Recently spilt from the Pacific Golden-Plover, the American Golden-Plover is a long-distance migrant that makes extremely long, nonstop flights. During spring migration, American Golden-Plovers move through the central plains states, but during the fall they follow the Atlantic Coast.

American Golden-Plovers can fly at speeds of more than 75 miles per hour. While gregarious during migration, they are very territorial during the breeding season, even showing aggression towards other shorebird species.

On this page

Description of the American Golden-Plover

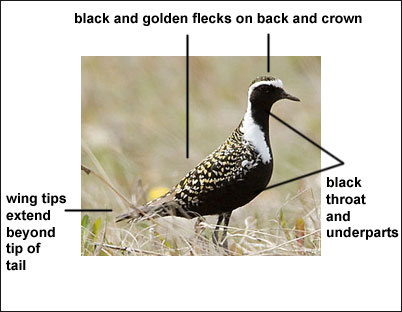

BREEDING MALE

The American Golden-Plover is a large, chunky shorebird with long legs and an upright posture.

– Long white patch on sides of neck.

– Black face, breast, belly, and undertail coverts.

– Much gold or buffy coloration on the upperparts

Female

Much like male:

– Long white patch on sides of neck.

– Mottled with white in the undertail coverts.

– Much gold or buffy coloration on the upperparts

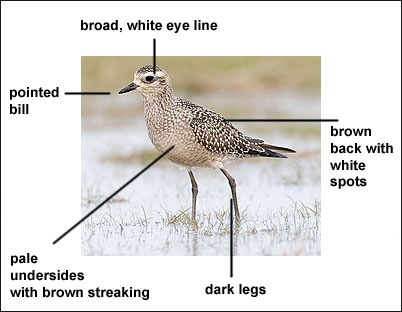

Seasonal change in appearance

Fall and winter birds show much less gold or buffy tones in the upperparts and lack black in the underparts. Instead of a bold white stripe on the neck, only a white eye line is present.

Juvenile

Immatures are similar to fall adults.

Habitat

Grasslands and shorelines.

Diet

Insects, crustaceans, and berries.

Behavior

Forages by running and pecking.

Range

American Golden-Plovers breed in Alaska and northern Canada and winter primarily in South America.

More information:

Bent Life History

Visit the Bent Life History for extensive additional information on the American Golden-Plover.

Wing Shape

The shape of a bird’s wing is often an indication of its habits and behavior. Fast flying birds have long, pointed wings. Soaring birds have long, broad wings. Different songbirds will have a slightly different wing shape. Some species look so much alike (Empidonax flycatchers) that scientists sometimes use the length of specific feathers to confirm a species’ identification.

– wings adult, Washington, Aug

Wing images from the University of Puget Sound, Slater Museum of Natural History

Fun Facts

American Golden-Plovers have an elliptical migration that takes them through the center of the continent in spring, but over the Atlantic Ocean in fall.

The weight of American Golden-Plovers can vary dramatically depending on the time of year and where they are in their annual migration cycle.

Vocalizations

Calls include a variety of repetitive, shrill sounds.

Similar Species

Black-bellied Plover: breeding plumage

The breeding-plumaged Black-bellied Plover has a white crown, white under-tail coverts and lacks the golden-yellow flecks on the back.

Black-bellied Plover: non-breeding plumage

The Black-bellied Plover in non-breeding plumage is generally grayer in appearance and lacks the stronger eye line of the American Golden Plover. Bill of Black-bellied Plover is heavier, wing tip extension shorter.

Pacific Golden-Plover

The Pacific Golden-Plover breeds in northern Alaska and is rarely reported along the west coast. More common in winter in Hawaii. The two species are very similar. The Pacific Golden-Plover has a shorter tail extension, longer legs and bills.

Nesting

The American Golden-Plover’s nest is a depression lined with plant material.

Number: 4.

Color: Buffy with darker markings.

Incubation and fledging:

– Young hatch at about 26-27 days.

– Young fledge (leave the nest) within hours, but associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the American Golden-Plover

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the American Golden-Plover – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

PLUVIALIS DOMINICA DOMINICA (Muller)

The golden plover is not only one of our most beautiful shore birds in its brilliant spring plumage, but its wonderful migration excites our admiration and the comparison of its former abundance with its present scarcity furnishes a striking picture of the ruthless slaughter that has squandered our previous wealth of wild life. A few quotations will serve to illustrate the enormous flights of golden plover that swarmed over both American continents during the past century. Robert B. Roosevelt (1884) thus refers to a flock he saw near Montauk Point, Long Island, many years ago:

A gentle hollow spreads before us for several acres literally covered with the ranks of the much-desired, the matchless golden plover. As they stand in serried legions, the white mark on their heads gi4es a strange checkered weirdness to the phalanx; and we involuntarily pause, spellbound by the novelty of the spectacle. Our host himself, though an old hand, owns that he has never before gazed on such a sight. There they stand, with heads erect and bodies motionless, just out of gunshot. Their number is computed by our companion to be not less than 3,000, closely packed, and apparently awaiting our onset. Warily crawling to within 70 yard~ we halt as we see unmistakable evidences of uneasiness and suspicion among the crowded ranks. They stoop, they run, they rise with “a sounding roar,” to which the united report of our four barrels savagely responds. Away, away with headlong speed scatters and dissolves that multitudinous host, and we hasten to secure our spoils.

Writing of conditions in Argentina about the middle of the last century, W. H. Hudson (1922) writes:

The golden plover was then one of the abundant species. After its arrival in September, the plains in the neighborhood of my home were peopled with immense flocks of this bird. Sometimes in hot summers the streams and marshes would mostly dry up, and the aquatic-bird population, the plover included, would shift their quarters to other districts. During one of these droughty seasons, when my age was 9, there was a marshy ground 2 miles from my home where a few small poois of water still remained, and to this spot the golden plover would resort every day at noon. They would appear in flocks from all quarters, flying to it like starlings in England coming in to some great roosting center on a winter evening. I would then mount my pony and gallop off joyfully to witness the spectacle. Long before coming in sight of them the noise of their voices would he audible, growing louder as I drew near. Coming to the ground, I would pull up my horse and sit gazing with astonishment and delight at the spectacle of that immense multitude of birds, covering an area of 2 or 3 acres, looking less like a vast flock than a floor of birds, in color a rich deep brown, in strong contrast to the pale gray of the dried-up ground all round them. A living, moving floor and a sounding one as well, and the sound, too, was amazing. It was like the sea, hut unlike it in character since it was not deep; it was more like the wind blowing, let us say, on thousands of tight-drawn wires of varying thicknesses, vibrating them to shrill sound, a mass and tangle of 10,000 sounds. But it is indescribable and onimaginable.

