 3; Meriden, October 8. New York-Hyde Park, October 6; New York City, October 10. New Jersey-Elizabeth, October 3; Sandy Hook, October 5; Milltown, October 24. Pennsylvania-McKeesport, October 11; Jeffersonville, October 13; Pittsburgh, October 16. District of Columbia-Washington, October 28. Virginia-Naruna, October 18. North Carolina-Chapel Hill, October 3; Raleigh, October 10; Hendersonville, October 12. Georgia-Atlanta, October 14; Thomasville, October 21. Alabama-Autauga County, October 16. FloridaCollege Point, September 28; Pensacola, October 23.

Casual records: While the black-billed cuckoo does not migrate regularly through the Caribbean region it has been recorded on Dominica (September 30, 1904), Tobago, and Trinidad. Gundlach is alleged to have taken a specimen in May (year?) near Cardenas, Cuba, and there is a somewhat doubtful record from the Isle of Pines on May 11, 1909. Specimens were taken in Bermuda in October 1874 and also in April and May 1875. The Ponta Delgada Museum has an undated specimen taken at San Miguel, Ponta Delgada, Azores; a specimen taken in 1858 near Lucca, Italy, is preserved in the Museum of the University of Pisa; and one was taken on September 25, 1871, Killead, County Antrim, Ireland.

Egg dates: Illinois: 13 records, May 7 to July 20; 7 records, June 1 to 26, indicating the height of the season. Massachusetts: 20 records, May 19 to June 20; 10 records, May 30 to Julie 10. Michigan: 14 records, May 25 to September 14; 7 records, June 21 to July 20. 1 New York: 23 records, May 11 to July 18; 12 records, May 29 to Julie 9.