Edward H. Forbush (1912) tells of two men who killed plover enough to fill a tip car two-thirds full in one day, during a big storm on Nantucket in the forties. Again he speaks of a great flight which occurred there on August 29, 1863, “when golden plover and Eskimo curlew landed on the island in such numbers as to almost darken the sun. Between seven and eight thousand of these birds were killed on the island and on Tuckernuck.” He says that from 1860 on the species began to decrease, due to the demand created by the failing supply of passenger pigeons, and that in 1890 alone two Boston firms received from the West 40 barrels closely packed with curlew and plover, with 25 dozen curlew and 60 dozen plover to the barrel.

By the end of the last century this species had about reached its lowest ebb; it had become scarce where jt once abounded; no more big flights occurred; and in many places it was rarely seen. But protective measures came in time to save it from extermination; the stopping of the sale of game and the removal of this species from the game-bird list were badly needed. Since the last move was made the species has shown some signs of recovery. Edwin Beaupre (1917) says that “after an absence of almost 15 years, the golden plover has apparently resumed its migratory visits to eastern Ontario.” Prof. William Rowan (1923) says:

This year has been an exceptional golden-plover year. At the place referred to above, somewhere over a thousand birds were seen on the 20th of May alone, in moving flocks varying in number from 30 individuals to several hundreds. This was evidently not unique; for about the same time I got a report from quite another part of the Province that this species was unusual]y abundant, while from yet another quarter I got a very good description of the bird in a letter ~vith a request that I name it for the inquirer, a careful bird observer. Her comment was that she had never seen the species before, but that It was, at the time of writing, present on the plowed fields in enor mous numbers.

And John T. Nichols tells me that “of recent years there has been a distinct increase” on Long Island. If shooting conditions in its winter home could be controlled, its future would be assured.

Spring: From its winter honie on the pampas of Argentina and

Uruguay the golden plover starts early on its long northward migra tion. Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) noted that: The northward migration began with a flock of nine seen January 23, 1921, at a little fresh-water pool on the beach near La Paloma, Uruguay; when flushed these passed on to the west. Single individuals were seen near San Vicente, Uruguay, in flight toward the northwest on January 24 and 30. At Lazeano, Uruguay, birds in passage north were seen in early morning on February 7 and 8, and one was recorded February 15 at Rio Negro, Uruguay. On March 5 at Guamlni, Buenos AIres, 15 came in at dusk to roost on a little mud bar in company with Hudsonian godwits. The migration seemed almost at an end then, as later I saw only four at Tunoyan, Mendoza, on March 23; and on April 5 only a few were heard calling with other shore birds in flight northward over Tucuman, Tucuman.

The exact route followed through the interior of South America is not definitely known, but it is not known to migrate along either coast of that continent. Austin II. Clark (1905) has advanced the theory that it prefers to fly with a beam wind and that it selects the route over which the prevailing winds will produce this condition. He suggests the following as the probable route:

In returning the birds would first go north (across the prevailing westerlies) until in the vicinity of Buenos Aires and the country just to the west of it, where they would encounter northeasterly winds, which would turn them inland, up the valley of the La Plata and along the plains to the east of the Andes, the course gradually becoming more northerly, and then northeasterly in the area covered by the southeast trades. They would reach the Amazon Valley in its western half, and then under the guidance of the northeast trades fly northwest toward the Isthmus of Panama and Central America. The course from here would be northwest across the trades to Texas and the Mississippi Valley. The birds follow up this valley northward and then, on reaching Canada, fly northwest across the prevailing southwesterly and westerly winds to their breeding grounds In western Arctic America.

Another theory advanced by Prof. Wells W. Cooke (1912), into which the facts seem to fit equally well, is that:

Birds follow that route between the winter and summer homes that is the shortest and at the same time furnishes an abundant food supply. The plover seeks the shortest treeless route overland, and alighting on the coast of Texas travels leisurely over the Mississippi Valley prairies, which are abundantly supplied with food, to the plains of the Saskatchewan, and thence to the Arctic coast. Not until Texas is reached can the movements of the golden plover be definitely traced, and at no place between Peru and Texas has It ever been recorded as common. In fact, the records as they stand are what they should be if the plover escapes the forested regions of northern South America and Central America by a single flight of from 2,000 to 2,500 miles from the valleys of eastern Peru to the treeless prairies of Texas.

The golden plover is practically unknown west of the Rocky Mountains in the spring; it has always been a rare straggler on the Atlantic coast at this season; and even as far east as Ohio it rarely occurs. Its main route is through the prairie regions west of the Mississippi River. I have seen what was probably the last of the migration, during the first week of May, along the coastal prairies of Texas, and have watched the late spring flight in Saskatchewan during the last week in May; probably I missed the heaviest part of the flight in both cases. On May 26 to 28, 1917, while driving about Quill Lake, Saskatchewan, I had a good chance to observe a considerable flight of these beautiful birds, all apparently in full spring plumage. The flocks appeared from the southward during the early forenoon, flying swiftly in ever-changing formations, rising to a height of 30 or 40 feet and then sweeping low close to the ground. They all seemed to follow the same course over the burnt-over prairies and the freshly plowed and harrowed lands near the shore of the lake. Occasionally a flock would stop and scatter about to feed; their black bellies and golden-spangled backs were surprisingly inconspicuous on the black ground and among the yellow stubble. They were very shy and restless, constantly on the move, and if followed up too closely they were on the wing again and soon disappeared over the northern horizon. It was almost impossible to approach them on foot when they were on the ground, though a flock would occasionally fly by within gunshot. One that I shot on the ground was 75 paces away, measured distance. Some of the flocks were accompanied by a few buff-breasted sandpipers.

Professor Rowan (1926) says that in Alberta:

The arrival of this species at our lake is precipitate, for there may he none to-day and hundreds to-morrow. The flocks would appear to arrive by night, for they are there at daybreak, when one usually takes the first walk around. They are not birds of the shore line in the spring, but like the buff-breasted sandpiper, they seem nevertheless chiefly to frequent country adjacent to some large lake. This, together with their mode of arrival, in considerable flocks and evidently at night, suggests that they have traveled a considerable distance from their last stopping place. They stay with us some days and then go In the manner In which they came, em mcsse. We have no records earlier than May 8 when the birds may first be expected, but the main contingent arrives nearer the 16th or 17th, while by the 23d or 24th they have usually all gone. Their period with us Is therefore brief as compared with the majority of shore birds.

The remainder of the journey is quickly completed, for, at Point Barrow, John Murdoch (1885) says:

They are among the earlier waders to arrive, as stragglers generally appear about the 20th to the 25th of May, before there Is much bare ground. In 1882 a small party in fall breeding plumage, and apparently all males, arrived May 21, but no more arrived until June 11. The tundra was at this time bare only along the edge of the beach, and the ice and snow was not yet gone from the lagoons. This party remained in nearly the same place for a couple of weeks, feeding on small red worms which they found in marshy spots, and all but two of them were taken, although they were very wild. Along through the first and second week in June they continued to arrive In small parties, and from that time on are quite plenty scattered in pairs and threes all over the tundra. They are very wild and difficult to approach, and very noisy. In addition to their ordinary well-known call note, they have in the breeding season, a loud hut very melodious cry of tudUng! many times repeated, uttered as the bird dies along rather high, with long slow strokes ot the wings.

Nesting: Roderick MacFarlane was very successful in finding nests of golden plover in the Anderson River region and otiler parts of the Arctic barren grounds. He sent a large number of eggs to Washington and I find in his notes references to over 120 nests, on which some data were given, mostly very brief. He says that “golden plover were in great abundance in the barren grounds, as well as along the Arctic coast. They seldom or never nested in the wooded country, though a few specimens were found on the open plains or commons, which occur on the borders of that tract.” Some of the nests on the Arctic coast were “near the beach” or even “within a few yards of the sea water.” The nests were evidently mere hollows in the open tundra, lined with dead leaves; there were no attempts at concealment, but the protective coloring of the eggs made them very difficult to find. He says that “when a nest of this plover is approached the female invariably gets off it at a quick pace, between a run and a walk, which it continues at short intervals until the intruder be attracted to a distance therefrom, when it flies away. The male generally joins its mate in this.” On a few occasions, when surprised, the bird fluttered away for a short distance, but soon began to run as usual. Often the bird left the nest when the men were 100 yards away from it. Once when they had hunted in vain for an hour and a. half,they retired and watched. “After a few minutes she came on at a cautious run, stopping frequently and making occasional excursions in different directions,” and finally settled on the eggs. They found that several of the party had repeatedly passed quite close to, and one had nearly trodden on the eggs. Watching the bird return to the nest, which she generally does within a few minutes, seems to be the best way of finding a nest.

Of the nests found near Point Barrow, Mr. Murdoch (1885) says:

The nest Is exceedingly bard to find, although it Is not concealed at all, bnt Is simply a depression In the bare black clayey tundra lined with a little dry moss. The only vegetation on this part of the tundra is white and grayish moss, which harmonizes so extraordinarily with the peculiar blotching of the eggs that It Is almost impossible to see them unless one knows exactly where to look. A favorite nesting site is on the high banks of the gullies or small streams. No nests were ever found in the grass or in swampy ground.

W. Sprague Brooks (1915) found only one nest near Demarcation Point, Alaska, of which he says:

I found this nest on June 25 with three eggs about one-quarter incubated. The male was on the nest. It took several days to find the nest, for the bird would leave when I was a long way off and begin running about and feeding as though it had nothing else to do. By placing a lump of tundra each day where I first saw the bird I eventuaily found her nest, a mere depression In some greenish moss which, with scattered bits of brown dead vegetation, harmonized extraordinarily with the eggs.

When the bird saw that its nest was finally discovered It showed great distress and ran toward me until about 20 paces distant, where it stood totterlug as If about to fall, with one wing raised over Its back. In a short time the bird, with tail down and a wing dragging, would walk slowly from me. As I never followed, the bird would return and totter a while, repeating the same performance several times until secured for the proper Identification of the eggs.

Eggs: The golden plover’s normal set is of four eggs, but MacFarlane collected many sets of three and one of five. These are quite uniformly ovate pyriform in shape and have only a slight gloss. The ground colors vary from “cinnamon buff” or “light pinkish cinnamon” to “light buff,” “cartridge buff,” or “cream color,” hence more huffy or less olivaceous or grayish than in eggs of the black-bellied plover. They are boldy and profusely marked, more or less irregularly, with large and small spots and irregular blotches of very dark browns or black, “Vandyke brown,” “clove brown,” and brownish black. Sometimes there are a few underlying small spots of “drab gray.” The measurements of 143 eggs in the United States National Museum average 47.5 by 32.5 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 56 by 31, 50 by 34.5, 42 by 34, and 46 by 30 millimeters. Both sexes incubate. The period of incubation for the European species is said to be 27 days.

Plumages: In the downy young golden plover the forehead, crown, back, wings, rump, and thighs are mottled with bright “wax yellow” and black, the yellow being mainly at the tips of the down. A broad patch under the eye, extending back to the ears, and the chin, are white; a spot in front of the eye and an indistinct band above it, the hind neck and the throat are yellowish white, the hind neck being mottled with black; a broad band from the lores to the nape is pale yellow, mottled with black. The remaining under parts are grayish white.

In fresh juvenal plumage, on the breeding grounds, the crown and all the upper parts are brownish black, the feathers tipped or heavily notched with bright yellow, “light cadmium” to “buff-yellow,” brightest on the rump; the wing coverts are pale sepia, notched paler yellow or white; the breast is pale drab, barred, spotted or notched with pale dusky and dull yellow, “mustard yellow” to “Naples yellow”; the belly is white, partially barred with pale dusky; and the tail feathers are sepia, indistinctly barred with darker sepia and tipped with dull yellow. By the time that young birds reach us on migration in September, the bright yellows of the upper parts have faded considerably, and the duller yellow on the breast has disappeared entirely. This plumage is not molted until after the birds leave us; late in the fall, November or later, a partial molt of the body plumage produces the first winter plumage, which can be distinguished from the adult only by the juvenal tail and some retained scapulars and tertials. What happens the next spring we have not the material to show. Most of the birds that we see here in the spring are in fully adult nuptial plumage, but I have seen quite a number of birds, some taken on their breeding grounds, that showed, more or less, old, worn, winter plumage; these may be young birds in their first nuptial plumage.

The postnuptial molt of adults begins with the body molt in August, the new pale drab and whitish feathers of the winter plumage appearing first in the black under parts; this molt continues through September while the birds are migrating. But the primaries are not molted until winter, November to February. In winter the plumage of the under parts is very pale drab, shading off to almost pure white on the chin and belly; the adult tail is irregularly barred with dusky and grayish or yellowish white; the feathers of the mantle are brownish black, narrowly edged with yellow, not notched or spotted as in spring. The prenuptial molt of the body plumage begins in March and lasts until May in ~some individuals; many old winter feathers are often found in breeding birds, especially in the wing coverts, scapulars, tertials and back. The beautiful nuptial plumage is too well known to need description here.

Food: The favorite feeding grounds of the golden plover are rolling pasture lands where the grass is short or scanty, prairies, plains, plowed lands and occasionally open sand or mud flats. Its food consists almost entirely of insects, chiefly Orthoptera which abound in the pasture lands. It is said to feed mainly on grasshoppers, but George H. Mackay (1891), who is very familiar with it, says that he has never seen it eat any, though he has watched it through a strong glass near at hand. He says:

I have also examined the stomachs of a good many which I have shot on Nantucket, and have never found any grasshoppers In them, nor in fact anything but crickets (which seem their principal food there), grass seeds, a little vegetahie matter, like seaweed, coarse sand, and small stones. I have also frequently shot them with the vent stained purple, probably from the berries of the Empetrum nigrum.

They must find abundant food in the north, for they are always very fat when they arrive here. The large numbers of grasshoppers, locusts, crickets, and other insects that they destroy make them very beneficial birds to the farmers of the west, where they also do much good by eating the grubs, cutworms, and wireworms on freshly plowed lands, their favorite resorts in spring. On the shores and open flats they find some small mollusks and crustaceans. The crops of two which Lucien M. Turner collected in northern Ungava were filled with ripening berries of Enipetrum nigrum and remains of spiders. Hantzsch found them eating beetles and caterpillars on Baffin Island.

Behavior: The flight of the golden plover is exceedingly swift, strong and protracted, as it must be to make such wonderful migrations. Over the prairies the flocks sweep along in compact and ever changing formations, skimming close to the ground at times and then rising high in the air, frequently whistling as they go. William Brewster (1925) has described their flight, as seen at Umbagog Lake, Maine, as follows:

They habitually flew faster than any of the other waders and perhaps more swiftly than any of the ducks except the hooded merganser. Their long, pointed wings, lifting high and cutting deep at each stroke, beat, rapidly and ceaselessly, yet so easily and smoothly as to indicate comparatively slight muscular effort. If they happened to pass near at hand or overhead their flight was likely to Impress one as having not only exceeding speed hut Irresistible momentum, also as of solid projectiles, hurtling through the air. Seen at a distance they appear to be moving more slowly and looked not. unlike passenger pigeons.

When preparing to alight the flocks often perform extensive evolutions, circling and turning, as they sweep about over the ground, as if selecting a satisfactory landing place. When a suitable spot is chosen, they all alight in a compact bunch, raising their wings high above their backs before folding them, and soon scatter over the ground to feed. When on the ground they are very active, running rapidly and gracefully, stopping suddenly to look around, with head held high, and then striking quickly at some morsel of food. Mr. Mackay (1891) says:

When scattered over considerable ground, as is usual after they have been any length of time on their feeding ground, every bird apparently on Its own hook, if alarmed, a note is sounded; they then rise so as to meet as soon as possible at a common center, which gained, away they go in a compact body. During the middle of the dny they are fond of seeking the margins of ponds, where they sit quietly for a long time, If undisturbed. When disturbed they are almost certain to return, In a short time, to the same spot from which they have been started, that Is, if they have been resting or feeding there any length of time. When suspicious, it is very difficult to approach, decoy, or call them; if not harassed, they are as a rule quite tame and gentle, and can be easily driven up to with horse and wagon.

Voice: 4ohn T. Nichols says in his notes:

The flight note of the golden plover In migration is a far-reaching que-e-e-a, with a qunver in the middle and falling at the end. Though with a thrilling plover quality it at the same time has an affinity to the kilideer’s cry, being less mellow and whistled than the note of the hlackbelly, which It also suggests, reversed.

Mr. Mackay (1891) says that when these birds are approaching decoys every bird seems to be whistling “a note like coodle, coodle, coodle.” Mr. Forbush (1912) calls its note “a plaintive toc-lee-e,” or “a bright whistle, queep-quee-lee-leep.” Others have given different renderings of some of the above notes.

Field marks: The bird with which the golden plover is most likely to be confused is the black-bellied plover, but the golden is a smaller, more slender, bird, with a generally darker appearance. When seen in flight the tone of the tail is very dark and the axillars, under the wings, are grey, whereas in the black-bellied the tail is decidedly whitish and the axillars are very conspicuously black in all plumages; furthermore the black-bellied has a conspicuous light wing bar, which is lacking in the golden. The notes of the two are quite different. When in hand the golden is seen to have no hind toe. Mr. Nichols suggests that the golden has a swifter, more buoyant flight, suggestive of the killdeer.

Fall: Mr. Murdoch (1885) refers to the beginning of the migration as follows:

The nesting season continues till the first or middle of July, about which time the adults begin to collect in flocks, feeding together around the ponds on the higher tundra, associated sometimes with a few knots or a struggling curlew. The old birds leave for the south about the end of July, and no more plovers are to be seen until about the middle of August, when the young, who heretofore have been keeping out of sight, scattered over the tundra, gather into flocks, and for several days are quite plenty on the dryer hills and banks, after which they depart. Stragglers may be seen up to the end of August.

The main trend of the fall migration is southeastwards, mainly west and south of Hudson Bay, but perhaps across it also, to the Atlantic coast, mostly north of New England. In favorable weather the flight is over the ocean from Nova Scotia to South America over, or to the eastward of, Bermuda, and the Lesser Antilles. Mr. Clark (1905) figures out that this is the course they would take, if they flew with a beam wind, across the prevailing winds. Of thek course after landing in British Guiana, he says:

From this point their course is not accurately known; but if we apply this theory, they would follow down the northeastern tributaries of the Amazons until they came within the influence of the southeast trades, which would carry them sonthwest, over central Aniazonia toward Peru and Boliva. Somewhat northwest of the Matto Grosso region, the birds would come under the influence of the easterly winds on the southern border of the trades, which would turn them south, and gradually (as they became more northeasterly) southeast, which would bring the plover into tile prairie region of the Argentine. Here the prevailing westerlies of the pampas region would be felt, and the birds would, under their influence, continue down ‘the eastern part of Fatagonia toward Tierra del Fuego.

To add strength to his theory he says that there are specimens in the British Museum from Mount Roraima and the Maroni River, Surinam, and from Peru taken in September and October.

Some birds on the f all migration wander as far north and east as Baffin Island and northeastern Labrador. Lucien M. Turner refers in his notes to several adults which he saw and two which he collected, near the mouth of the Koksoak River, between July 24 and August 19, 1882; and I have a specimen in my collection taken near Hopedale, Labrador, a young bird. flantzsch found this plover breeding on Baffin Island.

Edwin Beaupre (1917) writes:

In September, 1906, a great flight of plover passed over the city of Kingston, which is located on the extreme eastern end of Lake Ontario. The flight was first noticed about 8 o’clock in the evening, and to one familiar with the soft, sweet piping of the golden plover, there was no difficulty whatever in recognizing the bird. A record of the flight showed that eight flecks passed ever the city, flying very low, at intervals of about 10 minutes. Toward midnight it was Impossible to enumerate the flocks, the flight being continuous. This must have been the main migration for that year, and it continued until 4 o’clock in the morning, covering eight hours. Allowing a speed of 25 miles an hour: a conservative estimate: the distance between the leading flocks and the rear guard must have been approximately 200 miles. What a sublime spectacle this would have been had one the privilege of seeing it in the open light of day! The vanguard of this great aerial aggregation must have reached almost to the Atlantic seaboard, while the rear flocks were trailing their wonderful way over the eastern waters of Lake Ontario. They no doubt began Their ocean journey some miles south of the coast of Nova Scotia, hut not far enough to seriously affect their regular route to Argentina, in which country they escape the hardship of a Canadian winter.

The above quotation and the fact that William Brewster (1925) recorded the golden plover as visiting the Umbagog Lake region in Maine “regularly and rather plentifully not so many years ago,’~ suggests the idea that some of the birds we used to see in New England came by an overland route. However, our big flights were probably birds that came in from the sea under stress of bad weather, either before or during easterly storms accompanied by heavy rains or thick fog. According to Mr. Mackay’s (1891) records, covering a period of 32 years from 18.~8 to 1890, the last week in August seems to be the best time to look for a flight, though he says “it is unusual to see any but scattering birds before the 10th of September.” My earliest record for adult birds is August 9; practically all the birds which come in August are adults. The young birds come in September; my latest date is October 7. The appearance of either adults or young on our coast has always been very uncertain and irregular, dependent on the necessary weather conditions coming at the proper time.

Mr. Mackay (1891) says:

While I have continually shot the young birds oa Nantucket, and in ether parts of Massachusetts, their arrival is a much more uncertain event than that of the older birds, there being some years when I have seen none, and others only a few. I have never known a year when they were anything like as numerous as I have seen the older birds.

During some years large flocks of golden plover pass over the Bermudas in September and October, according to Capt. Savile G. Reid (1884), “but, unless in stormy weather, they do not alight in any great numbers. Numbers appeared in September, 1874, frequenting the grassy slopes of the north shore: their favorite haunt: and even the parade grounds, during the continuance of a three day’s revolving gale.”

Col. H. W. Feilden (1889) writing of conditions in Barbados, the easterumost of the West Indies, says:

Stragglers arrive as early as July and the beginning of August, but the main flights come with the first heavy weather after the 27th of August, and long experience and observation proves that this date is kept year after year with wonderful accuracy. The course of all the migratory Charadrildae across Barbados In the autumn Is from the northwest to southeast, and if the wind blows from southeast the birds are brought down to the island, for it appears to be a tolerably well established observation that birds prefer migrating with a “beam” wind. A shift of wind from the northeast, with squally weather to the southeast, is ardently longed for by the Barbados sportsmen toward the end of August, as this forces the migratory hosts to alight Instead of passing over at a great height, as they are seen to do when the wind is from the northeast. The first arrivals of this species are invariably black-breasted birds, showing that the old birds precede the young, and the first corners are nearly all males. The young birds without black on the breast appear about the 12th of September, and continue to pass till the end of October, sometimes stragglers are as late as November. Even In the most favorable seasons, only a fraction of the immense flights that pass over the island ever alight.

Much has been written about The Atlantic flight of the golden plover and remarkably little has been said about the southward flight in the interior, but such a flight occurs regularly, though in much smaller numbers. Professor Rowan (1926) says that in Alberta:

We have notes of hundreas going south in a single day In mid September, when the main movements occur annually. An Interesting feature of the fall migration of golden plover Is that it consists entirely of young birds. The earliest record we have is August 18 and the next August 24. These are rather early, September being the chief month of arrival. The fall movements are protracted, and we may have small flocks with us till toward the end of October. Another feature of the autumn migration Is a change of habit. The birds, while often noted on pasture (particularly if In large flocks) more usually frequent the muds and behave ilke the majority of other waders. They associate freely and habitually with other species. They behave like the strays of the spring. Being birds of the year there is no doubt in their case that they are sexually undeveloped. We have a single record of an adult bird in the fall collected by Harrold on August 22. It was noted the previous day, but not secured, and proved to be a female well advanced In its moult. There Is one other reliable autumn record for an adult golden plover from the Province, seen at Sullivan Lake in July by Mr. T. E. Randall. Until we have spent the whole of July at our lake or some other suitable observation station, it will be impossible to say that adults never: except accidentally as strays: come south through the Province, but all evidence available Indicates that they do not do so.

I can not wholly agree with Professor Rowan’s evident belief that all the birds that migrate through the interior are young birds and that very few young birds take the Atlantic route. However, the dates given by numerous observers in the Mississippi Valley and in Texas would seem to indicate that they were nearly all referable to young birds, as they are generally late dates. The main migration route for both adults and young is evidently the Atlantic route; the species is comparatively rare in the interior, south of Canada. It is still rarer on its southward migration along the Pacific coast; the dates are mostly late, probably for young birds; D. E. Brown has sent me two records from Washington. October 7, 1917, Gray’s Harbor County, and November 14, 1915, Clallam County. Apparently most of the adults take the Atlantic route; the young birds are spread out over the whole country, but are much more inclined to t.he eastern route.

Game: The golden plover has been a famous game bird. It was a most desirable table bird, as it was usually very fat and its flesh had a delicious flavor on account of its clean, upland feeding habits. The uncertainty of its appearance and its enormous numbers at favorable times made its pursuit most interesting. During the years of its abundance it was slaughtered in almost incredible numbers. Audubon (1840) writes:

While at New Orleans, on the 16th of March, 1821, I was invited by some French gunners to accompany them to the neighborhood of Lake St. John to witness the passage of thousands of these birds, which were coming from the northeast and continuing their course. At the first appearance of the birds early in the morning, the gunners had assembled in parties of from 20 to 50 at different places, where they knew from experIence that the plovers would pass. There stationed, at nearly equal distances from each other, they were sitting on the ground. When a flock approached, every individual whistled in imitation of the plover’s call note, on which the birds descended, wheeled, and, passing within 40 or 50 yards, ran the gauntlet, as it were. Every gun went off in succession, and with such effect that I several times saw a flock of a hundred or more reduced to a miserable remnant of five or six Individuals. The game was brought up after each volley by the dogs, while their masters were charging their pieces anew. This sport was continued all day, and at sunset, when I left one of these lines of gunners, they seemed as intent on killing more as they were when I arrived. A man near the place where I was seated had killed 63 dozens. I calculated the number in the field at 200, and supposing each to have shot 20 dozen, 48000 golden plovers would have fallen that day.

John C. Cahoon (1888) describes a method of shooting golden plover employed by old gunners on Cape Cod, as follows:

Several weeks before the ilme for the flights to occur, they go to an old field or pasture that they know the birds usually come Into and burn off the old grass and bushes for quite a space. Thea a hole is dug large enough for one or two persons to sit In comfortably, with only the top of their heads above the surface. In a few weeks the grass springs up and the green patch Is easily distinguished from its duller surroundings by the plover flying about, and they are sure to come to this place. The gunner, with his decoys out, sits in his pit with only the top of his head out, which is covered with a green cap. A flock, before alighting to the decoys, will usually circle about several times, often flying directly over the gunner’s head only a few yards away. An experienced gunner will not shoot when they are so near and scattered, as he could kill hut one or two, but will wait for them to bunch at the right distance, which they are sure to do while turning, and seize that opportuntty to fire, killing many at one shot.

Mr. Mackay (1891) says: “They arc extremely gregarious, and I have had the same flock retllrn to my decoys as many a~ four times after some of their number had been shot each time.” This remark probably refers to adult birds, which come readily to decoys or in response to skillful whistling; I have seen a single bird whistled up from so far away that it was hardly visible. Professor Rowan (1926) says that he has “found it practically impossible to whistle them within gun range.” He probably refers to young birds, of which Mr. Mackay (1891) writes:

These young birds invariably appear wild and wary, much more so than the old ones. They are also very erratic in their movements and flight when with us. They usually will not pay so much attention to the decoys or call whistle as do the old birds; and I have seen them, when very shy and after being disturbed, mount up into the air and nearly turn over on their backs whiie flying with great velocity. It is a noteworthy fact that when a flock of these young biAs is apprc.achiiig no dependence can he placed on their movements. They may sometimes sweep down within a few yards of the sportsman, passing with great rapidity over his head, all scattered; or down close to the stand and then up into the air; or they may turn suddenly. My experience has taught me not to wait, as Is my custom with the older birds, to get them together before shooting, but fire at them whenever and wherever I can if they are within range. The older birds rarely indulge in any similar antics.

During the days of spring shooting in the west golden plover were often shot, without decoys, by making a blind or selecting some natural hiding place within their regular fly ways, which were generally quite well established and known. It was always difficult to stalk them on foot, but where there were no fences they could be stalked successfully by a hunter on horseback or in a wagon.

Winter: The golden plover arrive in their winter home early in September, or rarely late in August, where they remain until February or March. W. H. Hudson (1920) writing of the days when these birds were plentiful, says:

The American golden plover is abundant and well known to every one by its native name, Chorlo, throughout southern Argentina. Its wild, clear notes are first heard about the last week in August, and among the first comers many individuals are seen still wearing the nuptial dress. After their long journey from the Arctic regions they are lean and not worth shooting; two months later they become excessively fat, and are then much appreciated by gourmets. But although so regular in their arrival, they do not re~’ularly visit the same localities every season; the bird may he abundant in a place one year and scarce or absent altogether the next. During the spring, from September to December, they prefer open plains with short grass and In the neighborhood of wet or marshy ground; at the end of December, when the giant thistle (Cerdaas muriana), which often covers large areas of country, has been burnt up by the sun and blown to the ground, they scatter about a great deal in flocks of from one to four or five hundred. At noon, however, they all resort to a lagoon or marshy place containing water, congregating day after day In such numbers that they blacken the ground over an area of several acres in extent, and at a distance of a quarter of a mile the din of their united voices resembles the roar of a cataract. As population increases on the pampas these stupendous gatherings are becoming more and more rare. Twenty-five years ago it was an exceptional thing for a man to possess a gun, or to use one when he had it; and if Chorlos were wanted a gaucho boy with a string a yard long with a ball of lead attached to each end could knock down as many as he liked. I have killed them in this way myself, also with the bola perdida: a ball at the end of a long string thrown at random into a cloud of birds.

Doctor Wetmore (1926) saw golden plover on migration in Paraguay during September; they “came to the open shores of lagoons with other sandpipers, but were more often seen in flocks of 30 or 40 scattered over open savannas where the grass was not too long.” He saw them also in Argentina during November and December, where they seemed “to be restricted during the resting period to the better watered grass-grown eastern pampa.”

Again (1927) he says:

The golden plover in the south has been most common on open plains, but ranges to some extent on the mud flats of the coast. It is in this last area that the species may he expected to survive as the pampas become more closely occupied by man. These buds are hunted extensively and So many have heen killed both in the north and south that their numbers have been greatly reduced. Though recorded in its nesting rouge as only fairly common at hest, the region where the golden plover is found at this season Is extensive, so that the number of birds in existence Is still considerable. Careful watch should be kept on its abundance.

DISTRIBUTION

Range: North and South America, accidential in Europe.

Breeding ran ge.: The breeding range of the American golden plover has not been defiuiitely separated from that of its western relative (Plwvialis d. fulva). It has, however, been found that in Alaska fulva is more nearly confined to the northwestern coastal regions, while dontinica is in the interior and on the northern coast.

The breeding range may be defined as extending north to Alaska (Point Barrow, Collison Point, and Demarcation Point); Baflin Island (Kangianga, Tikerakdjuak, and Kangidli); and Franklin (Walker Bay, Bay of Mercy, Winter Harbor, Wellington Channel, and probably Igloolik). East to Baflin Island; Franklin (probably Igloolik and Winter Island); and northeastern Keewatin (Whale Point). South to Keewatin (Whale Point); Mackenzie (Casba River, Lac de Gras, Bernard Harbor, Rendezvous Lake, Fort Anderson, and Fort McPherson); and Alaska (Gens de Large Mountains, Beaver Mountains, and probably Nushagak). West to Alaska (probably Nushagak and Point Barrow).

It also has been detected in summer in Greenland (Jacobshaven and Godthaab), but there is no evidence of breeding in that region.

Winter range: The winter range of the American golden plover extends north to rarely Chile (Arica) ; and rarely Brazil (Villa Maria, Matto Grosso, and Rio de Janeiro). East to rarely Brazil (Rio de Janeiro and Santa Catharina) ; Uruguay (Montevideo) and Argentina (La Plata, Cape San Antonio, and Bahia Blanca). South to Argentina (Bahia Blanca, Sierra de la Ventana, Carhue, and Mendoza). West to western Atgentina (Mendoza) ; and rarely Chile (Arica). On rare occasions individuals may pass the winter season at more northern points as Nauta, Peru (Sharpe), and Old Harbor, Costa Rica (Carriker). Winter occurrences at other northem localities probably refer to crippled birds or erroneous identifications.

Migration: The main migration route of the American golden plover is of an elliptical nature. In late summer, after the breeding season, the birds move southeast across northern Canada to the coasts of Labrador and Nova Scotia, from which points they fly, apparently without stopping, to the northeast coast of South America, passing thence through the interior to the pampas region of Argentina. The northward flight in spring is made farther west, through Ceneral America, up the Mississippi Valley to the prairie Provinces of Canada.

Individuals and small flocks are, of course, noted more or less regularly in both spring and fall, both on the Atlantic coast and in the interior, but the main route should be borne in mind when considering the following dates of arrival and departure.

Spring migration: Early dates of arrival in the spring are: Porto Rico, Mameyes, February 16; Bermuda, March 9, 1852 (only spring record); New York, Long Island City, April 17, and Fair Haven Light, May 3; Massachusetts, Revere, March 6, and Somerville, March 20; Nova Scotia, Pictou, May 17; Quebec, Godhout, May 31; Franklin, Igloolik, June 14; Louisiana, New Orleans, March 16, Avery Island, March 28; and West Baton Rouge, April 2; Arkansas, Fayetteville, March 20; Missouri, St. Louis, March 23, Kansas City, April 11, and Kings Lake, April 12; Illinois, Mount Carmel, March 12, Lebanon, March 17, and Chicago, March 22; Indiana, Terre Haute, March 22, Greencastle, March 28, and Muncie, March 30; Ohio, Sandusky, March 26, West Liberty, April 2, and Columbus, April 4; Michigan, Pittsfield, April 20; Iowa, Scranton, March 25, Newton, March 27, and Keokuk, April 14; Wisconsin, Clinton, April 9, and Racine, April 14; Minnesota, Heron Lake, April 12, Waseca, April 21, and Wilder, April 24; Texas, Gainesville, March 7, Mont Belvieu, March 8, Boerne, March 9, and Indianola, March 15; Oklahoma, Caddo, March 11; Kansas, Richmond, March 22, Lawrence, March 29, Manhattan, April 4, and Emporia, April 18; Nebraska, Kearney, April 8; South Dakota, Fort Sisseton, April 13, Huron, April 25, and White, April 26; North Dakota, Larimore, May 2, and Grafton, May 3; Manitoba, Aweme, April 23, Treesbank, May 1, Portage la Prairie, May 8, and Margaret, May 8; Saskatchewan, Osler, May 8, and Indian Head, May 9; Mackenzie, Fort Simpson, May 15, and Fort Resolution, May 23; Alberta, Alliance, May 5, Mundare, May 12, Camrose, May 7, and Red Deer, May 9; and Alaska, Beaver Mountains, April 29, Sitka, May 5, Flat, May 11, Fort Reliance, May 13, Fairbanks, May 17, and Point Barrow, May 21.

Late dates of spring departure are: Argentina, Rio Negro, February 18, Mendoza, March 23, and Tucuman, April 5; Guatemala, Duenas, April 12; Louisiana, Avery Island, May 3, and Breton Island, May 13; Kentucky, Crab Orchard, May 10; Missouri. Hunnewell, May 18, and Boonville, May 31; Illinois, Addison, May 10, Rantoul, May 12, and Chicago, May 17; Indiana, Lebanon, May 23; and Michigan City, June 2; Ohio, Sandusky, May 19, Bay Point, May 23, and Wauseon, May 27; Iowa, Gilbert Station, May 16, Cedar Rapids, May 17, and Clear Lake, May 20; Wisconsin, Racine, May 4, and Madison, May 30; Minnesota, Hallock, May 20, Wilder, May 22, and Twin Valley, May 30; Texas, Corpus Christi, April 28, Gainesville, May 12, and Point Isabel, May 15; Kansas, Manhattan, May 4, Paola, May 7, and Lawrence, May 8; Nebraska, Valentine, May 25; South Dakota, Sioux Falls, May 23, White, May 25, and Harrison, May 27; North Dakota, Devils Lake, May 23, Jerusalem, June 1, and Larimore, June 7; Manitoba, Aweine, May 29, Margaret, June 3, and Shoal Lake, June 6; Saskatchewan, Indian Head, May 22, Winston, May 29, and Churchill River, June 2; Colorado, Denver, May 17; Alberta, Mundare, May 26, Sedgewick, May 30, and Fort Chipewyan, June 1; and British Columbia, between Shusicap Falls and Mabel Lake, May 29 (only spring record).

Fall Migration: Early dates of arrival in the fall are: British Columbia, Graham Island, July 27, Sumas Lake, August 19, and Chilliwack, August 26; Keewatin, Cape Eskimo, August 4; Manitoba, Aweme, August 6, Shoal Lake, August 21, and Margaret, August 27; North Dakota, Fort Berthold, September16; South Dakota, White, September 12, great bend of the Missouri River, September 18, and Harrison, September 20; Nebraska, Nebraska City, August 3, and Ames, August 22; Minnesota, St. Vincent, August 29, and Hibbing, September 13; Ontario, Toronto, August 25, and Brighton, August28; Michigan, Houghton, September 5, Charity Island, September 9, and Detroit, September 10; Ohio, Columbus, August 23, New Bremen, September 1, Youngstown, September 2, and Cleveland, September 8; Indiana, Waterloo, August 25, and Lebanon, September 29; Illinois, Rantoul, August 6, Glen Ellyn, September 10, and Chicago, Septeinber 13; Louisiana, mouth of Mermentau River, August 11; Mississippi, Bay St. Louis, September 26; Newfoundland, St. George Bay, August 17; Quebec, Gaspe Peninsula, August 29, and Montreal, August 31; Prince Edward Island, Malpeque, August 23; New Brunswick, Scotch Lake, August 21; Nova Scotia, Sable Island, August 20; Maine, Portland, August 12; Massachusetts, Ipswich, July 18, Plymouth, August 7, Nantucket, August 12, Cape Cod, August 15, and Monomoy Island, August 18; Rhode Island, Newport, August 12, and Kingston, August 19; Connecticut, Bridgeport, August 14, and Guilford, August 27; Rhode Island, Point Judith, August 21; New York, Montauk Light Station, August 9, Long Island City, August 12, Syracuse, August 22, and Shinnecock Bay, August 29; New Jersey, Great Bay, July 19; Cuba, Guantanamo, September 30; Lesser Antilles, Barbados, July 24, Grenada, August 24, St. Croix, August 31, and Sombrero, September 2; British Guiana, Auni, August 30; and Paraguay, Puerto Pinasco, September 6. Specimens also have been detected at Bermuda as early as July 25 (Hamilton).

Late dates of departure in the autumn are: Alaska, Nome, Septeinber 14, Baranof Island, September 18, Kenai River, October 7, and St. George Island, October 18 (there is a strong possibility that all of these Alaskan records refer to the Pacific form, Pluvialis d. fulva); British Columbia, East Kootenay, October 13, Chilliwack, October 14, and Comox, November 4; Alberta, Edmonton, September 23, delta of the Athabaska River, October 10, and Beaverhill Lake, October 22; Montana, Terry, September 23, and St. Marys Lake, October 1; Wyoming, Rock Creek, October 25; Colorado, Newcastle, October 5; Mackenzie, Manito Islands, September 14, Lower Slave River, September 29, and Fort Liard, October 5; Saskatchewan, Indian Head, October 2, and Quill Lake, October 11; Manitoba, Aweme, October 16; South Dakota, Fort Pierre, October 21, and Fort Sisseton, October 26; Nebraska, Lincoln, November 14; Kansas, Emporia, October 22, and Lawrence, October 23; Minnesota, Madison, October 22, St. Vincent, October 26, and Lanesboro, November 2; Iowa, Bronson, November 9, and Keokuk, November 9; Ontario, Toronto, October 23, Brighton, November 3, and Ottawa, November 4; Michigan, Gibralter, October 12, Mainstee, October 17, and Detroit, November 4; Ohio, New Bremen, October 23, Painesville, October 31, and Youngstown, November 11; Indiana, English Lake, November 15; Illinois, Morgan Park, October 28, Hinsdale, November 4, and Urbana, November 8; Arkansas, Crocketts Bluff, October 22; Greenland, August 7; Franklin, Baffin Bay, September 3; Quebec, Koksoak River, September 19, Kamouraska, October 19, Montreal, November 8, and Quebec City, November 10; Nova Scotia, Sable Island, October 22, and St. Marys Bay, October 23; Maine, Lewiston, October 16, and Portland, November 15; Vermont, Wells River, October 14; Massachusetts, Monomoy Island, October 13, Plymouth, October 24, and Provincetown, November 19; Rhode Island, South Auburn, October 12, and Newport, October 24; Connecticut, West Haven, October 25, and Hartford, October 24; New York, Ithaca, October 29, Rockaway, October 30, Orient Point, November 5, and Auburn, November 8; Bahamas, Cay Lobos, October 25; Porto Rico, Anegado Lagoon, November 4; West Indies, Barbados, December 7~ and Costa Rica, San Jose, December 15.

Casual records: South of New Jersey on the Atlantic coast, this species has been recorded on a few occasions, among which are: District of Columbia, Washington, one about 1860; Virginia, Smiths Isla:nd, September 28, 1897, and Wallops Island, several occurrences between August 12 and October 3 (Warren) ; North Carolina, several records in spring between April 15 (Waterlily), and May 10 (Currituck), and in fall between August 29 (Martins Point), and September 29 (Churchs Island); South Carolina, Chester County, September 19, 1877, Christ Church Parish, November 27, 1912, and Charleston, November 4, 1911, and December, 1880; and Florida, Miakka, November 19, 1901, and December, 1900.

On the Pacific coast of the United States it is only casual: Washington, several records in the fall between September 9 (Port Townsend), and November 14 (Dungeness) ; Oregon, Netarts Bay, September 7, 1912; and California, Playa del Rey Lagoon, October 4, 1923, Santa Cruz, October 22, 1888, and possible at Coronado, January 12: 20, 1908 (Torrey). Suckley reported it from the vicinity of San Francisco, and Kobbe from Menlo Park and Vallejo, but both of these records are indefinite.

The American golden plover has been obtained a few times in Great Britain, Essex, August, 1896, Perthshire, August, 1883, Leadenhall Market, fall of 1882, and Mayo County, September, 1894; while a single specimen was taken on Heligoland, December 20, 1847.

Egg Dates: Arctic coasts of Alaska and Canada: 176 records, June 1 to July’15; 88 records, June25 to July 2.